Abstract

High-quality helping behavior is essential for effective peer interaction and learning. This study focused on ethnic group composition and the quality of group interaction as predictors of individual mathematics performance. Video-observations of 92 fifth-grade students working in groups balanced on mathematics performance level were analyzed. We expected a difference in the quality of interaction and test scores of native and non-native students. Multilevel analysis identified process regulation and giving answers as positive predictors of mathematics performance, whereas giving or applying explanations contributed negatively. Non-native students generally had lower achievement scores than native students. Non-native students working in ethnically heterogeneous groups performed better than did students working in homogenous groups. Homogeneous groups used more high-quality helping behaviors and engaged more often in task-oriented behavior. Heterogeneous groups engaged more often in low-quality helping behaviors. Working with native students may have been conducive to non-native students’ understanding of word problems in realistic mathematics education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Irrespective of governmental attention paid to the desegregation of socioeconomic and ethnic minorities, it seems that in many countries there still is a strong concentration of ethnic minorities located in economically disadvantaged areas such as large cities and conglomerations (Di Bartolomeo 2011; Zhan 2015). This concentration leads to high proportions of ethnic minority students in the schools situated in these economically disadvantaged areas. This pattern of segregation occurs in many European countries, such as the Netherlands, Great Britain, and Sweden (Schönwälder 2007), but also in the United States (United States Government Accountability Office 2016).

The language abilities of many students from ethnic minorities lag behind their national or native peers already at the start of primary school (e.g., Kieffer 2008). These students are often confronted with the task of learning subject-specific information by reading in a language that they do not fully master. Limited language proficiency in the national language partially explains lower academic performances of non-native students as compared to their native peers OECD 2010). In the current article, the term native refers to students whose parents are both of Dutch origin (i.e., non-migrant; those who speak Dutch as a native language), whereas non-native designates those students of whom at least one of his or her parents were born in other, often non-Western European countries (i.e., first or second generation migrants; those who speak Dutch as a minority language; Karssen et al. 2017).

Oortwijn et al. (2005) found that non-native students’ lack of proficiency in the national language is especially detrimental for their performance on contextualized mathematics tasks when compared to native students. In the present study, we focus on native and non-native students’ mathematical performances in the context of cooperative learning. Specifically, we will examine if ethnic group composition and the quality of group interaction are predictors of individual mathematics performance. In addition, we examine if ethnically heterogeneous and homogeneous groups engage in different types of cooperative behaviors during peer interaction.

1.1 Test performance for realistic mathematics

Since 1970, a reform of mathematics education, characterized by an increasing emphasis on the application of contextualized mathematical skills and solving realistic mathematics problems, has taken shape internationally (e.g., Kilpatrick et al. 2001). Realistic mathematics problems are strongly connected to the real world and are contextualized so that students can imagine the problem context. For example, students see a drawn piece of land and are given the size of the area. Students are then asked what size each parcel will have if 20 houses are built on this land, given that all parcels need to be of the same size (Hickendorff 2013a). These types of contextual problems have become the core in both everyday mathematics lessons and assessments in elementary schools (Hickendorff 2013a), and in recent international comparative PISA-studies (Program for International Student Assessment; OECD 2010).

In several countries, mathematics education evolved towards the predominant use of contextual problems. Because these contextual problems can be characterized by realistic assignments presented in a narrative, they strongly call on (elementary) students’ language proficiency (Hickendorff 2013a, b). Not only do students need to understand the contextual problems correctly, but preferably, they also vocalize their solutions, listen to classmates’ ideas, and discuss appropriate problem-solving strategies (Freudenthal 1973). This places heavy demands on students’ vocabulary and communication skills (Hickendorff 2013a, b). More importantly, language proficiency and mathematical competence are related. For example, Bradby (1992) examined the mathematics performance of students who learn English as their second language and found a strong relation between their English proficiency and mathematics performance. Especially the linguistic challenge entailed in contextual problems negatively affects the mathematics performance of non-native students (e.g., Walzebug 2014). For instance, Abedi and Lord (2001) reported that contextual problems are more difficult to non-native speakers if these problems (a) incorporate many abstract representations and relative or conditional clauses, (b) are written in a passive voice, (c) use relatively long sentences, and (d) contain a high level of unfamiliar vocabulary.

1.2 Reducing the gap in mathematics performance through cooperative learning

Reducing the gap in educational achievement between non-native students from ethnic minorities and native students from the national majority is of great importance for all countries that face an increase of schools with high concentrations of students with immigrant backgrounds, especially considering that the percentage of non-native school-going students will keep growing (e.g., Statistics Netherlands 2003; US GAO 2016). Over the past decades, research has consistently shown the potential of cooperative learning to overcome educational disadvantages, improve interethnic relations, and enhance academic performance (e.g., Johnson and Johnson 2009).

