Abstract

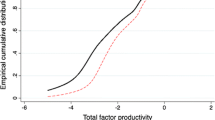

Hayashi and Prescott (Rev Econ Dyn 5(1):206–235, 2002) argue that the ‘lost decade’ of the 1990s in Japan is explained by the slowdown in exogenous TFP growth rates. At the same time, other research suggests that Japanese banks’ support for inefficient firms prolonged recessions by reducing productivity through misallocation of resources. Using the data on large manufacturing firms between 1969 and 1996, the paper attempts to disentangle the factors behind the slowdown in productivity growth during the 1990s. The main results show that there was a significant drop in within-firm productivity, the component that is not affected by reallocation of input and output shares across firms over time, during the 1990s. Although we find that misallocation among large continuing firms represents a substantial drag to overall TFP growth for these firms throughout the sample period, the negative impact of misallocation was least visible during the 1990s. The significant reduction in within-firm productivity growth suggests that, as the Japanese economy has matured, a policy which fosters technological innovations via greater competition, R&D, and fast technological adoption may have become increasingly important in promoting economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There has been a growing number of research related to this topic. For a formal theoretical presentation and an excellent literature review, see Caballero et al. (2008).

Woo (2003) finds similar results.

In these models, entrants start with the highest level of productivity and incumbents exit when their productivity levels become too low relative to the latest technology of entrants. These models are convenient for analytical tractability, especially for understanding the role that reallocation plays in productivity dynamics. However, entrants’ high productivity assumption may be too restrictive in general, as entrants often go through a phase of experimentation and many of them are expected to fail during the process, before becoming productive. For example, see Jovanovic (1982).

Unfortunately, a dataset as comprehensive as the Longitudinal Research Database has not yet been made available. Therefore, a comparison of productivity dynamics across time periods using a more complete establishment level dataset is not yet possible.

Using Basic Survey on Business Activities by Enterprizes, a firm level dataset constructed by Japanese Ministry of Trade and Industry, Fukao et al. (2003) also finds that the exit component negatively contributed to overall productivity growth between 1996 and 1998 in the manufacturing sector, indicating that least efficient firms stayed in business.

The prior studies on productivity decomposition in Japan, as in Fukao et al. (2003), use a more comprehensive dataset, but focus only on the 1990s due to the unavailability of a longer series. As a result, we cannot examine if the characteristics observed are uniquely attributed to the 1990s.

However, we feel that the examination of entry component deserves some attention, as much of the discussion regarding the role of reallocation in Japan during the 1990s involved problems in the financial sector. An additional sense in which new IPO entrants relate to Shumpeter’s creative-destruction theory is that new IPO entrants challenge older firms for access to capital. If firms capable of negotiating a successful IPO are on average more productive than their counterparts, a similar creative-destruction mechanism through entry and exit may apply.

We used internet resources such as Teikoku databank (http://www.tdb.co.jp) to confirm bankruptcy of the firms for which the merger index does not indicate incidence of a merger. We could not confirm the bankruptcy of 15 (out of 41) firms. Consequently, we excluded these firms from the exit component. See Appendix for the list of these firms.

Only firms listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) were included in 1964. Firms listed on Osaka and Nagoya stock exchanges were incorporated in 1970, other listed firms from smaller regional stock markets were incorporated in 1975, and leading unlisted companies submitting financial reports to the Ministry of Finance or reports to their shareholders were added in 1977.

Moreover, note that since we use firm-level dataset, we cannot observe the impact of reallocation activities across establishments within continuing firms. Productivity improvement associated with reshuffling of resources across establishments within a firm will show up in within-firm effect.

As explained in the Appendix, the rubber industry is excluded from the decomposition for the lack of a deflator. Moreover, short-lived firms which entered and exited within each time interval are excluded. In addition, some firms are excluded from the exit component since we could not confirm their bankruptcies. The list of these firms are provided in the Appendix.

The annual average employment is used for firms which submit reports semi-annually.

For instance, a measurement error in labor input generates spuriously high negative correlation between the change in share and labor productivity growth. This, in turn, raises the within-firm component. Similarly, a measurement error in output, in the case of conducting decomposition with TFP for instance, generates a spuriously high positive correlation between the change in share and TFP growth. This reduces the within-firm component. Since the second method uses average figures, it is less sensitive to this type of measurement error.

Adjustment of hours is needed in order to take into account the decline in work hours over time during the sample period. In many sectors within manufacturing, the average work hours declined steadily between 1960 and 1975, rose slightly between 1975 and 1990, and fell again after 1990 in response to changes in the Labor Standards Law which gradually reduced statutory work hours from 48 to 40.

Again, material input values are summed over each year for firms which submit reports more than once a year.

