Abstract

Objective

To estimate the minimum important difference (MID) for a variety of mapped utility measures and to determine whether patients perceiving gains and losses in health status should be treated equally when calculating the MID.

Methods

A longitudinal study within a California managed care population of 6,932 patients was retrospectively analyzed. Utilities were derived from the SF-36 short-form health survey using multiple validated mapping methods. Absolute utility changes for patients who considered their current health as ‘somewhat better’ or ‘somewhat worse’ in the prior year were compared to determine if gains and losses in utility values could be combined. The MIDs were calculated and compared using anchor- and distribution-based methods.

Results

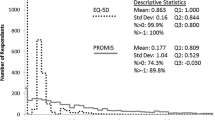

Two thousand one hundred patients reported ‘somewhat better’ or ‘somewhat worse’ health in the first year. When combining these patients, the average MID for all mapped utility measures was 0.03 (SD = 0.1), a magnitude similar to that identified by Walters. However, when separated, the mean MID utility change for those reporting ‘somewhat better’ and ‘somewhat worse’ health was 0.02 (SD = 0.1) and −0.06 (SD = 0.1), respectively (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Researchers should consider the effects of combining gains and losses when determining utility MID values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CDS:

-

Chronic Disease Score

- CEA:

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis

- ES:

-

Effect size

- FACT:

-

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- HrQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- HUI2:

-

Health Utilities Index Mark 2

- MID:

-

Minimum important difference

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life year

- SEM:

-

Standard error of measurement

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SG:

-

Standard gamble

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

References

Food and Drug Administration. (FDA) (2006). Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcomes measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. FDA, Rockville, MD. Available online at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/5460dft.pdf#search=%91draft%20guidance%20fda%20patient%20reported%20outcomes’

Torrance, G. W., & Feeny, D. (1989). Utilities and quality-adjusted life years. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 5, 559–575.

Gold, M. R., Siegel, J. E., Rusell, L. B., & Weinstein, M. C. (1996). Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wyrwich, K. W., Bullinger, M., Aaronson, N., Hays, R. D., Patrick, D. L., & Symonds, T. (2005). Estimating clinically significant differences in quality of life outcomes. Quality of Life Research, 14, 285–295. doi:10.1007/s11136-004-0705-2.

Lydick, E., & Epstein, R. S. (1993). Interpretation of quality of life changes. Quality of Life Research, 2, 221–226. 10.1007/BF00435226.

Revicki, D. A., Cella, D., Hays, R. D., Sloan, J. A., Lenderking, W. R., & Aaronson, N. K. (2006). Responsiveness and minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 70–74. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-70.

Kazis, L. E., Anderson, J. J., & Meenan, R. F. (1989). Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Medical Care, 27(Suppl.), S178–S189. doi:10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015

Wyrwich, K. W., Tierney, W., & Wolinsky, F. D. (1999). Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 52, 861–873. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00071-2.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edn.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A., & Wyrwich, K. W. (2003). Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care, 14(5), 582–592. doi:10.1097/00005650-200305000-00004.

Ross, M. (1989). Relation of implicit theories to the construction of personal histories. Psychological Review, 96, 341–357. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.341.

Guyatt, G. H., Norman, G. R., Juniper, E. F., & Griffith, L. E. (2002). A critical look at transition ratings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55, 900–908. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00435-3.

Sprangers, M. A. G., & Schwartz, C. E. (1999). Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Social Science and Medicine, 48, 1507–1515. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00045-3.

Guyatt, G. H., Osoba, D., Wu, A. W., Wywrich, K. W., & Norman, G. R.; Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. (2002). Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 77(4), 371–383.

Walters, S. J., & Brazier, J. E. (2005). Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Quality of Life Research, 14, 1523–1532. doi:10.1007/s11136-004-7713-0.

Cella, D., Hahn, E. A., & Dineen, K. (2002). Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: Differences between improvement and worsening. Quality of Life Research, 11, 207–221. doi:10.1023/A:1015276414526.

Lundberg, L., Johannesson, M., Isacson, D. G. L., & Borgquist, L. (1999). The relationship between health-state utilities and the SF-12 in a general population. Medical Decision Making, 19(2), 128–140. doi:10.1177/0272989X9901900203.

Shmueli, A. (2004). The relationship between the visual analog scale and the SF-36 scales in the general population: An update. Medical Decision Making, 24(1), 61–63. doi:10.1177/0272989X03261562.

Von Korff, M., Wagner, E. H., & Saunders, K. (1992). A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 45, 197–203. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(92)90016-G.

Walters, S. J., & Brazier, J. E. (2003). What is the relationship between the minimally important difference and health state utility values? The case of the SF-6D. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 4–11. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-4.

Ware, J. E., & Kosinski, M. (2001). The SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales. A manual for users of version 1, 2nd edn. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated.

Brazier, J., Roberts, J., & Deverill, M. (2002). The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics, 21(2), 271–292. doi:10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8.

Nichol, M. B., Sengupta, N., & Globe, D. R. (2001). Evaluating quality-adjusted life years: Estimation of the health utility index (HUI2) from the SF-36. Medical Decision Making, 21, 105–112. doi:10.1177/02729890122062352.

Yost, K. J., Cella, D., Chawla, A., Holmgren, E., Eton, T., Ayanian, J. Z., West, D. W. (2005). Minimally important differences were estimated for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) instrument using a combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58, 1241–1251. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.008.

Pickard, A. S., Wang, Z., Walton, S. M., & Lee, T. A. (2005). Are decisions using cost-utility analyses robust to choice of SF-36/SF-12 preference-based algorithm? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 3, 11–19. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-3-11.

Brissette, I., Leventhal, H., & Leventhal, E. A. (2003). Observer ratings of health and sickness: Can other people tell us anything about our health that we don’t already know? Health Psychology, 22, 471–478. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.471.

Brissette, I., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 102–111. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.102.

Wyrwich, K. W., Metz, S. M., Babu, A. N., Kroenke, K., Tierney, W. M., & Wolinsky, F. D. (2002). The reliability of retrospective change assessments. Quality of Life Research, 11(7), 636.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nichol, M.B., Epstein, J.D. Separating gains and losses in health when calculating the minimum important difference for mapped utility measures. Qual Life Res 17, 955–961 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9369-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9369-7