Abstract

Interactions with classroom friends may be an important contributor to first and second language development, but to date this hypothesis has not been tested. Using a longitudinal design, the current study investigated the relationship between classroom friendships and oral language development in children. In 8 classrooms, we assessed the relationship between oral language skills and classroom social networks. Across the classrooms, 165 primary school children in Austria (83 boys; 119 L2 learners; age: 6–10) were assessed on oral language proficiency at the beginning of the school year (T1) and 6–7 months later (T2). Results indicated that the more reciprocal best friendships at T1, the greater language improvement at T2. Language improvement was strongest among friends with moderate differences in language proficiency, regardless of whether students were first or second language learners. These results underline the importance of positive social relations at school for language learning broadly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Promoting students’ language skills means providing them with opportunities to apply and learn the language used in school (Carhill-Poza, 2017). Various studies have shown that classrooms facilitate language-rich interactions not only between teachers and children but also between multilingual peers (e.g., Atkins-Burnett et al., 2017; Aukrust et al., 2011; Blum-Kulka & Gorbatt, 2014; Grøver et al., 2018). Peers play an essential role in language learning (Carhill-Poza, 2017) especially for bilingual learners. Bilingual learners must acquire linguistic communication skills in addition to academic language skills (Karem & Hobek, 2022). The relationship between different types of friendships (e.g., friend vs. best friend) and children’s language development in elementary school has been little studied despite evidence showing that peer relationships provide more opportunities for verbal interactions (Miell & MacDonalds, 2000; Rubin et al., 2008) and support the use of advanced language (Carhill-Poza, 2017; Pellegrini et al., 1997).

The present article aims to address this gap. Using a longitudinal design, we examined the relationship between peer friendship type (friend and best friend) and oral language development. Our study examined multilingual elementary classes that included children who spoke the language of school (German) as their primary language (L1 learners) as well as children who spoke German as their secondary language (L2 learners).

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 A sociocultural theory of interaction

According to sociocultural theories, language learning is a process in which learners use language in collaborative dialogue and jointly construct language or knowledge about language (Swain et al., 2002). Therefore, the use of language and participation in “socially-constructed, meaningful activities and interactions” (Erdemir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020, p. 7) is a fundamental source for the development of children’s first and second language (Erdemir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020; Ellis, 2012; Philp et al., 2008). Joint activities can take the form of adult-child (Donnelly & Kidd, 2021) or teacher-student interaction (Gibbons, 2005; Schwartz & Gorbatt, 2017), where adults or teachers act as ‘experts’ and scaffold the child’s or learner’s (i.e., novices) language learning processes by using language mediation strategies (e.g., corrective feedback or modeling; Blum-Kulka & Snow, 2004; Swain et al., 2002). Through language mediation, an ‘expert’ aligns their language use to the ‘novice’s’ zone of proximal development (ZPD), which describes the distance between what a learner can achieve unaided and what the learner can do under the guidance of or in collaboration with an expert (Vygotsky, 1978).

Recent studies focus increasingly on peer-peer interactions in which peers concurrently act in the role of ‘expert’ and ‘novice’, supporting each other’s language development by aligning to the ZPD (Blum & Kulka, 2004; Erdermir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020). While adult’s or teacher’s language mediation is intended, language mediation provided by more competent peers (i.e., L1-speaking, or advanced L2 learners) tends to be incidental (Erdemir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020).

However, little is known about whether both sides of the peer-peer dyad benefit from the transaction of language (e.g., learning, teaching). This question is particularly important to peer interaction in primary school. At this age, children are still developing cognitively, including language skills. Their role as ‘experts’ or ‘novices’ is in a transitional stage, therefore, less clearly and less permanently distributed. It can be assumed that both roles benefit from the interaction. Studies with kindergarten children show strategies used by competent peers support the vocabulary development of less competent peers by “labeling an object, labeling an action, demonstration and extending” (Erdemir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020, p. 23). Thus, it can be assumed that competent peers broaden their language experiences by performing speech acts, such as “to define” or “to explain,” that are not common at their age. In the current study, we indirectly examine this peer-to-peer interaction by investigating the language development of children participating in these interactions and assume that language-rich interactions with peers, such as classmates, provide children with the opportunity to use language, and should thus, contribute to first and second language development.

2.2 Classroom peers and oral language development

In line with sociocultural theories and the case studies mentioned above, there is a body of quantitative research which has found positive peer effects on oral language skills for L1 and L2 learners (e.g., Gàmez et al., 2019; Yeomans-Maldonado et al., 2019). For L1 learners, research has shown that, at the end of preschool, children’s oral language skills were positively associated with the general abilities (Henry & Rickman, 2007) and oral expressive language abilities their peers exhibited at the beginning of preschool (Mashburn et al., 2009). Both studies found positive peer effects on oral expressive language development. Studies investigating both L1 speakers and L2 learners reported a positive association between English expressive skills development in English learners and their teachers’ and peers’ vocabulary diversity after assessing the oral language skills of the children in fall and spring of the Kindergarten year (De Houwer, 2009; Justice et al., 2011; Palermo & Mikulski, 2014). Similar results were obtained in a study of the relationship between the expressive and receptive English language performance (vocabulary, syntax) of L1 and L2 learners and their exposure to the language use of peers in multilingual kindergarten classrooms (Gàmez, 2015; Gàmez et al., 2019). These findings suggest that peers positively influence the oral language abilities of both L1 and L2 learners.

Important findings about the peer impact on language development also come from studies on school segregation. In terms of L2 learners, it has been demonstrated that when they are isolated from higher-performing L1 speaking or L2 learning peers, for example, by school or language policies, they have less access to social networks and peer resources that contribute to the learners’ social capital (Carhill-Poza, 2017; Huang, 2009).

The drawbacks of these studies are that only a small number of participants was included in each classroom and that potential differences between first and second language speakers could not be explored due to sample composition. Moreover, peer abilities were approximated by averaging the scores of the other children (Henry & Rickman, 2007; Mashburn et al., 2009) or based on recordings of classroom activities (Gàmez, 2015). They did not investigate whether the children interacted with each other during their preschool days. For example, none of the studies considered the type of relationship between children, although peer relationships include both within-peer relationships and dyad relationships such as reciprocal friendships and relationship quality (Maunder & Monkes, 2019). In the study presented in this paper, we focused on the relationship between friends because we assume that friendships – the social capital – provide a linguistic resource for children, allowing for a more in-depth quality and intensity of interaction between children.

