Abstract

Salicylic acid (SA) is a stress-induced hormone involved in the activation of defense genes. Here we analyzed the early genetic responses to SA of wild type and npr1-1 mutant Arabidopsis seedlings, using Complete Arabidopsis Transcriptome MicroArray (CATMAv2) chip. We identified 217 genes rapidly induced by SA (early SAIGs); 193 by a NPR1-dependent and 24 by a NPR1-independent pathway. These two groups of genes also differed in their functional classification, expression profiles and over-representation of cis-elements, supporting differential pathways for their activation. Examination of the expression patterns for selected early SAIGs from both groups indicated that their activation by SA required TGA2/5/6 subclass of transcription factors. These genes were also activated by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato AvrRpm1, suggesting that they might play a role in defense against bacteria. This study gives a global idea of the early response to SA in Arabidopsis seedlings, expanding our knowledge about SA function in plant defense.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Salicylic acid (SA) is a key hormone of stress defense responses induced by biotrophic pathogens in plants (Alvarez 2000; Durrant and Dong 2004; Loake and Grant 2007). These responses allow plants not only to survive pathogen infection, but also to acquire a long-lasting systemic resistance (SAR, systemic acquired resistance) responsible for the protection from further infections by a broad range of pathogens (Grant and Lamb 2006). Several lines of evidence give support to the idea that SA plays a key role in the establishment of SAR. Tissue levels of SA and its glucosylated conjugates (SAG) increase locally and systemically after pathogen infection (Summermatter et al. 1995). Conversely, blockade of SA accumulation severely impairs the deployment of SAR (Gaffney et al. 1993; Delaney et al. 1994; Wildermuth et al. 2001). Further supporting a direct role of SA in pathogen-induced resistance, a series of experiments showed that treatment of plant tissues with exogenous SA or its functional analogs BTH (benzothiadiazole S-methylester) and INA (2,6-dichoroisonicotinic acid), was sufficient to trigger a defense reaction resembling SAR, that protects plants against a further pathogen infection (Cao et al. 1994; Lawton et al. 1996).

The resistance to infection triggered by SA seems to be mainly due to its ability to activate defense genes. This is supported by the fact that mutants in some components of the transcriptional machinery activated by SA, such as the co-activator NPR1 (npr1 mutants) and the subclass II of TGA transcription factors (triple mutant tga2-2/tga5-1/tga6-1), are severely impaired to deploy SAR, either in response to SA/INA treatment, or to avirulent pathogens (Cao et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 2003). Interestingly, analysis of the tga2-2/tga5-1/tga6-1 triple mutant allowed the identification of TGA2, TGA5 and TGA6 as redundant factors involved in SA-mediated activation and basal repression of PR1 gene (Zhang et al. 2003). Impairment in SAR development, although less severe than that of npr1 and tga2/tga5/tga6 mutants, was also recently reported in mutants in the SA-activated WRKY 18, one of the members of the large family of WRKY transcription factors activated by pathogens (Wang et al. 2006).

Serious efforts have been done to characterize the pathogen-induced transcriptome of Arabidopsis (reviewed in (Katagiri 2004; Eulgem 2005; Glazebrook 2005). It is known that SA-induced genes (SAIGs) are an important part of this transcriptome, as revealed by the use of mutants in SA biosynthesis or signaling steps such as sid2, npr1 or nahG plants (Maleck et al. 2000; Glazebrook et al. 2003; Tao et al. 2003; Eulgem et al. 2004; Katagiri 2004; AbuQamar et al. 2006). Studies aimed at identifying and characterizing SAIGs that are important for defense reaction have focused mainly on genes that depend on the coactivator NPR1 (NPR1-dependent SAIGs) (Maleck et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2005, 2006). Some of the best-characterized NPR1-dependent SAIGs so far are the pathogenesis-related genes (PRs), a group of genes that code for proteins with antimicrobial activity (van Loon et al. 2006). PR-1, a member of this group, is the most common marker for this defense pathway (Maleck et al. 2000; van Loon et al. 2006). Furthermore, SAIGs coding for endoplasmic reticulum-localized proteins associated to the protein secretory machinery and for WRKY transcription factors involved in PR-1 activation, have been recently identified as primary targets of NPR1 involved in defense (Wang et al. 2005, 2006). Recently, two studies analyzing the response of Arabidopsis to short treatments with SA were published (Thibaud-Nissen et al. 2006; Krinke et al. 2007). One was performed in Arabidopsis cell suspensions and allowed the identification of SAIGs associated to the early activation of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (Krinke et al. 2007). The other study was performed in Arabidopsis plants and was oriented to identifying targets of TGA2 factor (Thibaud-Nissen et al. 2006).

Increasing evidence supports the idea that SA also plays a role in controlling the cellular redox balance at the onset of the SAR (Mou et al. 2003; Mateo et al. 2006; Holuigue et al. 2007). Treatment of Arabidopsis plants with INA produces a biphasic change of cellular redox potential (GSH/GSSG ratio): first a pro-oxidative effect and then an antioxidant effect of the SA analog (Mou et al. 2003). Associated to these changes, SA has been found to activate through a redox mechanism, NPR1, TGA1 (a member of the TGA family of bZIP transcription factors) and the SA-responsive as-1 promoter element (Garreton et al. 2002; Despres et al. 2003; Mou et al. 2003). In rice, SA has been proven essential for the protection of plants from oxidative stress caused by light, senescence, avirulent pathogens and treatment with methyl viologen (Yang et al. 2004). Consistently, in Arabidopsis, SA was required to restrict the oxidative stress and foster plant acclimation after transient exposure to high light intensity (Mateo et al. 2006). Interestingly, we and others found that SA uses a transient kinetics to activate genes coding for detoxifying or antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and glycosyltransferases (GTs) (Wagner et al. 2002; Lieberherr et al. 2003; Sappl et al. 2004; Uquillas et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005; Langlois-Meurinne et al. 2005). Besides activating stress defenses, SA is known to inhibit JA-and auxin-mediated responses, as part of the SA-mediated disease-resistance mechanism (Fujita et al. 2006; Ndamukong et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007).

The aim of this study was to expand our knowledge about SA function in defense, identifying the subset of SAIGs that mediate early defense responses to SA in Arabidopsis seedlings (early SAIGs). For this purpose, we studied the expression profiles of wild type and npr1-1 mutant Arabidopsis seedlings in response to short SA treatments, with the Complete Arabidopsis Transcriptome MicroArray (CATMAv2) chip. We identified 217 early SAIGs and found that a small proportion of them (24 genes) used an NPR1-independent pathway. Analysis of the functional categories of these genes indicates that NPR1-independent SAIGs mainly code for proteins involved in stress defense responses and C-compound metabolism, while proteins involved in protein phosphorylation and response to biotic stress were over-represented in the group of NPR1-dependent SAIGs. We confirmed, for a selection of these genes, that they are also responsive to inoculation with the avirulent bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato AvrRpm1.