During cooperative learning, a learning situation is created in which students interact, give and receive information, and construct knowledge collaboratively (Johnson and Johnson 2009; Webb 2009). Many schools use cooperative learning in their mathematics classes to improve learning outcomes (e.g., Norenes and Ludvigsen 2016), with the added benefit for multi-ethnic schools that cooperative learning creates a learning environment in which students are challenged to actively practice and develop their language skills (Zakaria et al. 2010).

In order for cooperative learning to reach its full potential, students need to help each other by giving and receiving explanations. Hence, students’ helping behavior is essential for establishing effective peer interaction (e.g., Webb et al. 2002). However, the quality of students’ helping behavior can vary to a large extent and can be placed on a continuum of levels of elaboration ranging from low to high (Webb 2009). Low-quality helping behavior is often characterized by nonresponse to questions, or giving and receiving unelaborated help, such as solutions or calculations without further explanation (Webb et al. 2002). Webb and Mastergeorge (2003) examined the helping behaviors of seventh-grade students working in small groups on mathematical problems. Analyses of students’ collaboration showed that receiving low-quality help is less beneficial for learning gains because it implies fewer opportunities for clarifications and cognitive restructuring.

High-quality helping behavior comprises asking for, giving, receiving, and applying elaborate explanations, which are conceptualized as detailed or descriptive problem-solving strategies (Webb et al. 2002; Webb and Mastergeorge 2003). Giving elaborate explanations stimulates cognitive restructuring. For example, by explaining to a peer how he or she can calculate the size of each parcel after having built 20 houses on a piece of land of which the area size is given. The help giver then elaborates his or her thinking and rehearses and internalizes (mathematical) procedures (King 2002; Webb 2009). Similarly, receiving elaborate explanations positively predicts achievement if the explanations are timely, relevant, and understandable (Nelson-Le Gall 1992), and if students have the opportunity to apply these explanations (Vedder 1985).

1.3 Language competences, group composition, and helping behavior

Because many non-native students have problems with the linguistic challenges entailed in contextual mathematics problems (Abedi and Lord 2001), working together in groups can be conducive to their understanding of the task. Students can help each other by actively sharing their ideas and mathematical knowledge. Even in groups homogeneous in mathematical competence there are many opportunities for cognitive restructuring, particularly for students of non-native origin who are stimulated to vocalize their thoughts and ask questions to their peers. Provided that the cognitive gap of mathematical competence between students is not too large (e.g., a high-ability student paired with a medium-ability student), working in groups with students varying in mathematical competence can be beneficial for mathematics learning (Cohen 1994; Gillies and Haynes 2011). In such groups, students with lower mathematical proficiency may benefit from help provided by students that are more competent. The current study, therefore, investigates groups in which students vary in mathematical competence. We assume that the beneficial effect of heterogeneous group composition is similar for students of native and non-native origin. This is important because the current study was conducted in ethnically mixed schools and classes. Given that many students of non-native origin have limited proficiency in the native language, working in groups could benefit these students even more if they would have the opportunity to work together with students with different mathematical competences and with native students highly proficient in the national language. Students of native origin can support non-native students’ understanding of word problems in realistic mathematics education.

In a cooperative learning context, students proficient in the national language (e.g., mostly students with native backgrounds) ideally take on a tutor-role whenever they experience that less proficient peers (e.g., students with non-native backgrounds) have difficulties in understanding contextual problems. Proficient students may provide linguistic scaffolds such as rephrasing the contextual problem at an understandable level (Vedder 1985). In addition, they can give explanations to make sure the students of non-native origin understand the contextual problems, monitor whether or not their peers understood the explanation, and try to elaborate their peers’ prior knowledge (Roscoe and Chi 2007). If students achieve this type of tutoring, they engage in high-quality helping behaviors. Both students of native and non-native origin working in groups in which students vary in their proficiency of the national language are expected to grow in mathematics achievement because both giving and receiving explanations is considered to be beneficial for learning (Webb 2009; Webb and Mastergeorge 2003).

A first general aim of this study is to examine which types of students’ helping behavior enhance mathematical learning gains. Our second goal is to examine whether participating in either ethnically homogeneous or heterogeneous groups affects individual mathematics achievement. Given the paucity of studies examining the interaction processes of ethnically, and consequently linguistically, heterogeneous and homogeneous groups, it is not clear whether the assumed relation between these different group compositions and mathematics performance is linked to the fact that heterogeneous groups use more high-quality helping behavior during group work than homogeneous groups, or that other processes are involved. Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

-

1.

What is the relation between the quality of students’ helping behavior and individual mathematics performance?

-

2.

Does mathematics performance vary for (a) students of native and non-native origin, and (b) for ethnically heterogeneous and ethnically homogeneous groups?

-

3.

Do ethnically heterogeneous groups use more high-quality helping behaviors during group work than ethnically homogeneous groups?

