Abstract

Despite the plethora of studies demonstrating that economic perceptions affect how a person votes, relatively little is known about how economic perceptions affect whether individuals will vote. Using the calculus of voting as our starting point, we develop a simple, but novel, hypothesis regarding the influence of sociotropic evaluations on voter turnout. We argue that this relationship will be curvilinear, with particularly negative and particularly positive evaluations of the economy increasing the likelihood of voting. Using an instrumental variables approach with individual-level data from eight recent U.S. presidential elections, we find that economic evaluations affect the decision to vote in the curvilinear manner hypothesized, but—counter to existing theory—only when there is not an incumbent president seeking reelection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Killian et al. (2008) are an exception here, as they examine the interaction between pocketbook and sociotropic evaluations.

One might consider whether retrospective contributions to the B and D terms of the calculus of voting are symmetrical, meaning that voters are equally affected by both positive and negative economic evaluations. Symmetry is a reasonable assumption for the retrospective component of the instrumental benefits (B), but it is plausible that there is an asymmetry to a retrospective voter’s expressive benefits (D). Voters may accrue greater expressive benefits from blaming incumbents for poor economic performance than from crediting them for positive economic gains. This type of asymmetric utility function would then mean that particularly poor evaluations should lead to a greater probability of voting then particularly positive evaluations, all else equal. Unfortunately, we cannot satisfactorily explore this possibility with our data due to the relative scarcity of highly positive evaluations of the economy. There is not sufficient information in the data to identify properly (with our IV model) any differences in the effect of very positive and very negative economic evaluations on turnout.

The 1948–2008 ANES Cumulative Data File was produced and distributed by Stanford University and the University of Michigan, 2010. These materials are based on work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos.: SBR-9707741, SBR-9317631, SES-9209410, SES-9009379, SES-8808361, SES-8341310, SES-8207580, and SOC77-08885.

The respondent’s county of residence is required for the creation of our instrument of the respondent’s sociotropic evaluation but is only publicly available through 1996. For more recent elections, we obtained county codes after filing an ANES Restricted Data Access Application.

We use a quadratic specification here primarily because in its full form it allows greater flexibility in terms of capturing the relationship between Sociotropic Evaluation and Turnout than by simply folding Sociotropic Evaluation. For example, the full quadratic specification allows for the possibility of a linear relationship (i.e., a non-zero coefficient for Sociotropic Evaluation and a coefficient of zero for Sociotropic Evaluation 2), which we do not hypothesize but exists as a rival hypothesis in the literature. Nonetheless, we assessed whether our inferences remain the same if we use a folded version of Sociotropic Evaluation in our IV model. The results are very similar, as might be expected. The estimate for the folded variable is positive and significant while its interaction with Incumbent is negative and significant.

An alternative approach is to split the data by the two different types of election; those with an incumbent candidate and those without. We can then estimate separate models for each set of elections, thus removing the need for the Incumbent interaction term altogether. As reported in the Supplemental Information (see Table S7), the inferences resulting from this approach are the same as those obtained with the pooled models with the interaction terms.

Female, Black, Latino, Asian, Unemployed, Married, Union Member, and Party Contact are dummy variables. Age is measured in years. Education is a seven-category ordinal scale of the respondents’ self-reported educational attainment. Income is a five-point ordinal scale indicating the respondent’s family income percentile at the time of the survey, where the categories are 0–16, 17–33, 34–67, 68–95, and 96–100. Roughly 7.5 % of the income percentile data were missing and thus imputed—details are available from the authors. Religiosity is a composite of three ANES variables (VCF0130, VCF0130a, and VCF0131) that measure respondents’ church attendance. The three variables, which ANES used at different points in time, were collapsed into four temporally-consistent categories. Strength of Party ID is generated by folding the seven-point party ID scale so that larger values represent stronger partisan identification.

Registration Closing Date is measured as the number of days between the last day to register to vote and Election Day.

The set of control variables excludes psychological correlates of turnout, such as trust in government and external efficacy, because they may be endogenous to Sociotropic Evaluation, making their inclusion in the first-stage model problematic. In addition, the inclusion of the ANES trust and external efficacy variables causes a loss of more than 1,000 observations.

One might argue that, instead of using an instrument, the effect of Sociotropic Evaluation can be modeled as being conditional on the partisanship of the potential voter. This would be a viable option if (1) partisanship was the only source of endogeneity here and (2) we could perfectly measure partisanship. Unfortunately, we believe it is highly unlikely that the data meet either of these assumptions, let alone both.

