Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study is to estimate the EQ-5D-derived health utilities associated with selected chronic conditions (hypertension, heart disease, arthritis, asthma or COPD, cancer, diabetes, chronic back pain, and anxiety or depression) and to estimate minimally important differences (MID) based on the Commonwealth Fund Survey of Sicker Adults in Canada.

Methods

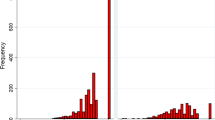

We used a cross-sectional survey of 3765 sick adults in Canada conducted in 2011 by the Commonwealth Fund. Health utilities were calculated for the entire sample and for each of the eight chronic health conditions. An ordinary least squares regression was used to estimate the utility decrement associated with these conditions with and without adjustment for socio-demographic factors. The MIDs were estimated using the anchor- and distribution-based methods.

Results

The adjusted utility decrement varied from 0.028 (95 % confidence interval (CI) −0.049, −0.008) for diabetes to 0.124 (95 % CI −0.142, −0.105) for anxiety or depression. The anchor-based MID for the entire group was 0.044 (95 % CI 0.025, 0.062), and the distribution-based MID for the entire group was 0.091. The condition-specific MIDs using the distribution-based method ranged from 0.089 for cancer to 0.108 for asthma or COPD.

Conclusions

The MID estimated by the distribution-based method was larger than the MID estimated by the anchor-based method, indicating that the choice of method matters. The impact of arthritis, anxiety or depression, and chronic back pain on health utility was substantial, all exceeding or approximating the MID estimated using either anchor- or distribution-based methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Guyatt, G. H., Feeny, D. H., & Patrick, D. L. (1993). Measuring health-related quality of life. Annals of Internal Medicine, 118(8), 622–629. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009.

Brożek, J. L., Guyatt, G. H., & Schünemann, H. J. (2006). How a well-grounded minimal important difference can enhance transparency of labelling claims and improve interpretation of a patient reported outcome measure. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 69. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-69.

Copay, A. G., Subach, B. R., Glassman, S. D., Polly, D. W, Jr., & Schuler, T. C. (2007). Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: A review of concepts and methods. The Spine Journal, 7(5), 541–546. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008.

Jaeschke, R., Singer, J., & Guyatt, G. H. (1989). Measurement of health status: Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Controlled Clinical Trials, 10(4), 407–415. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6.

Juniper, E. F., Guyatt, G. H., Willan, A., & Griffith, L. E. (1994). Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 47(1), 81–87. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(94)90036-1.

Lydick, E., & Epstein, R. S. (1993). Interpretation of quality of life changes. Quality of Life Research, 2(3), 221–226. doi:10.2307/4034505.

Schünemann, H. J., Puhan, M., Goldstein, R., Jaeschke, R., & Guyatt, G. H. (2005). Measurement properties and interpretability of the chronic respiratory disease questionnaire (CRQ). Copd: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2(1), 81–89. doi:10.1081/COPD-200050651.

Crosby, R. D., Kolotkin, R. L., & Williams, G. R. (2003). Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56(5), 395–407. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00044-1.

Revicki, D., Hays, R. D., Cella, D., & Sloan, J. (2008). Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(2), 102–109. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012.

Guyatt, G. H., Osoba, D., Wu, A. W., Wyrwich, K. W., & Norman, G. R. (2002). Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 77(4), 371–383. doi:10.4065/77.4.371.

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A., & Wyrwich, K. W. (2003). Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care, 41(5), 582–592.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wyrwich, K. W., Tierney, W. M., & Wolinsky, F. D. (1999). Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 52(9), 861–873. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00071-2.

Dolan, P. (2011). Thinking about it: Thoughts about health and valuing QALYs. Health Economics, 20(12), 1407–1416. doi:10.1002/hec.1679.

Dolan, P. (1997). Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Medical Care, 35(11), 1095–1108.

Le, Q. A., Doctor, J. N., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2013). Minimal clinically important differences for the EQ-5D and QWB-SA in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Results from a doubly randomized preference trial (DRPT). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11, 59. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-59.

Pickard, A. S., Neary, M. P., & Cella, D. (2007). Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 70. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-5-70.

Sullivan, P. W., Lawrence, W. F., & Ghushchyan, V. (2005). A national catalog of preference-based scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Medical Care, 43(7), 736–749.

Walters, S., & Brazier, J. (2005). Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Quality of Life Research, 14(6), 1523–1532. doi:10.1007/s11136-004-7713-0.

Agborsangaya, C., Lau, D., Lahtinen, M., Cooke, T., & Johnson, J. (2013). Health-related quality of life and healthcare utilization in multimorbidity: Results of a cross-sectional survey. Quality of Life Research, 22(4), 791–799. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0214-7.

Chao, Y. S., Ekwaru, J. P., Ohinmaa, A., Griener, G., & Veugelers, P. J. (2014). Vitamin D and health-related quality of life in a community sample of older Canadians. Quality of Life Research, 23(9), 2569–2575. doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0696-6.

