Abstract

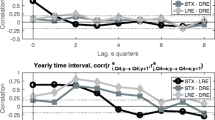

Motivated by investment-based asset pricing, we show that two firm fundamentals, investment and profitability, have substantial predictive power for REIT returns. The return predictability of investment and profitability is not subsumed by conventional models and can be useful for understanding the cross section of expected REIT returns. To illustrate, we construct an investment-based factor model for REITs that consists of a market factor, an investment factor, and a profitability factor. The investment-based model outperforms conventional models in capturing well-known cross-sectional patterns in REIT returns. Our findings suggest that incorporating investment-based asset pricing can be a promising direction for future real estate finance research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the context of REITs, a good example of investment is property acquisition, while profitability is determined by property income and price appreciation.

The construction of the REIT-based conventional factors is described in Appendix B.

Including cash holdings in total assets produces similar results. We exclude the cash holding component because it does not represent investments in productive assets. For example, Cooper et al. (2008) show that the cash holding component of asset growth does not carry much information about the future returns of common stocks.

We found similar results using the annual growth rate in net real estate investment or net property investment from SNL financial.

The REIT industry often promotes the use of (adjusted) funds from operation (FFO) as profitability measure. However, Vincent (1999) show that the GAAP net income provides (marginally) the most information about REIT performance among alternative measures of profitability. Using quarterly FFO data from SNL financial produces similar results.

Detailed definitions for the conventional characteristics are documented in Appendix A.

For brevity, our discussion focuses on results using the REIT-based conventional factors. Using the common stock-based conventional factors produces similar or stronger results in favor of our conclusions (results are available upon request).

Due to the limited sample size, we sort REITs into only three groups, instead of five, to make sure that the portfolios are reasonably diversified.

Hou et al. (2015a) construct a four-factor model that consists of a market factor, a size factor, an investment factor, and a profitability factor. To construct their factors, they form 18 portfolios using a two by three by three independent sort on size, investment, and profitability. Due to the limited sample size of REITs, we do not sort on size and thus do not include the size factor in our test.

The relatively low momentum factor premium from 1994 to 2013 is consistent with the finding of Feng et al. (2014) and can be partly attributed to the poor momentum return after the 2008 financial crisis.

Other conventional characteristics such as B/M have much weaker predictive power of REIT returns after 1990 (e.g., Chui, et al. 2003). Hence, we do not include them for brevity.

References

Ang, A., Hodrick, R. J., Xing, Y., & Zhang, X. (2006). The cross-section of volatility and expected returns. Journal of Finance, 61, 259–299.

Berk, J. B., Green, R. C., & Naik, V. (1999). Optimal investment, growth options, and security returns. Journal of Finance, 54, 1553–1607.

Bond, S. A., & Chang, Q. (2013). REITs and the private real estate market. In H. K. Baker & G. Filbeck (Eds.), Alternative investments – balancing opportunity and risk. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52, 57–82.

Chui, A. C. W., Titman, S., & John Wei, K. C. (2003a). The cross section of expected REIT returns. Real Estate Economics, 31, 451–479.

Chui, A. C. W., Titman, S., & John Wei, K. C. (2003b). Intra-industry momentum: the case of REITs. Journal of Financial Markets, 6, 363–387.

Cochrane, J. H. (1991). Production-based asset pricing and the link between stock returns and economic fluctuations. Journal of Finance, 46, 209–237.

Cochrane, J. H. (1996). A cross-sectional test of an investment-based asset pricing model. Journal of Political Economy, 104, 572–621.

Cochrane, J. H. (2011). Presidential address: discount rates. Journal of Finance, 66, 1047–1108.

Cooper, M. J., Gulen, H., & Schill, M. J. (2008). Asset growth and the cross-section of stock returns. Journal of Finance, 63, 1609–1651.

Davis, J. L., Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2000). Characteristics, covariances, and average returns: 1929 to 1997. Journal of Finance, 55, 389–406.