In silico promoter analysis of the early SAIGs identified in this study, and expression analysis performed for a selection of these genes (coding for glutaredoxins GRXC9 and GRXS13; the ANAC102 transcription factor, the unclassified SDRLP protein, a lectin like protein LLP and the NPR1-interactor NIMIN1), indicates that SA activates the transcription of theses genes by a mechanism involving the subclass II of TGA transcription factors (TGA 2/5/6). Based on present findings and on previously published work, we propose a model to explain how a proper combination of SA-responsive promoter elements (as-1-like, TL-1 and TGA boxes), transcriptional regulators and co-regulators (TGA factors, NPR1 and other uncharacterized factors) could mediate the temporal control of early SAIGs expression.

Materials and methods

Plant growth conditions and treatments

The Arabidopsis thaliana wild-type, npr1-1 mutant (Cao et al. 1994) and tga6-1 tga2-1 tga5-1 triple mutant (Zhang et al. 2003) plants used in this study were from Columbia (Col-0) ecotype. Plants were grown in vitro in MS medium containing 15 g/l sucrose, under controlled conditions in a growth chamber (16 h light, 60 μmoles m−2 s−1, 22 ± 2°C). Experiments were performed in 15 day-old seedlings (collected at 9:00 am) carefully taken from the MS medium and placed, root side down, in a Petri dish containing the corresponding solutions. For SA treatment, seedlings (wt and npr1-1 mutant) were incubated in a 0.5 mM SA solution in MS medium, under continuous light (60 μmoles m−2 s−1) for 2.5 h in the case of microarray analysis, or for 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 8, 12 and 24 h for Northern blot analysis. Stock solution of 1 M SA (Sigma) was fresh-prepared in water. Control samples were incubated under the same conditions in MS medium.

To evaluate the need of de novo protein synthesis for SA-induced response, the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) was used. Seedlings were pre-incubated for 1 h in MS medium in the absence (control) or presence of 20 μg/ml CHX and then exposed to 0.5 mM SA or MS for 2.5, 8 and 24 h. Stock solution of 20 mg/ml CHX (Sigma) was fresh-prepared in water. To evaluate transcript stability, seedlings were first incubated with 0.5 mM SA (prepared in MS) for 2 h and then transferred to MS medium (controls) or to a 0.5 mM SA solution, either in the presence or absence of 0.6 mM cordycepin (Sigma). A control sample treated with MS for 2 h was included. Samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 5 and 8 h.; whole seedlings were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until RNA purification.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from control and SA-treated seedlings of wild type and npr1-1 mutant plants (pool of 20 seedlings for replicate, two independent biological replicates for each treatment) with Trizol®, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). In each case, we compared SA-treated seedlings with that from control-treated seedlings on an Arabidopsis cDNA microarray, CATMAv2. Each comparison was repeated in dye-swap leading to 4 hybridizations per comparison.

The CATMAv2 array used in this study was an updated version of CATMAv1 array that was previously described and validated (Hilson et al. 2004; Allemeersch et al. 2005). This array consisted of 23,520 features, including 18,981 unique GSTs, 768 positive/negative controls (Amersham BioSciences), and 243 blanks, printed on Type VIIstar reflective slides (Amersham BioSciences) using a Lucidea Array spotter (Amersham BioSciences). The annotation of the clone set can be accessed via the ArrayExpress database as accession number A-MEXP-10 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) or via the VIB MicroArray Facility Web site (http://www.microarrays. be). Prior to hybridization, the slides were washed in 2× saline-sodium phosphate-EDTA buffer, 0.2% SDS for 30 min at 25°C. RNA was amplified using a modified protocol of in vitro transcription (Puskas et al. 2002). Briefly, 5 mg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to double-stranded cDNA using an anchored oligo(dT) 1 T7 promoter [5′-GGCCAGTGAATTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGCGGT24(ACG)-3′ (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium)]. From this cDNA, RNA was produced via T7-in vitro transcriptase until an average yield of 10–30 mg of amplified RNA. The amplified RNA (5 mg) was labeled with dCTP-Cy3 or Cy5 (Amersham BioSciences) by reverse transcription using random nonamer primers (Genset, Paris). The resulting probes were purified with Qiaquick (Qiagen) and analyzed for amplification yield and incorporation efficiency by measuring the DNA concentration at 280 nm, Cy3 incorporation at 550 nm, and Cy5 incorporation at 650 nm using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Rockland, DE). A good target had a labeling efficiency of 1 fluorochrome every 30–80 bases. For each target, 40 pmol of incorporated Cy5 or Cy3 were mixed in 210 ml of hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 1× hybridization buffer (Amersham BioSciences), 0.1% SDS. Each spike mix was hybridized against the reference RNA (spikes at 100 cpc) and repeated with dye swap to make up 14 hybridizations in total. Hybridization and post hybridization washing were performed at 45°C with an Automated Slide Processor (Amersham BioSciences). Post-hybridization washing was done in 1× sodium chloride/sodium citrate buffer (SSC), 0.1% SDS, followed by 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS and 0.1× SSC. Arrays were scanned at 532 nm and 635 nm using a Generation III scanner (Amersham BioSciences). Images were analyzed with ArrayVision (Imaging Research, St. Catharines, Canada). All protocols are available at the VIB MicroArray FacilityWeb site (http://www.microarrays.be) and at ArrayExpress under accession numbers P-MEXP-578, P-MEXP-579, P-MEXP-581, P-MEXP-582 for Cy3 labeling, Cy5 labeling, hybridization, and scanning, respectively.

Microarray data analysis

Spot intensities were measured as artifact removed total intensities, subtracted with the local background (sARVol), and filtered based on two standard deviations above background. For each gene, ratios of red (Cy-5) over green (Cy-3) intensities (I) were calculated and normalized via a Lowess Fit of the log2 ratios [log2(Icy-5/Icy-3)] over the log2 total intensity [log2(Icy-5*Icy-3)]. Genes were considered differentially expressed if the normalized ratios were statistically significant using a two-tailed t test (P < 0.01) between the biological and dye-swap repeats and were higher or equal to two-fold.

Functional classification of genes was performed according to the Functional Catalogue (FunCat) version 2.1 available at http://mips.gsf.de/proj/funcatDB (Ruepp et al. 2004). Over-represented functional categories in the two lists of early SAIGs compared to the complete Arabidopsis genome were obtained according to the MIPS classification using BioMaps tool from the VirtualPlant webpage (http://virtualplant.bio.nyu.edu). Hypergeometric method and Bonferroni correction were used for the analysis with a P value cutoff of 0.05. To collect expression data of selected genes in response to stress, the stimulus analysis tool from the public GeneVestigator V3 database, which compile information of Affymetrix GeneChip experiments, was used (https://www.genevestigator.ethz.ch/; (Laule et al. 2006). Intersection analysis tool from VirtualPlant version 0.9 (http://virtualplant-prod.bio.nyu.edu/cgi-bin/virtualplant.cgi) was used to analyze the intersections between different lists of genes from microarray experiments.

