Abstract

Purpose

Cancer patients are increasingly involved in decision-making processes. Hence, clinicians need to inform patients about the risks and benefits of different treatment options in order for patients to make well informed decisions. The aim of this review is to determine the effects of methods of communicating prognostic information about (1) disease progression (survival, progression, recurrence and remission), (2) side effects and complications and (3) health-related quality of life (HRQL) on cognitive, affective and behavioral outcomes in cancer patients.

Methods

A literature search was performed to select articles that were published up to November 2019 and that examined verbal and/or visual risk communication interventions in an oncological clinical setting.

Results

The search yielded 14,875 studies; 28 studies were ultimately included. For disease progression information, we found that framing affects treatment choice. Furthermore, limiting the amount of progression information in a graphical display could benefit patients’ understanding of risks and benefits. For prognostic information about side effects and complications, precise and defined risk information was better understood than information presented in words. When displaying HRQL data, no consensus was found on which graph type to use.

Conclusion

Great heterogeneity in the results and methodology and in the compared communication formats precluded us from drawing any further conclusions. Practical implications for clinicians are to consider the effects that different types of framing might have on the patient and to not rely exclusively on words to describe risks, but rather include at least some form of numbers or visualization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In daily clinical practice, many decision making situations occur in which there is no ‘single best treatment option’, since either the medical scientific evidence on the benefit–harm ratio of the options is insufficient, or the ratio is dependent on patients’ values [1]. There is increasing consensus that in these situations, the patient and clinician need to work together and determine what is best for the patient, a process called shared decision-making (SDM) [2, 3].

The clinician however remains responsible for the transfer of probabilistic information to the patient, which is an important step in shared decision-making. If there are multiple treatment options, patients should receive information about disease progression or survival, the risk of side effects and complications, and the impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL) for each option. It is of importance that patients understand the risks and benefits [4], only then can the decision-making process result in the best choice for this particular patient.

However, research shows that correct understanding of relevant outcome information is by no means always achieved in cancer care. For example, studies have shown that breast cancer patients do not fully understand probabilistic information as presented by the clinician [5, 6]. In the case of rectal cancer, only a few patients were found to be able to correctly estimate probabilistic information on treatment outcomes [7]. Clinicians can use different methods to communicate risks, for example, by using words or numbers, by using different types of graphic displays, or by framing the information negatively or positively (in terms of survival or mortality). Based on the review by Zipkin, et al., recommendations are available for risk communication in health care, such as avoiding the exclusive use of qualitative risk descriptors (such as ‘many’, or ‘high’), supplementing bar charts or icon arrays to numerical risks, and recognizing that framing and the use of relative risk reductions (RRRs) (see Table 1) influences decision making [8]. However, to date, we do not know to what extent these recommendations apply to the specific context of making decisions about cancer treatment. These are difficult decisions because of the complexity of most treatments. Moreover, the life-threatening nature of the disease induces many emotions [9], which might affect information processing and thus the decision-making process [10]. Furthermore, we do not know how these recommendations might differ for different types of probabilistic information: disease progression, side effects and complication or HRQL [8].

The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the evidence on the effect of different ways of communicating treatment-related disease progression, side effects and complications and HRQL risk information to cancer patients who have to decide about treatment. Therefore, the effects of different communication methods will be evaluated on three levels: cognitive outcomes (such as patients’ understanding), affective outcomes (such as preference for communication method) and behavioral outcomes (such as treatment choice).

Methods

Search method

A literature search was conducted on the 28th of March 2018 in PubMed, Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and Web of Science. A search update was performed on the 14th of November 2019. Scanning the references of the articles that were initially retained, using citation analysis, helped us to create a set of potentially relevant publications. From this reference set, key concepts for the systematic search were identified. All references from this search had to be retrieved by the final systematic search. Keywords related to the concepts of (surrogate) patients, communication methods (such as graphical, numerical and verbal information), outcomes (such as preference and understanding) and study designs (such as randomized controlled trial and observational studies) were used to search the databases. A broad search strategy was applied (see Online Resource 1). Duplicates were removed and articles were screened on eligibility based on title and abstract using Rayyan [11] by six reviewers independently. Each article was screened in duplicate by two reviewers. The search in March 2018 was screened by three reviewer pairs (JJvK and LvdW, JJvK and IH, NVM and KS) and the search update in November 2019 was screened by LvdW and WD. The same reviewer pairs were used for title and abstract screening and for screening of the full-text articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All studies published in English up to November 14, 2019 with the following characteristics were included:

Population and context

Studies in which the participants (≥ 18 years) were diagnosed with cancer were included, as were studies that involved healthy surrogate cancer patients (≥ 18 years), i.e., healthy participants answering as if they had cancer. Only studies focusing on risk communication regarding treatment decisions were included; studies on risk communication in cancer screening programs were excluded.

