Abstract

Purpose

Patient-reported outcome and experience measures (PROMs/PREMs) are well established in research for many health conditions, but barriers persist for implementing them in routine care. Implementation science (IS) offers a potential way forward, but its application has been limited for PROMs/PREMs.

Methods

We compare similarities and differences for widely used IS frameworks and their applicability for implementing PROMs/PREMs through case studies. Three case studies implemented PROMs: (1) pain clinics in Canada; (2) oncology clinics in Australia; and (3) pediatric/adult clinics for chronic conditions in the Netherlands. The fourth case study is planning PREMs implementation in Canadian primary care clinics. We compare case studies on barriers, enablers, implementation strategies, and evaluation.

Results

Case studies used IS frameworks to systematize barriers, to develop implementation strategies for clinics, and to evaluate implementation effectiveness. Across case studies, consistent PROM/PREM implementation barriers were technology, uncertainty about how or why to use PROMs/PREMs, and competing demands from established clinical workflows. Enabling factors in clinics were context specific. Implementation support strategies changed during pre-implementation, implementation, and post-implementation stages. Evaluation approaches were inconsistent across case studies, and thus, we present example evaluation metrics specific to PROMs/PREMs.

Conclusion

Multilevel IS frameworks are necessary for PROM/PREM implementation given the complexity. In cross-study comparisons, barriers to PROM/PREM implementation were consistent across patient populations and care settings, but enablers were context specific, suggesting the need for tailored implementation strategies based on clinic resources. Theoretically guided studies are needed to clarify how, why, and in what circumstances IS principles lead to successful PROM/PREM integration and sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patient-reported outcome and experience measures (PROMs/PREMs) are well established in research for many health conditions [1, 2], but barriers persist for implementing them in routine care. PROMs are reports of how patients feel and function that come directly from individuals with a health condition [3], while PREMs assess patient experiences of treatment (e.g., satisfaction with care) [4]. When used during care delivery, PROMs improve communication between clinicians and patients about symptoms and quality of life [5, 6], which may improve service use and survival [1, 2, 7,8,9,10,11]. Reviewing PROMs with patients during clinical visits can also increase satisfaction with care scores [12]. PREMs are commonly used as performance metrics to evaluate the quality of care delivered [13], but PROM-based performance metrics are a growing trend [14]. Before clinical benefits can be realized, however, PROMs/PREMs need to be implemented into care delivery.

There is wide variation in how PROMs/PREMs are implemented [15, 16] and in the resulting impact on processes and outcomes of care [1, 2, 5, 6]. Prior research has documented the limited uptake of PROMs/PREMs and barriers to their implementation in routine care settings [17,18,19,20,21]. Implementation science (IS) offers a potential way forward, but its application has been limited for PROMs/PREMs. IS is the systematic study of methods to integrate evidence-based practices and interventions into care settings [22, 23]. IS aims to make the process of implementation more systematic, resulting in a higher likelihood that health innovations like PROMs/PREMs are adopted in clinics.

Part of IS’s appeal are the theories and frameworks guiding the translation process from research to practice [24,25,26], but there are dozens focused on health care [26]. IS frameworks and theories draw on diverse academic disciplines including psychology, sociology, and organizational science, and therefore differ in assumptions about the primary drivers of implementation processes and potential explanatory power. Frameworks identify and categorize key barriers and enablers, while theories tend to have more explanatory power because they specify practical steps in translating research evidence into practice. IS is still an emerging field, and descriptive frameworks are the most common, as outlined in Nilsen’s typological classification of theoretical approaches [24].

In addition to explanatory features, IS frameworks and theories may also provide a menu of potential solutions to barriers called “implementation strategies.” These strategies are actions purposively developed to overcome barriers that can be tailored to the local context [27, 28]. Figure 1 shows how implementation strategies are used to influence proximal mediators such as clinician self-efficacy for using PROM/PREMs, which impact IS outcomes for PROM/PREM implementation (e.g., Proctor’s outcomes [29]), and in turn improve clinical and health services outcomes.

Our paper is organized into three sections. First, we describe and compare IS frameworks used in four case studies. We then summarize cross-study findings on the barriers, enablers, implementation strategies, and evaluation approaches. We also derive example metrics specific to evaluating PROM/PREM implementation initiatives to support standardization. Finally, we consider the implications of these findings for future research and practice.

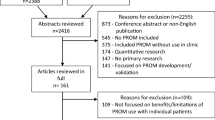

We compare four case studies of PROMs/PREMs implementation (see Fig. 2) that draw on established IS frameworks or theories (each case study has a stand-alone paper in this issue: [30,31,32,33]). Three case studies implemented PROMs for monitoring symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and/or health-related quality of life: (1) pain clinics in Canada [30]; (2) oncology clinics in Australia [31]; and (3) pediatric/adult clinics for chronic conditions in the Netherlands [32]. The fourth case study is planning PREMs implementation in primary care clinics in Canada [33].

