Abstract

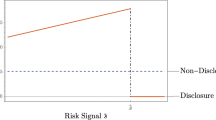

Advances in technology, as well as regulatory and legislative actions, have led to an increase in the quantity of information available to the public. This paper experimentally examines the effects of information quantity and consistency (or directional agreement) on the judgments and trading behavior of naïve investors, holding constant the quality (or predictive value) of information. In my experiment, investors receive accounting signals and make predictions and trading decisions for 24 separate firms. I find that increasing the quantity and consistency of information leads naïve investors to show greater judgment confidence and trading aggressiveness. Increased quantity reduces investors’ expected wealth in laboratory markets, while the effect of consistency on expected wealth depends on the relationship between the low- and high-quality signals investors receive. Results highlight possible unintended consequences of increased disclosure and suggest directions for future experimental and archival research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some prior research has examined trading activity in response to differences in the strength and weight of information (Nelson et al. 2001; see Griffin and Tversky 1992). While information consistency may be considered similar to information strength (i.e., the extremeness of the available information in support of a particular hypothesis), information quantity should not be considered as similar to information weight (i.e., the credence of the information) precisely because information quantity and quality need not necessarily be highly correlated. Thus, an increase in the quantity of information does not necessarily indicate an increase in its weight.

For example, Štraser (2002) reports an increase in information asymmetry between more- and less-informed informed investors since Reg FD, consistent with the quality of public information not increasing with quantity. Other studies provide evidence of increased information gathering effort by analysts and increased forecast dispersion, suggesting a reduction in the quality of information flowing to analysts (Agrawal and Chadha 2003; Bailey et al. 2003; Irani and Karamanou 2003; Mohanram and Sunder 2003; O’Sullivan 2006). However, Heflin et al. (2003) do not find evidence consistent with impairment of the information environment, and some of their results reflect improvement.

Interestingly, Peterson and Pitz (1988) do not find a significant effect of consistency on confidence (see their experiment 4) and attribute the lack of effect to consistency not being a salient feature of their experimental setting. In contrast, consistency is likely to be a salient feature of naïve investors’ information in trading contexts, so my experimental setting provides a more powerful test of its effect on judgment confidence.

Signals were given using accounting terms with which all participants were familiar. Naïve investors may therefore have been able to draw inferences about signal quality. However, any ability to do this accurately biases against finding treatment effects of signal quantity or consistency.

Some features of my experimental setting are similar to those used in Bloomfield et al. (1999). Specifically, Bloomfield et al. (1999) generate signals from public data sets, and give them to some traders without information about their statistical properties, while other traders also get that information. (they call such information “guidance”). This paper examines how naïve investors respond to changes in the quantity and consistency of their signals in a similar trading environment.

Because the reservation price is equivalent to a probability estimate, this measure is consistent with the psychology literature on confidence (see Lichtenstein et al. 1982).

Balancing the consistency of the firms in this way ensures that the correlations between each signal and the ROE variable for the 24 specific firms used in the experiment are relatively unchanged from those in the dataset from which the securities are drawn.

For example, if a firm’s change in gross margin ratio was greater than 40% of that of all other firms in a given year, the value for that measure was 40 for that firm-year.

Because these variables are used to predict a binary dependent measure, a purely nondiagnostic signal will predict correctly about 50% of the time on average, by chance. Thus, the closer a variable’s correct prediction percentage is to 50%, the less diagnostic that variable is.

Whether naïve investors received the high- or low-quantity set of firms first was balanced. However, in order to discuss verbally the differences between naïve and informed investors, it was necessary to separate the naïve investors who received the low-quantity group first from those who received the high-quantity group first. Therefore, sessions with each group of naïve investors were conducted separately. Investors were randomly assigned to treatment conditions.

Investors were constrained to select a reservation price in the range [$0, $0.50] if they had predicted below-median ROE and in the range [$0.50, $1] if they had predicted above-median ROE. This was explained as reflecting the reservation price as an expression of the probability that future ROE would be above median ROE (i.e., if they predicted below-median ROE, they must believe that probability to be below 0.50, and vice versa).

Investors did not receive immediate feedback about the results of their trades; thus opportunities for learning were precluded. Section 5 contains a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of this approach.

p-values for simple effects tests are one-tailed. All other reported p-values are two-tailed.

The expected value represents investors’ optimal reservation price. Each firm’s expected value is calculated from a regression equation obtained from the dataset from which the experimental securities were drawn. The regression equation includes an intercept and the beta coefficient associated with the high-quality signal (with low-quality signals omitted because they are, by design, nondiagnostic).

