Abstract

Background

Recent work on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) focuses on precise, brief measures, which generally convey little about what an individual’s rating actually means. Individual differences in appraisal are important and relevant to PRO research. This paper highlights the advantages of integrating appraisal assessment into clinical research.

Methods

The most comprehensive method for assessing appraisal, the quality of life (QOL) Appraisal Profile, includes open-ended and multiple choice questions to assess four appraisal parameters: frame of reference, sampling of experience, standards of comparison, and combinatory algorithm. We illustrate with empirical findings four classes of investigation that would benefit from appraisal assessment: methodological, interpretation of change, the backstory of resilience, and clinical applications.

Results

A methodological investigation of HIV/AIDS patients revealed a range of cognitive schemas induced by the then-test response shift detection method, only 15% of which reflected the presumed process invoked. In this same study and in a study of people with multiple sclerosis (MS), interpretation of change in positive versus negative mental-health response shifts was characterized by different appraisal processes. In studying resilience in MS patients, patients with more reserve-building activities were more likely to use appraisals that emphasized the positive and more controllable aspects of their illness experience, as compared to lower-reserve patients. In underserved cancer patients, the QOL Appraisal Profile was used as a clinical interview to articulate current concerns and for personalized treatment decision-making to reduce burden and promote adherence.

Conclusions

Integrating appraisal assessment can provide a more textured, person-centered understanding of person-factors not captured by standard PROs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

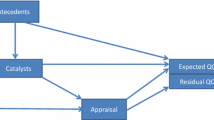

Rapkin, B. D., & Schwartz, C. E. (2004). Toward a theoretical model of quality-of-life appraisal: Implications of findings from studies of response shift. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2(1), 14.

Schwartz, C. E., & Rapkin, B. D. (2004). Reconsidering the psychometrics of quality of life assessment in light of response shift and appraisal. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 16.

Sprangers, M. A., & Schwartz, C. E. (1999). Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Social Science and Medicine, 48(11), 1507–1515.

Schwartz, C. E., & Sprangers, M. A. (1999). Methodological approaches for assessing response shift in longitudinal health-related quality-of-life research. Social Science and Medicine, 48(11), 1531–1548.

Schwartz, C. E., et al. (2011). Response shift in patients with multiple sclerosis: An application of three statistical techniques. Quality of Life Research, 20(10), 1561–1572.

Oort, F. J. (2005). Using structural equation modeling to detect response shifts and true change. Quality of Life Research, 14, 587–598.

Mayo, N., Scott, C., & Ahmed, S. (2009). Case management post-stroke did not induce response shift: The value of residuals. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1148–1156.

Boucekine, M., et al. (2013). Using the random forest method to detect a response shift in the quality of life of multiple sclerosis patients: A cohort study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 20.

Lix, L. M., et al. (2013). Relative importance measures for reprioritization response shift. Quality of Life Research, 22(4), 695–703.

Li, Y., & Rapkin, B. (2009). Classification and regression tree analysis to identify complex cognitive paths underlying quality of life response shifts: A study of individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1138–1147.

Ring, L., et al. (2005). Response shift masks the treatment impact on patient reported outcomes: The example of individual quality of life in edentulous patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 3, 55.

Ruta, D. A., et al. (1994). A new approach to the measurement of quality of life. The Patient-Generated Index. Med Care, 32(11), 1109–1126.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ross, M. (1989). Relation of implicit theories to the construction of personal histories. Psychological Review, 96(2), 341–357.

Bloem, E. F., et al. (2008). Clarifying quality of life assessment: Do theoretical models capture the underlying cognitive processes? Quality of Life Research, 17, 1093–1102.

Rapkin, B. D., & Fischer, K. (1992). Framing the construct of life satisfaction in terms of older adults’ personal goals. Psychology and Aging, 7(1), 138–149.

Rapkin, B. D., & Fischer, K. (1992). Personal goals of older adults: Issues in assessment and prediction. Psychology and Aging, 7(1), 127–137.

Schwartz, C. E., & Rapkin, B. D. (2012). Understanding appraisal processes underlying the then-test: A mixed methods investigation. Quality of Life Research, 21(3), 381–388.