Theoretical approaches used in case studies

Across case studies, five well-established IS frameworks or theories widely used in health care settings were applied (Table 1).

Three case studies [30, 32, 33] used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [34, 35]. CFIR was developed from constructs identified in earlier frameworks and is widely used [35]. Its 39 constructs are organized into five multilevel domains: the intervention itself (e.g., PROMs/PREMs), outer setting (e.g., national policy context), inner setting (e.g., implementation climate in clinics), characteristics of individuals involved (e.g., clinic teams), and the implementation process. CFIR has a tool available to match barriers to implementation strategies (available at www.cfirguide.org), which was used prospectively for planning PREMs implementation [33] and retrospectively for assessing implementation of a PROMs portal for chronic conditions [32].

The case study in an integrated chronic pain care network [30] combined CFIR with the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [36,37,38] to identify barriers and enablers for implementing PROMs. TDF is grounded in a psychology perspective on behavior change at the clinician level. Fourteen domains describe constructs such as clinician knowledge, skills, and perceptions.

The case study in oncology clinics [31] used the integrated Promoting Action Research in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework [39,40,41,42]. i-PARIHS’ key construct of facilitationFootnote 1 is the “active ingredient” driving successful implementation, for example, an implementation support person working with clinics to identify and overcome barriers. In its most recent development [40], i-PARIHS’ three multilevel predictors include: (1) the innovation (ways stakeholders perceive and adapt innovations like PROMs/PREMs to align with local priorities); (2) recipients (how individuals and communities of practice influence uptake of new knowledge in clinics); and (3) context (inner context such as clinic culture and outer context such as the wider health and policy system). The i-PARIHS facilitator’s toolkit [42] offers pragmatic guidance for supporting implementation in clinics.

The case study implementing PREMs in primary care clinics [43] combined CFIR with the Knowledge to Action (KTA) model [43, 44] and Normalization Process Theory (NPT) [45, 46]. KTA is a process model describing practical steps or stages in translating research into practice, with core concepts of knowledge creation and action. The action cycle is most applicable to PROM/PREM implementation, with steps for identifying the problem and selecting and enacting appropriate knowledge for addressing the problem.

Normalization Process Theory (NPT) [45, 46], developed from sociological theory, describes mechanisms of how an innovation becomes routinized. NPT’s focus is on what people actually do, rather than their intentions, by focusing on how the “work” of an innovation (such as using PROMs/PREMs in clinical practice) becomes normalized. NPT outlines four mechanisms driving implementation processes: coherence/sense-making (What is the work?), cognitive participation (Who does the work?), collective action (How do people work together to get the work done?), and reflexive monitoring (How are the effects of the work understood?).

Table 1 shows that there is some overlap of core constructs across implementation frameworks and theories and some unique features. Frameworks and theories typically emphasize particular constructs. For example, the i-PARIHS framework highlights the role of a facilitator (implementation support person) as a core construct. The oncology case study [31] that used i-PARIHS was the only one to employ a dedicated facilitator across the full implementation cycle; although the three other case studies did use implementation support teams for shorter durations. The case study in pain clinics [30] had a priori identified clinician engagement with PROMs as a key issue and chose TDF as their framework because it describes barriers specifically at the clinician level.

The case study at the pre-implementation stage for PREMs in primary care [33] drew on KTA and NPT, which both emphasize steps in the implementation process instead of describing barriers. As we later suggest, implementation theory that hypothesizes mechanisms of change (such as NPT) may be a useful guide for developing overarching strategies across stages of implementation. An overarching theoretical approach could then be supplemented with consideration of context-specific barriers and enablers for PROMs/PREMs through multilevel frameworks such as CFIR or i-PARIHS.

Barriers and enablers in case studies

Frameworks described in the prior section are based on a foundation of barriers and enablers. The distinction between whether a concept is labeled as a barrier or enabler is a judgment based on the framework or theory being used and stakeholder perceptions [22, 28]. The label of barrier or enabler shapes the implementation approach considerably. For example, if lack of PROM/PREM technology is labeled as a barrier, an implementation strategy such as developing software with stakeholder input will be used. If existing technology is labeled as an enabler, the implementation team can tailor training and examples to the specific software.

Table 2 shows that the four case studies consistently described implementation barriers of technology, stakeholder uncertainty about how or why to use PROMs/PREMs, stakeholder concerns about negative impacts of PROM/PREM use, and competing demands from established clinical workflows.

For technology, PROMs/PREMs not being integrated within electronic health record systems was repeatedly identified as a major barrier. Additional technology barriers included PROM collection systems that were difficult to use or access, and third-party systems requiring a separate login.

