Abstract

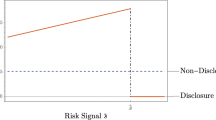

This paper explores the idea of disclosure clienteles. Disclosure clienteles refer to the ability of different types of disclosure activities to differentially benefit investors with varying levels of sophistication. Disclosure clienteles exist because variation in investor sophistication affects investors’ ability to utilize disclosed information and thus their preferences for distinct disclosure activities. I use cross-sectional variation in inefficient exercise activity in the options market to identify variation in sophistication (e.g., investors’ attention, knowledge, and expertise) and then present empirical evidence consistent with disclosure clienteles. The results show that sophisticated investors concentrate their trading in firms that regularly issue earnings guidance. This relation is stronger before RegFD, when sophisticated investors’ preferences for forecasting firms are predicted to be greater. Alternatively, less sophisticated investors are more prevalent in firms with increased levels of press-dissemination and superior investor relations (e.g., better access to information on the corporate website). These results suggest investors’ demand for disclosure is partially driven by their ability to use disclosed information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout the paper, I use the terms “sophisticated investors” and “sophisticated information processors” interchangeably.

Further anecdotal evidence provided by an interview with an academic consultant for derivative markets suggests the presence of unsophisticated (retail) investors in the options market has increased due to the increase in online option brokerage activity.

Understanding when early exercise is optional also requires some level of sophistication. I discuss the sophistication measure in more detail in Sect. 3.1 and in an internet appendix.

Institutional investors face additional considerations that affect their trading (e.g., fiduciary responsibilities and liquidity needs), which are unrelated to their level of sophistication (Bushee and Noe 2000; Bushee 2004; Bushee and Goodman 2007). Furthermore, institutional investors vary in their level of sophistication, and prior research has shown that retail investors vary in their level of sophistication as well (Grinblatt and Keloharju 2000; Coval 2005; Grinblatt et al. 2011).

Consequently, I find similar disclosure-related results (untabulated) if I control for the different types of institutional ownership, as opposed to the overall level of institutional ownership in the firm.

Indjejikian (1991) also models a setting in which investors vary in their level of sophistication and hence in their ability to extract information from firm disclosures.

Bloomfield (2002) argues that less sophisticated investors are likely to overlook data that is harder to interpret and require more resources (e.g., time and attention) to assimilate, due to the cognitive difficulty of extracting information from such data. Hirshleifer and Teoh (2003) argue that if time and attention is costly to allocate, investors will be inattentive to certain disclosures.

Press dissemination differs from the number of press releases provided by the firm. Press dissemination relates to the relative distribution of a firm-initiated press release (news). While dissemination may be related to the number of press articles a firm releases, it is meant to capture the construct of (increased) accessibility of information.

Hong and Huang (2005) describe a similar benefit, which arises from the manager’s desire to increase the liquidity of the firm’s block shares.

Furthermore, forecasts can be issued for a variety of additional reasons including (1) aligning the market’s expectation with that of the manager (Ajinkya and Gift 1984; King et al. 1990), (2) informing analysts (Hutton 2005; Cotter et al. 2006), (3) reducing expected litigation costs by providing forthcoming disclosure about negative performance (Skinner 1994), and (4) affecting insider trading profits (Rogers and Stocken 2005; Rogers 2008).

In related work, Botosan and Plumlee (2002) find that the cost of capital increases with more timely disclosures.

Anantharaman and Zhang (2011) find that firms increase guidance in response to declines in analyst coverage, in an effort to regain coverage. This also implies that forecasts are meant for sophisticated users (intermediaries).

Options in which early exercise is optimal are characterized by the fact that they are deep in the money and have a relatively short remaining horizon. For example, the median (mean) option in the sample is approximately $8 ($12) in the money and has 16 (30) calendar days to maturity on the last cum date. Therefore most of these options will need to be exercised soon in any case, and the incremental cost associated with early exercise is likely to be insignificant. Furthermore, sophisticated investors face limited transaction costs. Within the retail sector, more sophisticated customers who work with full-service brokers on a fee basis do not pay commissions per transaction and would have no additional costs associated with this decision. Hence, even in the face of any transaction costs, sophisticated investors are more likely to gain from early exercise due to the lower costs they face and are more likely to exercise their options efficiently.

