Abstract

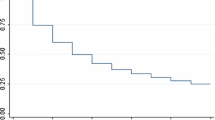

The pre-exiting productivity profile of mature firms relative to survivors is examined along with an evaluation of how productivity affects the probability of exit along various dimensions. An empirical approach, based on an unbalanced panel of Portuguese manufacturing firms covering a 10-year period, is used. The findings confirm that market selection forces low-productivity firms to exit, but there is also evidence that a sizeable portion of low-productivity firms do not shut down. Conversely, there is a non-negligible fraction of high-productivity firms that do actually close. Consistent with some key theoretical predictions, our analysis reveals that exiting firms have a falling productivity level over a number of years prior to exit. Finally, the results from the survival model show that both small firms and ones with low productivity are relatively much more likely to exit the market. Industry and macro-environment are also found to have a non-negligible role on the exit of mature firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Most empirical studies point to firms achieving the mature state somewhere between the sixth and tenth year of existence. In our dataset, the results from using an alternative threshold (e.g. 8 years) are virtually the same as the ones reported in Sect. 4.

As pointed out by Headd (2003) and van Praag (2003), it would be preferable to distinguish voluntary from involuntary closures, but unfortunately (see Sect. 3.2) this distinction is not possible in our dataset. This limitation is present in virtually all empirical studies in the literature, with a few exceptions (e.g. Harada 2007).

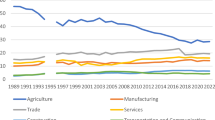

The aggregate results for the entire Portuguese manufacturing sector were also weighted. We note that Região Centro represents approximately one-seventh of the Portuguese gross domestic product and one-sixth of total employment. Either in terms of employment or output, the shares of each one of the 17 sub-sectors in the manufacturing aggregate at the national and Região Centro level are virtually the same, with the observed differences in 2000, for example, never exceeding 6% points.

We note that the observation of exit is constrained by the characteristics of the IEH survey. Thus, in our dataset exit comprises bankruptcy and voluntary closure as well as the residual category of mergers/acquisitions, a rare and negligible event which according to Mata and Portugal (2002, 2004) does not exceed 1% of the total number of closures. A change in the sector of activity in turn is taken as diversification, not as an exit. All firms younger than 10 years were dropped from our sample.

Right-censoring in our dataset is due to panel rotation, on the one hand, and to firm’s survival (i.e. survival after 2000), on the other. Since all firms in our sample started production some time (at least 10 years) before the beginning of the survey, the dataset is also left-censored. This is not a problem as our focus lies on the conditional probability of exit based on calendar time.

This model was also implemented by Mata and Portugal (2002).

There was an overall slowdown in 1991–1994, followed by a clear economic recovery which in the last sub-period (1997–2000) seemed to have lost some momentum (Carreira and Teixeira 2008).

Estimation was performed using the stcox command with the efron and shared options of StataSE 9.2. The strata (industry) option was not implemented given that the productivity level of exiting firms was normalized by the average productivity of survivors at the industry level. The null hypothesis of no unobserved heterogeneity was not rejected.

Two explanations for the low (negative) correlation between GDP growth and unemployment are possible: the first one is associated to a wide lag between job creation and the economic cycle observed in the Portuguese economy (e.g. Baptista and Thurik 2007); the second is related to the intense restructuring wave observed in the middle of the 1990s in the Portuguese manufacturing sector (Carreira and Teixeira 2008).

The robustness of the results reported in Table 9 was analysed in the context of the PWCH model. The results from this model (available from the authors upon request) are virtually the same.

References

Ahn, S. (2001). Firm dynamics and productivity growth: A review of micro evidence from OECD countries. Economics Department Working Papers no. 297. Paris: OECD.

Almus, M. (2004). The shadow of death: An empirical analysis of the pre-exit performance of new German firms. Small Business Economics, 23(3), 189–201.

Asplund, M., & Nocke, V. (2003). Imperfect competition, market size and firm turnover. CEPR. Discussion Paper DP 2625. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Audretsch, D. B. (1994). Business survival and the decision to exit. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 1(1), 125–137.