Stakeholder knowledge and perceptions were also identified as consistent barriers. Clinicians noted a knowledge barrier of being unsure how to interpret PROM responses and discuss them with their patients. There were also concerns that PROM use would lead to increases in workload and visit length, and the potential to decrease satisfaction with care. Roberts’ oncology clinic case study [31] also encountered clinics with prior negative experiences with innovations.

Clinical workflow barriers included entrenched workflow, competing priorities during limited clinic time, and unique workflow in every clinic, suggesting implementation strategies that work in some clinics or settings may not work in others. Less common barriers included resource gaps for treating and referring patients for symptoms detected by PROMs (oncology clinic case study) and confidentiality concerns for PROMs/PREMs (pain clinic case study).

Figure 3 shows that enablers varied more across case studies than barriers, suggesting that solutions were being tailored to each clinic and its resources (inner context). Common enabling factors included designing PROM/PREM technology systems to be easy for clinicians to use and enabling automatic access to PROM results for use at point-of-care. More unique enablers capitalized on local resources, such as peer champions, availability of a nurse scientist to provide long-term implementation support in an oncology clinic, and a research team working with a health system to create a pain PROM business plan and move resources (including money) to clinics. Two case studies were enabled with research grant support.

Implementation strategies in case studies

Case study authors matched PROM/PREM barriers and enablers encountered in clinics directly to specific implementation strategies. Figure 4 shows that implementation strategies changed during pre-implementation, implementation, and post-implementation stages and were influenced by contextual factors. During pre-implementation, case studies engaged stakeholders and clinic leaders, and assessed barriers, enablers, PROM/PREM needs, and workflow. They also engaged clinic teams to develop tailored implementation strategies. During the implementation stage, all case studies trained clinic teams on using and interpreting PROMs/PREMs and provided onsite assistance for technology and workflow. Support ranged from low intensity with one training session and a few support visits to high-intensity facilitation conducted onsite and long term (> 6 months). The pain clinic case study [30] also developed strategies to increase clinic teams’ perceptions of acceptability of PROMs through a media campaign for clinic teams. Post-implementation, all case studies continued contact with clinics, typically through visits. Three case studies also used audit and feedback where dashboard reports were fed back to clinics about their PROM/PREM completion rates. If completion rates were low, additional support was provided to clinics to identify and overcome new or ongoing barriers, suggesting that post-implementation support may be key to sustaining PROM/PREMs in clinics.

Evaluating PROM/PREM implementation initiatives

Three case studies [30,31,32] used aspects of Proctor’s IS outcomes [29] to evaluate PROMs and one case study [33] used the RE-AIM framework [47, 48] to evaluate PREMs, but the degree of application and operationalization were inconsistent. Table 3 shows that Proctor’s IS framework and RE-AIM have overlapping concepts for reach/penetration, adoption, and sustainability/ maintenance. Unique to Proctor’s list are acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, and cost [29]. Unique to RE-AIM are effectiveness and “implementation” [47, 48].

Case studies used a range of 2–6 evaluation constructs, typically obtained with qualitative methods. Given the use of Proctor’s outcome framework [29] in three out of four case studies, it may be a viable method to standardize PROM/PREM evaluation. Its constructs of acceptability and appropriateness of PROMs/PREMs for a specific clinic were the most common evaluation outcomes, and were assessed with stakeholder interviews. The remaining six Proctor outcomes were used less frequently, in part due to their applicability in later stages of implementation.

To support standardizing evaluation metrics, we derived Table 4 to describe how Proctor’s IS outcomes [29] can be evaluated specifically for PROM/PREM implementation initiatives. Table 4 makes an important distinction that evaluation metrics are different for perceptions of the innovation (PROMs/PREMs) vs. implementation effectiveness. For example, innovation feasibility for PROMs/PREMs may involve a pilot study of tablet vs. paper administration, but an example metric for implementation feasibility is the percentage of clinics completing PROM/PREM training.

Table 4 shows that the constructs of adoption, reach/penetration, fidelity, and sustainability can be measured in terms of engagement rates and milestone achievements at the clinic level. For example, innovation fidelity can be assessed as the percentage of clinicians who review PROMs/PREMs with patients as intended. The FRAME framework [49] can be used for reporting adaptions to interventions/innovations. However, implementation fidelity can be assessed as the extent to which recommended implementation strategies were adhered to and how and why clinics adapted implementation strategies. The Fidelity Framework developed by the National Institutes of Health’s Behavioral Change Consortium [50] recommends reporting on five implementation fidelity domains (study design, training, delivery, receipt, and enactment). Assessment of innovation costs may include personnel and clinic and patient time necessary for completing and reviewing PROMs/PREMs that can be assessed via observation or economic evaluation methods [51]. Implementation strategy costs can be assessed through tools such as the “Cost of Implementing New Strategies” (COINS) [52].