County-level unemployment data were provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The BLS provides “official” civilian labor force data from 1990 to 2009 online at the U.S. Census Bureau’s “USA Counties” website (http://censtats.census.gov/usa/usa.shtml). Data from 1976 to 1989 are deemed “unofficial” because they were estimated under an alternative methodological strategy. These data are available for purchase from the BLS. Our analyses show no discernible structural break in the estimates due to BLS’s methodological changes. County-level per capita personal income data were provided by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&isuri=1&acrdn=5).

Kiewiet and Rivers (1984, pp. 384–385) acknowledge both the prospect of endogeneity and the role of objective local conditions in forming individuals’ perceptions of the national economy:

“We suspect that cross-sectional variation in perceptions of national economic trends arises from many sources. Some of it will be partisan rationalization, but some of it may reflect different sources of information available to voters. For example, in depressed areas voters may perceive national conditions to be worse than do voters in booming areas”.

We cannot simply include these squared predicted values in the main equation. Instead, they must be treated as an instrument in the first stage models (Wooldridge 2002, pp. 236–237).

The Supplemental Information presents Models 1.3 and 1.4 estimated by probit instead of OLS (see Table S6).

The estimates for the control variables are presented in the Supplemental Information (Tables S4 and S5).

Given our clear theoretical expectation for the direction of the estimates for Sociotropic Evaluation 2 we employ one-tailed significance tests for this pair of estimates. For all other coefficient estimates, we use two-tailed tests.

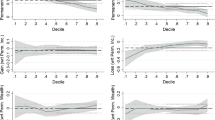

In Model 1.1, for example, the conditional coefficient or effect for Sociotropic Evaluation 2 is .374 when there is not an incumbent candidate and −.005 when there is an incumbent candidate. The former conditional coefficient is statistically significant while the latter is not. See Brambor et al. (2006) for a discussion of conditional coefficients and standard errors.

An analysis of the effect of objective national economic conditions over a longer time span yields results that are consistent with our IV models, providing reassurance that this somewhat counterintuitive result is not driven by the eight elections under analysis in our IV models. See the Supplemental Information for this alternative research design and results (Table S8).

This has no implication for the substantive effect sizes displayed, since these predictions are generated with a 2SLS model instead of a probit model.

We cannot add elections before 1972 because we lack the requisite county-level data. For the 1972 election, we use three-year change in a county’s median income because the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ county-level data begin in 1969.

The BLS county-level data date back to 1976, which limits our use of Δ County Unemployment to 1980 onward.

References

Angrist, J. D. (2001). Estimation of limited dependent variable models with dummy endogenous regressors: Simple strategies for empirical practice. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 19(1), 2–16.

Angrist, J. D., Imbens, G. W., & Rubin, D. B. (1996). Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91(434), 444–455.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ansolabehere, S., & Jones, P. E. (2010). Constituents’ responses to congressional roll-call voting. American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 583–597.

Arcelus, F., & Meltzer, A. M. (1975). The effect of aggregate economic variables on congressional elections. American Political Science Review, 69(4), 1232–1239.

Arceneaux, K. (2003). The conditional impact of blame attribution on the relationship between economic adversity and turnout. Political Research Quarterly, 56(1), 67–75.

Books, J., & Prysby, C. (1991). Contextual effects on retrospective economic evaluations: The impact of the state and local economy. Political Behavior, 21(1), 1–16.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82.

Brennan, G., & Hamlin, A. (1998). Expressive voting and electoral equilibrium. Public Choice, 95(1–2), 149–175.

Brennan, G., & Lomasky, L. (1993). Democracy and decision: The pure theory of electoral preferences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Caldeira, G. A., Patterson, S. C., & Markko, G. A. (1985). The mobilization of voters in congressional elections. Journal of Politics, 47(2), 490–509.

Darmofal, D. (2010). Reexamining the calculus of voting. Political Psychology, 31(2), 149–174.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Duch, R. M., Palmer, H. D., & Anderson, C. J. (2000). Heterogeneity in perceptions of national economic conditions. American Journal of Political Science, 44(4), 635–652.

Eisenberg, D., & Ketcham, J. (2004). Economic voting in U.S. presidential elections: Who blames whom for what. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 4(1), Article 19.

Evans, G., & Anderson, R. (2006). The political conditioning of economic perceptions. Journal of Politics, 68(1), 194–207.

Evans, G., & Pickup, M. (2010). Reversing the causal arrow: The political conditioning of economic perceptions in the 2000–2004 U.S. presidential election cycle. Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1236–1251.

Fiorina, M. P. (1976). The voting decision: Instrumental and expressive aspects. Journal of Politics, 38(2), 390–413.

Fiorina, M. P. (1978). Economic retrospective voting in American national elections: A micro-analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 22(2), 426–443.