Northern analysis

For Northern blot analysis, 10 μg total RNA (isolated by using Trizol®) of the different samples were separated on formaldehyde-agarose gels, as previously described (Blanco et al. 2005). Radioactive signals were either quantified by a Phosphorimager (Cyclone, Storage Phosphor screen, Packard Bioscience Company) or detected by autoradiography after 12 h exposure. Gene-specific DNA probes were obtained by PCR using cDNA from SA-treated seedlings as template and specific primers designed according to each gene sequence. Amplified probes were cloned and sequenced. Sequences of the gene specific primers are described in Table 1. Probes were labeled by PCR as described (Blanco et al. 2005).

Plant inoculation with P. syringae

For bacterial inoculation assays, 6-week old plants grown on soil under controlled condition in a growth chamber (22 ± 2°C, 10 h light, 100 μmoles m−2 s−1) were inoculated with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000 that expresses the AvrRpm1 gene (Pst/AvrRpm1). A bacterial suspension of 5 × 106 cfu/ml in 10 mM MgCl2 was infiltrated on the abaxial side of the leaves with a 1 ml syringe (Pavet et al. 2006). Mock-treated plants were infiltrated with 10 mM MgCl2. Bacteria- and mock-infiltrated leaf samples were collected at 0, 5, 21, 26 and 48 h post infiltration, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until RNA purification or SA quantification.

Quantification of SA

Free and conjugated SA extracted from leaf tissues was quantified by HPLC as described (Verberne et al. 2002).

Promoter analysis

Over-represented promoter elements were independently searched in the groups of 31 NPR1-independent and 197 NPR1-dependent SAIGs, using the Motif-Sampler software (http://www.esat.kuleuven.ac.be/~thijs/Work/MotifSampler.html) (Thijs et al. 2002). For each group of genes, 1 kb of the genomic sequence upstream from the inferred translational start site was downloaded from TAIR database (The Arabidopsis Information Resource, http://www.arabidopsis.org). Promoters analysis was performed essentially as described (Blanco et al. 2005), except that the motif lengths (w) were set at 16 and 20 bp. For each search, the algorithm was iterated 2,000 times; independent outputs were merged and the 10 highest scored motifs were selected and ranked according to their log-likelihood scores. Finally, to search for known plant promoter elements that matched the selected motifs, PLACE database (Database of Plant Cis-acting Regulatory DNA elements, http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/) was used (Higo et al. 1999).

Results

Identification of early SA-induced genes, determination of NPR1 dependence and functional classification

To analyze the early genetic response of Arabidopsis to SA, transcript profiles of seedlings incubated for 2.5 h with or without SA were compared using CATMAv2 (Complete Arabidopsis Transcriptome MicroArray) DNA chips including 18,981 unique gene specific tags (GSTs) (Lurin et al. 2004). The requirement of NPR1 for this response to SA was determined comparing transcript profiles of wild type and npr1-1 mutant seedlings. Genes differentially activated by SA were selected according to the results of a t-test analysis using a two-fold increase in expression as threshold. We selected 217 SAIGs (1.1% of total genes monitored) from wild type plants and 34 SAIGs (0.18%) from npr1-1 mutant plants (see supplementary Table S1). Genes whose steady-state mRNA levels increased in response to SA exclusively in the wild type plants, were considered as “early NPR1-dependent SAIGs” (193 genes), while genes whose mRNA levels increased after SA treatment in both wild type and npr1-1 plants were considered as “early NPR1-independent SAIGs” (24 genes). Genes that showed reduced responsiveness to SA in the npr1-1 background compared with the wild type were included in the early NPR1-independent SAIGs.

In a previous study, we identified 14 early SAIGs (Uquillas et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005). In the CATMAv2 chip, only 6 of these genes were represented by probes and, although 5 of them seemed to be induced by SA, the induction values were statistically significant for only 3 of these genes (At2g29420, At5g54610, At3g11280). These 3 genes were included in the list of 217 SAIGs. Therefore, for further classification and expression analysis of early SAIGs, we considered the 217 genes identified in this study and the 11 SAIGs (4 NPR1-dependent and 7 NPR1-independent) that were identified and corroborated previously (Uquillas et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005). The list of early NPR1-dependent SAIGs with activation levels higher than 3 (46 out of 197 genes) is shown in Table 2, whereas the list of the 31 early NPR1-independent SAIGs is shown in Table 3.

Early NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent SAIGs were classified in functional categories according to the Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences classification (MIPS) (Ruepp et al. 2004), using the FunCat database. Over-represented MIPS categories were identified by using the BioMaps tool from Virtual Plant database (http://virtualplant.bio.nyu.edu). Different sets of functional categories were overrepresented in NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent SAIGs (Table 4). In the group of 197 early NPR1-dependent SAIGs, the categories “Metabolism” and “Protein Fate” (represented by subcategories “phosphate metabolism” and “protein modification by phosphorylation”) and the categories “Cell rescue, Defense and Virulence”/“Interaction with the environment”/“Cell fate” (subcategories associated to defense responses to pathogens) were overrepresented (Table 4). Accordingly, the functional groups mainly represented in this class of SAIGs were protein kinases (36 genes), disease resistance proteins (11 genes) and WRKY transcription factors (7 genes) (see Table 2 and supplementary Table S1).

On the other hand, the over-represented categories in the 31 early NPR1-independent SAIGs were “Metabolism” (subcategory “C-compound and carbohydrate metabolism”) and “Cell Rescue, Defense and Virulence”/“Interaction with the environment” (subcategories associated to detoxification and response to chemicals and hormones) (Table 4). Consistently, 6 genes coding for UGTs and 4 genes coding for glutaredoxins and GSTs were identified in this class of SAIGs (Table 3).

To get a preliminary idea if the SAIGs identified in this study play a role in defense responses against different stressful stimuli, we analyzed the available transcriptomic expression data for these genes using GeneVestigator (http://www.genevestigator.ethz.ch/) (Laule et al. 2006). We did an independent search of the expression data for the list of early NPR1-dependent SAIGs that displayed an increase of more than 3 times in their steady-state mRNA levels in response to SA (listed in Table 2) and for the list of early NPR1-independent SAIGs (listed in Table 3). Early NPR1-independent SAIGs were more responsive than early NPR1-dependent SAIGs to a wide range of stress treatments (biotic, chemical and abiotic) that alter the redox cell homeostasis (Fig. 1). For example, early NPR1-independent SAIGs—in contrast to early NPR1-dependent SAIGs—were responsive to inoculation with Botrytis cinerea and to treatments with several chemical stressors (Fig. 1). In addition, this study showed that both groups of genes were responsive to SA but not to other hormones involved in stress (data not shown).

