Abstract

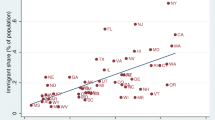

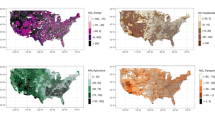

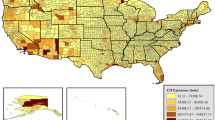

This paper investigates the immigration–environment association using U.S. county-level data, for a subset of counties (N = ~200), and a model inspired by the STIRPAT approach. The analysis makes use of U.S. census data for the year 2000 reflecting U.S.-born and foreign-born populations, combined with county-level data reflecting emissions of CO2, NO2, PM10, and SO2. With a focus on approximately 200 primarily urban counties for which complete data are available, and after controlling for income, employment in the utilities and manufacturing sectors, and coal consumption for SO2 estimations, few statistically significant associations emerge between population composition and emissions. Counties with a relatively larger U.S.-born population have higher NO2 and SO2 emissions. On the other hand, counties with a relatively higher number or share of foreign-born residents have lower SO2 emissions. Although limited to cross-sectional analyses, the results provide a foundation for future longitudinal research on this important and controversial topic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The connotations foreign population, foreign-born, and immigrants that are used in this paper are defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as “anyone who is not a U.S. citizen at birth. This includes naturalized U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents (immigrants), temporary migrants (such as foreign students), humanitarian migrants (such as refugees), and people illegally present in the United States.”

The EPA reports six air pollutants, the other two ground-level ozone and lead. These two are excluded from the analysis since ground level ozone is generally problematic only in the summer season and lead is specific to lead smelters and various stationary sources.

The full data set is available at http://www.epa.gov/airtrends/aqtrnd00/pdffiles/county00.pdf.

Further information about air pollutants are available at http://www.epa.gov/air/urbanair/.

Per capita GDP data are not available at the county level.

Previous research has typically used sector-based per capita GDP. However, such data are not available at the county level.

Unfortunately, such data are neither available for 2000 nor at the county level.

See e.g. York et al. (2003) for CO2 and Cole and Neumayer (2004) for CO2 and SO2. CO2 is not included in this study because it is generally perceived as a global externality (Frankel and Rose 2005). The use of total emissions in lieu of emissions per capita is consistent with Cole and Neumayer (2004).

The introduction of income squared is consistent with Frankel and Rose (2005).

I would like to thank an anonymous referee for this insight.

References

BALANCE. (1992). Why excess immigration damages the environment. Population and Environment, 13, 303–312.

Been, V. (1994). Locally undesirable land uses in minority neighborhoods: Disproportionate siting or market dynamics? The Yale Law Journal, 103, 1383–1422.

Borjas, G. J. (1994). The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32, 1667–1717.

Borjas, G. J. (1995). The economic benefits from immigration. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9, 3–22

Bullard, R. D. (1990). Dumping in dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Card, D. (2001). Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local market impacts of higher immigration. Journal of Labor Economics, 19, 22–64.

Chapman, R. L. (2006). Confessions of a Malthusian restrictionist. Ecological Economics, 59, 214–219.

Cohen, J. (1995). How many people can the earth support? Norton & Company, London.

Cole, M. A., & Neumayer, E. (2004). Examining the impact of demographic factors on air pollution. Population and Environment, 26, 5–21.

Daily, G., Ehrlich, A., & Ehrlich, P. (1994). Optimum human population size. Population and Environment, 15, 469–475.

Dietz, T., & Rosa, E. A. (1994). Rethinking the environmental impacts of population, affluence and technology. Human Ecology Review, 1, 277–300.

DinAlt, J. (1997). The environmental impact of immigration into the United States, carrying capacity network’s focus 4, http://www.carryingcapacity.org/DinAlt.htm.

Espenshade, T. J., & Hempstead, K. (1996). Contemporary American attitudes toward U.S. immigration. International Migration Review, 30: 535–570.

Executive Office of the President. (2007). Immigration’s economic impact, Council of Economic Advisers, Washington, DC, http://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/cea immigration 062007.pdf.

Frankel, J. A., & Rose, A. (2005). Is trade good or bad for the environment? Sorting out the causality. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 87, 85–91.

Hamilton, L. C. (2009). Statistics with STATA. Belmont. CA: Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning

Huber, P. J. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (Vol. 1, pp. 221–223). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Huddle, D. (1993). The costs of immigration. Unpublished manuscript, Rice University.

Hunter, L. M. (2000a). A comparison of the environmental attitudes, concern, and behaviors of native-born and foreign-born US Residents. Population and Environment, 21, 565–580.

Hunter, L. M. (2000b). The spatial association between U.S. immigrant residential concentration and environmental hazards. The International Migration Review, 34, 460–488.

Johnson, K. M., & Lichter, D. T. (2008). Natural increase: A new source of population growth in emerging hispanic destinations in the United States. Population and Development Review, 34, 327–346.

Kremer, M. (1993). Population growth and technological change: One million b.c. to 1990. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108, 681–716.

Muradian, R. (2006). Immigration and the environment: Underlying values and scope of analysis. Ecological Economics, 59, 208–213.

Neumayer, E. (2006). The environment: One more reason to keep immigrants out Ecological Economics, 59, 204–207.

Ohlemacher, S. (2007). Number of immigrants hits record 37.5M, Washington Post, September 12, 2007.

Ottaviano, G. I. P., & Peri, G. (2005). Rethinking the gains from immigration: Theory and evidence from the U.S., NBER Working Paper No. 11672.

Passel, J. S., & Clark, J. L. (1994). How much do immigrants really cost? A reappraisal of huddle’s ‘The cost of immigrants.’ Unpublished manuscript, Urban Institute.

Pfeffer, M. J., & Stycos, J. M. (2002). Immigrant environmental behaviors in New York City. Social Science Quarterly, 83, 1, 64–81.

Pimentel, D., Giampietro, M., & Bukkens, S. (1998). An optimum population for North and Latin America. Population and Environment, 20, 125–148.

Smith, J. P., & Edmonston, B. (Eds.). (1997). The new Americans: Economic, demographic, and fiscal effects of immigration. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2001). State of World Population 2001, Footprints and Milestones: Population and Environmental Change, http://www.unfpa.org/swp/2001/english/index.html.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–830.

York, R., Rosa, E. A., & Dietz, T. (2003). STIRPAT, IPAT, and ImPACT: Analytic tools for unpacking the driving forces of environmental impacts. Ecological Economics, 46, 351–365.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Lori Hunter for constructive comments and suggestions. My sincere thanks also go to four anonymous referees for helpful comments. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Squalli, J. Immigration and environmental emissions: A U.S. county-level analysis. Popul Environ 30, 247–260 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0089-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0089-x