Regarding the first question, the general hypothesis is that the quality of help given to other students is a good predictor of mathematics achievement, both for students of native and of non-native origin: Higher quality corresponds to higher achievement. High-quality helping behavior is expected to predict higher achievement, whereas low-quality helping behavior is not. Following Bradby (1992) and Abedi and Lord (2001), we expect that the mathematical performance of native students is better than that of non-native students. In addition, we expect that non-native students collaborating in ethnically heterogeneous groups (i.e., with students of native origin) perform better than students of non-native origin working in ethnically homogeneous groups (i.e., groups with only students of non-native origin). Regarding the third question, we hypothesize that students working in heterogeneous groups (with a combination of students of native and non-native origin) more often initiate high-quality behaviors than students in homogeneous groups (with only students of non-native origin).

The current study’s relevance is that it seeks to address the understudied relation between the nature and emergence of helping behavior in cooperative learning and group characteristics such as the group’s composition. Moreover, the relation between the quality of students’ helping behavior, group composition, and learning gains hitherto has mostly been examined by means of aggregating individual scores for each team and performing analyses (t tests and ANCOVA’s) at the group level (e.g., Gillies and Khan 2008; Webb and Farivar 1994). The present study, instead, takes into account the hierarchical structure of the data: Multilevel analysis is performed to examine the interplay between helping behavior, ethnicity, ethnic group composition, and mathematical learning gains. In doing so, our research clarifies mechanisms underlying effective student helping behavior and subsequent learning gains, while taking into account ethnicity at the student level as well as the role of ethnic group composition.

2 Method

The data for this article originated from a study by Oortwijn et al. (2008a) that focused on student background characteristics (i.e., prior mathematical knowledge and motivation for cooperative learning) and teacher stimulation as key factors in the effectiveness of a mathematics curriculum implementing cooperative learning. An informed consent procedure was followed: Parents or caregivers received an information letter that explained the goal, methods, and procedures of the study. Parents could withdraw their children from participating in the study.

2.1 Participants

The original study (Oortwijn et al. 2008a) took place in 10 multiethnic fifth-grade classes from 10 schools in the Netherlands where a nine-lesson mathematics curriculum was implemented. Based on their prior mathematics performance, 172 students were placed in either of two types of heterogeneous mathematic competence groups each composed of three to four students (high and average competence or average and low competence) before the start of the curriculum. Without prior notification, each group was videotaped during two lessons, preferably once during lessons 1–4 and once during lessons 5–9. The original research team (Oortwijn et al. 2008a, b) randomly chose and wrote down which lessons were videotaped. Based on this description, we have selected episodes suitable for further analyses for the current study. We decided to use video recordings taken in the 5–9 lessons, because students were expected to have adjusted to the presence of the audio-visual equipment by then and were supposed to have learned (and used some of) the implemented rules for cooperative learning.

Based on these criteria, video-observations of 25 groups consisting of 46 boys and 46 girls (Mage = 135.2 months, SD = 6.4), qualified for the current analysis. The selected subsample consisted of 35 students of native origin and 57 students of non-native origin from eight fifth-grade classes from eight different schools. Group composition was based on mathematical performance level: The ethnic composition of the groups was not manipulated. In 11 of the groups, all students were of non-native origin (i.e., homogeneous groups), whereas both students of native and non-native origin collaborated in 14 groups (i.e., heterogeneous groups).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Pretest

In the Netherlands, a curriculum-independent test developed by the Dutch National Institute for Educational Measurement (CITO) is widely used in primary schools to monitor students’ learning progress in mathematics. This national CITO-test (α = .94; Evers, Van Vliet-Mulder, and Groot 2000) was used to assess students’ prior knowledge of the mathematical domains measurement, time, and numbers and operators. This open-ended test was administered and scored by the teachers, as it is part of the National Curriculum Testing System.

2.2.2 Posttest

Students filled out a curriculum dependent posttest at the end of the curriculum. The posttest consisted of seven multiple-choice items covering five mathematical areas treated in the curriculum (i.e., percentages, fractions, pie charts, scale, and area). For example, children had to decide which of the three drawn islands was the biggest using a grid or they had to calculate how much money painting a house would cost. A point was given for each correct answer. Resulting scores were converted to correspond to grades on a ten-point scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 10 (excellent). Reliability analysis revealed satisfactory internal consistency (α = .75), and Pearson’s correlation test showed a significant correlation (r = .77, p < .01) between the pre- and posttest (Oortwijn et al. 2005).

2.2.3 Student helping behavior

The observation scheme used to gather information on the quality of student’s helping behavior was based on frameworks originally developed by Gillies (2006), Webb and Mastergeorge (2003), and Vedder (1985). In the present study, several types of students’ helping behaviors such as asking for help, giving help, and applying help have been combined into one coding scheme (presented in Table 1). Different types of high-quality helping behavior are grouped in four categories: Ask explanation (i.e., asking for help or elaboration), give explanation (i.e., giving or complementing explanations with reasons or arguments), and apply explanation (i.e., summarize, paraphrase, or use explanation in solving a problem). We added process regulation as a fourth category of high-quality helping behavior to compile information on the regulation of activities at the highest level of social interaction, that is, at the group level (Saab 2012). Process regulation comprises activities such as planning (i.e., posing new questions, disagreements, and proposing strategies), monitoring (i.e., checking if peer understands and reminding each other of basic rules), and evaluating (i.e., positive feedback). Similarly, four types of low-quality helping behavior have been coded: Ask answer, give unelaborate answer (i.e., give mathematical procedure without further explanation), give answer (i.e., merely give solutions or confirmation), and apply answer (i.e., mechanically echoing or adopting answers). The last two codes, on-topic process and on-topic organizational, were included to examine other (individual) task-oriented behaviors.