Study design

Randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials and cross-sectional and longitudinal observational studies were included. Qualitative/mixed method studies were only included if (1) quantitative data could be extracted in relation to an outcome and (2) a risk communication intervention was offered. Between- and within-subjects studies were included. Case–control and case-series studies were excluded, as were reports, book chapters, conference abstracts and theses.

Interventions

Any method of communicating probabilistic information was included. If different communication methods were compared, the same data needed to have been presented in the compared formats. When studies used decision aids as part of an intervention, the (manipulated) characteristics of the risk communication format needed to have been described in a detailed manner.

Outcomes

Cognitive outcomes (e.g., patients’ understanding), affective outcomes (e.g., patients’ preference for the format) and behavioral outcomes (e.g., patients’ treatment choice) were included.

Data extraction

Data regarding study characteristics and outcomes were extracted by LvdW, using an extraction sheet. Outcomes were classified according to Zipkin et al. using the categories of cognitive, affective and behavioral outcomes [8].

Quality assessment

For the randomized, between-subjects trials, methodological quality was assessed with a combination of the criteria formulated by the adapted Cochrane Collaboration Consumer and Communication review group [12] and items from the Cochrane Collaboration Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias (Online Resource 2). The scale involves nine items, which were rated as either ‘not fulfilled’ (0), ‘fulfilled’ (1) or ‘not specified’ (0). Studies with positive scores on more than half of the items (> 4.5) were considered as ‘high quality’. Cross-sectional studies using a within-subjects comparison on the outcomes of interest were rated with an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for Evaluating Cross-sectional/Survey Studies (Online Resource 3). This scale involves nine items, scored with a maximum of two points per item. Studies with scores > 75% of total attainable points were considered ‘high quality’, scores > 50% as ‘moderate quality’ and 50% or less as ‘low quality’ [13]. For qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist [14] was used to assess methodological quality, which consists of ten items scored with a maximum of 20 points in total [15]. The same cut-off scores as for cross-sectional studies were applied [13]. Quality assessment was performed by LvdW who, in case of uncertainty, discussed with a second reviewer (JJvK) until agreement was reached. To ensure a comprehensive review of the literature, assessed methodological quality was not set as an exclusion criterion.

Data analysis

Studies were subdivided according to the type of type of prognostic information: disease progression, side effects and complications or HRQL. Information on disease progression includes information about survival, progression, remission and recurrence. Verbal and visual communication methods were defined, as shown in Table 1. Analysis was performed separately per type of prognostic information. For each information type, studies investigating the same communication methods were compared according to outcomes (cognitive, affective and behavioral).

Results

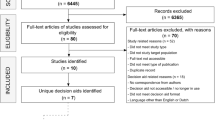

The search in PubMed, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Embase and Web of Science yielded 20,102 articles; removing duplicates resulted in a total of 14,875 articles for screening. Of these, 181 were screened full text, and 28 were included. A summary of the search results can be found in Fig. 1.

Cognitive outcomes were categorized into interpretation accuracy, subjective understanding (including confusion) and cognitive effort. Affective outcomes were categorized into preference for format, satisfaction with format and perceived usefulness (including helpfulness for decision making). All behavioral outcomes (including endorsement of treatment and treatment preference or intentions) were categorized as treatment choice. We found that this outcome was only assessed in studies with disease progression or side effects and complications information.

Seventeen studies investigated probabilistic information regarding disease progression, of which eleven studies included cognitive outcomes (interpretation accuracy, subjective understanding and cognitive effort) [5, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], ten studies included affective outcomes (preference and perceived usefulness) [5, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24,25,26,27,28] and seven studies included behavioral outcomes (treatment choice) [17, 21, 23, 24, 29,30,31]. One study was not included in the behavioral outcome analysis, because it lacked a control group [26]. Of the seventeen studies on disease progression information, fourteen studies investigated information on survival, two studies on recurrence, one study on progression and one study on remission.

