Abstract

This paper considers the effect of spouse’s characteristics on time devoted to leisure, child caregiving, and home production of married mothers and fathers using the American Time Use Survey (ATUS). Five spousal variables are considered: the relative wage of the wife compared to her husband, spouse’s weekly hours of employment, and the spouse’s time in three unpaid activities. Each requires instrumentation in order to address issues of endogeneity and possible selection bias. In addition, in order to handle the problem that there is only a single time diary per household, two alternative strategies are explored: out-of-sample prediction and propensity matching. Using either method, the results show little effect of one spouse on the unpaid time use of parents. Most importantly, relative wage does not appear to affect time use choices of parents. There does appear to be a small consistent effect of one’s spouse’s leisure time on own leisure time; husband’s and wife’s leisure time appears to be complementary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This 50% figure reflects a steady decline in recent decades.

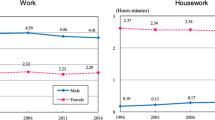

Devereux (2004) estimated the effect of changes in relative wages on husbands’ and wives’ labor supply. He found that men are largely unaffected by their wives’ labor supply but the wife’s own wage effect is positive and their response to increasing wages for their husbands is negative. Duguet and Simonnet (2007) find that in France, men’s labor force participation in 1997 is affected by their wives but not vice versa. Fisher et al. (2007) take the long view of men and women’s time use and find that there is a convergence of male and female patterns of time use over the period of the mid 1960’s to the early 2000s.

For examples of empirical evidence on gender differences in unpaid home production time both in the United States and internationally, see Hersch and Stratton (2002), Sousa-Poza et al. (2001), Bittman et al. (2003), and Alvarez and Miles (2003). Gupta and Stratton (2008) model the leisure time of individuals in a couple using relative education levels as their proxy for relative bargaining power

Our model is also similar to Hallberg and Klevmarken (2003) except home production and leisure time are modeled jointly with caregiving time.

Grossbard-Shechtman (2003) also includes the possibility of household production of a public good.

McElroy and Horney (1981) and Manser and Brown (1980) introduced the use of cooperative game theory to model the allocation of goods within a marriage using divorce as the threat point. The collective framework models of Chiappori (1988), Browning and Chiappori (1998), and Chiappori et al. (2002) also predict that income post divorce will affect negotiations of the share function. Only in the separate spheres model does income within an intact marriage matter to the game’s outcome.

Friedberg and Webb (2006, The chore wars: household bargaining and leisure time, unpublished) define relative wages as the wife’s wage as a share of the total household wage, wife’s wage plus husband’s wage. It is not clear why this would be preferable to the more straightforward wife’s wage/husband’s wage measure we use. Hersch and Stratton (1994) and Bittman et al. (2003) both use husband’s share of total labor income (husband’s income/ total couples’ income). Gupta and Stratton (2008) use own share of education (own education/ own education + spouse’s education).

This statement assumes that the marginal minute of unpaid household production time is a source of disutility.

There are several choices of wage values from the ATUS. We use hourly wages if hourly wages are provided. If hourly wage were not provided then we used weekly earnings divided by total hours usually worked per week. The estimation of the ln(wife’s wage/husband’s wage) uses a two-stage Heckman procedure in which the first stage estimates the probability that the wife is employed.

Stewart (2008) showed that non-employed men’s daily activities look similar to employed men’s activities on a non-work day, while for women, non-employed women’s daily activities are substantially different from the activities of employed women on non-work days.

Own weekly employment hours are also instrumented for the same reasons and estimated and identified in the same way. See Appendix B, Table 6 for full specification.

Alternatively, doing the task together may increase the process utility from the task. Sullivan (1996) finds that women enjoy home production tasks more when they are done simultaneously with their husbands.

We have not attempted to estimate the husband and wife time use equations together since we do not expect the correlation across husband’s and wife’s time use to be maintained through either of our methods to predict spousal time.

On the other hand, the ATUS provides spouses wage and employment hours, variables not available in the previous US time diaries and large sample sizes for both weekdays and weekends.

More than 200 articles indexed in Econlit use the term “propensity score” in their abstract in the 5 years from January 2004 to January 2009. Only 77 articles used the term “propensity score” in their abstract in the five previous years, Jan 1999 to Jan 2004. Dehejia and Wahba (2002) describe the propensity matching technique in great detail.