Expression profiles of SAIGs obtained from public microarray database. The expression profiles of the NPR1-dependent SAIGs whose induction was >3-fold (see Table 2) and of all NPR1-independent SAIGs identified in this study (see Table 3) were analyzed on microarray experiments selected from the GeneVestigator database (Laule et al. 2006). Experiments with other stress treatments, either hormonal (ABA, ACC, ethylene, GA3, IAA), biotic or abiotic, in which SAIGs showed no response were not included. Expression levels (log2 ratio) are indicated by a color code shown at the bottom of the figure. The number of arrays used in each experiment is indicated at the right side. Genes with highest induction level in each group are marked with a green box (AT1G28480 for NPR1-independent and AT5G03350 for NPR1-dependent group)

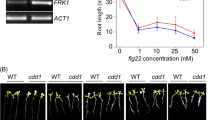

With the double purpose of corroborating the results of the microarray experiment regarding the responsiveness to SA and the requirement of NPR1 coactivator observed in, and analyzing the kinetics of this process, we selected a group of representative genes according to the level of transcript accumulation by SA and to their function. Among the chosen genes were 5 early NPR1-dependent SAIGs (LLP, NIMIN1, NIMIN2, WRKY38, UGT76B1) and 5 early NPR1-independent SAIGs (GRXC9, GRXS13, F3′H, ANAC102, SDRLP) with high levels of transcript accumulation and representative of different functional categories (Tables 2, 3). OPR1 and PR-1 were used as controls for NPR1 independence and dependence, respectively (Blanco et al. 2005). The experiment involved treatment of wild type and npr1-1 mutant Arabidopsis seedlings with SA for different periods of time, and Northern blot analysis of transcripts levels (Fig. 2). As expected, all genes selected were activated by SA in wild type seedlings. We also confirmed that SA-induced activation of WRKY38, UGT76B1, NIMIN1, NIMIN2, LLP genes did not occur in the npr1-1 mutant, while activation by SA of SDRLP, ANAC102, GRXC9, GRXS13 and F3′H was detected in both genotypes (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the kinetic behavior of these genes after activation by SA was different and correlated with the degree of requirement of NPR1 for activation. Complete independence of NPR1 for SA-induced activation correlated with an earlier and transient activation by SA (SDRLP, ANAC102 and OPR1 in Fig. 2). As previously reported (Blanco et al. 2005), we found that activation of early NPR1-independent SAIGs by SA in the npr1-1 mutant had a more sustained activation (Fig. 2), which correlated with higher accumulation of SA (data not shown). Genes with partial requirement of NPR1 showed an early but more sustained activation by SA (GRXC9, GRXS13, F3′H in Fig. 2). Consistent with our microarray data (Table 3), activation of these genes was detected in the npr1-1 mutant but a functional NPR1 was required for maximum activation rate.

Time-course of SA-induced expression of selected SAIGs in wild type and npr1-1 plants. RNA was isolated from 15 day-old plants either treated with 0.5 mM SA (SA) or maintained in MS medium (C) for the times (hours) indicated at the top of the figure. Ten micrograms of total RNA were loaded per lane, and the blots were hybridized with specific probes for the following genes: SDRLP (AT4G13180), ANAC102 (AT5G63790), GRXC9 (AT1G28480), GRXS13 (AT1G03850), F3′H (AT5G24530), WRKY38 (AT5G22570), UGT76B1 (AT3G11340), NIMIN-1 (AT1G02450), NIMIN-2 (AT3G25882) and LLP (AT5G03350). OPR1 (AT1G76680) and PR1 (AT2G14610) were used as controls for NPR1 independence and dependence, respectively. ACTIN 3 (AT3G53750) was used as a loading control

All genes classified as early NPR1-independent SAIGs had a peak of increase in mRNA levels around 1–2.5 h after SA treatment. In contrast, early NPR1-dependent SAIGs (WRKY38, UGT76B1, NIMIN1, NIMIN2, LLP in Fig. 2) displayed a more delayed kinetics (peak of mRNA levels after 5 h). The activation kinetics of both classes of early SAIGs was clearly distinguishable from that of PR-1 gene, a marker for “late NPR1-dependent SAIGs” (Fig. 2).

SA-mediated activation of selected SAIGs

To study the mechanism of SA-induced activation we selected six SAIGs: two completely independent of NPR1 (ANAC102 and SDRLP), two genes partially dependent on this coactivator (GRXC9 and GRXS13) and two completely dependent on NPR1 for activation (NIMIN1 and LLP).

In the first place, we determined if activation of these genes required de novo protein synthesis. Wild-type seedlings were pretreated for 1 h with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) (or MS as a control), and then treated for 2.5, 8 or 24 h with SA (or MS as a control). After this, the steady state levels of transcripts were determined by Northern blot. Activation of SDRLP, ANAC102, GRXS13, GRXC9 and NIMIN1 genes by SA was not inhibited by CHX (Fig. 3a). Therefore, SA increases the mRNA levels of these genes by a mechanism independent of de novo protein synthesis and likely controlled by modification of pre-existing factors. Interestingly, the genes ANAC102 and GRXC9 were strongly activated by CHX in the absence of SA (Fig. 3a). This behavior was previously reported by us and others in early SAIGs of Arabidopsis and tobacco (Qin et al. 1994; Horvath et al. 1998; Uquillas et al. 2004). As judged by information from public microarray database, it seems to be a common response of a large number of early SAIGs (see response to CHX in Fig. 1). A possible explanation for this effect is that one of the mechanisms that controls transcription of these early SAIGs is basal repression by a labile protein, whose effect can be relieved by SA (see model in Fig. 6). In the case of LLP, pretreatment with CHX partially inhibited the activation by SA. This is compatible with a mixed activation mechanism. In contrast, we found that SA-mediated activation of PR-1, a marker for late genes, was completely inhibited by CHX, as previously reported (Qin et al. 1994).

Analysis of SA-induction mechanism for 6 selected SAIGs. a Effect of the inhibitor of protein synthesis, cycloheximide (CHX) on SAIGs expression. 15 day-old wild type seedlings were pretreated for 1 h with CHX (six lines on the right side) or MS (control, six lines on the left sides) and then incubated for 2.5, 8 or 24 h with 0.5 mM SA or MS as a control (C), either in the presence or absence of CHX. Ten μg of total RNA were loaded per lane, and the blots were hybridized with specific probes for the genes indicated in the figure. PR1 and 18S rRNA genes were used as controls for CHX treatment and loading, respectively. b Effect of the transcriptional inhibitor cordycepin on SAIGs expression. 15 days-old wild type seedlings were pretreated with 0.5 mM SA or MS as a control (C) for 2 h. Then, seedlings were transferred to MS or 0.5 mM SA in the absence (left panel) or presence of 0.6 mM cordycepin (right panel) for the times (hours) indicated at the top of the figure. RNA was analyzed as described above. NIA2 (AT1G37130) and ACTIN 3 (AT3G53750) were used as controls of cordycepin effect and loading, respectively