2.3 Coding procedure

The Multiple Episode Protocol Analysis tool (MEPA, version 4.10; Erkens 2005) was used to code the transcripts of 25 video-observations and resulted in 7267 utterances (Mlength transcript = 290.68, SD = 133.88). Two coders (i.e., the first author and an independent researcher blind to the purposes of this study) practiced the coding schemes by coding two transcripts. The inter-rater reliability (κ = .85) was calculated on approximately 10% of the transcripts coded independently by the coders and turned out to be of sufficient quality (Strijbos et al. 2006).

2.4 Procedure

The pretest was administered prior to the cooperative mathematics-learning curriculum, and students were placed in narrow heterogeneous groups. Teachers received a 2-h training that focused on the correct implementation of the mathematics curriculum and on using rules for cooperative learning effectively (Oortwijn et al. 2008b). The teachers introduced these ground rules to their students during two training lessons. Such ground rules as “everyone listens to each other”, “everyone cooperates”, and “everyone shares their knowledge”, together with rules concerning high-quality helping behavior like “ask precise questions” and “give help when needed”, were practiced and written on a poster (Oortwijn et al. 2008a, b). This poster was displayed in the classroom and remained there throughout the curriculum as a memory aid for the students. In addition, video fragments were shown in which two actors demonstrated both the correct and incorrect application of each rule. After two training lessons, students worked in groups on authentic assignments adapted from the regular mathematics curriculum. Their teacher supported students during the cooperative group work. Student cooperation was videotaped during two out of nine 1-h lessons. Students filled out the posttest at the end of the curriculum.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Because our study concerned individual students working in groups (Hox 2010), multilevel analysis was conducted to examine which types of students’ helping behavior enhance mathematics performance. Even though our sample was relatively small, it was large enough to estimate the final model. Because we were primarily interested in utterances exchanged during peer interaction, all intervening teacher utterances were removed from the analysis. Students’ absolute numbers of each type of helping behavior were added as student-level predictors. Converting the number of utterances into percentages would inevitably violate the assumption of (multi)collinearity, and produces inflated error term-sizes (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). The variable ‘number of contributions’ was included to control for variance between students. Extreme positive skewness was noted for three variables (apply answer, give explanation, and process regulation), as five students disproportionally often engaged in (either one of) these behaviors. After applying a square root transformation on all helping behavior variables and excluding the cooperative behaviors of these five outliers, the assumption of normality was met. It should be noted that these five students were all allocated to different groups, and the decision not to include their behavioral data did not result in loss of data on the group level.

Both mathematics achievement and verbal interaction are confounded with gender (Chizhik 2001). Therefore, we controlled for gender and the pretest scores (CITO mathematics test) by adding them as student-level predictors. Ethnicity was also added as a predictor at the lowest level. Table 2 depicts the summary statistics of all student-level variables included. At the group level, the dummy variable group composition was added. By distinguishing between ethnically heterogeneous (i.e., students of native and non-native origin) and ethnically homogeneous groups (i.e., all students with non-native backgrounds), we examined whether participating in heterogeneously composed groups positively affected individual mathematics achievement. In addition to the multilevel analysis, a MANOVA was performed to test whether ethnically heterogeneous and homogenous groups differed in the quality of helping behavior they used during group work.

3 Results

3.1 Research question 1: types of helping behavior as predictors of mathematics performance

First, a multilevel analysis was performed to examine the relation between types of student helping behavior and individual mathematics performance. The estimates of variance in the intercept-only model are presented in Table 3, column Model 1. The corresponding intra-class correlation indicated an unexplained variation at the second level of 32.89% among students on their posttest scores, and supported the use of multilevel analysis. A full model comprising all first- and second-level predictors fitted the data significantly better compared to the intercept-only model, χ2(14) = 251.24, p < .01. Although the full model (Model 2) provided a good fit to the data, a stepwise deletion was performed to generate a model that included only significant predictors. The final model (Model 3) fits the data equally well as the full model (Model 2), χ2(6) = 1.98, p > .05. Following the parsimony principle, the simpler model (Model 3) is preferred. Model 3 explained 38.89% of the total variance in students’ mathematics achievement scores on the posttest.

