Abstract

Non-cooperative couples are inefficient. Cooperation raises the utility of both parents, and of each child, but does not guarantee efficiency. In the presence of credit rationing, a cooperative equilibrium may not exist outside marriage, because the main earner cannot credibly promise to compensate the main childcarer at some future date, and may not be able or willing to do so at front. By allowing the main childcarer to credibly threaten divorce if the main earner does not deliver the promised compensation when the time comes, marriage makes that promise credible, and thus increases the probability that a cooperative equilibrium will exist. In a separate-property jurisdiction, a reduction in the cost or difficulty of obtaining a divorce increases married women’s participation in the labour market. In a community-property one, it has no such effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The consequences of uncertainty about court decisions are examined in Deffains and Langlais (2006).

This formulation of the utility function implies that neither party cares about the other’s consumption. Allowing for mutual affection between f and m makes no qualitative difference to the results, so long as each party cares about its own consumption at least a little more than it cares for the other’s.

This assumption has some empirical justification. Burda et al. (2013) find that a person’s total (market plus domestic) work time varies across countries (notably, between Europe and the US), but not across households in the same country. What varies, within each country, is only the allocation of total work time between market and domestic activities.

The nonnegativity constraint on s i implies that that i can borrow only up to the capital endowment.

This constraint implies that the couple cannot borrow more than b f + b m .

That is the assumption in Lundberg and Pollak (1996), and many others in their wake. There, however, a NB equilibrium always exists, because the the CN equilibrium is always inside the UPF, and this symmetrical. We will how that this is typically not the case in our context.

If γ were prohibitively high, neither of these constraints would be binding, and the married equilibrium would thus coincide with the unmarried one, irrespective of credit conditions.

There is an assonance between this result and the one in Masters (2008), that it may be in the interest of the more attractive party to divest itself of some of its attractions in order to make the match stable.

Recall that, so long as t 0 is positive, there will be comparative advantages (in child care for the mother, in market work for the father) even if the parents have the same human capital endowments.

References

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Burda, M., Hamermesh, D., & Weil, P. (2013). Total work and gender: Facts and possible explanations. Journal of Population Economics, 26 (forthcoming).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2004). Women in the labor force: A databook. Washington DC: US Department of Labor.

Chiappori, P. A., Fortin, B., & Lacroix, G. (2002). Marriage market, divorce legislation, and household labor supply. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 37–72.

Chiappori, P. A., Iyigun, M., & Weiss, Y. (2009). Investment in schooling and the marriage market. American Economic Review, 99, 1689–1713.

Chiappori, P. A., & Oreffice, S. (2008). Birth control and female empowerment: An equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 113–140.

Chiappori, P. A., & Weiss Y. (2007). Divorce, remarriage, and child support. Journal of Labor Economics, 25, 37–74.

Cigno, A. (2007). A Theoretical Analysis of the Effects of Legislation on Marriage, Fertility, Domestic Division of Labour, and the Education of Children, CESifo WP 2143.

Clark, S. (1999). Law, property, and marital dissolution. Economic Journal, 109, C41–C54.

Deffains, B., & Langlais, E. (2006). Incentives to cooperate and the discretionary power of courts in divorce law. Review of Economics of the Household, 4, 423–439.

Del Boca, D., & Flinn, C. (1995). Rationalizing child support orders. American Economic Review, 85, 1241–1262.

Drago, R., Black, S., & Wooden, M. (2004). Female Breadwinner Families: Their Existence, Persistence and Sources, IZA DP 1308.

Ekert-Jaffe, O., & Grossbard, S. (2008). Does community property discourage unpartnered births? European Journal of Political Economy, 24, 25–40.

Gemici, A., & Laufer, S. (2010). Marriage and cohabitation. NYU mimeo.

Gray, J. S. (1998). Divorce law changes, household bargaining, and married women’s labor supply. American Economic Review, 88, 628–642.

Grossbard-Shechtman, A. (1982). A theory of marriage formality: The case of Guatemala. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 30, 813–830.

Iyigun, M. (2009). Marriage, Cohabitation and Commitment, IZA DP 4341.

Iyigun, M., & Walsh, R. P. (2007). Building the family nest: Premarital investments, marriage markets, and spousal allocations. Review of Economic Studies, 74, 507–535.

Konrad, K. A., & Lommerud, K. E. (2000). The bargaining family revisited. Canadian Journal of Economics, 33, 471–487.