Seven studies investigated probabilistic information regarding side effects or complications, of which four studies included cognitive outcomes (interpretation accuracy) [28, 32,33,34], six studies included affective outcomes (preference and satisfaction) [28, 32,33,34,35,36] and one study included the behavioral outcome treatment choice [37].

Five studies investigated probabilistic information regarding HRQL, of which four studies included cognitive outcomes (interpretation accuracy and subjective understanding) [38,39,40,41] and four studies included affective outcomes (preference and perceived usefulness) [38, 39, 41, 42].

Eleven studies included (cancer) patients [5, 18,19,20,21,22, 26, 28, 36, 38, 42], eight studies included healthy volunteers [16, 17, 23,24,25, 27, 31, 37] and nine studies included both cancer patients and either healthy volunteers or health-care professionals or all of these [29, 30, 32,33,34,35, 39,40,41].

Methodological quality

For randomized, between-subjects studies, methodological quality was rated high for seven studies [16, 23, 25, 32, 34, 35, 37] and low for seven studies [17, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 40]. Specific scores can be found in Online Resource 4. Items that were often not sufficiently described encompassed whether the method of randomization was truly random, whether allocation was concealed, whether the data analyst was blinded and whether all prespecified outcomes were reported. Only four out of fourteen studies used validated outcome measures to assess one of the outcomes.

For nonrandomized within-subjects cross-sectional studies, methodological quality was rated high for none of the studies, moderate for nine studies [19, 20, 22, 26, 36, 38, 39, 41, 42] and low for four studies [5, 28, 29, 31]. Statistical testing and nonresponse were often reported in insufficient detail. The representativeness and size of the sample were often not satisfactory. All studies used self-report measures, and only two out of eleven studies used validated measures to assess one of the outcomes.

Methodological quality was moderate for the one qualitative study that was included [18].

Because each study assessed and compared another set of communication methods, effects were only described in text if communication methods were compared in more than one study. An overview of the studies’ compared methods and results can be found in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Probabilistic information on disease progression

Table 2 provides a summary of the results regarding the communication of information about disease progression. Eleven of these studies investigated the effect of different formats on cognitive outcomes. Based on three studies, of which two were of high methodological quality and one of low, graphs were better understood (interpretation accuracy and cognitive effort) when there was less information for the participant to process at one time (in one graph or in different graphs presented at once), compared to more information [23,24,25]. One study of low quality supported this conclusion for verbal formats, by showing higher confusion rates when different formats were presented all at once, compared to separate presentation [17]. Contradictory results were found when verbal information was compared to graphical information; two studies found higher subjective understanding for words compared to graphs (moderate quality) [20] or compared to graphs accompanied by words (low quality) [21]. However, one study of moderate quality found that graphs were objectively better understood than words [19]. No further conclusions could be drawn on cognitive outcomes because of heterogeneity in the compared communication formats.

Ten studies included affective outcomes, of which nine investigated a preference for formats and two investigated the perceived usefulness of the formats. Although there was much variation in compared formats, two studies, both of high methodological quality, did compare pictographs (among other formats) with bar charts [16, 25]. However, these two studies found conflicting results: one found bar charts to be preferred over pictographs [16] and the other found pictographs to be preferred over bar charts [25]. Two studies of low and moderate quality found positive framing to be preferred over negative framing, although none performed statistical analysis on this effect [5, 18]. When comparing words to numbers, three studies, of low and moderate quality, found conflicting results, of which none performed statistical analysis on this comparison [5, 26, 28].

Seven studies investigated the behavioral outcome treatment choice. Different treatment options were presented in these studies, ranging from very specific (radiotherapy) to more general descriptions of treatment (an unknown treatment that is more toxic but also has higher survival rates). In all but one study there were only two possible options [23]. Three studies investigated the differences in treatment choice when information was framed positively (in terms of survival), negatively (in terms of death) or both (mixed frame) [29,30,31]. Two of these, both of low methodological quality, found that surgery (higher chance of survival, but risk of perioperative death) was more frequently chosen (instead of radiotherapy—lower chance of survival and more side effects) when information was framed positively instead of negatively [29, 31]. When patients in another low-quality study had to choose between a treatment that was more effective, but more toxic, and one that was less effective and less toxic, the first was less preferred in a negative frame (compared to positive and mixed) [30].