In untabulated robustness tests, I find similar results using alternative aggregation techniques.

Soltes’s sample is available for a subset of firms for the period 2001–2006, due to the industry and size restrictions he imposes, as well as the need to identify Factiva codes and contact identifiers. I am extremely grateful to Eugene Soltes for providing me with the relevant data to test this relation.

I am extremely grateful to Karl Lins for providing me access to this data set.

In 2002, IR Magazine ranked more than 200 firms.

As an additional robustness test, I also examine the relation between the sophistication measure and IR only for firms rated by IR Magazine (see Sect. 4.3). I find similar results using this approach. In untabulated results, I define the top 10 (20) variable using the raw (unadjusted) scores reported by IR Magazine. I reach similar inferences using this alternative definition, and the resulting coefficients and t-stats resemble those reported in Table 4.

Among firms categorized as having superior IR activities and among those that provide ongoing forecasts, approximately 85 % of the observations are defined as such throughout the sample. The level of press dissemination in the firm is also relatively persistent throughout my sample. The coefficient from a simple AR(1) model within the sample is approximately 0.85.

I define an industry using the Fama–French 12 industry definition. I do not use the Fama–French 49 industry definition in my primary analysis because I have a limited number of observations in many of the industries defined using this approach. The Fama–French 12 industry definition is also more likely to be associated with the “type” of industry categories investors consider when choosing in which assets to invest.

Agarwal et al. (2011) provide one potential explanation for the lower levels of hedge fund ownership observed in quintile 1. They document that hedge funds file for short term “confidential holdings” when trading on proprietary information, which are not captured by 13-f filings. They show that this activity is more prevalent in firms with higher levels of information asymmetry where the measure is hypothesized to be lower. Therefore the measured level of hedge fund ownership is predicted to be lower in firms with higher levels of information asymmetry, where the measure is hypothesized to be lower.

I find similar differences using a small sample approach. Specifically, I compute the level of hedge fund ownership in the firm’s equity for a random sample of firms in the top and bottom decile of the sophistication measure in 2007, using detailed information from Thomson ONE Banker. The mean level is 7.8 % relative to 1.6 % for firms in the bottom versus top decile, while the median level is 4.5 % relative to 1.2 % for the same firms. These differences are significant at the 5 % level. This result is also robust to alternative definitions of hedge fund ownership used by Thomson ONE Banker.

In untabulated analyses I find the concentration of sophisticated investors is larger in firms with higher levels of information asymmetry, as measured by higher levels of PIN, lower market capitalization, and higher return volatility and market-to-book ratios. Additionally, I find a higher concentration of less sophisticated investors in firms with increased liquidity in firm shares, as measured by higher share turnover and inclusion in the Dow Jones Industrial Index. These results are consistent with the predictions of Admati and Pfleiderer (1988) and Bhushan (1991) and provide further construct validity for the sophistication measure.

The correlation between ROA and MTB (assets) in my sample is 0.75 (untabulated). Therefore, to avoid multicollinearity issues, I exclude ROA as an additional control variable in the regressions. However, in untabulated robustness tests, I find that the inclusion of ROA does not materially change the results.

In this analysis, I define an IR z-score based on the average score and standard deviation in a given year. The IR z-score is used to make the scores comparable across years. I substitute the IR z-score for the IR Rank variable in the regressions in Table 4, Column (3). The relation between the sophistication measure and the IR z-score remains positive and statistically significant (t-stat of 1.84) despite the significant decline in sample size.

As a robustness test, I re-define forecasting firm as ln(1 + the number of forecasts issued over the prior year). The coefficients for this variable are also negative and significant with similar magnitudes.

My assumption is that the First Call Database includes forecasts issued before RegFD that were not made public using traditional newswire dissemination channels. Chuk et al. (2012, pp. 5 and 32) provide evidence that supports this assumption. Their evidence is consistent with First Call accessing alternative information sources and including forecasts (in their Database) that are not associated with a press release before RegFD.

For comparison, Chuk et al. (2012) define high analyst coverage as greater than five analysts covering the firm.