2.3 Friendship relations and verbal interaction

Friendships positively affect the overall development of children. They offer emotional security, validation, intimacy, and affection (Vu & Locke, 2014). These features are especially prominent in mutual or reciprocal friendships, i.e., where each member of the dyad describes the other as a friend (Maunder & Monkes, 2019; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). Even though studies on friendship do not always distinguish between different friendship types (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995), the quality of reciprocated (best) friendships is better than the quality of one-sided (best) friendships. Reciprocated friendship during childhood can compensate for adaptation difficulties (Maunder & Monkes, 2019), which often occur with L2 learners. L2 children with poor language abilities can suffer peer rejection (van der Wilt et al., 2020), but according to Maudner and Monkes (2019) peer status is independent from friendship. Some children have strong friendship relations despite being rejected from their peers (Vandell & Hembree, 1994). Furthermore, Erdemir and Brutt-Grifller (2020) show emergent L2-learners’ vocabulary expands when they interact with peers they refer to as friends or “buddies”. These children benefit more from interactions with their friends as from interactions with peers.

Furthermore, friendships have an impact on the development of social competence, including advanced communication skills that sustain the relationship and allow verbal and non-verbal interaction (Borner et al., 2015). This interaction occurs more frequently between friends than non-friends and has a greater influence and developmental benefit than between non-friends (Miell & MacDonald, 2000; Rubin et al., 2008). Making friends and maintaining friendships usually means frequent communication, e.g., expressing one’s feelings, starting, or organizing a game, clarifying, or resolving conflicts. From this perspective, social interactions with friends provide a distinct context for language development and encourage the child to be an effective language partner (Philp & Duchesne, 2008). Therefore, a strong relationship between oral language development and maintenance of friendships can be expected. However, this relationship might be affected by the friends’ language skill differences.

2.4 Opportunities and challenges of language acquisition in multilingual classrooms

Very large language differences between interacting peers are a challenge for beneficial interactions and oral language development. This challenge can especially occur in multilingual classrooms. Ethnographic studies observing peer interaction in multilingual classrooms indicate that children with very different language skills interact less with each other. Specifically, kindergarten children with little knowledge of the L2 are often not integrated into play and interaction with L1-speaking peers (Blum-Kulka & Snow, 2004; Gur-Yaish et al., 2020; Blum-Kulka & Gorbatt, 2014) state that “children exhibit high skillfulness in peer teaching” (p. 192) as long as their peers master “at least rudimentary modes of communication in the new language” (p. 192). Furthermore, even if children with little knowledge of the L2 are included in interactions, the L2-input they receive by L1-speaking peers has been observed to be “highly variable and less optimal for language acquisition” (Philp & Duchesne, 2008, p. 93). The L1- and competent L2-speaking peers might address them with ungrammatical baby talk and fragmented language, neglect scaffolding, and provide little corrective feedback on children’s own language production (Philp & Duchesne, 2008).

In contrast, moderate language skill differences provide a unique opportunity. Blum-Kulka and Gorbatt (2014) observed how an L2 learner of Hebrew with more advanced L2 skills takes on the role of the ‘teacher’ while reading a book with other children speaking Hebrew as L2 (only a few months of kindergarten). The ‘teacher’ adapts to the other children by telling a story rich in gestures and repetitions. Thus, a moderate difference in language skills between peers does not only increase the likelihood of successful interaction and provide a rich context for language development to the less skillful children, but it also creates a unique opportunity for the more skillful children to engage in scaffolding and to align their language to the ZPD of their friends. Under such circumstances, friendship as a source for interdependency, joint activities, and frequent communication might be a facilitator for oral language development.

2.5 The present study

Despite the positive relationship between peer language skills and language development in children and the importance of verbal interaction for friendships, our study is one of the first to investigate the effect of friendships on children’s oral language development in multilingual classes.

For this purpose, we quantified the friendship relations of children using Social Network Analysis (SNA). Previous research using SNA has indicated that school friends are associated with academic achievement (e.g., Gremmen et al., 2019), truancy (Rambaran et al., 2017), and risk behaviors (Gremmen et al., 2019). Furthermore, friendship quality has been related to higher self-worth of children and their peer identification (Maudner & Monkes, 2019). In the present study, we investigated whether this was also true for language development.

Our first goal was to examine whether the number of friends predicts the development of oral language. Friendships offer opportunities for verbal interactions (Miell & MacDonald, 2000; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995; Rubin et al., 2008) and language use (Pellegrini et al., 1997), especially with best friends and reciprocal friends. Because of this increased opportunity to talk, listen to, and practice the language, we hypothesized that the more friends children have among their classroom peers, the stronger their language development is. We further hypothesized that a larger number of best friends and reciprocal friendships would be a predictor for stronger language development.

Our second hypothesis explored whether certain friendship constellations are more beneficial than others. Classroom observations have shown that peers ignore children with rudimentary L2 language skills and address them with baby talk and fragmented language (Blum-Kulka & Gorbatt, 2014; Philp & Duchesne, 2008). Thus, children with language skills much higher than those of their peers might lack the ability or the motivation to adapt to others’ language levels and align to their ZPD. Conversely, friends with no or small differences in the target language might also not be able to facilitate the development of each other’s language skills. Moderate differences in language skills between peers appear to provide the best opportunities for beneficial interaction and support for language learning the most (Blum-Kulka & Gorbatt, 2014). We therefore hypothesized that moderately different language skills between friends would predict greater improvements in language development than either low or high levels of differences. In other words, we expected that this relationship follows an inverted U-shaped curve.

Finally, we investigated whether the relationship between friendships and language development differs between children speaking the language of schooling as their L1 or L2. We hypothesized that students whose parents were German speakers as a second language may have fewer opportunities to improve German language proficiency at home. We expected these students to benefit more from their interactions with school friends than those whose parents were German speakers as a first language. Most investigations have either included L1 (e.g., Mashburn et al., 2009; Henry & Rickman, 2007) or L2 children (e.g., Gàmez, 2015; Grøver et al., 2018). Only Gàmez et al. (2019) included L1 and L2 children in their study, which investigated children’s expressive and receptive language as well as syntactic complexity in relation to their peers’ language use. The results show growth of expressive and receptive vocabulary in both L1 and L2 children. The sample, however, only consisted of 44 children.