Rapkin, B. D., et al. (1994). Development of the idiographic functional status assessment: A measure of the personal goals and goal attainment activities of people with AIDS. Psychology and Health, 9, 111–129.

Schwartz, C. E., et al. (2013). Cognitive reserve and appraisal in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 2(1), 36–44.

Rapkin, B. D., et al. (2011). User manual for the quality of life Appraisal Profile. Concord, MA: DeltaQuest Foundation, Inc.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357.

Morganstern, B. A., et al. (2011). The psychological context of quality of life: A psychometric analysis of a novel idiographic measure of bladder cancer patients’ personal goals and concerns prior to surgery. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1):1.

Norman, G. (2003). Hi! How are you? Response shift, implicit theories and differing epistemologies. Quality of Life Research, 12(3), 239–249.

Miller, R. G., Jr. (1977). Developments in multiple comparisons 1966–1976. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 72(360a), 779–788.

Howard, G. S., Dailey, P. R., & Gulanick, N. A. (1979). The feasibility of informed pre-tests in attenuating response-shift bias. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 481–494.

Sprangers, M. A., et al. (1999). Revealing response shift in longitudinal research on fatigue—the use of the thentest approach. Acta Oncologica, 38(6), 709–718.

Schwartz, C. E., & Sprangers, M. A. G. (2010). Guidelines for improving the stringency of response shift research using the then-test. Quality of Life Research, 19, 455–464.

Schwartz, C. E., et al. (2004). Exploring response shift in longitudinal data. Psychology and Health, 19(1), 51–69.

Ahmed, S., et al. (2005). Change in quality of life in people with stroke over time: True change or response shift? Quality of Life Research, 14, 611–627.

McPhail, S., & Haines, T. (2010). Response shift, recall bias and their effect on measuring change in health-related quality of life amongst older hospital patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 1.

Schwartz, C. E., et al. (2006). The clinical significance of adaptation to changing health: A meta-analysis of response shift. Quality of Life Research, 15, 1533–1550.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239.

Schwartz, C. E., et al. (2014). Fluctuations in appraisal over time in the context of stable and non-stable health. Quality of Life Research, 23(1), 9–19.

Reeve, B. B., et al. (2013). ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Quality of Life Research, 22(8), 1889–1905.

Jaeschke, R., Singer, J., & Guyatt, G. H. (1989). Measurement of health status: Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Controlled Clinical Trials, 10(4), 407–415.

Kamper, S. J., Maher, C. G., & Mackay, G. (2009). Global rating of change scales: A review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, 17(3), 163–170.

Beaton, D. E. (2000). Understanding the relevance of measured change through studies of responsiveness. Spine, 25(24), 3192–3199.

Beaton, D. E., et al. (2001). A taxonomy for responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(12), 1204–1217.

Cella, D., Hahn, E. A., & Dineen, K. (2002). Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: Differences between improvement and worsening. Quality of Life Research, 11(3), 207–221.

Schwartz, C. E., et al. (2012). The Symptom Inventory disability-specific short-forms for multiple sclerosis: Construct validity, responsiveness, and interpretation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(9), 1617–1628.

Kvam, A. K., Wisloff, F., & Fayers, P. M. (2010). Minimal important differences and response shift in health-related quality of life; A longitudinal study in patients with multiple myeloma. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 79.

Fitzpatrick, R., et al. (1993). Transition questions to assess outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology, 32(9), 807–811.

Kamper, S. J., et al. (2010). Global perceived effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(7), 760–766.

Schwartz, C. E., Powell, V. E., & Rapkin, B. D. (2016). When global rating of change contradicts observed change: Examining appraisal processes underlying paradoxical responses over time. Quality of Life Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1414-3.

Taminiau-Bloem, E. F., et al. (2010). A ‘short walk’ is longer before radiotherapy than afterwards: A qualitative study questioning the baseline and follow-up design. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 1.

Neudert, C., Wasner, M., & Borasio, G. D. (2004). Individual quality of life is not correlated with health-related quality of life or physical function in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 7(4), 551–557.