Nevertheless, because Chuk et al. (2012) highlight that the bias in coverage is significantly larger in earlier periods (e.g., before 1998), the results are re-examined post 1997 and from 2001 onward. These results (untabulated) resemble the ones presented in Table 7. The coefficient for forecasting firms remains negative (−1.5 % post 1997 and −1.2 % from 2001 onward) and statistically significant (t-stats of 2.35 and 1.91 respectively).

Of these cases, most firms initiate a forecasting policy only once throughout the sample (71 %), and 94 % of the firms initiate a forecasting policy no more than twice throughout the sample. These results suggest that the identification strategy used to detect forecast initiation is reasonable.

As a robustness test, I examine cases when the firm issued at least four forecasts during the year before the last cum date and no forecasts during the year before the lagged observation (lagged last cum date). I find 49 distinct cases using this approach. The coefficients for forecast initiation are much larger using this approach. The average coefficient is −0.15 with t-stats ranging from 2.6 to 4.0.

As a robustness test, I also identify “guidance stoppers” as firms that issue at least one forecast in three of the four quarters before the lagged observation (lagged last cum date) and zero forecasts in the year before the last cum date. I find only 21 instances using this approach. The coefficients in these regressions are also positive and significant. However, the coefficients are much larger ranging from 0.19 to 0.21.

For the IR Rank analysis I focus on the Top 10 score.

Furthermore, one can take partial comfort if the likelihood of issuing guidance (being a top rated IR firm) is similar across the groups, based on a relatively comprehensive set of control variables, suggesting that it is somewhat less likely that there is a material omitted variable.

As there are a much smaller number of observations ranked in the top 10 (20), I use multiple neighbor matching to create a matched sample for the IR analysis. Specifically, I match each top 10 (20) observation to up to three nontop observations with the smallest difference in propensity scores. Again, I require the difference for each observation to be below 0.10 (and thus not all observations receive three matches).

References

Admati, A. R., & Pfleiderer, P. (1988). A theory of intraday patterns: Volume and price variability. Review of Financial Studies, 1, 3–40.

Agarwal, V., Bellotti, X. A. & Taffler, R. J. (2010). The value relevance of effective investor relations. Financial Management.

Ajinkya, B. B., & Gift, M. J. (1984). Corporate manager’s earnings forecasts and symmetrical adjustments of market expectations. Journal of Accounting Research, 22, 425–444.

Amiram, D., Owens, E. & Rosenbaum O. (2012). Do public disclosures increase or decrease information asymmetry? New evidence from analyst forecast announcements. Columbia Business School working paper.

Anantharaman, D., & Zhang, Y. (2011). Cover me: Managers’ responses to changes in analyst coverage in the post-regulation FD reriod. The Accounting Review, 86, 1851–1885.

Ang, A., Turan, B. G., & Cakici, N. (2014). The joint cross section of stocks and options. Journal of Finance, 69, 2279–2337.

Anilowski, C., Feng, M., & Skinner, D. J. (2007). Does earnings guidance affect market returns? The nature and information content of aggregate earnings guidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44, 36–63.

Baker, M., Coval, J., & Stein, J. C. (2007). Corporate financing decisions when investors take the path of least resistance. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 266–298.

Beyer, A., Cohen, D. A., Lys, T. Z., & Walther, B. R. (2010). The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 296–343.

Bhushan, R. (1991). Trading costs, liquidity and asset holdings. Review of Financial Studies, 4, 343–360.

Bloomfield, R. J. (2002). The incomplete revelation hypothesis and financial reporting. Accounting Horizons, 16, 233–243.

Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2002). A re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 21–40.

Brennan, M. J., & Tamarowski, C. (2000). Investor relations, liquidity and stock prices. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 12, 26–37.

Bushee, B. J. (1998). The influence of institutional investors on myopic R&D investment behavior. The Accounting Review, 18, 207–246.

Bushee, B. J. (2001). Do institutional investors prefer near-term earnings over long-run value? Contemporary Accounting Research, 18, 207–246.

Bushee, B. J. (2004). Attracting the “right” investors; evidence on the behavior of institutional investors. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 16, 28–36.

Bushee, B. J., Core, J. E., Guay, W. R., & Hamm, S. J. W. (2010). The role of the business press as an information intermediary. Journal of Accounting Research, 48, 1–19.