In other matching technique applications, matched variables are often the average of a given number of near matches. We have not employed this strategy because the averages of time uses from a number of “near husbands” loses the covariances among the three time uses of the same person and would thus be similar to the out of sample prediction strategy.

The only solution to the missing covariance problem is to have actual data on couples as in the British, German or Australian time use studies. A task for future research is to use these alternative time diary data sources to evaluate the importance of the unobserved covariances in couples’ time use compared to the effects of the observables.

See Kimmel and Connelly (2007) for a discussion of the generation of these child care price measures which rely on data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation.

See Kimmel and Connelly (2007) for more detail on the estimation of child care prices.

Sample sizes differ a bit depending on which model we are estimating.

We estimate the model with relative education proxying for relative wages and with predicted wage of the mother divided by predicted wage of the father. Both these alternatives yielded similar results to those presented here where the value is the log of predicted relative wage.

The propensity score is the dot product from the logit estimation beta vector and the actual values of each respondent’s X variables.

References

Alvarez, B., & Miles, D. (2003). Gender effect on housework allocation: Evidence from Spanish two-earner couples. Journal of Population Economics, 16, 227–242.

Bianchi, S., Wight, V., & Raley, S. (2005). Maternal employment and family caregiving: Rethinking time with children in the ATUS, paper presented at ATUS Early Results Conference, Bethesda MD, Dec. 2005.

Bittman, M., England, P., Sayer, L., Folbre, N., & Matherson, G. (2003). When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology, 109(1), 186–214.

Blau, F., & Kahn, L. (2007). Changes in the Labor Supply Behavior of Married Women: 1980–2000. Journal of Labor Economics, 25, 393–438.

Browning, M., & Chiappori, P. (1998). Efficient intra-household allocations: A general characterization and empirical tests. Econometrica, 66, 1241–1278.

Chiappori, P. (1988). Rational household labor supply. Econometrica, 56, 63–90.

Chiappori, P., Fortin, B., & Lacroix, G. (2002). Marriage market, divorce legislation and household labor supply. Journal of Political Economy, 110(1), 37–72.

Connelly, R. & Kimmel, J. (2007). The impact of nonstandard work on caregiving for young children, IZA Working Paper No. 3093, October.

Dehejia, R., & Wahba, S. (2002). Propensity Score-Matching Methods for Nonexperimental Causal Studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 151–161.

Devereux, P. (2004). Changes in Relative Wages and Family Labor Supply. Journal of Human Resources, 39(3), 696–722.

Duguet, E., & Simonnet, V. (2007). Labor market participation in France: An asymptotic least squares analysis of couples’ decisions. Review of Economics of the Household, 5(2), 159–179.

Fisher, K., Egerton, M., Gershuny, J., & Robinson, J. (2007). Gender convergence in the American heritage time use study. Social Indicators Research, 82(1), 1–33.

Fortin, B., & Lacroix, G. (1997). A test of the unitary and collective models of household labour supply. Economic Journal, 107, 933–955.

Gronau, R. (1977). Leisure, home production and work: The theory of the allocation of time revisited. The Journal of Political Economy, 85(6), 1099–1124.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (1984). A theory of allocation of time in markets for labour and marriage. Economic Journal, 94(376), 863–882.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (2003). A consumer theory with competitive markets for work in marriage. Journal of Socio-Economics, 31(6), 609–645.

Gupta, N., & Stratton, L. (2008). Institutions, social norms, and bargaining power: An analysis of individual leisure time in couple households, IZA Discussion Paper 3773, October.

Hallberg, D. (2003). Synchronous leisure, jointness, and household labor supply. Labour Economics, 10, 185–202.

Hallberg, D., & Klevmarken, A. (2003). Time for children: A study of parent’s time allocation. Journal of Population Economics, 16, 205–226.

Hamermesh, D. H. (2000). Timing, togetherness and time windfalls. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 601–623.

Hersch, J., & Stratton, L. (1994). Housework, wages and the division of housework time for employed spouses. American Economics Review, 84(2), 120–125.

Hersch, J., & Stratton, L. (2002). Housework and wages. The Journal of Human Resources, 37(1), 217–229.

Jenkins, S., & Osberg, L. (2005). Nobody to play with? The implicatons of leisure coordination. In D. Hamermesh & G. Pfann (Eds.), The economics of time use (pp. 113–145). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Kalenkoski, C., Ribar, D., & Stratton, L. (2005). “Parental child care in single parent, cohabiting, and married couple families: Time diary evidence from the United Kingdom,” American Economic Review, May.