Excluding the Rubber industry, the entire manufacturing sector is divided into 87 industries based on the NEEDS three-digit industry classification.

The number of firms are smaller for TFP productivity decomposition compared to labor productivity decomposition, as some firms did not have complete information to construct TFP.

The aggregate data also shows that the total number of corporate bankruptcies was particularly low during the 1988–1996 period, implying that businesses were able to ride out the initial stage of the recession. The data on total number of corporate bankruptcies can be obtained from the publications of Tokyo Shoko Research, Ltd. The following site (in Japanese) provides the number of corporation bankruptcies since 1952: http://www.tsr-net.co.jp/new/zenkoku/transit/index.html.

On the other hand, measurement problems in labor input and labor hoarding would affect both labor productivity and TFP.

Using Hayashi and Prescott’s measure of aggregate TFP, the overall growth rates of TFP during 1969–1979, 1979–1988 and 1988–1996 periods are, respectively, 5.9, 5 and 4.1%. The overall TFP growth of our sample is higher than the aggregate TFP growth except during the 1979–1988 period. The exception during the 1979–1988 period is probably due to the computational method used: compared to the standard method of calculating TFP in which outputs and inputs are summed over businesses, our method of using weighted average seems to depress the TFP growth rate only during the 1979–1988 period. Since our sample consists of large manufacturing firms, the observed difference is consistent with the view that service sector TFP growth lags behind the TFP growth of manufacturing sector in Japan.

The main difference in the reallocation dynamics between the labor productivity and TFP decompositions is observed in the signs of between-firm and cross-firm components. If we use output as firm weight, both decompositions show that the cross-firm term is mostly positive (except for the TFP decomposition during the bubble period). Similarly, if we use employment as weight, both decompositions show that the cross-firm term is negative. However, the combined effect of reallocation shows similar qualitative results regardless of the weight used.

A similar pattern was observed in Foster et al. (2001): They also find that labor reallocation among continuing firms also plays a small but negative role.

The results of the decomposition by output size is similar to the capital stock results.

One possible explanation is high level of employment protection, since it would interfere with the reallocation process especially for labor intensive firms.

There are a couple of, possibly more, explanations for the difference. One is that businesses with small capital stock did not use, or have access to, the capital that generated high growth. The differences in the types of capital will be captured in TFP since we use one type of deflator for all capital stocks, and furthermore, capital stocks are not deflated based on their vintages.

While a subsidy for labor hoarding exists in Japan (Employment Adjustment Subsidy), only a small fraction of manufacturing workers were covered by the subsidy, despite the wide eligibility coverage of manufacturing establishments during this period. The take-up of this subsidy was particularly high in the Iron and Steel industry. For more information on this subsidy as well as its theoretical implications, see Griffin (2005).

If the effect of reallocation on aggregate productivity can go beyond the changes in input and output shares, we need a set of models that explain the interaction between reallocation and within-firm productivity dynamics. A paper by Aghion et al. (2005) asks this question by examining how entry threat spurs innovation incentives. They argue that entry threat promotes innovation in technologically advanced industries, while the opposite is the case in laggard sectors.

These data are formatted and made available at the Bank of Japan’s website. English site for CGPI can be found at http://www2.boj.or.jp/en/dlong/dlong.htm.

These data as well as other major Japanese labor statistics are formatted and made available by the Japan Institute for Labor Policy and Training, in Japanese, at the following website: http://stat.jil.go.jp.

This substitution should not be a problem since the correlations of hours across sectors are very high.

Note that the standard errors of the annual contributions are quite large because of the high level of volatility at annual frequency.

References

Aghion P, Howitt P (1992) A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica 60(2):323–351

Aghion P, Blundell R, Griffith R, Howitt P, Prantl S (2005) The effects of entry on incumbent innovation and productivity. Discussion Paper No. 5323, Center for Economic Policy Research, London.

Caballero R, Hammour M (1994) The cleansing effect of recessions. Am Econ Rev 84(5):1350–1368

Caballero R, Hammour M (1996) On the timing and efficiency of creative destruction. Q J Econ 111(3):805–852

Caballero R, Hoshi T, Kashyap AK (2008) Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan. Am Econ Rev 98(5):1943–1977

Foster L, Haltiwanger J, Krizan CJ (2001) Aggregate productivity growth: lessons from microeconomic evidence. In: Dean E, Harper M, Hulten C (eds) New development in productivity analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 303–363

Foster L, Haltiwanger J, Krizan CJ (2002) The link between aggregate and micro productivity growth: evidence from retail trade. Working Paper No. 9120, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