Kunze, A. (2002). The Timing of Careers and Human Capital Depreciation, IZA DP 509.

Lam, D. (1988). Marriage markets and assortative mating with household public goods: Theoretical results and empirical implications. Journal of Human Resources, 23, 462–487.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (1996). Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 139–15.

Manning, J., & Petrongolo, B. (2008). The part-time pay penalty for women in Britain. Economic Journal, 118, F28–F51.

Masters, A. (2008). Marriage, commitment and divorce in a matching model with differential aging. Review of Economic Dynamics, 11, 614–628.

Mazzocco, M. (2007). Household intertemporal behaviour: A collective characterization and a test of commitment. Review of Economic Studies, 74, 857–895.

Mincer, J. & Ofek, H. (1982). Interrupted work careers: Depreciation and restoration of human capital. Journal of Human Resources, 17, 3–24.

Nordblom, K. (2004). Cohabitation and marriage in a risky world. Review of Economics of the Household, 2, 325–340.

Peters, M. & Siow, A. (2002). Competing premarital investments. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 592–608.

Rowthorn, R. (2002). Marriage as a signal. In A. Dnes & R. Rowthorn (Eds.), The law and economics of marriage and divorce. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Scott, E. (2002). Marital commitment and the legal regulation of divorce. In A. Dnes & R. Rowthorn (Eds.), The law and economics of marriage and divorce. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stancanelli, E. (2007). Marriage and Work: An Analysis for French Couples, OFCE Working Paper N° 207.

Stevenson, B. (2008). Divorce law and women’s labor supply. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 5, 853–873.

Vernon, V. (2010). Marriage: For Love, for money … and for time? Review of Economics of the Household, 8, 433–457.

Wickelgren, A. L. (2009). Why divorce laws matter: incentives for non-contractible marital investments under unilateral and consent divorce. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 25, 80–106.

Acknowledgments

Perceptive comments and suggestions by two anonimous referees, and editorial advice by Shoshana Grossbard, are gratefully acknowledged. Remaining errors are the author’s responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Efficiency

The first-order conditions yield

and

where μ is the Lagrange-multiplier of (10), necessarily positive, and ρ that of (11), positive if the couple is credit constrained, zero otherwise.

In view of (3, 4), and assuming that n is positive (or there would be no division of labour, and no gain from the union),

if \(\left( h_{f},h_{m}\right) \) satisfies (13), and the division of labour is consequently (14),

if \(\left( h_{f},h_{m}\right)\) violates (13), and the division of labour is then (15).

1.2 Cournot-Nash equilibrium

For i’s (i = f, m) first-order conditions on the choice of \(\left( a_{i1},a_{i2},s_{i},c_{i},t_{i}\right) , \)

and

where μ i is the Lagrange-multiplier of i’s period-2 budget constraint, and ρ i that of i’s credit constraint (i = f, m). Additionally, for f’s first-order condition on the choice of n,

Using (5, 6) and (40–42), we find that, at the CN equilibrium, a f1 = a m1, a f2 = a m2, μ f = μ m , ρ f = ρ m and U f = U m . As f could always choose n = 0, and thus L f = 1, the common utility level will be at least equal to U S. In view of (3–6) and (43), we also find that

where μ is now used to denote the common equilibrium value of μ f and μ m , and ρ that of ρ f and ρ m , at the CN equilibrium. This tells us that, if h f = h m and, consequently in view of (7), b f = b m , f and m will split everything down the middle. Otherwise, the monetary cost of the children will be divided equally between them, but the parent with the larger human capital endowment will supply more child care, and less market work, than the one with the larger money endowment. In other words, the parties will specialize against their comparative advantages.Footnote 12 The opportunity-cost of the children will not be minimized in either case.

The equilibrium will be inefficient, even if ρ = 0, because the MRS of t for c is equated to each parent’s, rather than to the couple’s, marginal opportunity-cost of providing attention, and that of n for v to the full cost of an extra child for f, rather than for the couple. As the full cost for the couple is inefficiently large, however, we cannot be sure that f’s share of this cost will be smaller than the efficient total. Therefore, we cannot say in general whether n will be too large or too small.