In summary, previous studies have tended to document positive effects of peers’ vocabulary or overall language abilities. However, they did not specifically examine oral language acquisition in connection to the friendship relations between peers. The current study contributes to this area of research by investigating children’s friendships and oral language development in a larger sample of children speaking the language of schooling as their L1 or L2. The study aims not only to extend the knowledge on the facilitative role of friendship in oral language development but also to draw some implications for educational, school, and language policies.

3 Methods

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the university and the regional school board. Moreover, we preregistered the methods, hypotheses, and statistical analyses before data analyses (see https://osf.io/srbfn/?view_only=45c8efe03a2c43fab60a08b87f08ad41).

3.1 Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited from 11 s-grade classrooms in four Austrian primary schools. Three of the four schools that we investigated were recruited with the support of the regional school board. The regional school board distributed information about the study per e-mail to all primary schools in Styria county. Schools interested in participating in the study then contacted the researchers. One school was recruited through personal contact. One of the goals of this study was to test the hypothesis that the relationship between friendship and language development depends on the children’s linguistic status (L1 vs. L2). Therefore, we selected schools with approximately equal numbers of L1 and L2 children.

In three of the four schools, a member of the project team met the parents at a parent-teacher conference during the second week of the school year to inform them about the objectives, procedure, and duration of the study. A consent letter was distributed. In the fourth school, the principal introduced the project to the parents and distributed the information and consent. Parents whose language was not German received a consent form translated into their L1.

Consent was obtained from 214 of the 255 students in these 11 classes (83.9%). All children except one participated in data collection at T1; 207 students participated at T2.

Based on the distribution of missing data due to children’s drop out at T2 or missing parental consent (see Supplementary Table 1 for the frequencies of children in the different classes with and without parental consent), we excluded 3 classes from the analyses. An excessive number of missing data puts the validity of the social network analyses into question. For SNA, most of the nodes (children) of a given network (each classroom) need to be included so that one can draw adequate inferences on most of its connections. Previous research has shown that RSiena, the software we used to analyze our friendship network data, can handle up to 20% of missing data within a network without running into estimation problems (Huisman & Steglich, 2008). Therefore, we excluded 3 of the 11 classes that exceeded this percentage.

The final sample included 165 children (83 boys and 82 girls) distributed across 8 classes. At T1, the children were between 6 and 10 years old (M = 7.48, SD = 0.65; 94.5% of the children were 7 or 8 years old (see Supplementary Table 2 for age frequencies).

There were over 20 first languages other than German, the most frequent being Turkish, Kurdish, Romanian, Arabic, Bosnian, and Albanian (see Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 for more detailed information on demographic data). 83.3% of the children spoke German at home, 27.88% were identified by their parents as speaking German as L1, and 72.12% as speaking German as L2.

Children speaking German as L2 had been living in Austria for a mean of 3.58 years (SD = 2.40) and attended an Austrian school for a mean of 33.09 months (SD = 14.87). 51.7% of the children attended childcare after school. We collected information regarding the highest level of education of the children’s mothers (see Child and family characteristics): 1.4% of them reported that they never attended school; 10.1% that they attended compulsory school but did not complete it; 21.7% that they completed compulsory school; 21% reported having pursued a vocational training (e.g., an apprenticeship, a master examination); 20.3% possessed a high-school graduation certificate, the Matura or university entrance qualification; and 25.4% had obtained a degree from a university or similar educational institution.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Language proficiency

Children’s oral language skills in German were measured using the USB PluS, a story generation task suitable for L1 and L2 speakers (Grammel & Freunberger, 2017). The USB PluS is composed of two tasks. The first task uses four wordless picture books, each describing a simple story. Each book encompasses six images, but the fifth one is missing. Children are asked to tell the story to a badger finger puppet, guessing what may have happened in the missing image. The second USB PluS task is based on two single images, the picture of a classroom and the picture of a house. Children are asked to name all the items they see in one of these pictures.

The interview was audio-recorded, and the transcripts were analyzed by computer using the USB PluS tool (BIFIE, 2018). The USB PluS tool assesses language skills using seven indicators: task completion, verb position, verb types, connectors, nouns, verb forms, narrative language. Five of these indicators (task completion, verb position, verb types, connectors, nouns) correspond to scores that describe so-called developmental areas. The indicators, verb tenses, and narrative language are not scored. Therefore, they are not used in this study. In the present study, we used the scores of the USB PluS indicators (as described below) and not the development areas to calculate latent language proficiency. The USB PluS indicators exhibited acceptable internal consistencies (ω at T1 = 0.72; ω at T2 = 0.68; ω overall = 0.76).

Task completion indicator

Task completion captures the extent to which a pupil can verbalize actors, objects, actions, and contexts. There are two reference sentences for each picture since there are always two actors. Evaluations were out of four points: not available (0 points), implied (1 point), simple (2 points), extended (3 points), and comprehensive (4 points). Thus, the maximum score for this indicator is 48 points.

Verb position indicator

The USB PluS considers four different verb positions: second position, verb bracket, inversion, and subordination. One point can be achieved for every type of position, leading to a maximum of four points for this indicator.

Verb types indicator

The verb types are not only counted but also weighted according to their complexity and frequency of occurrence. One point is awarded for each verb category: basic verbs, specific simple verbs, and specific separable particle verbs (a specific type of verb in German). Modal verbs are weighted with two points due to their relative morphosyntactic complexity. Specific inseparable prefix verbs (also a specific type of verb in German) are rare and are acquired late, which is why they are weighted by three points. Reflexively used verbs receive an additional point for each occurrence (Freunberger, 2018, p. 5). The total score for the verb position indicator is the sum of all these values.

Connector indicator

Connectors are analyzed based on their frequency and complexity. Frequently used connectors, such as then, and, and then, are awarded one point each. Less frequently used connectors, such as but, or, and because receive two points each. The use of more complex and less frequently used connectors, such as so or relative pronouns is awarded three points each. Rarely used and more complex connectors, such as if, after, and although receive four points each.

Nouns indicator

Children’s description of the additional image is evaluated regarding the use of nouns. Simple nouns receive one point; composites nouns receive two points.