Probabilistic information on side effects and complications

Table 3 provides a summary of the results regarding information about side effects and complications. Seven studies investigated the effects of communication methods on side effects and complications information [28, 32,33,34,35,36,37], of which four investigated the cognitive outcome interpretation accuracy, six the affective outcomes preference or satisfaction and one the behavioral outcome treatment choice. Two studies of high methodological quality compared accuracies for risk information in words to percentages and/or frequencies. These studies found that more precise risk information about side effects (percentage/frequency) was superior to information in words [32, 34]. When comparing frequencies to percentages, no clear effect was found. One study of low quality only found a difference on one of six check questions, showing higher accuracies for percentages [33].

Concerning satisfaction with and preferences for communication methods, most studies did not find a significant difference between formats. However, one study of high quality found that communicating frequencies instead of (solely) verbal risk information can contribute significantly to patient satisfaction [34]. Two other studies of low and moderate quality found a description in both words and numbers and a (detailed) description in words only to be most preferred [28, 36]. These two studies did however not report statistical analysis on these preferences.

Probabilistic information on health-related quality of life

Table 4 provides a summary of the results regarding HRQL information. Four studies compared different methods of communicating HRQL information on cognitive outcomes three looked at interpretation accuracy and four looked at subjective understanding. One study of moderate methodological quality found that basic line graphs were best understood (objectively and subjectively; compared to textual descriptions, line graphs with ranges and several different bar chart formats) [38]. Another moderate-quality study found simple line graphs to score highest on ease of understanding, but did not report any statistical testing on this outcome [39]. With respect to the directionality of line graphs, a study of low quality found lines going up meaning better outcomes, to be interpreted more accurately than lines going up meaning more of the outcome or normed lines [40]. A third study of moderate quality, however, found pie charts to be best understood (objectively and subjectively, compared to bar charts and icon arrays), but did not report statistical testing on this outcome for patients separately [41].

Affective outcomes for HRQL data were compared in four studies. Three studies measured perceived usefulness and one study measured preference for communication method. Three studies found that simple line graphs displaying mean scores were perceived as most useful [38, 39, 42], of which only one study, of moderate quality, reported a significant difference between formats: line graphs displaying mean scores were perceived as most helpful (compared to line graphs with ranges, textual descriptions and various bar chart formats) [38]. Another study, however, reported pie charts to be most positively commented on, compared to bar charts and icon arrays [41].

Discussion

In this review, we summarized the literature on methods of communicating probabilistic information in oncological treatment decision-making processes.

For communication of disease progression information, we found that the type of framing has an influence on treatment choice. This has also been observed in communication in general health care [8]; positive framing (in terms of survival instead of mortality) may increase acceptance of treatments. However, in this review, we could not draw any conclusions regarding the direction of the effect due to the incomparability of treatment choices and to the low methodological quality of the studies.

Furthermore, we found that limiting the amount of survival information that the patient has to process at once in a graphical display could benefit the patients’ understanding. There is growing evidence supporting the so-called ‘less is more’ approach in the field of decision-making; simpler forms of communication can make it easier for patients to use the information during decision making [24]. Additionally, it has been argued that the complexity of information may contribute to patients’ experience of uncertainty [43].

We found that precise and defined risk information (e.g., percentages) about side effects was better understood than verbal information. Here, however, a potential source of bias could exist in the way that outcomes were measured. To prevent recall bias, the risk format used in the outcome assessment should not be similar to the format used as an intervention. For example, comparing percentages to another format would not be completely ‘fair’ when the answer to an accuracy question has to be stated in percentages, as is the case in at least two of three accuracy studies. However, finding a suitable assessment format that will not be influenced by recall might be challenging in these cases.

For display of HRQL information, we did not find consensus among the included studies on which type of graphs to use. Whereas line graphs and pie charts seemed to result in better cognitive and affective outcomes, these results were only based on one significant result each. While a previous review in general health care [8] recommends using icon arrays or bar charts to display outcome information, recent studies on the display of HRQL information specifically, suggested using pie charts [44, 45]. Another issue is the direction of display of HRQL data when using bar or line graphs. Where other literature in HRQL research—beyond the scope of this review—recommends the graphical display direction of better = higher [45, 46], we did not find enough evidence—one study—to recommend on the direction of HRQL graphs [40].