To determine if the early increases of mRNA levels of selected SAIGs caused by SA result from mRNA stabilization or from transcriptional activation, we analyzed the expression of these genes in the presence of cordycepin, a transcriptional inhibitor (Gutierrez et al. 2002). Wild type seedlings were treated with SA for 2.5 h to produce the maximum transcript accumulation, and then incubated for different periods of time with SA or MS medium (control) in the presence or absence of cordycepin (0.6 mM). The mRNAs were detected by Northern blot analysis and quantified by a Phosphorimager. The effect of cordycepin was controlled by analyzing the levels of NIA2 mRNA (nitrate reductase 2), a constitutively expressed gene not responsive to SA. In the absence of cordycepin, removal of SA produced a decay of mRNA levels for all SA-responsive genes (Fig. 3b, compare C vs. SA in left panels). When transcription was inhibited by cordycepin, a similar decay of mRNA levels was detected in the absence or in the presence of SA for all genes analyzed (Fig. 3b, compare C vs. SA in right panels). To support this conclusion, we also calculated mRNA half-lives (t1/2) for all genes analyzed, in the absence and in the presence of SA, using three independent biological samples. For this, we quantified mRNA levels by Phosphorimager and the t1/2 values were calculated according to Lidder et al. (2005). Results from this analysis indicate that SA does not affect t1/2 of SAIGs mRNAs (data not shown). These results are consistent with the idea that SA does not increase mRNA levels of early SAIGs through increasing mRNA stability, and support the idea that SA induces gene activation by exerting a transcriptional control.

We then determined whether the subclass II of TGA transcription factors (TGA2, TGA5 and TGA6) was involved in the transcriptional activation or de-repression of these early genes by SA. For this purpose, we compared the response of selected genes to SA treatment in wild type and tga2-1/tga5-1/tga6-1 triple mutant Arabidopsis seedlings (Zhang et al. 2003). As shown in Fig. 4, activation of the early NPR1-independent (SDRLP, ANAC102, GRXC9 and GRXS13) and the early NPR1-dependent (LLP and NIMIN1) SAIGs was severely impaired in the tga2-1/tga5-1/tga6-1 triple mutant, indicating involvement of TGA2/5/6 in the transcriptional activation of these genes. In contrast, an increase in basal levels and impairment of SA-activation at 8, but not at 24 h post treatment, was detected for PR-1 gene in the tga2-1/tga5-1/tga6-1 triple mutant (Fig. 4). This behavior is consistent with the possibility that the TGA2/5/6 factors are involved in both the basal repression and the SA-mediated activation of PR-1 (Zhang et al. 2003; Rochon et al. 2006), but it also suggests the involvement of other factors in late activation of PR-1 by SA (Wang et al. 2005).

SA-induced expression of selected SAIGs in tga6-1/tga2-1/tga5-1 plants. RNA was isolated from 15 day-old plants either treated with 0.5 mM SA (SA) or maintained in MS medium (c) for the times (hours) indicated at the top of the figure. Ten micrograms of total RNA were loaded per lane, and the blots were hybridized with specific probes for the indicated genes. ACTIN 3 was used as a loading control

SA-induced genes revealed common cis-elements in their promoters

Having found that the SAIGs selected in this study were transcriptionally activated by SA through a TGA-dependent mechanism, we looked for common putative cis-elements in the promoter sequences of both groups of SAIGs. We searched for over-represented motifs (16 and 20 bp length) separately in the 31 early NPR1-independent SAIGs (Table 3) and in the 197 early NPR1-dependent SAIGs (supplementary Table S1), with the software MotifSampler (Thijs et al. 2002). Over-represented motifs were ranked according to their log-likelihood score, which considers the conservation of the motifs and the number of copies of each motif found in the input sequences. Table 5 shows the 10 best-ranked motifs for each group of genes. To determine if the motifs found in this study correspond to defined regulatory elements already described in plant promoters, we searched for these motifs in PLACE and TRANSFAC databases (Wingender et al. 1996; Higo et al. 1999). Interestingly, the 10 best ranked 20 bp motifs found in the early NPR1-independent SAIGs, matched the as-1-like element described in the 35S promoter of the cauliflower mosaic virus (Qin et al. 1994). This is in agreement with results we described before for a smaller group of early NPR1-independent SAIGs (Blanco et al. 2005). On the other hand, for early NPR1-dependent SAIGs, the 10 best ranked 16 bp motifs found matched the core of TL-1 element (Table 5). This element was recently described as a consensus sequence over-represented in the promoter of a group of 13 NPR1-responsive ER-resident genes (Wang et al. 2005).

Early SAIGs are activated in the defense reaction triggered by an avirulent bacterium

Arabidopsis plants activate SA biosynthesis as part of their defense reaction to the attack of avirulent pathogens (Summermatter et al. 1995). We wanted to know whether the expression of the early SAIGs identified here increased during the activation of pathogen-induced defenses. For this purpose, we inoculated Arabidopsis plants with the avirulent pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 that carries the AvrRpm1 gene (Pst AvrRpm1, 5 × 106 cfu/ml); control plants were mock inoculated. RNA samples were obtained at 0, 5, 21 and 48 h post inoculation (hpi) and transcript levels of the early SAIGs were detected by Northern blot. As shown in Fig. 5a, activation of all SAIGs analyzed (SDRLP, ANAC102, GRXS13, GRXC9, NIMIN1 and LLP) was detected starting 5 h post infection (hpi). SA levels were measured by HPLC in pathogen-treated samples collected at 5, 26 and 48 hpi. Increase in SA levels was detected from 5 hpi (Fig. 5b). All genes, except GRXS13, showed a peak of activation earlier than PR-1. These results support a role for SAIGs in the defense response to pathogen infection.

Expression of SAIGs and SA levels in Arabidopsis plants inoculated with Pseudomonas. Six week-old plants were inoculated with Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 carrying the AvrRpm1 gene (Pst AvrRpm1, 5 × 106 cfu/ml) or with MgCl2 (mock). Then, leaf samples were collected at the indicated times for RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis (a), and for measurement of SA levels by HPLC (b). SAG, glycosilated-SA. Averages and standard deviations of SA and SAG levels were calculated from three independent biological replicates

Discussion

It has been clearly established that the rise of SA levels and the subsequent induction of genes triggered by this hormone (SAIGs) are essential steps for the development of a defense reaction to pathogen infection (SAR), and to other stressful environmental conditions (Durrant and Dong 2004; Loake and Grant 2007). Although important knowledge concerning SA effects has been obtained in the last years, essential elements of its action in the cellular response to stress are still unknown (Loake and Grant 2007). Looking for clues to understand SA role in defense to stress, we have focused our attention in the early responses triggered by this hormone. We previously described two pathways for rapid activation of SAIGs; one dependent on the NPR1 coactivator and other independent of it (Uquillas et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005; Holuigue et al. 2007).