3.2.2 Additional measurements of language proficiency

We administered two additional measures of language proficiency. First, we measured children’s reading comprehension with the short version of the ELFE II, a German reading comprehension test for the second grade (Lenhard et al., 2018, short version). This test encompasses a series of exercises testing children’s word and sentence reading comprehension. Second, we asked teachers to rate L2 learners’ language proficiency with a standardized observation procedure entitled “Level descriptions DaZ” (“Niveaubeschreibung DaZ”, Döll & Reich, 2013). These additional measures are listed for methodological transparency, but we do not report or analyze this other language data as “Niveaubeschreibungen DaZ” (Doll & Reich, 2013) provides a differentiated assessment of the language level of students with German as a second language and should serve to interpret tendencies in their language development. In the present paper we analyzed data from all children.

3.2.3 Friendship relations

To assess friendship networks in the classroom, we gave children a list of their classmates’ names and asked them to indicate all their friends (all-friend-network) and their three best friends (best-friends-network). The children that did not have consent were removed from the friend network during the preparation of the data. In the network analyses, we distinguished between indegree (child is nominated by a classmate), outdegree (child nominates a classmate), and reciprocal ties (child and classmate nominate each other).

3.2.4 Child and family characteristics

Linguistic and socio-economic background variables known to influence language proficiency were collected using a parent questionnaire. In this questionnaire, we asked about children’s first language(s), whether they spoke German at home, the socioeconomic status of their parents (i.e., the highest education level of the mother as Mother’s highest level of education because previous studies (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Czinglar et al., 2015; Hoff, 2003) have suggested that mother’s highest level of education is commonly used to determine SES), the length of time the children had been an Austrian resident and attendance period at an Austrian school, and also whether they had attended afternoon childcare and extra German classes. The questionnaires were made available to parents in their respective first languages.

3.2.5 Procedure

The German language proficiency and friendship networks of the children were assessed twice: once a couple of weeks after the start of the school year (T1: September – October 2018), and a second time in spring (T2: April 2019; mean difference between T1 and T2 = 197.43 days, SD = 10.67). The assessments were carried out by a team of six examiners who were employees at the Faculty of Humanities. Two were postdoctoral researchers, two were postgraduate, and two were undergraduate students in education studies. All examiners received a half-day training to administer the USB PluS from its developers. A team of 2–3 examiners conducted the assessments in each class. In November 2018, the teachers distributed a questionnaire to parents requesting demographic and other language-related information. The different tests and questionnaires were always administered in the same order. First, the reading comprehension test (ELFE II) was carried out in the first lesson with the whole class.

After the ELFE II, the friendship questionnaire was administered. The examiner discussed the topic of friendship with the children and what it means to be friends. To make sure that all the children had a similar definition of friendship and connected friendship with verbal exchange, the experimenter read the following explanation to them:

A friend is a person with whom one likes to spend time and have fun. A friend is someone you enjoy talking to, telling them what you did during the holidays or weekends. Someone with whom you share happy and sad moments and to whom you tell exciting stories and like to hear the stories they tell.

After identifying their friends (all-friend-network), the examiner discussed with the children what a best friend means. Children then identified their three best friends (best-friend-network). This phase of data collection lasted a total of 30 min.

In the next phase, the team continued with the USB PluS. The children were told that in the next hour the examiners would like to show each of them individually some picture books and the badger finger puppet looked forward to the stories they would tell. The assessment was conducted with each child individually in a separate room. Each child received a different book at T1 and T2, selected among the four options included in the USB PluS. The stories and their order were randomized across children and classes and have been validated previously (Grammel & Freunberger, 2017). First, the children were shown one of the wordless picture books and asked to tell the story represented in the pictures. Second, they were shown the additional image included in USB PluS and asked to name all the items they could see in it. We used the classroom picture at T1 and the house picture at T2. We could not randomize the picture order because the house picture was not yet available at T1.

The assessment with the USB PluS lasted an average of nine minutes per student. We recorded children with a ZOOM H1 Handy Recorder. The sequences in which the child narrated the story and described the image were subsequently transcribed according to the guidelines of USB PluS (Grammel & Freunberger, 2017, pp. 24–28). Transcripts were analyzed with the USB PluS Tool (BIFIE, 2018) and coded for task completion (pragmatic-discursive skills), verb position (morphosyntactic skills), verb types, connectors, and nouns (lexical-semantic skills).

4 Data analysis

4.1 Language proficiency

Testing our hypotheses on each subscale of the USB PluS would have led to an inflation of the type I error associated with multiple comparisons. Therefore, we calculated latent language proficiency underlying the five USB PluS scores at T1 and T2 using structural equation modeling. We set the USB PLuS score “task completion” as the reference variable because this score is assumed to be the most saturated by language proficiency. To account for the repeated nature of our design, we allowed the latent variables at T1 and T2 and their corresponding indicators to correlate. To account for the hierarchical structure of our data (children nested in classes) and potential baseline differences across classes, we centered the indicators, i.e., the USB PLuS scores, at T1 and T2 to their respective class means at T1. Moreover, we set the indicator intercepts to zero to ensure that the latent variables captured the mean development from T1 to T2. Finally, we estimated the model parameters with a full-information maximum likelihood estimator (FIML) and robust standard errors (MLR) with the R Package lavaan (version 0.6.12; Rosseel, 2012) and extracted the factor scores. Taken together, the latent language proficiency scores for T1 and T2 account for (1) measurement error across the USB PLuS scales, (2) the repeated measure design, and (3) the hierarchical structure of the data.

4.2 Network analysis

We conducted our network analyses in the R Simulation Investigation for Empirical Network Analysis (RSiena) package (version 1.2–17; Ripley et al., 2019; Snijders et al., 2010). RSiena is designed to analyze longitudinal network and behavioral data using an actor-oriented model. This model assumes that actors (children) represented by the nodes in the network (each classroom) play a crucial role in changing their ties to other actors as well as their behavior, i.e., in the present study their language proficiency. Friendships were entered as ‘0’ (no friendship) and ‘1’ (friendship) in a square friendship matrix where the nominator (student naming their friends) was across the rows and the nominee (student being named as a friend) was down the columns. This was done for each child in each classroom.