Great heterogeneity was found not only in the study results but also in methodology and in the compared communication formats. This precludes us from stating separate practice recommendations for the three different types of risk information (disease progression, side effects and complications and HRQL). Most importantly, several studies investigated the same communication methods and found different effects on outcomes. Therefore, a meta-analysis would be of great help. However, for meta-analysis to be possible, the heterogeneity in methodology and compared risk formats needs to be less substantial.

Furthermore, the overall methodological quality of most studies was found to be moderate, which was largely due to the lack of details to properly assess the risk of bias. Additionally, validated measures were not frequently used to assess the analyzed outcomes. The latter may be because few validated measures exist that are applicable to multiple risk information situations. Notably, the adapted quality grading criteria may not have been perfectly suited to evaluate the studies as designed and was only performed by a single author, except where that author requested input from a second author.

In addition to the moderate overall quality and the heterogeneity of studies, the following aspects may also have influenced the outcomes of this review. First, we included studies in which participants were not always cancer patients themselves, but for example students, patients in an outpatient clinic or website visitors. The hypothetical scenario presented to participants could have been less relevant to this group in comparison to patients. Furthermore, by including students, there is a potential effect of numeracy and graph literacy levels, possibly resulting in higher understanding among these participants. We therefore suggest that numeracy and graph literacy be assessed in future research on the subject. We also suggest that social and cultural background variables be assessed in future research, to be able to describe their influence on risk communication.

Despite the above, when combining the results on all three information types, we can provide two main suggestions for cancer clinical practice. First, we recommend that clinicians treating cancer patients consider the effects that positive and negative framing might have on the treatment choice of the patient. Second, we suggest that clinicians not only use words when describing risks but at least also use some form of numbers or visualization to discuss risk. Future researchers should take numeracy and graph literacy effects into account, carefully choose their measures and describe the procedures used in more detail.

References

Stiggelbout, A. M., Pieterse, A. H., & De Haes, J. (2015). Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Education and Counseling,98(10), 1172–1179.

Stiggelbout, A. M., Van der Weijden, T., De Wit, M. P., Frosch, D., Légaré, F., Montori, V. M., et al. (2012). Shared decision making: Really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ,344, e256.

Elwyn, G., Laitner, S., Coulter, A., Walker, E., Watson, P., & Thomson, R. J. B. (2010). Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ,341, c5146.

Sepucha, K. R., Fowler, F. J., Jr., & Mulley, A. G., Jr. (2004). Policy support for patient-centered care: The need for measurable improvements in decision quality: Documenting gaps in patients' knowledge could stimulate rapid change, moving decisions and care closer to a patient-centered ideal. Health Affairs,23(Suppl2), 62.

Lobb, E. A., Butow, P. N., Kenny, D. T., & Tattersall, M. H. (1999). Communicating prognosis in early breast cancer: Do women understand the language used? Medical Journal of Australia,171(6), 290–294.

Engelhardt, E. G., Pieterse, A. H., van der Hout, A., de Haes, H. J., Kroep, J. R., van Ufford-Mannesse, P. Q., et al. (2016). Use of implicit persuasion in decision making about adjuvant cancer treatment: A potential barrier to shared decision making. European Journal of Cancer,66, 55–66.

Kunneman, M., Stiggelbout, A. M., Marijnen, C. A., & Pieterse, A. H. (2015). Probabilities of benefit and harms of preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: What do radiation oncologists tell and what do patients understand? Patient Education and Counseling,98(9), 1092–1098.

Zipkin, D. A., Umscheid, C. A., Keating, N. L., Allen, E., Aung, K., Beyth, R., et al. (2014). Evidence-based risk communication: A systematic review evidence-based risk communication. Annals of Internal Medicine,161(4), 270–280.

Liénard, A., Merckaert, I., Libert, Y., Delvaux, N., Marchal, S., Boniver, J., et al. (2006). Factors that influence cancer patients' anxiety following a medical consultation: Impact of a communication skills training programme for physicians. Annals of Oncology,17(9), 1450–1458.

Visser, L. N., Tollenaar, M. S., Bosch, J. A., van Doornen, L. J., de Haes, H. C., & Smets, E. M. (2017). Are psychophysiological arousal and self-reported emotional stress during an oncological consultation related to memory of medical information? An experimental study. Stress,20(1), 103–111.

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews,5(1), 210.

Henselmans, I., de Haes, H. C., & Smets, E. M. (2013). Enhancing patient participation in oncology consultations: A best evidence synthesis of patient-targeted interventions. Psycho-Oncology,22(5), 961–977.

