Abstract

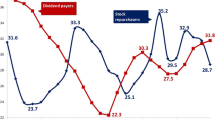

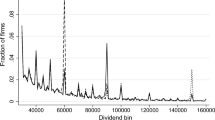

The main purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of the integrated tax system introduced in Taiwan on the valuation of dividends. Based on Elton and Gruber’s (Rev Econ Stat 52:68–74, 1970) model, the ratio of ex-day price drop to cash dividend per share (i.e., the drop-off ratio) should reflect the relative taxes on dividends and capital gains. In Taiwan, the suspension of capital gains taxes, the coexistence of taxable and non-taxable stock dividends, and the change in tick sizes allow us to control for the influences of non-tax factors on drop-off ratios. In this paper, we find significant increases in drop-off ratios for both cash dividends and taxable stock dividends after Taiwan’s tax reform (in 1998), while we find no significant changes in drop-off ratios for non-taxable stock dividends. These results provide further evidence to support the argument that tax affects the valuation of firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Taiwan, the tax rate for corporate income below NT$100,000 (about $3,000 U.S. dollar) is 15%, and that above NT$100,000 is 25%. Since it is seldom for firms making profits below NT$100,000, it is appropriate to conclude that corporate income is subject essentially a single rate of 25%.

A noteworthy feature of the new integrated tax system is that for individual shareholders whose dividend tax payables are lower than their tax credits, the remaining credits are fully refundable.

For all stocks priced above one dollar per share on the Taiwan Stock Exchange, the tick size is never more than one percent of the stock’s price. For stocks priced below one dollar (so-called penny stocks), the tick size grows above one percent as the stock’s price declines below one dollar. The rising tick size percentage on penny stocks appears to exist to discourage the existence of such stocks. Since no penny stocks were included in our sample, the tick sizes were all less than one percent, and thus represent no statistical problems of the type suggested by Bali-Hite (1998).

The Tax Clientele Effect assumes shareholders with higher marginal tax rates on dividends prefer to invest in firms that retain more of their profits, and thereby offer capital gains, while shareholders with lower marginal tax rates prefer to invest in firms that distribute a higher fraction of their profits as dividends. This assumption implies that the drop-off ratio increases with the dividend yield.

The following analysis shows that the drop-off ratio for stock dividends is not the same as that for cash dividends. Therefore, we have to analyze and empirically test them separately.

Domestic institutional investors include government entities, financial institutions (securities firms and banks), corporations, mutual funds, etc.

References

Bali R, Hite GL (1998) Ex-dividend day stock price behavior: discreteness or tax-induced clienteles? J Financ Econ 47:127–159

Bell L, Jenkinson T (2002) New evidence of the impact of dividend taxation and on the identity of the marginal investor. J Finance 57:1321–1346

Booth L, Johnston D (1984) The ex-dividend day behavior of Canadian stock prices: tax change and clientele effects. J Finance 39:457–476

Brown P, Clarke A (1993) The ex-dividend day behavior of Australia share prices before and after dividend imputation. Aust J Manage 18:1–40

Chou RK, Lee WC, Chen SS (2005) The market reaction around ex-dates of stock splits before and after decimalization. Rev Pacific Basin Finan Markets Policies 8:201–216

Elton EJ, Gruber MJ (1970) Marginal stockholder tax rates and the clientele effect. Rev Econ Stat 52:68–74

Elton EJ, Gruber MJ, Blake CR (2005) Marginal stockholder tax effects and ex-dividend-day price behavior: evidence from taxable and non-taxable closed-end funds. Rev Econ Stat 87:579–586

Frank M, Jagannathan R (1998) Why do stock prices drop by less than the value of the dividend? Evidence from a country without taxes. J Financ Econ 47(2):161–188

Graham JR, Michaely R, Roberts MR (2003) Do price discreteness and transactions costs affect stock returns? Comparing ex-dividend pricing before and after decimalization. J Finance 58:2611–2635

Jakob K, Ma T (2004) Tick size, NYSE rule 118, and ex-dividend day stock price behavior. J Financ Econ 72:605–625

Jugurnath B, Stewart M, Brooks R (2008) Dividend taxation and corporate investment: a comparative study between the classical system and imputation system of dividend taxation in the United States and Australia. Rev Quant Financ Acc 31:209–224

Kadapakkam P (2000) Reduction of constraints on arbitrage trading and market efficiency: an examination of ex-day returns in Hong Kong after introduction of electronic settlement. J Finance 55:2841–2861

Kalay A (1982) The ex-dividend day behavior of stock prices: a re-examination of the clientele effect. J Finance 37:1059–1070

Lakonishok J, Vermaelen T (1983) Tax reform and ex-dividend day behavior. J Finance 38:1157–1179

Lamdin DJ (1993) Shareholder taxation and aggregate dividend payout: evidence from the tax reform act of 1986. Rev Quant Financ Acc 3:459–468

Lasfer MA (1995) Ex-day behavior: tax or short-term trading effects. J Finance 50:875–897

Lee YT, Liu YJ, Roll R, Subrahmanyam A (2006) Taxes and dividends clientele: evidence form trading and ownership structure. J Bank Finance 30:229–246

Michaely R (1991) Ex-dividend day stock price behavior: the case of the 1986 tax reform act. J Finance 47:845–859

Miller M, Modigliani F (1961) Dividend policy, growth and the valuation of shares. J Bus 34:411–433

Poterba J, Summers L (1984) New evidence that taxes affect the valuation of dividends. J Finance 39:1397–1415

White H (1980) A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48:817–838

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

In this appendix we show that under Taiwan’s tax system, which has no capital gains taxes, even though the short-term traders proposed by Kalay (1982) maybe present, the drop-off ratio will reflect the dividend taxes. In the U.S., short-term capital gains are taxed as ordinary income. Kalay agues that if the dividend per share is smaller than the expected price drop by more than transaction costs and taxes, investors can arbitrage by selling the stock short cum-dividend and buying it back ex-dividend; otherwise they can arbitrage by behaving in the opposite direction. The condition for no arbitrage opportunities to exist is:

where π0, the marginal tax rate on ordinary income and short-term capital gains for the arbitrager; τ · p, the expected transaction costs of a “round trip” (i.e., purchase and sale).

The definitions of P a and P b are given in Sect. 3. Since the capital gains tax rate is the same as that of the ordinary income, the influence of the tax rate can be factored out. Thus, the drop-off ratio (P b − P a )/D, derived from Eq. 6 reflects only the transaction costs. However, this is not the case in Taiwan since the capital gains taxes have been suspended. Therefore, the condition for no arbitrage opportunities to exist should be modified to be:

Rearranging, we get Eq. 8, as follows:

From Eq. 8, we know that even under the short-term trader hypothesis, the drop-off ratio in Taiwan will reflect the dividend tax rate π0. If the transaction costs and tick sizes are small enough, as argued in Kalay (1982), then the drop-off ratio will be close to (1 − π0), which is the same conclusion proposed by Elton and Gruber (1970).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Francis, J.C., Wu, T.Z.C. & Kuo, NT. Effects of tax reform on drop-off ratios and on the ex-dividend and ex-right prices. Rev Quant Finan Acc 39, 147–164 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-011-0246-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-011-0246-z