This measure allows the clearinghouse market to capture two effects of trading aggressiveness on wealth. Specifically, because market prices are determined by reservation prices and share numbers, naïve investors who are more aggressive not only trade more shares at a loss but trade at a greater loss per share. I thank the referee for recommending this measure.

Tests based on actual market prices are less informative for two primary reasons. First, investors did not always trade optimally, creating noise that is unrelated to the effects of interest. Second, because the number of naïve investors was twice that of informed investors, there was a large number of transactions in which naïve investors were on both sides of the trade, which would dampen aggregate wealth effects. Results based on actual market prices are therefore slightly weaker, though inferentially similar. Specifically, the quantity effect does not reach statistical significance.

References

Agrawal, A., & Chadha, S. (2003). Who is afraid of Reg FD? The behavior and performance of sell-side analysts following the SEC’s fair disclosure rules. Journal of Business, 79, 2811–2834.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2002). How the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 impacts the accounting profession. http://www.aicpa.org/info/Sarbanes-Oxley2002.asp.

Arkes, H., Dawes, R., & Christensen, C. (1986). Factors influencing the use of a decision rule in a probabilistic task. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37, 93–110.

Bailey, W., Li, H., Mao, C., & Zhong, R. (2003). Regulation fair disclosure and earnings information: Market, analyst, and corporate responses. Journal of Finance, 58, 2489–2516.

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2000). Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. Journal of Finance, 55, 773–806.

Bassett, R., & Storrie, M. (2003). Accounting at energy firms after Enron: Is the cure worse than the disease? Cato Institute Project on Corporate Governance, Audit, and Tax Reform. Policy Analysis, 469, 1–17.

Beattie, V., Dhanani, A., & Jones, M. J. (2008). Investigating presentational change in UK annual reports. Journal of Business Communication, 45(18), 1–222.

Bloomfield, R., Libby, R., & Nelson, M. (1996). Communication of confidence as a determinant of group judgment accuracy. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68, 287–300.

Bloomfield, R., Libby, R., & Nelson, M. (1999). Confidence and the welfare of less-informed investors. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24, 623–647.

Bloomfield, R., Libby, R., & Nelson, M. (2000). Underreactions, overreactions and moderated confidence. Journal of Financial Markets, 3, 113–137.

Bloomfield, R., Libby, R., & Nelson, M. (2003). Do investors overrely on old elements of the earnings time series? Contemporary Accounting Research, 20, 1–31.

Bonner, S. E., Walther, B., & Young, S. (2003). Sophistication-related differences in investors’ models of the relative accuracy of analysts’ forecast revisions. The Accounting Review, 78, 679–706.

Bukszar, E. (2003). Does overconfidence lead to poor decisions? A comparison of decision making and judgment under uncertainty. Journal of Business and Management, 9, 33–43.

Byrnes, N. (2002). The downside of disclosure: Too much data can be a bad thing. Business Week, 3796, 100.

Camerer, C. F., & Lovallo, D. (1999). Overconfidence and excess entry: An experimental approach. American Economic Review, 89, 306–318.

Camerer, C., & Weber, M. (1992). Recent developments in modeling preferences: Uncertainty and ambiguity. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 325–370.

D’Avolio, G., Gildor, E., & Shleifer, A. (2001). Technology, information production, and market efficiency. In Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Policy for the Information Economy, 125–160.

Elliott, W. B., Hodge, F., & Jackson, K. E. (2008). The association between nonprofessional investors’ information choices and their portfolio returns: The importance of investing experience. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25, 473–498.

Gill, M. J., Swann, W. B., Jr, & Silvera, D. H. (1998). On the genesis of confidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1101–1114.

Goodwin Procter. (2003). SEC approves final NYSE and Nasdaq corporate governance standards. Public Company Advisory. http://goodwinprocter.com/~/media/CD2362B212BC458AB017D855BF747833.ashx. Cited 11 Nov 2003.

Griffin, D., & Tversky, A. (1992). The weighting of evidence and the determinants of confidence. Cognitive Psychology, 24, 411–435.

Hall, C. C., Ariss, L., & Todorov, A. (2007). The illusion of knowledge: When more information reduces accuracy and increases confidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103, 277–290.

Heflin, F., Subramanyam, K., & Zhang, Y. (2003). Regulation FD and the financial information environment: Early evidence. The Accounting Review, 78, 1–37.