Hillen, M. A., Medendorp, N. M., Daams, J. G., & Smets, E. M. (2017). Patient-driven second opinions in oncology: A systematic review. The Oncologist,22(10), 1197–1211.

UK, C. (2018). CASP Checklists. Retrieved October 5, 2019, from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

Currie, K., Melone, L., Stewart, S., King, C., Holopainen, A., Clark, A. M., et al. (2018). Understanding the patient experience of health care–associated infection: A qualitative systematic review. American Journal of Infection Control,46(8), 936–942.

Hamstra, D. A., Johnson, S. B., Daignault, S., Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., Taylor, J. M., Larkin, K., et al. (2015). The impact of numeracy on verbatim knowledge of the longitudinal risk for prostate cancer recurrence following radiation therapy. Medical Decision Making,35(1), 27–36.

Chao, C., Studts, J. L., Abell, T., Hadley, T., Roetzer, L., Dineen, S., et al. (2003). Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: How presentation of recurrence risk influences decision-making. Journal of Clinical Oncology,21(23), 4299–4305.

Davey, H., Butow, P., & Armstrong, B. (2003). Cancer patients' preferences for written prognostic information provided outside the clinical context. British Journal of Cancer,89(8), 1450–1456.

Davis, C., McNair, A., Brigic, A., Clarke, M., Brookes, S., Thomas, M., et al. (2010). Optimising methods for communicating survival data to patients undergoing cancer surgery. European Journal of Cancer,46(18), 3192–3199.

Hagerty, R., Butow, P., Ellis, P., Lobb, E., Pendlebury, S., Leighl, N., et al. (2004). Cancer patient preferences for communication of prognosis in the metastatic setting. Journal of Clinical Oncology,22(9), 1721–1730.

Kang, S. K., Scherer, L. D., Megibow, A. J., Higuita, L. J., Kim, N., Braithwaite, R. S., et al. (2018). A randomized study of patient risk perception for incidental renal findings on diagnostic imaging tests. American Journal of Roentgenology,210(2), 369–375.

Kiely, B. E., Mccaughan, G., Christodoulou, S., Beale, P. J., Grimison, P., Trotman, J., et al. (2013). Using scenarios to explain life expectancy in advanced cancer: attitudes of people with a cancer experience. Supportive Care in Cancer,21(2), 369–376.

Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., Angott, A. M., & Ubel, P. A. (2011). The benefits of discussing adjuvant therapies one at a time instead of all at once. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment,129(1), 79–87.

Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., Fagerlin, A., & Ubel, P. A. (2010). A demonstration of ‘‘less can be more’’ in risk graphics. Medical Decision Making,30(6), 661–671.

Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., Fagerlin, A., & Ubel, P. A. (2008). Improving understanding of adjuvant therapy options by using simpler risk graphics. Cancer,113(12), 3382–3390.

Mazur, D. J., Hickam, D. H., & Mazur, M. D. (1999). How patients' preferences for risk information influence treatment choice in a case of high risk and high therapeutic uncertainty: Asymptomatic localized prostate cancer. Medical Decision Making,19(4), 394–398.

Studts, J. L., Abell, T. D., Roetzer, L. M., Albers, A. N., McMasters, K. M., & Chao, C. (2005). Preferences for different methods of communicating information regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology,14(8), 647–660.

Carey, M., Herrmann, A., Hall, A., Mansfield, E., & Fakes, K. (2018). Exploring health literacy and preferences for risk communication among medical oncology patients. PLoS ONE,13(9), e0203988.

McNeil, B. J., Pauker, S. G., Sox Jr, H. C., & Tversky, A. (1982). 23 on the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies. Preference, Belief, Similarity, 583

O'Connor, A. M. (1989). Effects of framing and level of probability on patients' preferences for cancer chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,42(2), 119–126.

Woodhead, E. L., Lynch, E. B., & Edelstein, B. A. (2011). Decisional strategy determines whether frame influences treatment preferences for medical decisions. Psychology and Aging,26(2), 285.

Knapp, P., Gardner, P., Carrigan, N., Raynor, D., & Woolf, E. (2009). Perceived risk of medicine side effects in users of a patient information website: A study of the use of verbal descriptors, percentages and natural frequencies. British Journal of Health Psychology,14(3), 579–594.