As Table 4 illustrates, collecting evaluation data requires careful planning and resource allocation at the start of PROMs/PREMs implementation efforts, but evaluation data are critical for gauging success, ongoing monitoring, and making improvements. Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 also show that the implementation process and evaluation metrics are influenced by contextual factors (inner and outer context, individual involved, and characteristics of the innovation), which can be assessed to help explain evaluation results. Reviews of IS scales [53, 54] include questionnaires assessing contextual factors, but they may lack psychometric and validity evidence. An alternative is to assess contextual factors with stakeholder interviews.

Discussion

This paper makes several important contributions to the literature. Our comparison of four case studies enabled us to identify commonalities and differences in barriers, enablers, implementation strategies, and evaluation methods for implementing PROMs/PREMs across a range of patient populations and care settings. Below we describe lessons learned, recommendations, and areas in need of future research.

Relevance of IS approaches for PROMs/PREMs implementation

Our cross-study analysis demonstrates that IS approaches are largely harmonious with PROMs/PREMs implementation, although no single framework or theory fully captures their nuances. Multilevel frameworks and theories are necessary for PROM/PREM implementation given its complexity. IS theoretical approaches are not prescriptive but can be used flexibly, potentially in combinations, to suit specific contexts; multiple frameworks were used in two case studies presented here to emphasize different domains.

CFIR was the most commonly used framework, applied in three case studies during pre-implementation and implementation stages. CFIR is fairly comprehensive for categorizing barriers and enablers, but it does not specify mechanisms by which strategies might improve implementation effectiveness. Given the broad nature of CFIR, the pain clinic case study [30] found CFIR captured more barriers than TDF for clinician knowledge and perceptions. The case study by van Oers et al. [32] noted difficulty in operationalizing concepts in CFIR because of overlapping subdomains and difficulty in classifying PROM/PREM characteristics (e.g., item content, psychometric properties) in the subdomain “characteristics of the innovation,” suggesting modifications to CFIR or additional frameworks may be needed to capture PROM/PREM nuances. The availability of CFIR’s tool for matching implementation strategies to barriers also contributed to its perceived utility, although the usefulness of the matching tool in practice was unclear.

Of the widely used IS frameworks and theories described in this paper, Normalization Process Theory (NPT) [45, 46] is distinct in proposing mechanisms for sustained uptake of innovations. NPT’s core constructs of coherence/sense-making, cognitive participation, collective action, and reflexive monitoring overlap with domains from other IS frameworks and implementation strategies used in case studies (see Table 5). The applicability of these general constructs to specific PROMs/PREMs implementation efforts should be tested in future studies. If they prove to be robust in new settings, these potential drivers of implementation could inform a more universal strategy for increasing the uptake of PROMs/PREMs in routine care.

We recommend choosing an IS framework or theory based on fit for purpose [24, 25]. Research focused on identifying and categorizing barriers and enablers may benefit from descriptive frameworks like i-PARIHS or CFIR, which also provide lists of evidence-based implementation strategies. Research describing translation processes could use a process model like KTA or implementation theory like NPT. All case studies combined descriptive frameworks or process models/theory with evaluation frameworks. Existing implementation toolkits can aid in decisions on which frameworks, theories, and implementation strategies might be appropriate for specific PROM/PREM projects [55, 56].

Consistent barriers, context-specific enablers, and tailored implementation strategies

A key finding from our cross-study analysis was that barriers were consistent across populations and care settings, but enablers were context specific. Barriers included technology limitations, uncertainty about ease and benefit of using PROMs/PREMs, concerns about potential negative impacts, and competing demands within established clinical workflows. These barriers are also consistent with existing literature [18,19,20,21], including ISOQOL’s PROM User Guides [20], suggesting that clinics and implementation teams should include these known barriers in their pre-implementation planning process.

While barriers in case studies were consistent, an important finding from our analysis was that enablers were context specific and based on local clinic resources. The observed variation in PROM/PREM enablers indicates the potential for tailored solutions for clinics. A common enabling factor was an existing PROM/PREM technology system with automated features. More unique enablers capitalized on local resources, such as providing clinics with implementation funding, media campaigns, and having physician champions teach part of PROM/PREM training sessions. Future research should examine whether co-designing PROMs/PREMs implementation strategies with clinics improves implementation effectiveness and patient outcomes.

The variation we observed in implementation strategies may have more to do with implementation stage and local clinic needs than particular care settings or populations. For example, all case studies found that engaging clinicians during development of implementation strategies was critical; but the PREM case study [33] also found it useful to engage quality improvement specialists because that was an available resource. Manalili et al. [33] noted that clinics may need support in building capacity for quality improvement before PROMs/PREMs can be introduced. Ahmed et al. [30] used a standardized process called intervention mapping [57, 58] to map barriers to evidence-based strategies.

Common PROM/PREM implementation strategies in case studies matched most of Powell and colleagues’ “Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change” (ERIC) [27], suggesting there are critical implementation strategies that need to be conducted regardless of setting or population (e.g., training clinic teams and providing implementation support). For example, Skovlund et al. [59] developed a PROM training tool for clinicians that may be useful as an implementation strategy. Future research should determine key implementation strategies that enable higher uptake of PROMs/PREMs in clinics.