DeLisle, J. R., Price, M. K. S., & Sirmans, C. F. (2013). Pricing of volatility risk in REITs. Journal of Real Estate Research, 35, 223–248.

Derwall, J., Huij, J., Brounen, D., & Marquering, W. (2009). REIT momentum and the performance of real estate mutual funds. Financial Analysts Journal, 65, 24–34.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The cross-section of expected stock returns. Journal of Finance, 47, 427–465.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33, 3–56.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1996). Multifactor explanation of asset pricing anomalies. Journal of Finance, 51, 55–84.

Feng, Z., McKay Price, S., & Sirmans, C. F. (2014). The relationship between momentum and drift: industry-level evidence from equity real estate investment trusts (REITs). Journal of Real Estate Research, 36, 383–407.

Gao, X., & Ritter, J. R. (2010). The marketing of seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 97, 33–52.

Gibbons, M. R., Ross, S. A., & Shanken, J. (1989). A test of the efficiency of a given portfolio. Econometrica, 57, 1121–1152.

Glascock, J., & Lu-Andrews, R. (2014). “The Profitability Premium in Real Estate Investment Trusts”, Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2375431.

Goebel, P. R., Harrison, D. M., Mercer, J. M., & Whitby, R. J. (2013). REIT momentum and characteristic-related REIT returns. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 47, 564–581.

Hartzell, J., Muhlhofer, T., & Titman, S. (2010). Alternative benchmarks for evaluating mutual fund performance. Real Estate Economics, 38, 121–154.

Hou, K., Xue, C., & Lu, Z. (2015a). Digesting anomalies: an investment approach. Review of Financial Studies, 28, 650–705.

Hou, K., Xue, C., Lu, Z. (2015b). A comparison of new factor models, NBER Working Paper No. 20682.

Hung, S.-Y. K., & Glascock, J. (2008). Momentum profitability and market trend: evidence from REITs. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 37, 51–69.

Hung, S.-Y. K., & Glascock, J. (2010). Volatilities and momentum returns in real estate investment Trusts. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 41, 126–149.

Liu, L. X., Whited, T. M., & Lu, Z. (2009). Investment-based expected stock returns. Journal of Political Economy, 117, 1105–1139.

Price, M. K. S., Gatzlaff, D. H., & Sirmans, C. F. (2012). Information uncertainty and the post-earnings-announcement drift anomaly: insights from REITs. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 44, 250–274.

Vincent, L. (1999). The information content of funds from operations (FFO) for real estate investment trusts (REITs). Journal of Accounting and Economics, 26, 69–104.

Zhang, L. (2005a). The value premium. Journal of Finance, 60, 67–103.

Zhang, L. (2005b). Anomalies, NBER working paper 11322.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Real Estate Research Institute (RERI) in completing this research. We thank Qing Bai, David Geltner, Jung-Eun Kim, Doug Poutasse, Stuart Rosenthal, Jim Shilling, and Eva Steiner for helpful comments and participants at the RERI annual conference, the AREUEA national conference, the AREUEA International meeting, the RECAPNET annual conference, and the Asian Real Estate Society meeting. We also thank Calvin Schnure for assistance with the NAREIT equity REIT data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendices

A. Variable Definitions

Market Equity (ME), or size, is share price (item PRC) times the number of shares outstanding (item SHROUT) from CRSP.

Book-to-Market Equity (B/M) is book equity divided by market equity. Following Davis et al. (2000), we measure book equity as stockholders’ book equity, plus balance sheet deferred taxes and investment tax credit (item TXDITC) if available, minus the book value of preferred stock. Stockholders’ equity is the value reported by Compustat (item SEQ), if it is available. If not, we measure stockholders’ equity as the book value of common equity (item CEQ) plus the par value of preferred stock (item PSTK), or the book value of assets (item AT) minus total liabilities (item LT). Depending on availability, we use redemption (item PSTKRV), liquidating (item PSTKL), or par value (item PSTK) for the book value of preferred stock. Market equity is from Compustat (item PRCC_F times item CSHO) or CRSP at the fiscal year end. B/M is considered known four months after fiscal year end.