The significant intercept in Table 3 predicts, when controlling for all other variables, a value of 4.91 for the mathematics posttest. Further examination of Table 3 shows that, on average, higher scores on the pretest bring about a 0.13 point increase in posttest scores. Students who on average gave more answers scored 0.38 points higher on the posttest. Likewise, students who more frequently used process regulation scored 0.34 points higher. However, the negative regression coefficient for ‘number of contributions’ implies a 0.02 decrease of posttest scores when students contributed more. Similarly, with each scale point higher on both giving and applying explanations, the posttest score is expected to decrease by 0.35 and 0.85 scale points, respectively.

3.2 Research question 2: ethnic background and group composition as predictors of mathematics performance

With this same multilevel model, presented in Table 3, we also tested whether mathematical learning gains vary (a) for students of native and non-native origin and (b) for groups with a multi-ethnic heterogeneous or homogeneous composition. The regression coefficient for ethnicity at the individual level indicates that, compared to students of native origin, students with non-native backgrounds on average scored 1.19 points lower on the posttest. Furthermore, we tested whether the mathematical learning gains vary for students working in heterogeneous or homogeneous groups. Results show that working in an ethnically heterogeneous group yields an increase of 1.80 in the posttest scores, as compared to groups in which only students of non-native origin cooperated.

3.3 Research question 3: quality of helping behavior in ethnically heterogeneous and homogeneous groups

A MANOVA was performed to test whether ethnically heterogeneous and homogenous groups differed in the quality of helping behavior they used during group work. To this end, student’s absolute frequencies in which they used a certain type of helping behavior were merged, resulting in an absolute group frequency.

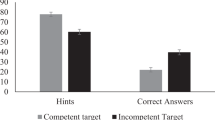

There was a significant difference in the types of helping behavior used based on group composition, F(1, 81) = 14.14, p < .001; Wilk’s Λ = 0.36, η 2p = .64. As can be seen in Table 4, group composition had a statistically significant effect on the frequency in which groups gave explanations, F(1, 90) = 6.27, p = .014, η 2p = .07, gave non-elaborate answers, F(1, 90) = 4.89, p = .03, η 2p = .05, and engaged in individual (process related) task-oriented behavior, F(1, 90) = 19.62, p < .001, η 2p = .18. The mean scores in Table 4 show that ethnically heterogeneous groups less often gave high-quality explanations when compared to homogeneous groups, and is considered a medium-sized effect (Cohen 1988). Heterogeneous groups used low quality helping behavior in the form of giving non-elaborate answers more often than homogeneous groups. This is a small effect (Cohen 1988). Homogeneous groups more often engaged in task-oriented behaviors related to students’ individual processes (e.g., utterances indicating students are thinking aloud while working on parts of the assignment individually), and can be considered a large effect (Cohen 1988). The groups did not differ in terms of all other types of helping behavior presented in Table 4.

4 Discussion

The first general aim of this study was to examine which types of students’ helping behavior enhance mathematical learning gains. We expected that high-quality helping behavior would predict higher posttest scores, whereas low-quality helping behavior would negatively affect the posttest performance, and we expected that this would apply to both students of native and those of non-native origin. Regarding high-quality behaviors, the only positive relation was found between process regulation and the posttest scores. This is in line with recent studies on team regulation of social activities and group processes, both of which can lead to better learning results (e.g., Janssen et al. 2012; Saab 2012). Hadwin and Oshige (2011) argue that sharing the responsibility of monitoring, evaluating, and regulation of the task process eases the cognitive demands of completing the task and facilitates learning.

However, in contrast to previous studies (e.g., Gillies and Khan 2008), a significant negative relation was found between the posttest scores and giving explanations. The high-quality helping behavior of asking for elaborate explanations did not significantly predict posttest scores. Similarly, the previously reported relation between applying explanations and mathematical posttest scores (e.g., Webb and Mastergeorge 2003) was not corroborated by our findings. This implies that asking for and applying high-quality helping behavior does not improve mathematical performance, whereas giving explanations can result in lower mathematical achievement.

In addition, the data from our study suggest that effective helping behavior (i.e., types of behavior positively predicting mathematics performance) cannot always be equated with high-quality helping behavior. Contrary to our expectations and previous research, we found that low-quality helping behavior in the form of giving answers is beneficial for the learning process as it positively predicts mathematics performance. Whereas it is widely acknowledged that low-quality answers are less beneficial for the help receiver (e.g., Webb and Mastergeorge 2003), the current study adds to previous works by examining this effect from the perspective of the help giver. From this perspective, being able to give correct answers can reflect a good understanding of the subject matter.

One explanation for these findings could be that without some external guidance, students do not give elaborate explanations, ask stimulating questions, or use relevant prior knowledge (Gillies and Khan 2008; Webb et al. 2006). In our study, the teachers trained the students to cooperate effectively and intervened during group work if students did not follow the cooperative learning ground rules. Even though all students engaged in some form of high-quality helping behavior during group work, it may be that especially the students of non-native origin needed more external modeling in order to fully engage in effective high-quality helping behaviors that are thought to promote mathematical learning gains. For example, Webb and Farivar (1994) found that, when placed in an experimental condition in which structured high-quality teacher stimulation was given, students with non-native backgrounds benefitted substantially from high-quality teacher stimulation and outperformed the students of non-native origin in the control condition who only received basic communication skills training.