Iglesias, C. (2003). Mondo quarterlies. http://www.irmag.com/static/disclosure/USCanada/MondoQuarterlies0203.htm.

Irani, A., & Karamanou, I. (2003). Regulation fair disclosure, analyst following, and analyst forecast dispersion. Accounting Horizons, 17, 15–29.

Lichtenstein, S., Fischoff, B., & Phillips, L. (1982). Calibration of probabilities: The state of the art to 1980. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (pp. 306–334). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Maines, L. A., Salamon, G. L., & Sprinkle, G. B. (2006). An information economic perspective on experimental research in accounting. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 18, 85–102.

Mohanram, P., & Sunder, S. (2003). How has Regulation FD affected the operations of financial analysts? Contemporary Accounting Research, 23, 491–525.

Nelson, M. W., Bloomfield, R. J., Hales, J. W., & Libby, R. (2001). The effect of information strength and weight on behavior in financial markets. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 168–196.

Nelson, M. W., Krische, S. D., & Bloomfield, R. J. (2003). Confidence and investors’ reliance on disciplined trading strategies. Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 503–523.

O’Sullivan, K. (2006). Hungry for more. CFO, 22, 54–60.

Oskamp, S. (1965). Overconfidence in case-study judgments. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29, 261–265.

Ou, J., & Penman, S. (1989). Financial statement analysis and the prediction of stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 11, 295–329.

Paese, P. W., & Sniezek, J. A. (1991). Influences on the appropriateness of confidence in judgment: Practice, effort, information, and decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 48, 100–130.

Paredes, T. (2003). Blinded by the light: Information overload and its consequences for securities regulation. Washington University Law Quarterly, 2, 417–485.

Peterson, D., & Pitz, G. (1988). Confidence, uncertainty, and the use of information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14, 85–92.

Potter, G. (1992). Accounting earnings announcements, institutional investor concentration, and common stock returns. Journal of Accounting Research, 30, 146–155.

Ronis, D. L., & Yates, J. F. (1987). Components of probability judgment accuracy: Individual consistency and effects of subject matter and assessment method. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 40, 193–218.

Ryback, D. (1967). Confidence and accuracy as a function of experience in judgment making in the absence of systematic feedback. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 25, 331–334.

Salthouse, T. A. (1991). Expertise as the circumvention of human processing limitations. In K. A. Ericsson & J. Smith (Eds.), Toward a general theory of expertise: Prospects and limits (pp. 286–300). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The paradox of choice: Why more is less. New York: Harper Perennial.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2000). Final rule: Selective disclosure and insider trading. http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-7881.htm.

Securities Industry Association. (2001). Costs and Benefits of Regulation Fair Disclosure, mimeo.

Štraser, V. (2002). Regulation Fair Disclosure and information asymmetry. Working paper, University of Notre Dame. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=311303.

Tweedie, D., & Whittington, G. (1990). Financial reporting: Current problems and their implications for systematic reform. Accounting and Business Research, 21, 87–102.

Unger, L. (2001). Testimony concerning Regulation Fair Disclosure. http://www.sec.gov/news/testimony/051701tslu.htm. Cited 17 May 2001.

VanGetson, A. J. (2003). Real-time disclosure of securities information via the internet: Real-time or not right now? University of Illinois Journal of Law, Technology& Policy, 2, 551–571.

Yunker, J., & Krehbiel, T. (1988). Investment analysis by the individual investor. Quarterly Review of Economics and Business, 28, 90–101.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on my dissertation, completed at Cornell University. I thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mark Nelson (chair), Rob Bloomfield, David Dunning, and Martin Wells. This paper has also benefited from the comments and assistance of Rachel Birkey, Jake Birnberg, Ethan Burris, Shana Clor-Proell, Kristen Ebert-Wagner, Brooke Elliott, Harry Evans, Jeffrey Hales, Vicky Hoffman, Kevin Jackson, Susan Krische, Ben Landfried, Bob Libby, Don Moser, Derek Oler, Marc Picconi, Bill Tayler, Jeff Wilks, and workshop participants at Cornell, Georgia State, and the universities of Illinois, Pittsburgh, and Utah. I also gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance of the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University and the Deloitte Foundation Doctoral Fellowship Program, as well as access to experimental participants provided by Cornell University, Brigham Young University, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, S.D. Confidence and trading aggressiveness of naïve investors: effects of information quantity and consistency. Rev Account Stud 15, 295–316 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9106-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9106-7