Consistent implementation strategies across case studies included providing technology and workflow support to clinics, but it ranged from low to high intensity. Roberts et al. [31] found that having a dedicated implementation support role (nurse-trained scientist) was critical for maintaining momentum during pre-implementation and implementation phases in cancer clinics. Across case studies, clinics needed flexibility and support in adapting their workflow, but there is no corollary listed in the ERIC strategies. We agree with Perry et al. [60] who recommended adding workflow assessment and care redesign to the ERIC [27] list based on their empirical data. Future research is needed on the optimal level and intensity of implementation support for successful PROM/PREM implementation.

Case studies were inconsistent in the level of detail provided about implementation strategies, which may inhibit replication. We recommend PROM/PREM IS studies follow the “Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies” (StaRI) guidelines [61]. A framework called “Action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT)” [62] may be useful as a reporting tool for describing PROM/PREM implementation strategies. Leeman et al. [28] also recommend defining implementation strategies a priori and specifying who will enact the strategy (actor) and the level and determinants that will be targeted (action targets).

Need for consistent and robust measurement in IS evaluation

In the case studies, we highlighted inconsistencies in IS evaluation. We therefore developed IS metrics specific to PROM/PREM implementation to support reporting and standardization (Table 4). These metrics are not questionnaires, but rather percentages of how many clinics achieve milestones like completing implementation activities. Our metrics advance the field of IS by being one of the first to describe separate metrics for evaluating perceptions of a health innovation vs. implementation effectiveness. Future research is needed to build validity and reliability evidence for these metrics.

A related issue is that many IS questionnaires assessing Proctor’s constructs and contextual factors lack psychometric testing, validity and reliability evidence, and short forms. Systematic reviews of IS questionnaires [53, 54, 63,64,65] show that information on reliability is unavailable for half of IS instruments and > 80% lacked validity evidence [54]. IS questionnaires tend to be long (30+ items), so their utility in busy clinics may be limited [66]. They also have unclear relevance for PROMs/PREMs implementation. With notable exceptions [65, 67, 68], few IS scales have published psychometric properties [54]. For example, one exception with published classical test theory data developed short forms to assess acceptability, appropriateness, and perceived feasibility across implementation initiatives [68]. These generic short forms were used in the pain clinic case study [30], and they are being tested in cancer care PROM implementation in the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s IMPACT consortium [69].

It is unknown how many IS questionnaires meet psychometric standards and whether new instruments need to be developed for PROMs/PREMs implementation and thus, scale reviews specific to PROMs/PREM implementation are needed. Funding agencies interested in PROM/PREM implementation should consider requesting proposals to generate this critical psychometric evidence to ensure standardization and replicability. Ideally, if shorter versions of existing IS questionnaires could be developed, comparisons with health care IS studies outside of PROMs/PREMs may be possible.

Why implementation theory is needed

Increasing the use of IS in PROM/PREM implementation studies will help advance our collective understanding of how, why, and in what circumstances IS frameworks and implementation strategies produce successful implementation (or not). Mechanisms of change may differ between active implementation and sustainability, and even between PROMs and PREMs. Future research should explicitly test hypothesized pathways through which implementation strategies exert their effects on implementation outcomes, care delivery, and patient outcomes. Figure 1 shows that mediators (or potentially moderators) in these pathways are contextual factors. Future research is needed to determine which contextual factors matter for PROM/PREM implementation and how best to assess them.

Pathways linking strategies with IS outcomes and clinical outcomes can be tested with stepped wedge designs, pragmatic trials, and theory-driven mixed methods such as realist evaluation [6, 70,71,72]. Realist evaluation seeks to understand how context shapes the mechanisms through which a health care innovation works. Realist evaluation recognizes that complex interventions (such as those informed by IS) are rarely universally successful, because clinic context plays a significant role in shaping their uptake and impact. This is consistent with our finding that PROM/PREM clinic enablers had more variation than barriers in case studies. While RCTs and pragmatic trials are useful to evaluate the net or average effect of an intervention, realist evaluation could help clarify why specific implementation strategies work in some contextual conditions but not others [6, 70,71,72], and could complement other IS approaches. Research on the “how” and “why” of implementation processes will help move the field beyond simply identifying barriers and enablers of PROMs/PREMs implementation, to proactively designing and comparing implementation strategies.

Conclusion

In four case studies, IS frameworks were used to systematize barriers to PROM/PREM implementation, to develop implementation support strategies for clinic teams, and to evaluate implementation effectiveness. Barriers to PROM/PREM implementation were remarkably consistent across patient populations and care settings, suggesting that implementation strategies addressing contextual factors may have wide-reaching impact on implementation effectiveness. Flexibility in promoting clinic-specific enablers was also highlighted, as was a need for consistency in evaluating PROM/PREM implementation effectiveness. Theoretically guided studies are needed to clarify how, why, and in what circumstances IS approaches lead to successful PROM/PREM integration and sustainability.