Another explanation for our findings (i.e., a positive relation between giving answers and the posttest scores and the non-corroborated effect of all high-quality helping behaviors) could be that process regulation served as some sort of a compensation for some low- (i.e., giving answers) and high-quality (i.e., giving explanations) helping behaviors. Our results show that students who engaged in planning, monitoring, and evaluating behaviors on average scored higher on the posttest. In addition, a post hoc analysis showed a positive correlation between process regulation and giving explanations (r = .65, p < .001), and between process regulation and giving answers (r = .30, p = .008). This could imply that merely giving answers incites a peer’s high-quality helping behavior in the form of process regulation, which at its turn may boost individual mathematics performance.

The second question in this study sought to determine whether mathematics performance varies for (a) students of native and non-native origin and (b) for groups with an ethnically heterogeneous or homogeneous (i.e., all non-native) composition. The results from the multilevel analysis indicate a difference regarding the role of ethnicity in mathematics achievement when included at the student- and the group-level. At the student-level, a significant negative relation between ethnicity and the mathematics posttest scores was found. Students of native origin performed better on the mathematics posttest than students of non-native origin. This is in line with other studies reporting non-native students’ lower performance on contextualized mathematics (e.g., Hickendorff 2013b).

In our study, students with slightly different mathematical competence levels worked in groups of three to four. Cohen (1994) and Gillies and Haynes (2011) have shown that this method may be conducive to students’ learning process. Our study is one of the first to show that when heterogeneous ethnic group composition is modeled as a group-level predictor, it can positively predict mathematics performance. The key finding of this study is that working in heterogeneous groups based on ethnic backgrounds also can be beneficial for learning, for both students of native and non-native origin. Working together with students of native origin with higher levels of Dutch proficiency possibly helped students with non-native backgrounds to overcome difficulties in understanding the meaning of word problems in realistic mathematics education (e.g., Hickendorff 2013a, b). The conceptual rewording of mathematical word problems may have facilitated understanding and subsequent performance (Vicente, Orrantia, and Verschaffel 2007).

Our third question addressed whether ethnically heterogeneous groups used more high-quality helping behaviors as compared to homogeneous groups. We found that heterogeneous and homogeneous groups indeed differed in the types of helping behavior used. Interestingly, even though the multilevel analysis showed that working in heterogeneous groups is beneficial for mathematics performance, this finding cannot be attributed to more frequent use of (a specific type of) high-quality helping behavior. On the contrary: We found that homogeneous rather than heterogeneous groups more often engaged in high-quality helping behavior in the form of giving explanations. Heterogeneous groups gave more answers (i.e., low-quality helping behavior) than homogenous groups. Even though the results must be interpreted with some caution given the small-to-medium-sized effects, the reported differences between heterogeneous and homogeneous groups in terms of the quality and types of helping behavior might explain why working in a homogeneous group is less beneficial for individual mathematics learning. After all, the results of our study indicate that giving explanations can in fact negatively predict mathematics scores.

The results of this study do not support our initial hypothesis that higher proficiency levels of the Dutch language enable students of native origin to take on a tutor role and to engage in high-quality helping behaviors. Instead, we found that students in heterogeneous groups more often give non-elaborate answers (i.e., low-quality helping behavior) than students in homogeneous groups. When retrospectively examining the utterances we have categorized as giving non-elaborate answers, it seems that students of native origin in heterogeneous groups helped group members with non-native backgrounds by making contextual problems more understandable. They conceptually rephrased the contextual problems, simplified the problem-solving strategy, and focused on relevant aspects of the problem. For instance, when a student of non-native origin asked for an explanation, one of her peers of native origin replied by explicitly mentioning the strategy (“It is length times width.”), pointed out which numbers she should use, and wrote down the equation for her. It could be that the help giver was well aware that a more elaborate explanation might have proven to be too difficult for the student of non-native origin and instead broke the strategy down by rephrasing it into easy-to-comprehend chunks of information. Behaviors such as conceptually rephrasing contextual problems could, therefore, also be considered as a specific type of high-quality helping behavior, as this could positively affect individual mathematics performance (Vicente et al. 2007).

The last finding is that, when compared to heterogeneous groups, ethnically homogeneous groups more often engaged in task-oriented behaviors related to students’ individual processes such as thinking and counting out loud and evaluating individual difficulties. Even though this type of individual-level regulative behavior was not a significant predictor of mathematics performance (in contrast to regulation of processes at the group level), it is possible that process regulation on the individual level also positively contributes to effective cooperative learning, albeit in an indirect manner. Interaction processes underlying engagement and effective cooperative learning are continuously regulated at both the individual and social (i.e., group) level. The articulation of regulation of individual students’ processes possibly helped other group members to regulate their processes as students change the contexts and groups in which they regulate their motivation, cognition, and behaviors (Hadwin et al. 2011).