Audretsch, D. B. (1995a). Innovation, growth and survival. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 441–457.

Audretsch, D. B. (1995b). Innovation and industry evolution. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Audretsch, D. B., & Mahmood, T. (1994). The rate of hazard confronting new firms and plants in US manufacturing. Review of Industrial Organization, 9(1), 41–56.

Audretsch, D. B., & Mahmood, T. (1995). New firm survival: New results using a hazard function. Review of Economics and Statistics, 77(1), 97–103.

Audretsch, D. B., & Mata, J. (1995). The post-entry performance of firms: Introduction. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 413–419.

Baily, M. N., Hulten, C. R., & Campbell, D. (1992). Productivity dynamics in manufacturing plants. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Microeconomics, 1992, 187–249.

Baldwin, J. R. (1995). The dynamics of industrial competition: A North American perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baptista, R., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). The relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment: Is Portugal an outlier? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 74(1), 75–89.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Bates, T. (2005). Analysis of young, small firms that have closed: Delineating successful from unsuccessful closures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(3), 343–358.

Baum, J. A. (1989). Liabilities of newness, adolescence, and obsolescence: Exploring age dependence in the dissolution of organizational relationships and organizations. Proceedings of the Administrative Science Association of Canada, 10, 1–10.

Bellone, F., Musso, P., Nesta, L., & Quéré, M. (2006). Productivity and market selection of French manufacturing firms in the nineties. Revue de L’OFCE, 0(Special Issue), 319–349.

Box, M. (2008). The death of firms: Exploring the effects of environment and birth cohort on firm survival in Sweden. Small Business Economics, 31(4), 379–393.

Cabral, L. (1995). Sunk costs, firm size and firm growth. Journal of Industrial Economics, 43(2), 161–172.

Cabral, L., & Mata, J. (2003). On the evolution of the firm size distribution: Facts and theory. American Economic Review, 93, 1075–1090.

Carreira, C. (2006). Dinâmica industrial e crescimento da produtividade. Oeiras: Celta Editora.

Carreira, C., & Teixeira, P. (2008). Internal and external restructuring over the cycle: A firm-based analysis of gross flows and productivity growth in Portugal. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 29(3), 211–220.

Caves, R. (1998). Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(4), 1947–1982.

Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 34(2), 187–220.

Cox, D. R., & Oakes, D. (1984). Analysis of survival data. London: Chapman & Hall.

Disney, R., Haskel, J., & Heden, Y. (2003a). Restructuring and productivity growth in UK manufacturing. Economic Journal, 113(489), 666–694.

Disney, R., Haskel, J., & Heden, Y. (2003b). Entry, exit and establishment survival in UK manufacturing. Journal of Industrial Economics, 51(1), 91–112.

Doms, M., Dunne, T., & Roberts, M. J. (1995). The role of technology use in the survival and growth of manufacturing plants. Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 523–542.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M. J., & Samuelson, L. (1989). The growth and failure of U.S. manufacturing plants. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 671–698.

Efron, B. (1977). The efficiency of Cox’s likelihood function for censored data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 72, 557–565.

Ericson, R., & Pakes, A. (1995). Markov-perfect industry dynamics: A framework for empirical work. Review of Economics Studies, 62(1), 53–82.

Esteve-Pérez, S., Llopis, A. S., & Llopis, J. A. (2004). The determinants of survival of Spanish manufacturing firms. Review of Industrial Organization, 25(3), 251–273.

Esteve-Pérez, S., & Mañez-Castillejo, J. A. (2008). The resource-based theory of the firm and firm survival. Small Business Economics, 30(3), 231–249.

Esteve-Pérez, S., Mañez-Castillejo, J. A., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2008). Does a “survival-by-exporting” effect for SMEs exist? Empirica, 35(1), 81–104.

Evans, D., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808–827.

Fertala, N. (2008). The shadow of death: Do regional differences matter for firm survival across native and immigrant entrepreneurs? Empirica, 35(1), 59–80.