Gomez, B. T., & Wilson, J. M. (2001). Political sophistication and economic voting in the American electorate: A theory of heterogeneous attribution. American Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 899–914.

Hamlin, A., & Jennings, C. (2011). Expressive political behaviour: Foundations, scope and implications. British Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 645–670.

Hansford, T. G., & Gomez, B. T. (2011). Reevaluating the sociotropic economic voting hypothesis. Working paper.

Highton, B. (2004). Voter registration and turnout in the United States. Perspectives on Politics, 2(3), 507–515.

Holbrook, T. M. (1991). Presidential elections in space and time. American Journal of Political Science, 35(1), 91–109.

Jackman, R. W. (1987). Political institutions and voter turnout in industrial democracies. American Political Science Review, 81(2), 405–423.

Kiewiet, D. R., & Rivers, D. (1984). A retrospective on retrospective voting. Political Behavior, 6(4), 369–393.

Killian, M., Schoen, R., & Dusso, A. (2008). Keeping up with the Joneses: The interplay of personal and collective evaluations in voter turnout. Political Behavior, 30(3), 323–340.

Kinder, D. R., & Kiewiet, D. R. (1981). Sociotropic politics: The American case. British Journal of Political Science, 11(2), 129–161.

Kramer, G. H. (1971). Short-term fluctuations in U.S. voting behavior, 1896–1964. American Political Science Review, 65(1), 131–143.

Leighley, J. E., & Nagler, J. (1992). Socioeconomic class bias in turnout, 1964–1988: The voters remain the same. American Political Science Review, 86(3), 725–736.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Nadeau, R., & Elias, A. (2008). Economics, party, and the vote: Causality issues and panel data. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 84–95.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Paldam, M. (2000). Economic voting: An introduction. Electoral Studies, 19(2–3), 113–121.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 183–219.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Stubager, R., & Nadeau, R. (2013). The Kramer problem: Micro-macro resolution with a Danish pool. Electoral Studies, 32(3), 500–505.

Markus, G. B. (1988). The impact of personal and national economic conditions on the presidential vote: A pooled cross-sectional analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 33(1), 137–154.

Miguel, E., Satyanath, S., & Sergenti, E. (2004). Economic shocks and civil conflict: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Political Economy, 112(4), 725–753.

Miller, A. H., & Wattenberg, M. P. (1985). Throwing the rascals out: Policy and performance evaluations of presidential candidates, 1952–1980. American Political Science Review, 79(2), 359–372.

Nadeau, R., & Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2001). National economic voting in U.S. presidential elections. Journal of Politics, 63(1), 159–181.

Nisbett, R., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Norpoth, H. (2002). On a short leash: Term limits and the economic voter. In H. Dorussen & M. Taylor (Eds.), Economic voting. London: Routledge.

Pacek, A. C. (1994). Macroeconomic conditions and electoral politics in East Central Europe. American Journal of Political Science, 38(3), 723–744.

Pickup, M., & Evans, G. (2013). Addressing the endogeneity of economic evaluations in models of political choice. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77(3), 714–734.

Radcliff, B. (1992). The welfare state, turnout, and the economy: A comparative analysis. American Political Science Review, 86(2), 444–454.

Riker, W. H., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1968). A theory of the calculus of voting. American Political Science Review, 62(1), 25–42.

Rosenstone, S. J. (1982). Economic adversity and voter turnout. American Journal of Political Science, 26(1), 25–46.

Rosenstone, S. J., & Hansen, J. M. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Rosenstone, S. J., & Wolfinger, R. E. (1978). The effect of registration laws on voter turnout. American Political Science Review, 72(1), 22–45.

Schlozman, K. L., & Verba, S. (1979). Injury to insult. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Staiger, D., & Stock, J. H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65(3), 557–586.

Verba, S., & Nie, N. H. (1972). Participation in America: Political democracy and social equality. New York: Harper & Row.

Wlezien, C., Franklin, M., & Twiggs, D. (1997). Economic perceptions and vote choice: Disentangling the endogeneity. Political Behavior, 19(1), 7–17.

Wolfinger, R. E., & Rosenstone, S. J. (1980). Who votes?. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this manuscript were presented at the 2010 and 2013 Annual Meetings of the Midwest Political Science Association. We would like to thank Jay Goodliffe and Robert Lowry for their helpful comments. Daniel Milton and Jim Martin, formerly of Florida State University, provided research assistance. This research was partially supported by a UC Merced Academic Senate Faculty Research Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gomez, B.T., Hansford, T.G. Economic Retrospection and the Calculus of Voting. Polit Behav 37, 309–329 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9275-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-014-9275-3