Notes

We use the term “facilitators” in this paper series to designate the implementation support person working with clinics, rather than the classic use of the word in IS to mean enablers, such as clinic resources.

References

Kotronoulas, G., Kearney, N., Maguire, R., Harrow, A., Di Domenico, D., Croy, S., et al. (2014). What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(14), 1480–1501.

Boyce, M. B., & Browne, J. P. (2013). Does providing feedback on patient-reported outcomes to healthcare professionals result in better outcomes for patients? A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 22(9), 2265–2278.

Food, U. S., & Administration, D. (2019). Patient-focused drug development: Methods to identify what is important to patients: Draft guidance for industry, food and drug administration staff, and other stakeholders. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Kingsley, C., & Patel, S. (2017). Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. British Journal of Anaesthesia Education, 17(4), 137–144.

Yang, L. Y., Manhas, D. S., Howard, A. F., & Olson, R. A. (2018). Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: A systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(1), 41–60.

Greenhalgh, J., Gooding, K., Gibbons, E., Dalkin, S., Wright, J., Valderas, J., et al. (2018). How do patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) support clinician-patient communication and patient care? A realist synthesis. Journal of Patient Reported Outcomes, 2, 42.

Basch, E., Deal, A. M., Kris, M. G., Scher, H. I., Hudis, C. A., Sabbatini, P., et al. (2016). Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 34, 557–565.

Ediebah, D. E., Quinten, C., Coens, C., Ringash, J., Dancey, J., Zikos, E., et al. (2018). Quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: A pooled analysis of individual patient data from Canadian cancer trials group clinical trials. Cancer, 124, 3409–3416.

Berg, S. K., Thorup, C. B., Borregaard, B., Christensen, A. V., Thrysoee, L., Rasmussen, T. B., et al. (2019). Patient-reported outcomes are independent predictors of one-year mortality and cardiac events across cardiac diagnoses: Findings from the national DenHeart survey. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 26(6), 624–663.

Raffel, J., Wallace, A., Gveric, D., Reynolds, R., Friede, T., & Nicholas, R. (2017). Patient-reported outcomes and survival in multiple sclerosis: A 10-year retrospective cohort study using the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale-29. PLoS Medicine, 14(7), e1002346.

Howell, D., Li, M., Sutradhar, R., Gu, S., Iqbal, J., O'Brien, M. A., et al. (2020). Integration of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for personalized symptom management in “real-world” oncology practices: A population-based cohort comparison study of impact on healthcare utilization. Supportive Care in Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05313-3. (in press).

Freel, J., Bellon, J., & Hanmer, J. (2018). Better physician ratings from discussing PROs with patients. New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst. Retrieved June 20, 2018, from https://catalyst.nejm.org/ratings-patients-discussing-pros/.

Beattie, M., Murphy, D. J., Atherton, I., & Lauder, W. (2015). Instruments to measure patient experience of healthcare quality in hospitals: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 4, 97.

Stover, A. M., Urick, B. Y., Deal, A. M., Teal, R., Vu, M. B., Carda-Auten, J., et al. (2020). Performance measures based on how adults with cancer feel and function: Stakeholder recommendations and feasibility testing in six cancer centers. JCO Oncology Practice, 16(3), e234–e250.

Hsiao, C. J., Dymek, C., Kim, B., et al. (2019). Advancing the use of patient-reported outcomes in practice: Understanding challenges, opportunities, and the potential of health information technology. Quality of Life Research, 28(6), 1575–1583.

Rodriguez, H. P., Poon, B. Y., Wang, E., et al. (2019). Linking practice adoption of patient engagement strategies and relational coordination to patient-reported outcomes in accountable care organizations. Milbank Quarterly, 97(3), 692–735.

Porter, I., Gonalves-Bradley, D., Ricci-Cabello, I., Gibbons, C., Gangannagaripalli, J., Fitzpatrick, R., et al. (2016). Framework and guidance for implementing patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: Evidence, challenges and opportunities. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 5(5), 507–519.

van Egdom, L. S. E., Oemrawsingh, A., Verweij, L. M., Lingsma, H. F., Koppert, L. B., Verhoef, C., et al. (2019). Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in clinical breast cancer care: A systematic review. Value in Health, 22(10), 1197–1226.

Foster, A., Croot, L., Brazier, J., Harris, J., & O'Cathain, A. (2018). The facilitators and barriers to implementing patient reported outcome measures in organisations delivering health related services: A systematic review of reviews. Journal of Patient Reported Outcomes, 2, 46.