Fukao K, Inui T, Kawai H, Miyagawa T (2003) Sectoral productivity and economic growth in Japan, 1970–98: an empirical analysis based on the JIP database. Discussion Paper No. 67, Economic and Social Research Institute, Cabinet Office

Griffin NN (2005) Labor adjustment, productivity and output volatility: an evaluation of Japan’s employment adjustment subsidy. Working Paper No. 2005-10, Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC

Hamao Y, Mei J, Xu Y (2003) Idiosyncratic risk and the creative destruction in Japan. Working Paper No. 9642, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

Hayashi F, Prescott EC (2002) The 1990s in Japan: a lost decade. Rev Econ Dyn 5(1):206–235

Jovanovic B (1982) Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica 50(3):649–670

Motonishi T, Yoshikawa H (1999) Causes of the long stagnation of Japan during the 1990s: financial or real? J Jpn Int Econ 13(3):181–200

Peek J, Rosengren ES (2005) Unnatural selection: perverse incentives and the misallocation of credit in Japan. Am Econ Rev 95(4):1144–1166

Woo D (2003) In search of ‘capital crunch’: supply factors behind the credit slowdown in Japan. J Money Credit Bank 35(6):1019–1038

Acknowledgements

We thank John Haltiwanger, John Shea, Michael Pries, Katherine Abraham, Nathan Musick, anonymous referees and associate editor for invaluable comments and suggestions. The analysis and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as those of the Congressional Budget Office or the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Construction of variables using the NEEDS database

The total sales revenue (NEEDS item #90) is used as a measure of gross output. Nominal value of sales is deflated into a constant year 2000 value, using the annual averages of monthly Corporate Goods Price Indices (CGPI) for two-digit manufacturing industries, constructed by the Bank of Japan. Footnote 28 Because the CGPI for the rubber industry (NEEDS industry code #13) was not available, it was omitted from the analysis. Moreover, the CGPI for the nonferrous metals industry is used for the nonferrous metals and metal products industry (NEEDS industry code #19). Similarly, total material cost (NEEDS item #292) is deflated, using the CGPI, and is used as a measure of material input. The material and labor cost shares are calculated, respectively, by dividing total material cost (NEEDS item #292) and total labor cost (NEEDS item #293) by total cost (NEEDS item #306).

The number of employed workers (NEEDS item #158) is used as the measure of employment. To construct a measure of labor input, the number of employed workers is multiplied by average monthly work hours, by two-digit manufacturing industry, taken from Monthly Labor Survey, published by Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. Footnote 29 Note that Monthly Labor Survey does not have a category “pharmaceutical” for the sample period, and the category “other manufacturing” starts in 1986. Accordingly, average monthly work hours of the entire manufacturing sector are used for these sectors. Footnote 30 Moreover, the category “transportation equipment” is used for all sectors related to transportation in the NEEDS database.

The measure of capital stock is constructed using the total tangible assets (NEEDS item #21) of the NEEDS database, which is the sum of buildings (NEEDS item #23), machineries (NEEDS item #24), transportation equipment (NEEDS item #25), other equipment (NEEDS item #26), land (NEEDS item #27), and others (NEEDS item #28). According to NEEDS item #260, the method of depreciation for tangible assets, most observations use a constant rate of depreciation, some use a combination of the constant rate and the constant value, and a very small fraction use a combination of constant rate, constant value, and the rate of depreciation proportional to output. These figures then are converted to a constant year 1995 value, using the annual average of the monthly wholesale price index (WPI) for machinery and equipment, provided by the Bank of Japan. The WPI is available at the Bank of Japan’s website.

1.2 Lists of exiting firms

Table 5 lists the exiting firms that are used for the productivity decomposition. Table 6 lists firms that are excluded from the exit group because internet resources indicated existence of those firms after the year of disappearance from the NEEDS database. We determined that some of the firms had mergers (Azuma Steel, Toshin Steel, and Toyo Pulp) even though the merger index did not indicate incidence of a merger; however, we did not include these firms in the merger group because of the concern that it would create an inconsistency in the selection of firms in the merger group.

1.3 Annual productivity growth decomposition

This section presents the results of the productivity decomposition exercises using annual productivity growth rates. The resulting annual share figures are averaged across three subperiods as described in the main text. Table 7 gives the results of annual TFP growth decomposition. The main results are essentially the same. However, one noteworthy point is that, for the annual average share, the within-firm TFP component does not fall during the bubble-economy period. Consequently, the drop in within-firm TFP is a salient feature of the post-bubble period. Footnote 31

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Griffin, N.N., Odaki, K. Reallocation and productivity growth in Japan: revisiting the lost decade of the 1990s. J Prod Anal 31, 125–136 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-008-0123-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-008-0123-5