The transcriptomic and expression analyses described in this article further support the existence of these two pathways for rapid activation of SAIGs; one independent of NPR1 used by 14% of these genes, and the other dependent of NPR1 used by the rest of them. Here we report that these two groups of genes, not only differ in their main functional categories, but also in their timing and mechanism of activation by SA. Considering this and previous published work (Niggeweg et al. 2000; Pontier et al. 2001; Uquillas et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005; Thurow et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2005, 2006; Butterbrodt et al. 2006; Rochon et al. 2006) we propose a model to explain the differences in the SA-mediated activation of these two classes of early SAIGs (Fig. 6).

Mechanistic model for SA-mediated early activation of genes. a Temporal course of the reaction after SA addition is indicated by the color bar at the top of the figure. Windows corresponding to peaks of induction of two classes of early SAIGs are indicated. “Early NPR1-independent SAIGs” are rapidly and transiently activated by SA by reversible recruitment of a coactivator (CoA) to the TGA2/as-1-like element (T2/as-1) complex. Putative inhibitors (I) that recognize CoA and/or TGA2 could be involved. b “Early NPR1-dependent SAIGs” are activated by SA via recruitment of activated NPR1 (NPR1A) to form the transcriptionally active NPR1A-T2-TGA ternary complex. We also propose involvement of a putative transcriptional activator (TL-1-A) that recognizes the TL-1 element. as-1-like element: two TGACGTCA-like motifs spaced by 4 nucleotides; TGA box: TGACG; TL-1 box: TTCTTCTTC. Red arrows represent activation and blocked red arrows represent repression

Role of early SAIGs in the stress defense response

Several functions in the defense response to stress have been attributed to the different classes of SAIGs. An antimicrobial role has been reported for PR genes, the well known group of genes belonging to the class of late NPR1-dependent SAIGs (Maleck et al. 2000; van Loon et al. 2006). SAIGs recently identified as primary targets of NPR1, which can be classified as early NPR1-dependent SAIGs, code for proteins from the protein secretory machinery and WRKY factors (Wang et al. 2005, 2006). The identification of early SAIGs (NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent pathways) described in this work supports the idea that SA plays additional roles in defense and acclimatory responses to stress, such as recovery of the cell redox balance, intracellular stress signaling, improvement of pathogen recognition, and promotion of metabolic changes. Based on the expression analysis of a selection of these genes in response to an avirulent bacterial pathogen, we propose that early SAIGs may contribute to generate a pathogen-induced defense reaction. Intersection of our list of 228 early SAIGs with the list of 1,187 genes activated after 8 h of treatment with BTH (Wang et al. 2006), indicates that 88 out of the 228 genes (38%) had not been previously considered as BTH-dependent SAIGs. A considerable proportion of the genes identified here (133 genes, 58%) were also detected as ozone-responsive genes (Mahalingam et al. 2005), indicating that early SAIGs also play a role in the response to ozone treatment. We will focus our discussion in some of the functions early activated by SA, which could be more relevant to the role of this hormone in defense and acclimatory responses.

The regulation of changes in the cellular redox status is one of the roles recently attributed to SA in pathogen-induced defenses and light acclimatory responses in Arabidopsis (Durrant and Dong 2004; Fobert and Despres 2005; Foyer and Noctor 2005; Mateo et al. 2006; Holuigue et al. 2007). This regulatory role seems relevant to SA function, considering that this hormone is also produced and required for defense responses to different stressful conditions associated to cellular oxidative stress, such as UV irradiation, ozone exposure and high light (Yalpani et al. 1994; Surplus et al. 1998; Rao and Davis 1999; Mateo et al. 2006; Janda et al. 2007). A pro-oxidative activity of SA recognized more than 15 years ago (Chen et al. 1993) gives support to the positive feedback interaction between SA and reactive oxygen species (ROS) associated to cell death (Shirasu et al. 1997; Overmyer et al. 2003; Dat et al. 2007). Nevertheless, evidences of an antioxidant activity of SA associated to defense and acclimation processes have appeared only in the last years (Despres et al. 2003; Mou et al. 2003; Yang et al. 2004; Mateo et al. 2006; Tada et al. 2008). The molecular basis for this antioxidant activity is still unknown.

Results reported here support an antioxidant role for SA and strengthen previous evidences showing that SA triggers rapid activation of genes with antioxidant and detoxifying activities, through an NPR1-independent pathway (Uquillas et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005; Holuigue et al. 2007). Interestingly, in this class of early NPR1-independent SAIGs we detected genes coding for two glutaredoxins (GRXC9 and GRXS13), two glutathione S-transferases (AtGSTU7 and AtGSTF8) and 6 UDP-glycosyl transferase (UGT72B1, UGT75B1, UGT75D1, UGT74F2, UGT73B2, UGT73B1) (Table 3).

GRXs, together with thioredoxins (TRX), are the two major enzymatic systems that catalyze reversible thiol-based reduction of target proteins (Rouhier et al. 2008). These proteins have been allegedly implicated in the SA-dependent reduction of NPR1 and TGA factors required for the transcription of defense genes (Fobert and Despres 2005; Foyer and Noctor 2005; Tada et al. 2008). The glutaredoxin GRXC9 (coded by At1g28480, also named GRX480) was recently reported to be induced by SA and to interact with TGA factors (Ndamukong et al. 2007). Ectopic expression of GRXC9 suppresses JA-responsive PDF1.2 transcription, suggesting that this enzyme could be a key piece in the SA/JA cross-talk (Ndamukong et al. 2007). Here we report that GRXC9 gene is rapidly activated by SA (peak 1–2.5 h, see Fig. 2), and by infection with an avirulent pathogen (Fig. 5). We also found that activation of GRXC9 by SA is partially dependent on NPR1 function, because considerable levels of GRXC9 mRNA were detected in the npr1.1 mutant compared to the wild type (50% at 2.5 h, Fig. 2). In contrast, Ndamukong et al. reported that activation of GRXC9 by SA is almost negligent in the npr1.1 background (Ndamukong et al. 2007). These differences could be due to differences in the experimental conditions used in both experiments; we used 15 days-old seedlings treated with 0.5 mM SA, while Ndamukong et al. used 3 week-old plants treated with 1 mM SA.

The other glutaredoxin gene (GRXS13, At1g03850), which is also included in the group of early NPR1-independent SAIGs, codes for an enzyme whose function in defense has not been studied. Here we show that SA activates GRXS13 with an early and sustained kinetics (Fig. 2). Similarly, a strong and sustained activation of this gene was also detected after pathogen infection (Fig. 5). As with GRXC9, we included GRXS13 in the list of early NPR1-independent SAIGs, due to the considerable levels of activation by SA detected in the npr1-1 mutant (Fig. 2).

