Abstract

Foreclosure procedures in some states are considerably swifter and less costly for lenders than in others. In light of the foreclosure crisis, an empirical understanding of the effect of foreclosure procedures on the mortgage market is critical. This study finds that lender-favorable foreclosure procedures are associated with more lending activity in the subprime market. The study uses hand-coded state foreclosure law variables to construct a numerical index measuring the favorability of state foreclosure laws to lenders. Mortgage origination data from state-border areas shows that lender-friendly foreclosure is associated with an increase in subprime originations, but has less effect on the prime market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 1994, for example, subprime loans were less than 5 % of the mortgage market (Gramlich 2007).

The basic legal principles of foreclosure discussed herein are elaborated in Nelson and Whitman (2007).

Redemption rights are more common with respect to judicial foreclosure than nonjudicial foreclosure. In states that permit nonjudicial foreclosure, redemption rights attached to the rarely-used judicial foreclosure procedures are largely irrelevant.

States that explicitly permit contracting out of the right of redemption include Arkansas, Connecticut, and Tennessee. In Wisconsin the redemption period can be shortened to 6 months from 12 in the mortgage agreement.

California permits a two-year redemption period if a deficiency judgment is sought. New Jersey permits a six-month foreclosure period following a deficiency judgment. Since it is difficult for a bank to dispose of property that is subject to redemption, these rules create a substantial deterrence to seeking a deficiency judgment.

See “The Legal Dataset” and Table 1 for the relevant codings of state laws.

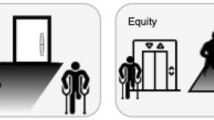

See also similar diagrams in Ho and Pennington-Cross (2007).

Rao et al. (2007) provides the most commonly used procedure in each state.

HMDA covers all federally insured depository institutions with assets in excess of $39 million.

Other studies have interpreted the 300 basis point threshold to indicate subprime originations (Bostic, et al. 2008).

2006 was the peak of subprime lending activity as measured by percentage of originations as a share of the total mortgage market (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University 2008).

HUD Subprime and Manufactured Home Lender List, available at http://www.huduser.org/portal/datasets/manu.html. Because 2005 was the last year that HUD compiled this list, matching 2006 HMDA data with the 2005 HMDA list might omit some subprime lenders that entered the market in 2006 and were not included on the 2005 list. These loans would be classified as prime, which would simply serve to attenuate the results presented below.

Since interest rates are not reported for rejected applications, identification strategies that rely on interest rates cannot identify subprime applications.

Actual foreclosure time for the District of Columbia is not computed in the Cutts and Merrill data. For these observations we impute a value by taking the average ratio between statutory foreclosure timeline and actual foreclosure timeline, and multiplying by the statutory foreclosure timeline for the District of Columbia. We also confirm that our results hold if the DC observations are simply dropped from the sample.

Measures of state and local tax rates are taken from the data collected by the Tax Foundation under “State and Local Tax Burdens,” available at http://www.taxfoundation.org/taxdata/show/335.html.

Unreported regressions include an interaction term for foreclosure law and predatory lending law, but the interaction term is not significant.

References

Bauer, P. B. (1985). Judicial foreclosure and statutory redemption: the soundness of Iowa’s traditional preference for protection over credit. Iowa Law Review, 71, 1.

Bostic, R. W., Engel, K. C., McCoy, P. A., Pennington-Cross, A., & Wachter, S. M. (2008). State and local anti-predatory lending laws: the effect of legal enforcement mechanisms. Journal of Economics and Business, 60(1–2), 47–66.

Bridewell, D. A. (1938). Effects of defective mortgage laws on home financing. The Law and Contemporary Problems, 5, 545.

Calem, P. S., Gillen, K., & Wachter, S. (2004). The neighborhood distribution of subprime mortgage lending. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 29(4), 393–410.

Capozza, D., & Thomson, T. (2006). Subprime transitions: lingering or malingering in default? Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 33(3), 241–258.

Clauretie, T. M., & Herzog, T. (1990). The effect of state foreclosure laws on loan losses: evidence from the mortgage insurance industry. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 22(2), 221–233.

Clauretie, T. M. (1989). State foreclosure laws, risk shifting, and the PMI industry. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 56(3), 544–554.

Cutts, A., & Merrill, W. (2008). Interventions in mortgage default: Policies and practices to prevent home loss and lower costs. In N. Retsinas & E. Belsky (Eds.), Borrowing to live: Consumer credit and mortgages revisited. Brookings Institution Press.

Fairchild, W. (1937). Foreclosure methods and costs: a revaluation. Brooklyn Law Review, 7, 1.

Ghent, A. C., & Kudlyak, M. (2011). Recourse and residential mortgage default: evidence from US states. Review of Financial Studies, 24(9), 3139–3186.

Gramlich, E. M. (2007). Subprime mortgages: America’s latest boom and bust. Urban Institute Press.

Ho, G., & Pennington-Cross, A. (2007). The varying effects of predatory lending laws on high-cost mortgage applications. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 89(1), 39–59.

Meador, M. (1982). The effect of mortgage laws on home mortgage rates. Journal of Economics and Business, 34(2), 143–148.

Mian, A., Sufi, A., & Trebbi, F. (2011). Foreclosures, house prices, and the real economy. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 16685.

Negroni, A. L. (2000). Residential mortgage lending: State regulation manual. Callaghan & Co.

Nelson, G. S., & Whitman, D. A. (2007). Real estate finance law (5th ed.). West.

Pence, K. M. (2006). Foreclosing on opportunity: state laws and mortgage credit. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(1), 177–182.

Pennington-Cross, A., & Ho, G. (2008). Predatory lending laws and the cost of credit. Real Estate Economics, 36(2), 175–211.

Pennington-Cross. (2010). The duration of foreclosures in the subprime mortgage market: a competing risks model with mixing. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 40(2), 109–129.

Qi, M., & Xiaolong, Y. (2009). Loss given default of high loan-to-value residential mortgages. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(5), 788–799.

Rao, J., Williamson, O., & Twomey, T. (2007). Foreclosures: Defenses, workouts, and mortgage servicing (2nd ed.). National Consumer Law Center.

Schill, M. H. (1991). Economic analysis of mortgagor protection laws. Virginia Law Review, 77, 489.

Wechsler, S. (1984). Through the looking glass: foreclosure by sale as De Facto Strict Foreclosure-An empirical study of mortgage foreclosure and subsequent resale. Cornell Law Review, 70, 850.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curtis, Q. State Foreclosure Laws and Mortgage Origination in the Subprime. J Real Estate Finan Econ 49, 303–328 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-013-9437-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-013-9437-9