Knapp, P., Gardner, P., McMillan, B., Raynor, D. K., & Woolf, E. (2013). Evaluating a combined (frequency and percentage) risk expression to communicate information on medicine side effects to patients. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice,21(4), 226–232.

Knapp, P., Raynor, D. K., Woolf, E., Gardner, P. H., Carrigan, N., & McMillan, B. (2009). Communicating the risk of side effects to patients. Drug Safety,32(10), 837–849.

Knapp, P., Gardner, P. H., & Woolf, E. (2016). Combined verbal and numerical expressions increase perceived risk of medicine side-effects: A randomized controlled trial of EMA recommendations. Health Expectations,19(2), 264–274.

Zomorodbakhsch, B., Keinki, C., Seilacher, E., & Huebner, J. (2018). Cancer patients numeracy and preferences for information presentation—A survey among German cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Education,35, 22–27.

Gurich, R. W., Jr., Cizik, A. M., Punt, S. E., Namekata, M., Johnson, C. N., Symons, R. G., et al. (2019). Decision-making in orthopaedic oncology: Does cognitive bias affect a virtual patient’s choice between limb salvage and amputation? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®,478, 506–514.

Brundage, M., Feldman-Stewart, D., Leis, A., Bezjak, A., Degner, L., Velji, K., et al. (2005). Communicating quality of life information to cancer patients: A study of six presentation formats. Journal of Clinical Oncology,23(28), 6949–6956.

Brundage, M. D., Smith, K. C., Little, E. A., Bantug, E. T., & Snyder, C. F. (2015). Communicating patient-reported outcome scores using graphic formats: Results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Quality of Life Research,24(10), 2457–2472.

Tolbert, E., Brundage, M., Bantug, E., Blackford, A. L., Smith, K., Snyder, C., et al. (2018). Picture this: Presenting longitudinal patient-reported outcome research study results to patients. Medical Decision Making,38(8), 994–1005.

Tolbert, E., Brundage, M., Bantug, E., Blackford, A. L., Smith, K., Snyder, C., et al. (2019). In proportion: Approaches for displaying patient-reported outcome research study results as percentages responding to treatment. Quality of Life Research,28(3), 609–620.

Brundage, M., Leis, A., Bezjak, A., Feldman-Stewart, D., Degner, L., Velji, K., et al. (2003). Cancer patients' preferences for communicating clinical trial quality of life information: A qualitative study. Quality of Life Research,12(4), 395–404.

Han, P. K., Klein, W. M., & Arora, N. K. (2011). Varieties of uncertainty in health care: A conceptual taxonomy. Medical Decision Making,31(6), 828–838.

Snyder, C., Smith, K., Holzner, B., Rivera, Y. M., Bantug, E., Brundage, M., et al. (2019). Making a picture worth a thousand numbers: Recommendations for graphically displaying patient-reported outcomes data. Quality of Life Research,28(2), 345–356.

Brundage, M., Blackford, A., Tolbert, E., Smith, K., Bantug, E., Snyder, C., et al. (2018). Presenting comparative study PRO results to clinicians and researchers: Beyond the eye of the beholder. Quality of Life Research,27(1), 75–90.

Snyder, C. F., Smith, K. C., Bantug, E. T., Tolbert, E. E., Blackford, A. L., Brundage, M. D., et al. (2017). What do these scores mean? Presenting patient-reported outcomes data to patients and clinicians to improve interpretability. Cancer,123(10), 1848–1859.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing and publishing the report.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (DCS) under Grant Number UVA 2014-7000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: HWMvL, JJvK; Methodology: LFvdW, JJvK; Formal analysis and investigation: LFvdW, JJvK, WPMD, IH, NMVM, KFS; Writing—original draft preparation: LFvdW; Writing—review and editing: LFvdW, JJvK, IH, HGvdB, NMVM, KFS, JGD, EMAS, HWMvL; Funding acquisition: HWMvL; Supervision: HWMvL, EMAS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests

Prof. dr. van Laarhoven reports grants from the Dutch Cancer Society, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from BMS, Lilly, and Nordic Pharma; and grants and nonfinancial support from Bayer, BMS, Celgene, Jansen, Lilly, Nordic Pharma, Philips, Roche and Servier outside of this work. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van de Water, L.F., van Kleef, J.J., Dijksterhuis, W.P.M. et al. Communicating treatment risks and benefits to cancer patients: a systematic review of communication methods. Qual Life Res 29, 1747–1766 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02503-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02503-8