Momentum (MOM) for month t is measured as the cumulative stock return from month t-12 to month t-2 (skipping month t-1).

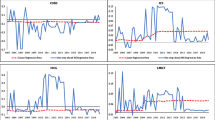

Investment (I/A) is measured as the annual growth rate in total non-cash assets (Compustat item AT minus item CHE). Annual investment rate is considered known four months after fiscal year end.

Profitability (ROE) is measured as quarterly return on equity (ROE), defined as income before extraordinary items (Compustat item IBQ) divided by one-quarter-lagged book equity. Book equity is shareholders’ equity, plus balance sheet deferred taxes and investment tax credit (item TXDITCQ) if available, minus the book value of preferred stock (item PSTKQ). Depending on availability, we use stockholders’ equity (item SEQQ), or common equity (item CEQQ) plus the book value of preferred stock, or total assets (item ATQ) minus total liabilities (item LTQ) in that order as shareholders’ equity. Quarterly ROE is deemed as known on the earnings announcement date (item RDQ).

Earnings Surprise (SUE) is measured as the standardized unexpected earnings (SUE). We calculate SUE as the change in the most recently announced quarterly earnings per share (Compustat item EPSPXQ) from its value announced four quarters ago divided by the standard deviation of this change in quarterly earnings over the prior eight quarters. We require a minimum of six quarterly observations of earnings change in calculating SUE. Earnings surprise is deemed as known on the earnings announcement date (item RDQ).

Idiosyncratic Volatility (IVOL): Following Ang et al. (2006), we measure a stock’s idiosyncratic volatility as the standard deviation of the residuals from regressing the stock’s returns on the Fama-French three factors. We require a minimum of 15 daily returns in calculating idiosyncratic volatility.

Share Turnover (TO) is the average daily share turnover during the past 6 months. Daily share turnover is the number of shares traded (CRSP item VOL) on a given day divided by the number of shares outstanding (item SHROUT) on the same day. Following Gao and Ritter (2010), we adjust the trading volume for REITs traded on NASDAQ before 2004. Specifically, we divide NASDAQ volume by 2 prior to February 2001, by 1.8 between February 2001 and December 2001, and by 1.6 between 2002 and 2003.

B. Construction of the REIT-Based Conventional Factors

The REIT-based market factor (r MKT ), is defined as the return on the FTSE NAREIT All Equity REIT Index minus the one-month Treasury bill rate. The construction of other conventional factors largely follows the standard Fama and French approach. At the beginning of each month, we sort all REITs into two portfolios based on their market equity. Independently, we sort REITs into three portfolio based on their B/M. The two-way sort on size and B/M produces six portfolios, which are value-weighted and rebalanced monthly. We define the size factor (r SMB ) as the return spread between the simple average of the three small-cap portfolios (small-growth, small-neutral, small-value) and the simple average of the three big-cap portfolios (big-growth, big-neutral, big-value). The B/M factor (r HML ) is defined as the return spread between the simple average of the small-value and big-value portfolios and the simple average of the small-growth and big-growth portfolios. Independently, we also sort REITs into three portfolios based on their return momentum. The two-way sort on size and momentum produces six portfolios, which are value-weighted and rebalanced monthly. The momentum factor (r UMD ) is the return spread between the simple average of the small-winner and big-winner portfolios and the simple average of the small-loser and big-loser portfolios. Summary statistics for the REIT-based conventional factors are presented in Table 9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bond, S., Xue, C. The Cross Section of Expected Real Estate Returns: Insights from Investment-Based Asset Pricing. J Real Estate Finan Econ 54, 403–428 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9573-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9573-0