Snyder, C. F., Aaronson, N. K., Choucair, A. K., Elliott, T. E., Greenhalgh, J., Halyard, M. Y., et al. (2012). Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: A review of the options and considerations. Quality of Life Research, 21(8), 1305–1314.

Antunes, B., Harding, R., & Higginson, I. J. (2014). Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: A systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliative Medicine, 28, 158–175.

Hull, L., Goulding, L., Khadjesari, Z., Davis, R., Healey, A., & Bakolis, I. (2019). Designing high-quality implementation research: Development, application, feasibility and preliminary evaluation of the implementation science research development (ImpRes) tool and guide. Implementation Science, 14, 80.

Mitchell, S. A., & Chambers, D. (2017). Leveraging implementation science to improve cancer care delivery and patient outcomes. Journal of Oncology Practice, 13(8), 523–529.

Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models, and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53.

Tabak, R. G., Khoong, E. C., Chambers, D. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2012). Bridging research and practice models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(3), 337–350.

Moullin, J. C., Sabater-Hernandez, D., Fernandez-Llimos, F., & Benrimoj, S. I. (2015). A systematic review of implementation frameworks of innovations in healthcare and resulting generic implementation framework. Health Research Policy Systems, 13, 16.

Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., et al. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10, 21.

Leeman, J., Birken, S. A., Powell, B. J., Rohweder, C., & Shea, C. M. (2017). Beyond “implementation strategies”: Classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implementation Science, 12, 125.

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., et al. (2010). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76.

Ahmed, S., Zidarov, D., Eilayyan, O., & Visca, R. Prospective application of implementation science theories and frameworks to use PROMs in routine clinical care within an integrated pain network. Under review at Quality of Life Research as part of this supplement.

Roberts, N., Janda, M., Stover, A. M., Alexander, K., Wyld, D., Mudge, A. Using the Integrated Promoting Action Research in Health Services (iPARIHS) Framework to evaluate implementation of Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) into routine care in a medical oncology outpatient department. Under review at Quality of Life Research as part of this supplement.

van Oers, H. A., Teela, L., Schepers, S. A., Grootenhuis, M. A., & Haverman, L. A retrospective assessment of the KLIK PROM portal implementation using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Under review at Quality of Life Research as part of this supplement.

Manalili, K., & Santana, M. J. Using implementation science to inform integration of electronic patient-reported experience measures (ePREMs) into healthcare quality improvement. Under review at Quality of Life Research as part of this supplement.

Damschroder, L., Aron, D., Keith, R., Kirsh, S., Alexander, J., & Lowery, J. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50.

Kirk, A. M., Kelley, C., Yankey, N., Birken, S. A., Abadie, B., & Damschroder, L. (2016). A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science, 11, 72.

Mosavianpour, M., Sarmast, H. H., Kissoon, N., & Collet, J. P. (2016). Theoretical domains framework to assess barriers to change for planning health care quality interventions: A systematic literature review. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 9, 303–310.

Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., et al. (2017). A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science, 12, 77.

Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7, 37.

Rycroft-Malone, J. (2004). The PARIHS framework—a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 19(4), 297–304.

Harvey, G., & Kitson, A. (2016). PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science, 11(33), 1–13.

Stetler, C. B., Damschroder, L. J., Helfrich, C. D., & Hagedorn, H. J. (2011). A guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implementation Science, 6, 99.

Harvey, G., & Kitson, A. (2015). Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: A facilitation guide. London: Routledge.

Graham, I., Logan, J., Harrison, M., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., et al. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education of Health Professionals, 26, 13–24.

Field, B., Booth, A., Ilott, I., & Gerrish, K. (2014). Using the knowledge to action Framework in practice: A citation analysis and systematic review. Implementation Science, 9, 172.

May, C., & Finch, T. (2009). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554.

May, C., Finch, T., & Rapley, T. (2020). Normalization process theory. In S. Birken & P. Nilsen (Eds.), Handbook of implementation science (pp. 144–167). Glos: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Glasgow, R., Vogt, T., & Boles, S. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327.

Glasgow, R. E., Harden, S. M., Gaglio, B., Rabin, B., Smith, M. L., et al. (2019). RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 64.

Wiltsey Stirman, S., Baumann, A. A., & Miller, C. J. (2019). The FRAME: An expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 14, 58.

Borrelli, B. (2011). The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71, S52–S63.

Eisman, A. B., Kilbourne, A. K., Dopp, A. R., Saldana, L., & Eisenberg, D. (2020). Economic evaluation in implementation science: Making the business case for implementation strategies. Psychiatry Research, 283, 112433.

Saldana, L., Chamberlain, P., Bradford, W. D., Campbell, M., & Landsverk, J. (2014). The Cost of Implementing New Strategies (COINS): A method for mapping implementation resources using the stages of implementation completion. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 177–182.

Khadjesari, Z., Hull, L., Sevdalis, N., & Vitoratou, S. (2017). Implementation outcome instruments used in physical healthcare settings and their measurement properties: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 2, 36.