Treatment of missing data

In RSiena, missing network data are automatically imputed (see Ripley et al., 2019). At T1, missing data in the square friendship matrix were set to 0, assuming that there was no tie. At T2, if there was a T1 observed value, then this value was used to impute the T2 value according to the `last observation carry forward’ option (Lepkowski, 1989). If there was no T1 observed value, then the value 0 was imputed. RSiena uses a similar principle for dependent behavior variables, i.e., in our case, the language proficiency variables. If there was a T1 observation of the same dependent variable, then this value was imputed at T2; if there was none, then the observation-wise mode of the variable was imputed (i.e., the mode of the variable replaces all instances of missing data). Missing covariate data were, by default, replaced by the mean of the variable. Supplementary Table 5 contains the missing counts for each covariate by classroom used in the RSiena models. The ranges for each covariate were: gender (0–1), first language (0–4), time in Austria (0–5), German spoken at home (0–4), mother’s education (0–6), time in school (0–5), and child care (0–5).

4.3 Model specification

We looked at two types of networks: all-friend (all nominated friends in the classroom) and best-friend (the top three friends in the classroom)-networks. For all models, we used a heuristic value for model convergence selected according to Ripley and colleagues (2019, p. 64): Convergence was attained when the overall maximum convergence ratio was less than 0.25 (an overall maximum convergence ratio less than 0.20 is considered as excellent).

Our analyses followed five steps. Steps 1–3 were performed in RSiena for each class separately. These steps corresponded to models of increasing complexity, and we checked convergence before moving on to the next step. If models failed to converge, we tried to identify the responsible variable(s) and removed them one by one. Note that the values of all the parameters were not established until the final model had converged. Convergence is a requirement for the analyses across the classes (step 4). If a model fails to converge at the individual class-level, then the model cannot converge across classes.

In step 1, we tested a basic model that included our main predictors (i.e., the number of friendships at T1) and dependent variable of interest (i.e., change in language proficiency between T1 and T2). In step 2, we added the covariates. In step 3, we added first language as a moderator, but the models issued from this step failed to converge. Thus, we continued to step 4 without this moderator. Step 4 and step 5 aimed at testing our hypotheses across all classes in multi-group analyses. The full details of this procedure are provided in the Supplementary Material.

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, children nominated at T1 on average around seven friends in their class (SD = 4.41); around 4.5 of these friendships were reciprocated (SD = 2.68). At the same time, they nominated around 2.5 best friends (SD = 1.03), with around half of these being reciprocated (SD = 1.01). Descriptively speaking, these averages increased slightly to T2 for the friendships and decreased slightly for the best friendships.

The means presented in Table 1 for the and language proficiency indicators (between M = 3.57 with SD = 0.84 for verb position, and M = 23.98 with SD = 7.81 for nouns) imply that scores for task completion, nouns, verb type, and connectors corresponded to a developmental stage of 2 or 3, and the verb position score to a developmental stage of 4 at T1. At T2, the language proficiency indicators (between M = 3.78 with SD = 0.58 for verb position, and M = 23.90 with SD = 8.73 for verb type) corresponded to a developmental stage of 5. These development stages are normal for this age category (Freunberger, 2018, p. 9).

5.2 Reciprocal friendships and change in language proficiency

The results of the multi-group analysis performed in RSiena to test the hypothesis that more reciprocal friendships are associated with greater changes in language proficiency (step 4) are depicted in Table 2 (all-friends-networks) and Table 3 (best-friends-networks). Parameters (log of the odds ratio) for the networks tend to be similar in magnitude and direction.

The network dynamics effects correspond to the extent to which the networks changed between T1 and T2. The effects for both kinds of networks indicated a significant negative effect of outdegree (all-friends-networks: Mean (β) = -0.82; best-friends-networks: Mean (β) = -1.33) and a significant positive effect of reciprocity (all-friends-networks: Mean (β) = 1.31; best-friends-networks: Mean (β) = 1.33). This indicates that friendships tended to be avoided (negative outdegree) unless there was a reciprocation of a friendship from T1 to T2 (positive reciprocity; Steglich et al., 2006).

The effects of the behavior dynamics test the extent to which the network parameters and covariates at T1 predicted the change in language proficiency between T1 and T2. These effects revealed a marginally significant effect of reciprocity for the all-friends-networks (Mean (β) = 0.10, p = .084) and a significant effect of reciprocity for the best-friends-networks (Mean (β) = 0.46, p = .027). Having more reciprocal best-friendships at T1 thus predicts greater improvement in oral language proficiency. The other covariates did not appear to predict language proficiency change in either kind of friendship (all-friends-networks: -0.13 ≤ Mean (β) ≤ 0.36; best-friends-networks: -0.15 ≤ Mean (β) ≤ 0.38; all ps > 0.05).

Finally, we found a significant linear effect in both networks (all-friends-networks: Mean (β) = 0.16; best-friends-networks: Mean (β) = 0.18), which indicates that the oral language proficiency of the students increased from T1 to T2. The quadratic shape of the same effect was nonsignificant (all-friends-networks: Mean (β) = -0.01; best-friends-networks: Mean (β) = -0.01).

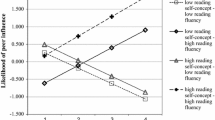

6 Friendship constellations and change in language proficiency (step 5 results)

The results of the Bayesian mixed effects model investigating the relationship between friendship constellations and the change in language proficiency (step 5) are reported in Table 4. This analysis revealed a significant negative quadratic effect of the weighted ties (b = -0.02, p = .021; computed with the null hypothesis that the effect = 0). This result supports our hypothesis of an inverted U-shaped relation between the weight that represents the difference in language proficiency between students and their friends as well as the nature of the friendship (best friend, reciprocal friend, unilateral friendship), and the respective change in the language proficiency of the students (see Fig. 1).

Contrary to our hypothesis that the friendship constellation effect would be stronger for students speaking German as L2, Table 4 shows that the interaction between the quadratic effect of ties and the first language was not significant (b = -0.02), neither was the interaction between the linear effect of ties and the first language (b = -0.04). None of the covariates demonstrated significant effects (-0.98 ≤ b ≤ 0.41).

The conditional ICC for the classrooms was 2.8% variance explained suggesting that minimal variance in language change was due to the effects of different classrooms. The conditional R2 for the fixed effect was 20.7%, 95% CI [11.7%, 30.7%] variance explained suggesting that a substantial variance could be explained by our variables of interest and covariates. This result supports the substantive significance of the effect of reciprocal ties affecting improvement in language ability.