Marra, C. A., Woolcott, J. C., Kopec, J. A., Shojania, K., Offer, R., Brazier, J. E., et al. (2005). A comparison of generic, indirect utility measures (the HUI2, HUI3, SF-6D, and the EQ-5D) and disease-specific instruments (the RAQoL and the HAQ) in rheumatoid arthritis. Social Science and Medicine, 60(7), 1571–1582. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.034.

Oremus, M., Tarride, J.-E., Clayton, N., & Raina, P. (2014). Health utility scores in alzheimer’s disease: Differences based on calculation with American and Canadian preference weights. Value in Health, 17(1), 77–83. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2013.10.009.

Schoen, C., Osborn, R., Squires, D., Doty, M., Pierson, R., & Applebaum, S. (2011). New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Affairs, 30(12), 2437–2448.

Harris Interactive Inc. (2011). International health perspectives 2011 survey of sicker adults, methods report.

Rabin, R., & Charro, F. D. (2001). EQ-SD: A measure of health status from the EuroQol group. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 337–343. doi:10.3109/07853890109002087.

Bansback, N., Tsuchiya, A., Brazier, J., & Anis, A. (2012). Canadian valuation of EQ-5D health states: Preliminary value set and considerations for future valuation studies. PLoS ONE,. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031115.

Pullenayegum, E. M., Tarride, J.-E., Xie, F., Goeree, R., Gerstein, H. C., & O’Reilly, D. (2010). Analysis of health utility data when some subjects attain the upper bound of 1: Are tobit and CLAD models appropriate? Value in Health, 13(4), 487–494. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00695.x.

Lumley, T. (2004). Analysis of complex survey samples. Journal of Statistical Software, 9(1), 19. doi:10.18637/jss.v009.i08.

Schisterman, E. F., Cole, S. R., & Platt, R. W. (2009). Overadjustment Bias and Unnecessary Adjustment in Epidemiologic Studies. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 20(4), 488–495. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1.

R Development Core Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Lumley, T. (2012). Survey: Analysis of complex survey samples. R Package Version 3.28–2.

Dyer, M. T. D., Goldsmith, K. A., Sharples, L. S., & Buxton, M. J. (2010). A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 13. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-8-13.

Janssen, M. F., Lubetkin, E. I., Sekhobo, J. P., & Pickard, A. S. (2011). The use of the EQ-5D preference-based health status measure in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine, 28(4), 395–413. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03136.x.

Pickard, A. S., Wilke, C., Jung, E., Patel, S., Stavem, K., & Lee, T. A. (2008). Use of a preference-based measure of health (EQ-5D) in COPD and asthma. Respiratory Medicine, 102(4), 519–536. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2007.11.016.

Supina, A., Johnson, J., Patten, S., Williams, J. A., & Maxwell, C. (2007). The usefulness of the EQ-5D in differentiating among persons with major depressive episode and anxiety. Quality of Life Research, 16(5), 749–754. doi:10.1007/s11136-006-9159-z.

Whynes, D. K., McCahon, R. A., Ravenscroft, A., Hodgkinson, V., Evley, R., & Hardman, J. G. (2013). Responsiveness of the EQ-5D health-related quality-of-life instrument in assessing low back pain. Value in Health, 16(1), 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.09.003.

Drummond, M. (2001). Introducing economic and quality of life measurements into clinical studies. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 344–349. doi:10.3109/07853890109002088.

Szende, A., Janssen, B., & Cabases, J. (Eds.). (2014). Self-reported population health: An international perspective based on EQ-5D. Dordrecht Heidelberg: Springer Open.

Norman, G. R., Gwadry Sridhar, F., Guyatt, G. H., & Walter, S. D. (2001). Relation of distribution- and anchor-based approaches in interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life. Medical Care, 39(10), 1039–1047.

Soer, R., Reneman, M. F., Speijer, B. L. G. N., Coppes, M. H., & Vroomen, P. C. A. J. (2012). Clinimetric properties of the EuroQol-5D in patients with chronic low back pain. The Spine Journal, 12(11), 1035–1039. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2012.10.030.

Walters, S. J., & Brazier, J. E. (2003). What is the relationship between the minimally important difference and health state utility values? The case of the SF-6D. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 4. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-4.

König, H.-H., Born, A., Günther, O., Matschinger, H., Heinrich, S., Riedel-Heller, S. G., et al. (2010). Validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D in assessing and valuing health status in patients with anxiety disorders. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 47. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-8-47.

Kvam, A. K., Fayers, P. M., & Wisloff, F. (2011). Responsiveness and minimal important score differences in quality-of-life questionnaires: A comparison of the EORTC QLQ-C30 cancer-specific questionnaire to the generic utility questionnaires EQ-5D and 15D in patients with multiple myeloma. European Journal of Haematology, 87(4), 330–337. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01665.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsiplova, K., Pullenayegum, E., Cooke, T. et al. EQ-5D-derived health utilities and minimally important differences for chronic health conditions: 2011 Commonwealth Fund Survey of Sicker Adults in Canada. Qual Life Res 25, 3009–3016 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1336-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1336-0