Kalenkoski, C., Ribar, D., & Stratton, L. (2007). The effect of family structure on parents’ child care time in the United States and the United Kingdom. Review of Economics of the Household, 5(4), 353–384.

Kimmel, J., & Connelly, R. (2007). Mothers’ time choices in the United States: caregiving, leisure, home production and paid work. The Journal of Human Resources, 42(3), 643–681.

Kimmel, J., & Powell, L. (2006). Nonstandard work and child care choices of married mothers. Eastern Economic Journal, 32(3), 397–419.

Kooreman, P., & Kapteyn, A. (1987). A disaggregated analysis of the allocation of time within the household. Journal of Political Economy, 95(2), 223–249.

Lam, D. (1988). Marriage markets and assortative mating with household public goods. Journal of Human Resources, 23, 462–487.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. (1993). Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. Journal of Political Economy, 101(6), 988–1010.

Lundberg, S., Pollak, R., & Wales, T. (1997). Do husbands and wives pool resources: Evidence from the UK child benefit. Journal of Human Resources, 32(3), 463–480.

Maassen van den Brink, H., & Groot, W. (1997). A household production model of paid labor, household work and child care. De Economist, 145(3), 325–343.

Manser, M., & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and household decision making: A bargaining analysis. International Economic Review, 21, 31–44.

McElroy, M., & Horney, M. (1981). Nash-bargained decisions: Toward a generalization of the theory of demand. International Economic Review, 22(2), 333–349.

Pollak, R. (2005). Bargaining power in marriage: Earnings, wage rates and household production, NBER Working Papers: 11239.

Solberg, E., & Wong, D. C. (1992). Family time use: Leisure, home production, market work, and work related travel. The Journal of Human Resources, 27(3), 485–510.

Sousa-Poza, A., Schmid, H., & Widmer, R. (2001). The allocation and value of time assigned to housework and child-care: An analysis for Switzerland. Journal of Population Economics, 14, 599–618.

Stewart, J. (2008). The time use of nonworking men. In J. Kimmel (Ed.), How do we spend our time? Evidence from the American time use survey (pp. 123–148). Kalamazoo: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Sullivan, O. (1996). Time co-ordination, the domestic division of labour and affective relations: Time use and the enjoyment of activities within couples. Sociology, 30(1), 79–100.

Thomas, D. (1990). Intra-household resource allocation: An inferential approach. Journal of Human Resources, 25(4), 635–664.

Ward-Batts, (2008). Out of the wallet and into the purse: Using micro data to test income pooling. Journal of Human Resources, 43(2), 325–351.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Propensity matching

The matching process we used is a propensity matching strategy with replacement. The idea of any matching strategy is to replace the missing data with actual data from another respondent. The respondent who is missing data is matched on observable characteristics with a similar respondent who have the missing variable(s). Propensity score matching is a strategy that allows us to “match” on a large number of dimensions which increases the precision of the exercise. To create the propensity score, which serves the role of summarizing in a single number all the information we have on all the observables, the father and mother time diary sample are combined and we ran a logit to predict whether the data comes from the male or female sample. Following the procedure outlined in Dehejia and Wahba (2002), we began with a linear specification of age of both spouses, education of both spouses, race of both spouses, the usual employment hours of both spouses, the number of children and the presence of other adults in the household, the diary day and whether the diary was collected in the summer. We then added quadratic and cubic terms until the t-tests of the means of the 10 strata within the data showed no difference between the “matched” variables and the actual variables. In our case, there were a great number of variables the two data sets held in common, so the quality control tests were substantial.

The actual matching was done using the nearest neighbor criterion with sample replacement. The nearest neighbor criterion links each time diary respondent to the time diary respondent of the opposite sex with the closest propensity score.Footnote 28 We used a one-to-one match with replacement such that one husband record might be linked to more than one wife record if his propensity score is closer to each wife than any other potential husband’s score. Dehejia and Wahba (2002) explored the difference between matching with replacement or without and showed pros and cons of each approach.

Once the checking is completed, the variables supplied by the matched spouse were the three non-paid time levels, his or her predicted natural log of wage, and his or her predicted usual hours of weekly paid employment.

Appendix B

Appendix C

See Table 8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Connelly, R., Kimmel, J. Spousal influences on parents’ non-market time choices. Rev Econ Household 7, 361–394 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-009-9060-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-009-9060-y