Language change between T2 and T1 as a function of the weights attributed to each node (i.e., child) at T1. Each dot represents a child. Dots of the same color correspond to children from the same class. Weights reflect the interaction between friendship type and language proficiency differences between children and their friends

We performed the step 5 analysis twice more: once with the weights representing only the type of friendship relationship and another time with the weights based only on absolute language differences. There was no effect for the type of friendship relationship model, but a significant quadratic effect for the absolute language differences (p < .05). The effect size was larger, however, when the combined effect of type of friendship and absolute language differences were present (\(b\) = -0.02; Table 4) than in cases with language differences only (\(b\) = -0.002, 95% CI [-0.004, -0.000]), suggesting that the combination of the type of friendship and absolute language differences between friends was a better predictor for the change in language proficiency (see Supplementary Tables 6 & 7, and Supplementary Fig. 1 for a more complete report of these two analyses). This claim is further supported by the conditional R2 for the fixed effects of the language differences only model (16.9%, 95% CI [8.2%, 26.5%]), which explained about 4% less variance than the combination of the type of friendship and absolute language differences model.

7 Discussion

In this article, we investigated the role of friendships in language development in children. For this purpose, we asked 165 s-grade students to identify their friends, and we tested their language skills both at the beginning of the school year and six months later. We analyzed these data using SNA. The results showed that the more reciprocal best friendships the children had at the beginning of the school year, the more their oral language skills improved. Furthermore, we found an inverted U-shaped relation between the change in oral language skills and the weight representing the difference in language proficiency between a pupil and his friends and the nature of this friendship. We did not find any differences between children speaking the language of schooling as L1 or L2.

In partial agreement with our hypothesis 1 (step 4, Multi-group analyses), our results show that more reciprocal best friendships predict a greater improvement of oral language proficiency. Former studies on classroom peer effects and language development found positive effects of peer language proficiency on oral language skills (e.g., Mashburn et al., 2009). These studies, however, did not examine the nature of relationships between peers in the classroom, which may be an indication of the quantity and quality of verbal interaction. Children do not engage in interaction with all of their peers, but they invest in verbal and non-verbal interaction to achieve their “social goals of establishing friendship” (Erdemir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020; Philp & Duchesne, 2008, p. 85). On that basis, there is a difference between the level of social contact, conversation, and positive impact between friends versus non-friends (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995).

Moreover, the effect of the number of reciprocal friends on oral language development was marginally significant. Thus, the number of reciprocal best friends seems to be more strongly related to oral language development than the number of reciprocal friends. This result might be attributed to the fact that children tend to engage with their best friends more often and therefore their verbal interactions might be more intensive. Best friends tend to share similar interests, e.g., games or other themes. Interactions in which individual interests are involved are known to have a facilitative role in language acquisition (Erdemir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020). In their case study, Erdemir and Brutt-Griffler (2020) show that “the vocabulary acquired by the child from his two “buddies” is equivalent to 48% of the vocabulary learned from all other peers” (Erdemir & Brutt-Griffler, 2020, p. 19). The study used an ethnographic approach to observe the child’s interaction with his peers, but friendship types were not collected. However, from the observations, it appears that the child spent the most time with these two peers and behaved toward them as they would be best friends. The result of this observation, that friendship facilitates vocabulary growth, could be an explanation for the predictive role of best friends in children’s language development found in our study.

Furthermore, the results of this study (step 5) confirmed our second hypothesis that some friendship constellations are stronger predictors of oral language development than others. Based on the concept of language mediation through experts (Blum & Kulka, 2014; Swain et al., 2002), we assumed that children benefit most if the differences in language skills between students and their friends are neither too big nor too small; thus, enabling support for each other’s language development by aligning to ZPD. As some case studies show, children’s level of language skills plays a fundamental role in either establishing or being excluded from friendship relations (Blum-Kulka & Gorbatt, 2014). There is still a lack of evidence, however, on the extent to which the difference of the friend’s language skills predicts the development of one’s own language skills when friendships are already established. We found an inverted U-shaped relation between language difference and friendship weights on the one hand and oral language development on the other. These results suggest that moderate differences in language skills between close friends facilitate oral language development.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find any moderation by language background, which correspond to the findings of Gàmez et al. (2019). Neither the relationship between the number of friendships and oral language development nor the inverted U-shaped relation was stronger for children speaking the language of schooling as L2 than for children speaking it as L1. It might be that, in our sample, the proportion of children speaking German as L1 was too low to detect an effect of their first language.

In our analyses, we controlled several covariates, none of which were significant in the combined analysis. This non-significant result might be due to the fact that these covariates were not independent of each other and, therefore, unlikely to reach significance when all included in the same analysis (see multicollinearity). Another explanation is the relatively short distance between the two tests. Other studies using a longer period (e.g., Halle et al., 2012) find the effects of parental education, the duration of exposure to the L2, and participation in early childhood care as some of the predictors of early L2 proficiency development.

7.1 Limitations

In the present study, children’s interaction was approximated by using SNA. With this unique approach to the study of friendship relations, the current investigation complements prior peer studies (e.g., Mashburn et al., 2009). Nevertheless, actual interaction between friends was not observed. Future studies might address this limitation by observing the frequency, length, and quality of interaction between children.

The current study shows that moderate language differences between friends, especially between best friends, is beneficial for their oral language development. To our knowledge, our study is the first to show this effect and, therefore, should be replicated. If this result were to be replicated, it would be interesting to investigate whether both friends benefit equally. The less proficient child is likely to benefit linguistically more from being a friend with a child who is more expert in the language (e.g., by learning new words and turns of phrase). It may also be that the advanced child deepens his language knowledge by engaging in processes of meaning negotiation and meaning construction. We were not able to investigate these hypotheses because we did not have sufficient statistical power to carry out the necessary analyses. Future studies should shed light on this fundamental question.

Another limitation of this study is that our results are correlational. We found a correlation between friendships at T1 and the change in language proficiency between T1 and T2. However, our paradigm does not allow us to specify the type of relationship between these variables. One possible explanation for these results is that friendships enhance language development because they provide opportunities to practice the language. However, we cannot rule out the hypothesis that other variables simultaneously influenced children’s friendships and language development (e.g., inter-individual differences in executive functions) or that children with better language learning abilities are more likely to make friends (e.g., Blum-Kulka & Snow, 2004). Even though a longitudinal design allows for stronger evidence than cross-sectional data, only an experimental manipulation could demonstrate causality; however, for obvious ethical and practical reasons, it is not possible to experimentally manipulate children’s friendships.