Fotopoulos, G., & Louri, H. (2000). Determinants of hazard confronting new entry: Does financial structure matter? Review of Industrial Organization, 17(3), 285–300.

Geroski, P. A. (1995). What do we know about entry? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 421–440.

Geroski, P. A., Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2007). Founding conditions and the survival of new firms. Working Paper No. 07-11. Aalborg: DRUID.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T., Cooper, A., & Woo, C. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 750–783.

Griliches, Z., & Regev, H. (1995). Firm productivity in Israeli industry: 1979-1988. Journal of Econometrics, 65(1), 175–203.

Haltiwanger, J. C., Lane, J. I., & Spletzer, J. R. (2007). Wages, productivity, and the dynamic interaction of businesses and workers. Labour Economics, 14(3), 575–602.

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to selfemployment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631.

Hannan, M. T. (1998). Rethinking age dependence in organizational mortality: Logical formalizations. American Journal of Sociology, 104(1), 126–164.

Hannan, M. T. (2005). Ecologies of organizations: Diversity and identity. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 51–70.

Harada, N. (2007). Which firms exit and why? An analysis of small firm exits in Japan. Small Business Economics, 29(4), 401–414.

Headd, B. (2003). Redefining business success: Distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 51–61.

Hopenhayn, H. (1992). Entry, exit, and firm dynamics in long run equilibrium. Econometrica, 60(5), 1127–1150.

Hopenhayn, H., & Rogerson, R. (1993). Job turnover and policy evaluation: A general equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 101(5), 915–938.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670.

Manjón-Antolín, M. C., & Arauzo-Carod, J. M. (2008). Firm survival: Methods and evidence. Empirica, 35(1), 1–24.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (1994). Life duration of new firms. Journal of Industrial Economics, 42(3), 227–245.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2002). The survival of new domestic and foreign owned firms. Strategic Management Journal, 23(4), 323–343.

Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2004). Patterns of entry, post-entry growth and survival. Small Business Economics, 22(3–4), 283–298.

Mata, J., Portugal, P., & Guimarães, P. (1995). The survival of new plants: Start-up conditions and post-entry evolution. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 459–481.

Morton, F. M., & Podolny, J. M. (2002). Love or money? The effects of owner motivation in the California wine industry. Journal of Industrial Economics, 50(4), 431–456.

Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2005). STAN indicators. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/3/33/40230754.pdf

Oliveira, B., & Fortunato, A. (2006). Firm growth and liquidity constraints: A dynamic analysis. Small Business Economics, 27(2–3), 139–156.

Pakes, A., & Ericson, R. (1998). Empirical implications of alternative models of firm dynamics. Journal of Economic Theory, 79(1), 1–45.

Saridakis, G., Mole, K., & Storey, D. J. (2008). New small firm survival in England. Empirica, 35(1), 25–39.

Strotmann, H. (2007). Entrepreneurial survival. Small Business Economics, 28(1), 87–104.

Taylor, M. (1999). Survival of the fittest? An analysis of self-employment duration in Britain. Economic Journal, 109(454), C140–C155.

Troske, K. R. (1996). The dynamic adjustment process of firm entry and exit in manufacturing and finance, insurance, and real estate. Journal of Law and Economics, 39(2), 705–735.

van den Berg, G. J. (2001). Duration models: Specification, identification, and multiple durations. In J. J. Heckman & E. Leamer (Eds.), Handbook of econometrics (Vol. 5, pp. 3381–3460). North Holland: Amsterdam.

van Praag, C. M. (2003). Business survival and success of young small business owners. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 1–17.

Wagner, J. (1999). The life history of cohorts of exits from German manufacturing. Small Business Economics, 13(1), 71–79.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous referees for their most helpful comments on the previous version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carreira, C., Teixeira, P. The shadow of death: analysing the pre-exit productivity of Portuguese manufacturing firms. Small Bus Econ 36, 337–351 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9221-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9221-7