We found that SA also produces a rapid activation of two GSTs and six UGTs, by an NPR1-independent pathway. These transferases catalyze the formation of S-glutathionylated and O-glycosylated conjugates of different acceptor molecules. As we previously discussed (Blanco et al. 2005; Holuigue et al. 2007), these enzymes have been implicated in the detoxification of endogenous and xenobiotic compounds, being good candidates to diminish toxic effects of metabolites (including ROS) in the stress defense reaction (Lim and Bowles 2004; Edwards et al. 2005).

In sum, a rapid induction of this group of 10 enzymes (GRXs, GSTs and UGTs) following the rise in SA levels during the pathogen-induced defense reaction could contribute to recover the cellular redox balance and to generate the reducing environment for NPR1/TGA reduction required for the activation of late SAIGs responsible for stress resistance (Despres et al. 2003; Mou et al. 2003).

This study indicates additional functions of the rapid cellular response triggered by SA. A role for SA in improving pathogen recognition and signaling for defense response is also suggested by the identification of genes coding for 11 disease resistance (R) proteins, 36 protein kinases and 28 proteins with protein binding functions among the early SAIGs. Activation of genes coding for transcription factors belonging to different families (8 WRKY, 4 NAM, 3 ERF/AP2 and 2 myb) is also part of the rapid response triggered by SA. Only two of these genes are activated by an NPR1-independent pathway, ANAC102 (NAM family) and WRKY 75. Here we show that ANAC102 is rapidly activated by SA (Fig. 2) and also by treatment with an avirulent pathogen (Fig. 5). Although ANAC102 has not been previously characterized, is highly homologous to ATAF2, previously described as a repressor of PR genes in Arabidopsis (Delessert et al. 2005). WRKY75, together with the NPR1-dependent WRKY 46, are the only WRKYs detected here as early SAIGs, that have not been previously associated to pathogen-induced defense responses (Eulgem and Somssich 2007). WRKY75 has been reported to be involved in H2O2-induced cell death and as a modulator of phosphate acquisition and root development (Gechev et al. 2005; Devaiah et al. 2007). The function of ANAC102 and WRKY75 in the defense reaction in Arabidopsis remains to be characterized.

Mechanisms for defense genes activation triggered by SA

The results of the genome-wide analysis reported here give further support to the existence of different mechanisms responsible for the rapid activation of SAIGs. Based on the study of representative members of the SAIGs identified in this work, we propose that SA-mediated gene activation involves transcriptional activation and/or de-repression. The mechanisms involved differ in their requirement for NPR1, TGA factors and SA-responsive promoter elements. Based on this and on previous mechanistic studies, we propose an explanatory model for the SA-induced activation of the two classes of early SAIGs that takes place at different times after exposure to SA (Fig. 6).

A cluster of 31 genes corresponding to the class of early NPR1-independent SAIGs, activated by SA after 0.5–2.5 h of treatment, has been identified in this (Table 3) and previous work from our group (Uquillas et al. 2004; Blanco et al. 2005). We propose that early transcriptional activation of these genes by SA is controlled by the as-1-like element (TGACGTCAnnnnTGACGTCA) that is over-represented in the group of 31 promoters (Table 5). As we previously discussed (Blanco et al. 2005), as-1 is structurally and functionally different from isolated TGA boxes (TGACG) found in PR-1 promoter (Krawczyk et al. 2002; Butterbrodt et al. 2006). as-1 element confers immediate early responsiveness to SA (Qin et al. 1994) by a mechanism involving oxidative signals (Garreton et al. 2002). We think that binding of a member of the subclass II of TGA factors (TGA2/5/6) to the as-1-like element is required for activation of these genes by SA. This is supported by our evidence that activation of SDRLP, ANAC102, GRXC9, and GRXS13 (representative early NPR1-independent SAIGs) in Arabidopsis is severely impaired in the tga2-1/tga5-1/tga6-1 triple mutant (Fig. 4). Similarly, evidence obtained in tobacco indicates that TGA2.2, member of the subclass II of TGA factors in this species, is the main component of the as-1 binding activity in nuclear extracts (Niggeweg et al. 2000) and is essential for activation of a couple of tobacco early genes (Pontier et al. 2001; Thurow et al. 2005). The question that remains open is how SA activates transcription of early NPR1-independent SAIGs mediated by TGA2/5/6-as-1 interaction. One possibility is that SA activates binding of TGA2/5/6 to the as-1 element. This possibility has been explored in tobacco with contradictory results (Jupin and Chua 1996; Stange et al. 1997; Garreton et al. 2002; Butterbrodt et al. 2006). Furthermore, it must be mentioned that neither TGA2 from Arabidopsis (Rochon et al. 2006) nor TGA2.2 from tobacco (Thurow et al. 2005) have transactivation activity. Therefore, other protein(s) must provide the transactivation domain to the TGA2/5/6-as-1 complex. In sum, as shown in Fig. 6, we propose that SA activates early NPR1-independent SAIGs by recruitment of a co-activator protein (CoA) to the TGA2-as-1 complex already formed under basal conditions. The presence of an inhibitor, which sequesters the coactivator or blocks the TGA2-as-1 complex under basal conditions has been previously proposed in tobacco (Johnson et al. 2001; Butterbrodt et al. 2006) and is consistent with the activation induced by CHX found in some of the early genes (Fig. 1 and (Uquillas et al. 2004).

Genes belonging to the class of early NPR1-dependent SAIGs have been identified in this (Table 2 and supplementary Table S1) and in previous studies oriented to identifying primary targets of NPR1 (Wang et al. 2005, 2006). Representative members of this group show a peak of induction between 5 and 12 h post SA treatment (WRKY38, UGT76B1, NIMIN1, NIMIN2, LLP in Fig. 2; BiP2 in (Wang et al. 2005)), while induction of PR-1 gene, a marker for late NPR1-dependent SAIGs, peaks after 24 h of treatment (Fig. 2).

A new SA-responsive promoter element named TL-1 element (TTCTTCTTC) was found to be over-represented in a group of early NPR1-dependent SAIGs (Wang et al. 2005). This element is functional in the Arabidopsis BiP2 promoter where SA activates binding of factors to TL-1 element by promoting its translocation to the nucleus (Wang et al. 2005). The nature of the factor(s) that recognize this TL-1 sequence is still unknown. Interestingly, we found the same TL-1 element over-represented in the group of 197 early NPR1-dependent SAIGs identified in this work (Table 5). Furthermore, expression analysis of NIMIN1 and LLP (representative early NPR1-dependent SAIGs) in response to SA in the tga2-1/tga5-1/tga6-1 triple mutant also indicates involvement of TGA2/5/6 factors in the activation of these genes by SA (Fig. 4). We propose that TGA boxes (TGACG), such as those found in the Arabidopsis PR-1 promoter, are recognized by TGA2/5/6 factors in promoters of early NPR1-dependent SAIGs (Fig. 6). In this case, requirement of NPR1 for activation of these genes by SA (Fig. 2), together with data from the literature indicating that NPR1 provides the transactivation activity to the TGA2-TGA box complex (Rochon et al. 2006), allow us to propose involvement of the NPR1-TGA2-TGA box ternary complex in the activation by SA of early NPR1-dependent SAIGs (Fig. 6). In this case, the question of how is NPR1 activated/reduced without de novo protein synthesis at the time these genes are induced remains open.