Bushee, B. J., & Goodman, T. H. (2007). Which institutional investors trade based on private information about earnings and returns. Journal of Accounting Research, 45, 289–321.

Bushee, B. J., Matsumoto, D. A., & Miller, G. S. (2003). Open versus closed conference calls: The determinates and effects of broadening access to disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 34, 149–180.

Bushee, B. J., & Miller, G. S. (2012). Investor relations, firm visibility and investor following. The Accounting Review, 87, 867–897.

Bushee, B. J., & Noe, C. F. (2000). Corporate disclosure practices, institutional investors, and stock return volatility. Journal of Accounting Research, 38, 171–202.

Bushman, R. M., Gigler, F., & Indjejikian, R. J. (1996). A model of two-tiered financial reporting. Journal of Accounting Research, 34, 51–73.

Byrd, J., Goulet, W., & Johnson, M. (1993). Finance theory and the new investor relations. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 6(2), 48–54.

Chen, S., Matsumoto, D., & Rajgopal, S. (2011). Is silence golden? An empirical analysis of firms that stop giving quarterly earnings guidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 51, 134–150.

Cheong, F. S., & Thomas, J. (2011). Why do EPS forecast error and dispersion not vary with scale? Implications for analyst and managerial behavior. Journal of Accounting Research, 49(2), 359–413.

Chuk, E., Matsumoto, D. A., & Miller, G. S. (2012). Assessing methods of identifying management forecasts: CIG vs. researcher collected. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 54, 23–42.

Coller, M., & Yohn, T. L. (1997). Management forecasts and information asymmetry: An examination of bid-ask spreads. Journal of Accounting Research, 35–2, 181–191.

Cotter, J., Tuna, I., & Wysocki, P. D. (2006). Expectations management and beatable targets: How do analysts react to explicit earnings guidance? Contemporary Accounting Research, 23, 593–628.

Coval, J. D., Hirshleifer, D. A. & Shumway, T. (2005). Can individual investors beat the market? Harvard Business School finance working paper, No. 4-25.

Deller, D., Stubenrath, M., & Weber, C. (1999). A survey on the use of the internet for investor relations in the U.S.A., the U.K., and Germany. European Accounting Review, 8, 351–364.

Dyke, A., Volchkova, N., & Zingales, L. (2008). The corporate governance role of the media: Evidence from Russia. Journal of Finance, 63, 1093–1135.

Dyke, A., Zingales, & L. (2002). The bubble and the media. Corporate Governance and Capital Flows in a Global Economy, pp. 83–104.

Engelberg, J. E., & Parsons, C. A. (2011). The causal impact of media in financial markets. Journal of Finance, 66, 67–97.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43, 153–193.

Fischer, P., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1999). Public information and heuristic trade. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 27, 89–124.

Francis, J., Nanda, D., & Olsson, P. (2008). Voluntary disclosure, earnings quality, and cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 53–99.

Francis, J., Nanda, D., & Wang, X. (2006). Re-examining the effects of regulation fair disclosure using foreign listed firms to control for concurrent shocks. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 41, 271–292.

Frank, K. A. (2000). Impact of a confounding variable on a regression coefficient. Sociological Methods and Research, 29, 147–194.

Gintschel, A., & Markov, S. (2004). The effectiveness of regulation FD. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 37, 293–314.

Gould, J. F., & Kleidon, A. W. (1994). Market maker activity on Nasdaq: Implications for trading volume. Stanford Journal of Law, Business and Finance, 1, 1–17.

Gow, I., Ormazabal, G., & Taylor, D. (2010). Correcting for cross-sectional and time-series dependence in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 85, 483–512.

Grinblatt, M., & Keloharju, M. (2000). The investment behavior and performance of various investor types: A study of Finland’s unique data set. Journal of Financial Economics, 55, 43–67.

Grinblatt, M., Keloharju, M., & Linnainmaa, J. (2011). IQ, trading behavior, and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(2), 339–362.

Hao, J., Kalay, A., & Mayhew, S. (2009). Ex-dividend arbitrage in option markets. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 271–303.

Hirshleifer, D., & Teoh, S. H. (2003). Limited attention, information disclosure and financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36, 337–386.

Hong, H., & Huang, M. (2005). Talking up liquidity: Insider trading and investor relations. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 14, 1–31.