4.1 Limitations

Even though teachers filled out self-reports to indicate to what extent they had implemented the ground rules (see Oortwijn et al. 2008a, b), this provided limited insight into how teachers actually intervened (i.e., what they said during group work) and whether this intervention actually was in line with the ground rules and the intended high-quality helping behavior. Another limitation of this study is that we did not examine sequences of interactions (i.e., examine which type of helping behavior is followed by what response). Future studies using sequential analysis (see Jeong 2005) may offer an additional perspective and help interpreting our findings. For example, a sequential analysis would enable us to examine which types of helping behavior are often followed by process regulation, which our analyses pinpointed as a positive predictor of students’ mathematics performance.

4.2 Conclusions

The message emphasized by this study is simple but important: The widely acknowledged potential of cooperative learning is not only inextricably interwoven with the quality of helping behavior but also with multi-ethnic group composition. The implications for everyday classroom practice are twofold. First, our results suggest that teachers should not underestimate the importance of instructing their students to regulate their peers’ learning processes, offer explanations, give answers, and rephrase contextual problems. Teachers should model these behaviors during classroom instruction and stimulate them during group work. Second, it is recommended to take into account the ethnic composition of groups, because working in ethnically heterogeneous groups can be conducive to learning for both students of native and non-native origin. The findings of this study suggest the importance of making sure groups are not only heterogeneously composed regarding mathematics performance level but also regarding ethnicity and language proficiency.

References

Abedi, J., & Lord, C. (2001). The language factor in mathematics tests. Applied Measurement in Education, 14, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324818AME1403_2.

Bradby, D. (1992). Language characteristics and academic achievement: A look at Asian and Hispanic eighth graders in NELS: 88. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Chizhik, A. W. (2001). Equity and status in group collaboration: Learning through explanations depends on task characteristics. Social Psychology of Education, 5, 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014405118351.

Cohen, E. G. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Review of Educational Research, 64, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543064001001.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Di Bartolomeo, A. (2011). Explaining the gap in educational achievement between second-generation immigrants and natives: The Italian case. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 16, 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2011.593749.

Erkens, G. (2005). Multiple episode protocol analysis (version 4.10) [Computer software]. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Evers, A., Van Vliet-Mulder, J. C., & Groot, C. J. (2000). COTAN documentatie van tests en test research in Nederland [COTAN documentation on tests and test research in the Netherlands]. Amsterdam: Boom Test Publishers.

Freudenthal, H. (1973). Mathematics as an educational task. Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company.

Gillies, R. M. (2006). Teachers’ and students’ verbal behaviours during cooperative and small-group learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X52337.

Gillies, R. M., & Haynes, M. (2011). Increasing explanatory behaviour, problem-solving, and reasoning within classes using cooperative group work. Instructional Science, 39, 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-010-9130-9.

Gillies, R. M., & Khan, A. (2008). The effects of teacher discourse on students’ discourse, problem-solving and reasoning during cooperative learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 47, 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2008.06.001.

Hadwin, A. F., Järvelä, S., & Miller, M. (2011). Self-regulated, co-regulated, and socially shared regulation of learning. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 65–84). New York, NY: Routledge Falmer.

Hadwin, A. F., & Oshige, M. (2011). Self-regulation, coregulation, and socially shared regulation: Exploring perspectives of social in self-regulated learning theory. Teachers College Record, 113, 240–264.

Hickendorff, M. (2013a). The effects of presenting multidigit mathematics problems in a realistic context on sixth graders’ problem solving. Cognition and Instruction, 31, 314–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2013.799167.

Hickendorff, M. (2013b). The language factor in elementary mathematics assessments: Computational skills and applied problem solving in a multidimensional IRT framework. Applied Measurement in Education, 26, 253–278.

Hox, J. J. (2010). Multilevel analysis. Techniques and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge Falmer.

Janssen, J., Erkens, G., Kirschner, P. A., & Kanselaar, G. (2012). Task-related and social regulation during online collaborative learning. Metacognition and Learning, 7, 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-010-9061-5.

Jeong, A. (2005). A guide to analyzing message-response sequences and group interaction patterns in computer-mediated communication. Distance Education, 26, 367–383.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational Researcher, 38, 365–379. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09339057.

Karssen, M., Van der Veen, I., & Volman, M. (2017). Diversity among Bi-ethnic students and differences in educational outcomes and social functioning. Social Psychology of Education, 20, 753–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9394-x.

Kieffer, M. J. (2008). Catching up or falling behind? Initial English proficiency, concentrated poverty, and the reading growth of language minority learners in the United States. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 851–868. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.4.851.

Kilpatrick, J., Swafford, J., & Findell, B. (2001). Adding it up. Helping children learn mathematics. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

King, A. (2002). Structuring peer interaction to promote high-level cognitive processing. Theory into Practice, 41, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4101_6.