Lewis, C. C., Fischer, S., Weiner, B. J., Stanick, C., Kim, M., & Martinez, R. G. (2015). Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implementation Science, 10, 155.

Hull, L., Goulding, L., Khadjesari, Z., et al. (2019). Designing high-quality implementation research: development, application, feasibility and preliminary evaluation of the implementation science research development (ImpRes) tool and guide. Implementation Science, 14, 80.

Gerke, D., Lewis, E., Prusaczyk, B., Hanley, C., Baumann, A., & Proctor, E. (2017). Implementation outcomes. St. Louis, MO: Washington University. Eight toolkits related to Dissemination and Implementation. Retrieved from https://sites.wustl.edu/wudandi. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

Eldredge, L. K. B., Markham, C. M., Ruiter, R. A., et al. (2016). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach. San Francisco: John.

Fernandez, M. E., Ten Hoor, G. A., van Lieshout, S., Rodriguez, S. A., Beidas, R. S., et al. (2019). Implementation mapping: Using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 158.

Skovlund, P. C., Ravn, S., Seibaek, L., Vind Thaysen, H., Lomborg, K., et al. (2020). The development of PROmunication: A training-tool for clinicians using patient reported outcomes to promote patient-centred communication in clinical cancer settings. Journal of Patient Reported Outcomes, 4, 10.

Perry, C. K., Damschroder, L. J., Hemler, J. R., Woodson, T. T., Ono, S. S., & Cohen, D. J. (2019). Specifying and comparing implementation strategies across seven large implementation interventions: A practical application of theory. Implementation Science, 14, 32.

Pinnock, H., Barwick, M., Carpenter, C. R., Eldridge, S., Grandes, G., Griffiths, C. J., et al. (2017). Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) statement. British Medical Journal, 356, i6795.

Presseau, J., McCleary, N., Lorencatto, F., Patey, A. M., Grimshaw, J. M., & Francis, J. J. (2019). Action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT): A framework for specifying behaviour. Implementation Science, 14, 102.

Clinton-McHarg, T., Yoong, S. L., Tzelepis, F., et al. (2016). Psychometric properties of implementation measures for public health and community settings and mapping of constructs against the consolidated framework for implementation research: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 11, 148.

Fernandez, M. E., Walker, T. J., Weiner, B. J., Calo, W. A., Liang, S., Risendal, B., et al. (2018). Developing measures to assess constructs from the inner setting domain of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science, 13, 52.

Chaudoir, S. R., Dugan, A. G., & Barr, C. H. (2013). Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: A systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implementation Science, 8, 22.

Martinez, R. G., Lewis, C. C., & Weiner, B. J. (2014). Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implementation Science, 9, 118.

Weiner, B. J., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C., Powell, B. J., Dorsey, C. N., Clary, A. S., et al. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12, 108.

Shea, C. M., Jacobs, S. R., Esserman, D. A., et al. (2017). Organizational readiness for implementing change: A psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implementation Science, 9, 7.

National Cancer Institute. (2019). Improving the Management of symPtoms during And following Cancer Treatment (IMPACT) Consortium. Retrieved November 15, 2019, from https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/impact/.

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic Evaluation, London: Sage

Prashanth, N. S., Marchal, B., Devadasan, N., Kegels, G., & Criel, B. (2014). Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: A realist evaluation of a capacity building programme for district managers in Tumkur, India. Health Research Policy and Systems, 12, 42.

Wong, G., Westhorp, G., Manzano, A., Greenhalgh, J., Jagosh, J., & Greenhalgh, T. (2016). RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Medicine, 14, 96.

Acknowledgements

This paper was reviewed and endorsed by the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) Board of Directors as an ISOQOL publication and does not reflect an endorsement of the ISOQOL membership. Portions of this work were presented at the International Society for Quality of Life research (ISOQOL) conference as workshops (Dublin, Ireland in October, 2018 and San Diego, CA, USA in October, 2019) and as a symposium (Prague, Czech Republic in October 2020).

Funding

Angela M. Stover: Work supported in part by UNC Provost Award H2245, UNC Lineberger’s University Cancer Research Fund, and R25CA171994. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of supporting institutions. Caroline M. Potter Receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Applied Research Collaboration for Oxford and the Thames Valley (ARC OTV) at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. This study made use of resources funded through the Gillings School of Global Public Health Nutrition Obesity Research Center (NIDDK funded; P30 DK56350) and the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCI funded; P30-CA16086): the Communication for Health Applications and Interventions (CHAI) Core.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from participants in case studies.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the ISOQOL PROMs/PREMs in Clinical Practice Implementation Science Work Group are listed in the Online Appendix of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stover, A.M., Haverman, L., van Oers, H.A. et al. Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Qual Life Res 30, 3015–3033 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02564-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02564-9