7.2 Conclusion

In summary, the results of our study emphasize the importance of friendships in the classroom for language development. The results provide evidence that peer-peer interactions are important for the development of language skills. Specifically, moderate differences in language ability may offer the most improvement in language skills in both L1 and L2 learners. These differences are further enhanced when children are best friends but have moderately different language ability.

The study findings reinforce the argument that classrooms and schools should be safe areas of reciprocity, belonging, and positive emotionality in order to provide an optimal environment for friendships and language development. On a didactic level, a deeper understanding of the relationship between positive social relationships and language development would enable development of didactic settings and social forms of teaching. Furthermore, on a school policy level, our results can imply that actively regulating classroom compositions may prove beneficial for language development (for a similar line of reasoning for reading performance see Groeneveld & Knigge, 2015).

In light of current language policies, our findings provide evidence for the important role of positive peer relationships in the oral language development of L2 learners. European countries have introduced the additional support classes for school beginners where children with insufficient knowledge of the language of instruction are taught most of the time in separate classrooms (FMAESR, n. d.). Additional language learning support may have some benefits for beginning language learners for a limited time, though, children benefit more from language immersion with short periods of additional language support (Siarova & Essoemba, 2014). Future work should attempt to identify other influences that may be responsible for improved language skills in peer-peer interactions with L1 and L2 learners.

References

Atkins-Burnett, S., Xue, Y., & Aikens, N. (2017). Peer effects on children’s expressive vocabulary development using conceptual scoring in linguistically diverse preschools. Early Education and Development, 28(7), 901–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1295585

Aukrust, V. G., & Rydland, V. (2011). Preschool classroom conversations as long-term resources for second language and literacy acquisition. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(4), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.01.002

BIFIE - Bundesinstitut für Forschung, Innovation und Entwicklung (2018). USB PluS Toolhttps://www.usbplus.at/downloads/ Accessed 28 January 2022.

Blum-Kulka, S., & Snow, C. (2004). Introduction: The potential of peer talk. Discourse Studies, 6(3), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445604044290

Blum-Kulka, S., & Gorbatt, N. (2014). “Say princess”: The challenges and affordances of young hebrew L2 novices’ interaction with their peers. In A. Cekaite, S. Blum-Kulka, V. Grøver, & E. Teubal (Eds.), Children’s peer talk: Learning from each other (pp. 169–193). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139084536.013

Borner, K. B., Gayes, L. A., & Hall, J. A. (2015). Friendship during childhood and cultural variations. International Encyclopedia of Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition), 442–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.23184-X

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(3), 71–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Carhill-Poza, A. (2017). “If you don’t find a friend in here, it’s gonna be hard for you”: Structuring bilingual peer support for language learning in urban high schools. Linguistics and Education, 37, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2016.09.001

Czinglar, C., Korecky-Kröll, K., Uzunkaya-Sharma, K., & Dressler, W. U. (2015). Wie beeinflusst der sozioökonomische Status den Erwerb der Erst- und Zweitsprache? Wortschatzerwerb und Geschwindigkeit im NP/DP-Erwerb bei Kindergartenkindern im türkisch-deutschen Kontrast. [How does socio-economic status influence the development of first and second language? Vocabulary learning and speed in NP/DP among kindergarten children in Turkish-German contrast]. In A. Ziegler & Klöpke, K.-M. (Eds.) Deutsche Grammatik in Kontakt. Deutsch als Zweitsprache in Schule und Unterricht. Vol. 64 (pp. 207–240). DeGruyter. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110367171-010

De Houwer, A. (2009). Bilingual first language acquisition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Donnelly, S., & Kidd, E. (2021). The longitudinal relationship between conversational turn-taking and vocabulary growth in early language development. Child Development, 92(2), 1?17. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13511

Döll, M., & Reich, H. H. (2013). Niveaubeschreibungen für die Primarstufe. Deutsch als Zweitsprache [Level descriptions of the primary school. German as second language]. Sächsisches Bildungsinstitut: Radebeul.

Ellis, R. (2012). Language teaching research and language pedagogy. Malden, Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Erdemir, E., & Brutt-Griffler, J. (2020). Vocabulary Development through peer interactions in early childhood: A case study of an Emergent Bilingual child in Preschool. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(3), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1722058

European Council (2018). Commission staff working document. Proposal for a council recommendation on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52018SC0174 Accessed 28 January 2022.

Federal Ministry Republic of Austria Education, Science and Research (FMAESR) (n.d.). Additional support classes for German. https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/en/Topics/school/krp/add_sup_cl_german.html Accessed 28 January 2022.

Freunberger, D. (2018). Referenzprofile des Instruments USB PluS [Reference profiles of the instrument USB PluS]. Salzburg: BIFIE. https://www.usbplus.at/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/USB_Referenzprofile_2018.pdf Accessed 28 January 2022.

Gámez, P. B. (2015). Classroom-based English exposure and English language learners’ expressive language skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.01.007

Gámez, P. B., Griskell, H. L., Sobrevilla, Y. N., & Vazquez, M. (2019). Dual language and English-only learners’ expressive and receptive language skills and exposure to peers’ language. Child Development, 90(2), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13197#

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning. Teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom (2nd ed.). Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Grammel, E., & Freunberger, D. (2017). Handbuch USB PluS - Unterrichtsbegleitende Sprachstandsbeobachtung, Profilanalyse und Sprachbildung [Handbook USB PluS - language observation during lesson]Salzburg: BIFIE. https://www.usbplus.at/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Handbuch_USB-PluS_2017_web.pdf Accessed 28 January 2022.