Nelson-Le Gall, S. (1992). Children’s instrumental help-seeking: Its role in the social acquisition and construction of knowledge. In R. Hertz-Lazarowitz & N. Miller (Eds.), Interaction in cooperative groups: The theoretical anatomy of group learning (pp. 49–68). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Norenes, S. O., & Ludvigsen, S. (2016). Language use and participation in discourse in the mathematics classroom: When students write together at an online website. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 11, 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2016.05.003.

OECD. (2010). PISA 2009 results: What students know and can do. Student performance in reading, mathematics and science (Vol. I). Paris: OECD.

Oortwijn, M. B., Boekaerts, M., & Vedder, P. (2005). Is coöperatief rekenen op multiculturele basisscholen effectiever dan klassikaal leren? [Is cooperative learning during mathematics at multi-ethnic elementary schools more effective than direct teaching?]. Panama-Post, 24(4), 3–11.

Oortwijn, M. B., Boekaerts, M., & Vedder, P. (2008a). The impact of the teacher’s role and pupils’ ethnicity and prior knowledge on pupils’ performance and motivation to cooperate. Instructional Science, 36, 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9032-7.

Oortwijn, M. B., Boekaerts, M., Vedder, P., & Strijbos, J.-W. (2008b). Helping behaviour during cooperative learning and learning gains: The role of the teacher and of pupils’ prior knowledge and ethnic background. Learning and Instruction, 18, 146–159.

Roscoe, R. D., & Chi, M. T. H. (2007). Understanding tutor learning: Knowledge-building and knowledge-telling in peer-tutors’ explanations and questions. Review of Educational Research, 77, 534–574. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307309920.

Saab, N. (2012). Team regulation, regulation of social activities or co-regulation: Different labels for effective regulation of learning in CSCL. Metacognition and Learning, 7, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-011-9085-5.

Schönwälder, K. (2007). Residential segregation and the integration of immigrants: Britain, the Netherlands and Sweden (WZB discussion paper, no. SP IV 2007-602). Retrieved from: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/49762. Accessed 21 Sept 2017.

Statistics Netherlands. (2003). In 2020 een op de drie leerlingen allochtoon [In 2020, one in every three students is non-native]. Retrieved from: http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/bevolking/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2003/2003-1164-wm.htm. Accessed 13 May 2016.

Strijbos, J. W., Martens, R. L., Prins, F. J., & Jochems, W. M. (2006). Content analysis: What are they talking about? Computers & Education, 46, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.04.002.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

United States Government Accountability Office. (2016). K-12 education: Better use of information could help agencies identify disparities and address racial discrimination (GAO-16-345). Retrieved from: http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676745.pdf. Accessed 21 Sept 2017.

Vedder, P. (1985). Cooperative learning. A study on processes and effects of cooperation between primary school children. Groningen: University of Groningen.

Vicente, S., Orrantia, J., & Verschaffel, L. (2007). Influence of situational and conceptual rewording on word problem solving. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 829–848. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709907X178200.

Walzebug, A. (2014). Is there a language-based social disadvantage in solving mathematical items? Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 3, 159–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.03.002.

Webb, N. M. (2009). The teacher’s role in promoting collaborative dialogue in the classroom. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X380772.

Webb, N. M., & Farivar, S. H. (1994). Promoting helping behavior in cooperative small groups in middle school mathematics. American Educational Research Journal, 31, 369–395.

Webb, N. M., Farivar, S. H., & Mastergeorge, A. M. (2002). Productive helping in cooperative groups. Theory into Practice, 41, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4101_3.

Webb, N. M., & Mastergeorge, A. M. (2003). The development of students’ learning in peer directed small groups. Cognition and Instruction, 21, 361–428. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci2104_2.

Webb, N. M., Nemer, K. M., & Ing, M. (2006). Small group reflections: Parallels between teacher discourse and student behaviour in peer-directed groups. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15, 63–119. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1501_8.

Zakaria, E., Chin, L. C., & Daud, Y. (2010). The effects of cooperative learning on students’ mathematics achievement and attitude towards mathematics. Journal of Social Sciences, 6, 272–275. https://doi.org/10.3844/jssp.2010.272.275.

Zhan, C. (2015). School and neighborhood: Residential location choice of immigrant parents in the Los Angeles Metropolitan area. Journal of Population Economics, 28, 737–783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-015-0545-0.

Acknowledgements

First, we thankfully acknowledge the work of Michiel Oortwijn on which this article is based. Michiel passed away in 2010. In addition, we thank Martijn Klitsie for his advice in revising the coding scheme and assistance in coding and Frank Kuipers for his helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in line with the ethical research guidelines of, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the center for Education and Child Studies at Leiden University and the Institutional Review Board of the Interuniversity Graduate School for the Study of Education and Human Development (ISED).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mouw, J.M., Saab, N., Janssen, J. et al. Quality of group interaction, ethnic group composition, and individual mathematical learning gains. Soc Psychol Educ 22, 383–403 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09482-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09482-w