Houston, J. F., Lev, B., & Tucker, J. W. (2010). To guide or not to guide? Causes and consequences of stopping quarterly guidance. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27, 143–185.

Hutton, A. P. (2005). Determinants of managerial earnings guidance prior to Regulation Fair Disclosure and bias in analysts’ earnings forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research, 22, 867–914.

Indjejikian, R. (1991). The impact of costly information interpretation on firm disclosure decisions. Journal of Accounting Research, 29, 277–301.

Jung, M. J. (2011). Investor overlap and diffusion of disclosure practices. Review of Accounting Studies, 18, 167–206.

Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1994). Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17, 41–67.

King, R., Pownall, G., & Waymire, G. (1990). Expectations adjustments via timely management forecasts: Review synthesis and suggestions for further research. Journal of Accounting Literature, 9, 113–144.

Lakonishok, J., Lee, I., Pearson, N. D., & Poteshman, A. M. (2007). Option market activity. Review of Financial Studies, 20, 813–857.

Larker, D. F., & Rusticus, T. O. (2010). On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 49, 186–205.

Lawrence, A. (2013). Individual investors and financial disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56, 130–147.

Lee, C., & Swaminathan, B. (2000). Price momentum and trading volume. Journal of Finance, 55, 2017–2069.

Li, F. (2008). Annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45, 221–247.

Malmendier, U., Shanthikumar, D. (2009). Do security analysts speak in two tongues. Harvard University working paper.

Manela, A. (2014). The value of diffusing information. Journal of Financial Economics, 111, 181–199.

Mikhail, M. B., Walther, B. R., & Willis, R. H. (2007). When security analysts talk, who listens? The Accounting Review, 82, 1227–1253.

Miller, B. P. (2010). The effects of reporting complexity on small and large investor trading. The Accounting Review, 85, 2107–2143.

Petersen, M. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. The Review of Financial Studies, 22, 435–480.

Pool, V. K., Stoll, H. R., & Whaley, R. E. (2008). Failure to exercise call options: An anomaly and a trading game. Journal of Financial Markets, 11, 1–35.

Rogers, J. L. (2008). Disclosure quality and management trading incentives. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 1265–1296.

Rogers, J. L., Skinner, D. J., & Van Buskrik, A. (2009). Earnings guidance and market uncertainty. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48, 90–109.

Roll, R. (1977). An analytic valuation formula for unprotected American call options on stocks with known dividends. Journal of Financial Economics, 5, 251–258.

Solomon, D. (2011). Selective publicity and stock prices. Journal of Finance, 67, 599–637.

Soltes, E. (2009). News dissemination and the impact of the business press. University of Chicago working paper.

Sunder, S. V. (2003). Investor access to conference call disclosures: Impact of regulation fair disclosure on information asymmetry. University of Arizona working paper.

Tetlock, P. C. (2007). Giving content to investor sentiment: The role of media in the stock market. Journal of Finance, 62, 1139–1168.

Tetlock, P. C. (2010). Does public financial news resolve asymmetric information? Review of Financial Studies, 23, 3520–3557.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is based on my dissertation at the University of Chicago. I am extremely grateful to my dissertation committee: Christian Leuz (chair), Phil Berger, Doug Skinner, Jonathan Rogers, and Luigi Zingales for their many insightful comments and helpful discussions. I am also grateful to Patricia Dechow (editor), an anonymous referee, and Dan Amiram, Ray Ball, George Constantinides, Christopher Culp, Joseph Gerakos, Michael Gofman, Joao Granja, Avner Kalay, Zach Kaplan, Alan Moreira, Regina Wittenberg-Moerman, Gil Sadka, Alexi Savov, Catherine Schrand, Abbie Smith, and seminar participants at The University of Chicago, Columbia University, The University of Pennsylvania, MIT, New York University, University of Michigan, Dartmouth, Duke, The University of Utah, Northwestern University, and Cornell University for their helpful comments. I also want to thank the associates at Merrill Lynch and the SEC for the insightful discussions about the options market. I greatly appreciate the financial support of Columbia Business School. All errors are my own.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalay, A. Investor sophistication and disclosure clienteles. Rev Account Stud 20, 976–1011 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9317-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9317-z