Gremmen, M. C., Berger, C., Ryan, A. M., Steglich, C. E. G., Veenstra, R., & Dijkstra, J. K. (2019). Adolescents’ friendships, academic achievement, and risk behaviors: Same-behavior and cross-behavior selection and influence processes. Child Development, 90(2), e192–e211. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13045

Groeneveld, I., & Knigge, M. (2015). Moderation primärer sozialer Disparitäten im Leseverständnis in Abhängigkeit vom wahrgenommenen Verhalten der Lehrkraft und der Klassenzusammensetzung [Moderation of social disparities in reading achievement through classroom factors]. Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung, 5(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35834-014-0115-7

Grøver, V., Lawrence, J., & Rydland, V. (2018). Bilingual preschool children’s second-language vocabulary development: The role of first-language vocabulary skills and second-language talk input. International Journal of Bilingualism, 22(2), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916666389

Gur-Yaish, N., Hijazi, S., Mazareeb, E. A., & Schwartz, M. (2020). ‘She doesn’t speak English, she speaks Hebrew’: A case of language socialization of a quadrilingual girl. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 41, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1854770

Halle, T., Hair, E., Wandner, L., McNamara, M., & Chien, N. (2012). Predictors and outcomes of early vs. later English language proficiency among English language learners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.07.004

Henry, G. T., & Rickman, D. K. (2007). Do peers influence children’s skill development in preschool? Economics of Education Review, 26(1), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.09.006

Hoff, E. (2003). Causes and consequences of SES-Related differences in parent-to-child speech. In M. H. Bornstein, & R. H. Bradley (Eds.), Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development (pp. 146–160). Routledge.

Huisman, M., & Steglich, C. (2008). Treatment of non-response in longitudinal network studies. Social Networks, 30(4), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2008.04.004

Huang, L. (2009). Social capital and student achievement in norwegian secondary school. Learning and Individual Differences, 19, 320–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2008.11.004

Justice, L. M., Petscher, Y., Schatzschneider, C., & Mashburn, A. (2011). Peer effects in preschool Classrooms: Is children’s language growth associated with their classmates’ skills? Child Development, 82(6), 1768–1777. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01665.x

Lenhard, W., Lenhard, A., & Schneider, W. (2018). ELFE II - Ein Leseverständnistest für Erst- bis Siebtklässler - version II/3., corrected edition. [ELFE II - A reading comprehension test for first to seventh grade - version II/3] Göttingen: Hofgrefe.

Lepkowski, J. M. (1989). Treatment of wave nonresponse in panel surveys. In D. Kasprzyk, G. Duncan, G. Kalton, & M. P. Singh (Eds.), Panel surveys (pp. 348–374). Wiley.

Karem, R. W., & Hobek, A. (2022). A peer-mediated approach to support emergent bilingual preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 58, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.08.003

Mashburn, A. J., Justice, L. M., Downer, J. T., & Pianta, R. C. (2009). Peer effects on children’s language achievement during Pre-Kindergarten. Child Development, 80(3), 686–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01291.x

Maunder, R., & Monkes, C. P. (2019). Friendships in middle childhood: Links to peer and school identification, and general self-worth. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 37, 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12268

Miell, D., & MacDonald, R. (2000). Children’s creative collaborations: The importance of friendship when working together on a musical composition. Social Development, 9(3), 348–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00130

Newcomb, A. F., & Bagwell, C. L. (1995). Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117(2), 306–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.306

Palermo, F., & Mikulski, A. (2014). The role of positive peer interactions and English exposure in Spanish-speaking preschoolers’ English vocabulary and letter-word skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.07.006

Pellegrini, A. D., Galda, L., Flor, D., Bartini, M., & Charak, D. (1997). Close Relationships, individual differences, and early literacy learning. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 67(3), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1006/jecp.1997.2415

Philp, J., & Duchesne, S. (2008). When the gate opens: The interaction between social and linguistic goals in child second language development. In J. Philp, R. Oliver, & A. Mackey (Eds.), Second language acquisition and the younger learners: Child’s play? (pp. 83–103). John Benjamin.

Philp, J., Oliver, R., & Mackey, A. (Eds.). (2008). Second language acquisition and the younger learners: Child’s play. John Benjamin.

Rambaran, J. A., Hopmeyer, A., Schwartz, D., Steglich, C., Badaly, D., & Veenstra, R. (2017). Academic functioning and peer influences: A short-term longitudinal study of network–behavior dynamics in middle adolescence. Child Development, 88(2), 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12611

Ripley, R. M., Snijders, T. A. B., Boda, Z., Voeroes, A., & Preciado, P. (2019). Manual for RSIENA. University of Oxford, Nuffield College.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rubin, K., Fredstrom, B., & Bowker, J. (2008). Future directions in… Friendship in childhood and early adolescence. Social Development, 17(4), 1085–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00445.x

Siarova, H., & Essoemba, M. A. (2014). Language support for youth with a migrant background: Policies that effectively promote inclusion (4 Issue No.). SIRIUS. SIRIUS Network Policy Brief Series.

Schwartz, M., & Gorbatt, N. (2017). "There is no need for translation: She understands": Teachers’ mediation strategies in a preschool bilingual classroom. Modern Language Journal, 101(1),143–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12384

Snijders, T. A. B., Koskinen, J., & Schweinberger, M. (2010). Maximum likelihood estimation for social network dynamics. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 4(2), 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-AOAS313

Steglich, C., Snijders, T. A. B., & West, P. (2006). Applying SIENA: An illustrative analysis of the coevolution of adolescents’ friendship networks, taste in music, and alcohol consumption. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241.2.1.48

Swain, M., Brooks, L., & Tocalli-Beller, A. (2002). Peer–peer dialogue as means of second language learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 22, 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190502000090

Vandell, D., & Hembree, S. (1994). Peer social status and friendship: Independent contributors to children’s social and academic adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40(4), 461–477.

van der Wilt, F., van der Veen, C., van Cruistum, C., & van Oers, B. (2020). Language abilities and peer rejection in kindergarten: A mediation analysis. Early Education and Development 31(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2019.1624145

Vu, J. A., & Locke, J. J. (2014). Social network profiles of children in early elementary school classrooms. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 28(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2013.850128

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Justice, L. M., & Logan, J. A. R. (2019). The mediating role of classroom quality on peer effects and language gain in pre-kindergarten ECSE classrooms. Applied Developmental Science, 23(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1321484

Acknowledgements

Special thanks from the team of authors to Lisa Niederdorfer for the support of this publication due to her cooperation in the project at the University of Graz from 2018 to 2020.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bushati, B., Kedia, G., Rotter, D. et al. Friends as a language learning resource in multilingual primary school classrooms. Soc Psychol Educ 26, 833–855 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09770-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09770-6