1.3 Nash-bargaining equilibrium without marriage

From the first-order conditions, we find that, at each point of the UPF,

and

where μ i is again the Lagrange-multiplier of i’s period-2 budget constraint, and ρ i that of i’s credit constraint (i = f, m). As cooperative parents specialize according to their personal comparative advantages, the signs of \(\frac{\partial L_{i}}{\partial t}\) and \(\frac{\partial L_{i}}{\partial n}\) are those shown in (38) if the initial endowments satisfy (??), or those shown in (39) if they do not. If ρ f = ρ m = 0, (44–46) reduce to (35–37), and the allocation is then efficient at every point of the UPF. Otherwise, f’s intertemporal trade-off, \(r+\frac{\rho _{f}}{\mu _{f}}, \) will be different from m’s, \(r+\frac{\rho _{m}}{\mu _{m}}. \) If that is the case, at some point or everywhere along the UPF, the allocation will be inefficient despite the fact that cooperative parents specialize according to their comparative advantages.

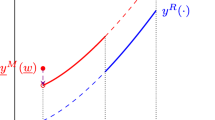

Let j denote the main childcarer, and k the main earner (j, k = f, m). As x 1 becomes larger (more positive if k = m, more negative if k = f), U j will rise relative to U k , but k’s credit ration will become tighter relative to j’s. In the case where

the allocation will then become more inefficient. As the opportunity-cost of U j in terms of U k increases faster than it would if k could either borrow, or postpone the payment, the UPF will be steeper than the efficiency locus, and lie inside it, everywhere in the \(\left( U_{j},U_{k}\right) \) plane. The case where

is more complicated. Up to the point where ρ k = ρ j , any increase in the size of x 1 will make the allocation less inefficient. The opportunity-cost of U j in terms of U k will then rise more slowly than it would if k were more tightly credit constrained than j, and the UPF will consequently be flatter than the efficiency locus, but still lie inside it. From that point onwards, we are back to the previous case. In view of (7) and (13) , \(\left( b_{k}-b_{j}\right) \) will be negative if k = f, but can have any sign if k = m. In the absence of any information about \(\left( b_{f},h_{f}\right) \) and \(\left( b_{m},h_{m}\right)\), other than that they satisfy (7), and given that \(\left(y_{k1}-y_{j1}\right) \) is positive anyway, the likelihood of (47) is then higher if we observe k = f, than if we observe k = m.

1.4 Nash-bargaining equilibrium with separate-property marriage

From the first-order conditions, we find that, at each point of the married UPF,

and

where ξ i denotes the Lagrange-multiplier of i’s divorce-threat constraint (i = f, m), and the other variables are defined as in the last section.

If neither divorce-threat constraint is binding (ξ f = ξ m = 0), these conditions reduce to (35–37), and the married UPF coincides with the unmarried one. Not so if either of these constraints is binding at some point. Given that only j’s divorce-threat constraint can be binding, k’s intertemporal trade-off remains \(\left( r+\frac{\rho _{k}}{\mu _{k}}\right) , \) but j’s becomes \(\left( r+\frac{\rho _{j}}{\mu _{j}-\xi _{j}}\right)\). In view of (28), ξ j ≥ 0 as U j ≤ U k . If (47) is true, the difference between k’s and j ’s intertemporal trade-offs is initially smaller, and the allocation less inefficient, than it would be without marriage. As x 1 becomes larger, however, ξ j decreases. Therefore, the married UPF is steeper than the unmarried one for all U j ≤ U k , and lies outside it for all U j < U k . By contrast, if (48) is true, the difference between the two trade-offs will be initially larger, and the allocation more inefficient, than it would be without marriage. As x 1 becomes larger, ξ j will again decrease, but the married UPF will now be flatter than the unmarried one for all U j ≤ U k . In either case, the married UPF will coincide with the unmarried one for all U j ≥ U k .

1.5 NB equilibrium with community-property marriage

For the first-order conditions, at each point of the married UPF,

and

where μ denotes the Lagrange-multiplier of the couple’s joint period-2 budget constraint, ρ that of their joint credit constraint, and ξ i that of i’s divorce-threat constraint, i = f, m. As only one of ξ f and ξ m can be positive, and irrespective of whether the credit constraint is or is not binding, an allocation will then be efficient if and only if neither divorce-threat constraint is binding.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cigno, A. Marriage as a commitment device. Rev Econ Household 10, 193–213 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-012-9141-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-012-9141-1

Keywords

- Gender

- Children

- Marriage

- Separate property

- Community property

- Divorce

- Married women’s labour participation