Astin, J. A., et al. (1999). Sense of control and adjustment to breast cancer: The importance of balancing control coping styles. Behavioral Medicine, 25(3), 101–109.

Shapiro, D. H., Jr., Schwartz, C. E., & Astin, J. A. (1996). Controlling ourselves, controlling our world. Psychology’s role in understanding positive and negative consequences of seeking and gaining control. American Psychologist, 51(12), 1213–1230.

Linville, P. W. (1987). Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 663–676.

Nevadunsky, N. S., et al. (2014). The role and timing of palliative medicine consultation for women with gynecologic malignancies: Association with end of life interventions and direct hospital costs. Gynecologic Oncology, 132(1), 3–7.

Nevadunsky, N. S., et al. (2011). Utilization of palliative medicine in a racially and ethnically diverse population of women with gynecologic malignancies. Cancer Research, 71(8 Suppl), 5026.

Kim, A., Fall, P., & Wang, D. (2005). Palliative care: Optimizing quality of life. Journal-American Osteopathic Association, 105(11), S9.

Lorenz, K. A., et al. (2008). Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148(2), 147–159.

Bakitas, M., et al. (2009). Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 302(7), 741–749.

Temel, J. S., et al. (2011). Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(17), 2319–2326.

Temel, J. S., et al. (2010). Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(8), 733–742.

Ohri, N., et al. (2015). Predictors of radiation therapy noncompliance in an urban academic cancer center. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 91(1), 232–238.

McDonald, H. P., Garg, A. X., & Haynes, R. B. (2002). Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: Scientific review. JAMA, 288(22), 2868–2879.

Rapkin, B., et al. (2016). Assessment of quality of life Appraisal in patient-centered care. In American Psychosocial Oncology Society annual meeting, San Diego, CA.

Schwartz, C. E., Li, J., & Rapkin, B. D. (2016). Refining a web-based goal assessment interview: Item reduction based on reliability and predictive validity. Quality of Life Research, 10, 1–12.

Botteman, M., et al. (2003). Quality of life aspects of bladder cancer: A review of the literature. Quality of Life Research, 12(6), 675–688.

Sandler, J. (2007). Community-based practices: Integrating dissemination theory with critical theories of power and justice. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40(3–4), 272–289.

Diemer, M. A., et al. (2015). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of critical consciousness. The Urban Review, 47(5), 809–823.

Choy, Y., Fyer, A. J., & Lipsitz, J. D. (2015). Cognitive restructuring (p. 88). Phobias: The Psychology of Irrational Fear.

Nowlan, J. S., et al. (2015). A comparison of single-session positive reappraisal, cognitive restructuring and supportive counselling for older adults with type 2 diabetes. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(2):216–229.

Prilleltensky, I. (2008). The role of power in wellness, oppression, and liberation: The promise of psychopolitical validity. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(2), 116–136.

Fetterman, D. M., & Wandersman, A. (2005). Empowerment evaluation principles in practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Cyril, S., Smith, B. J., & Renzaho, A. M. (2015). Systematic review of empowerment measures in health promotion. Health Promotion International. doi:10.1093/heapro/dav059.

Finkelstein, J., et al. (2012). Appraisal processes in people awaiting spine surgery: Investigating quality of life using mixed methods [Abstract]. Quality of Life Research, 20, 106.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by a Grant from the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI #ME-1306-00781) to Dr. Rapkin. We are grateful to Yuelin Li, Ph.D., for helpful discussions over time that have led to novel analytic uses of the QOL Appraisal Profile data as well as conceptualizations related to the psychology of memory; to Nicole Nevadunsky, MD, and Madhur Garg, MD, for helpful discussions related to clinical applications of the QOL Appraisal Profile; and to anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Rapkin declares that he is the author of the QOL Appraisal Profile, but has no conflict of interest. Drs. Schwartz and Finkelstein declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and animal rights statement

All work mentioned is published work, not a new study involving human or animal subjects.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, C.E., Finkelstein, J.A. & Rapkin, B.D. Appraisal assessment in patient-reported outcome research: methods for uncovering the personal context and meaning of quality of life. Qual Life Res 26, 545–554 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1476-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1476-2