Mechanistic studies performed with PR1 gene, a marker for the group of late NPR1-dependent SAIGs (Lebel et al. 1998; Maleck et al. 2000; Rochon et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2006; Eulgem and Somssich 2007; Kesarwani et al. 2007) support the involvement of positive and negative W and TGA boxes in its SA-mediated activation, recognized by WRKY and TGA2/5/6 factors.

Taken together, our findings support the idea that SA can use different mechanisms to activate early and late SAIGs. Proper combination of SA-responsive elements (as-1-like, TGA box, W box and TL-1 element) in SAIGs promoters which are recognized by factors that act as repressors, or by complexes of factors and co-activators acting as enhancers, seems to be responsible for SA-controlled expression of these genes. Temporal control of gene expression by SA could be explained by reversible changes in the cellular redox homeostasis produced by SA. Interestingly, components of the transcriptional machinery involved in the expression of early and late SAIGs, such as NPR1, TGA factors, TGA box and as-1-like elements, seem to act as redox sensors for temporal control of gene expression by SA.

References

AbuQamar S, Chen X, Dhawan R, Bluhm B, Salmeron J, Lam S, Dietrich RA, Mengiste T (2006) Expression profiling and mutant analysis reveals complex regulatory networks involved in Arabidopsis response to Botrytis infection. Plant J 48:28–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02849.x

Allemeersch J, Durinck S, Vanderhaeghen R, Alard P, Maes R, Seeuws K, Bogaert T, Coddens K, Deschouwer K, Van Hummelen P, Vuylsteke M, Moreau Y, Kwekkeboom J, Wijfjes AH, May S, Beynon J, Hilson P, Kuiper MT (2005) Benchmarking the CATMA microarray. A novel tool for Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis. Plant Physiol 137:588–601. doi:10.1104/pp.104.051300

Alvarez ME (2000) Salicylic acid in the machinery of hypersensitive cell death and disease resistance. Plant Mol Biol 44:429–442. doi:10.1023/A:1026561029533

Aufsatz W, Amry D, Grimm C (1998) The ECS1 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a plant cell wall-associated protein and is potentially linked to a locus influencing resistance to Xanthomonas campestris. Plant Mol Biol 38:965–976

Baerson SR, Sanchez-Moreiras A, Pedrol-Bonjoch N, Schulz M, Kagan IA, Agarwal AK, Reigosa MJ, Duke SO (2005) Detoxification and transcriptome response in Arabidopsis seedlings exposed to the allelochemical benzoxazolin-2(3H)-one. J Biol Chem 280:21867–21881

Blanco F, Garreton V, Frey N, Dominguez C, Perez-acle T, Van Der Straeten D, Jordana X, Holuigue L (2005) Identification of NPR1-dependent and independent genes early induced by salicylic acid treatment in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 59:929–946. doi:10.1007/s11103-005-2227-x

Borner GH, Lilley KS, Stevens TJ, Dupree P (2003) Identification of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. A proteomic and genomic analysis. Plant Physiol 132:568–577

Brazier-Hicks M, Edwards R (2005) Functional importance of the family 1 glucosyltransferase UGT72B1 in the metabolism of xenobiotics in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 42:556–566

Brenner WG, Romanov GA, Kollmer I, Burkle L, Schmulling T (2005) Immediate-early and delayed cytokinin response genes of Arabidopsis thaliana identified by genome-wide expression profiling reveal novel cytokinin-sensitive processes and suggest cytokinin action through transcriptional cascades. Plant J 44:314–333

Bruneau L, Chapman R, Marsolais F (2006) Co-occurrence of both L-asparaginase subtypes in Arabidopsis: At3g16150 encodes a K+-dependent L-asparaginase. Planta 224:668–679

Butterbrodt T, Thurow C, Gatz C (2006) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of the tobacco PR-1a- and the truncated CaMV 35S promoter reveals differences in salicylic acid-dependent TGA factor binding and histone acetylation. Plant Mol Biol 61:665–674. doi:10.1007/s11103-006-0039-2

Cai XZ, Xu QF, Wang CC, Zheng Z (2006) Development of a virus-induced genesilencing system for functional analysis of the RPS2-dependent resistance signalling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 62:223–232

Cao H, Bowling SA, Gordon AS, Dong X (1994) Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 6:1583–1592

Catarecha P, Segura MD, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Garcia-Ponce B, Lanza M, Solano R, Paz-Ares J, Leyva A (2007) A mutant of the Arabidopsis phosphate transporter PHT1;1 displays enhanced arsenic accumulation. Plant Cell 19:1123–1133

Chen Z, Silva H, Klessig D (1993) Active oxygen species in the induction of plant systemic acquired resistance by salicylic acid. Science 262:1883–1886. doi:10.1126/science.8266079

Coates JC (2003) Armadillo repeat proteins: beyond the animal kingdom. Trends Cell Biol 13:463–471

Consonni C, Humphry ME, Hartmann HA, Livaja M, Durner J, Westphal L, Vogel J, Lipka V, Kemmerling B, Schulze-Lefert P, Somerville SC, Panstruga R (2006) Conserved requirement for a plant host cell protein in powdery mildew pathogenesis. Nat Genet 38:716–720

Dat J, Capelli N, Breusegem FV (2007) The interplay between salicylic acid and reactive oxygen species during cell death in plants. In: Hayat S, Ahmad A (eds) Salicylic acid—a plant hormone. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 247–276

De Leon IP, Sanz A, Hamberg M, Castresana C (2002) Involvement of the Arabidopsis aDOX1 fatty acid dioxygenase in protection against oxidative stress and cell death. Plant J 29:61–72

Delaney TP, Uknes S, Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Weymann K (1994) A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science 266:1247–1250. doi:10.1126/science.266.5188.1247

Delessert C, Kazan K, Wilson IW, Straeten DVD, Manners J, Dennis ES, Dolferus R (2005) The transcription factor ATAF2 represses the expression of pathogenesis-related genes in Arabidopsis. Plant J 43:745–757. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02488.x

Despres C, Chubak C, Rochon A, Clark R, Bethune T, Desveaux D, Fobert PR (2003) The Arabidopsis NPR1 disease resistance protein is a novel cofactor that confers redox regulation of DNA binding activity to the basic domain/Leucine Zipper Transcription Factor TGA1. Plant Cell 15:2181–2191. doi:10.1105/tpc.012849

Devaiah BN, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG (2007) WRKY75 transcription factor is a modulator of phosphate acquisition and root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143:1789–1801. doi:10.1104/pp.106.093971

Dunkley TPJ, Watson R, Griffin JL, Dupree P, Lilley KS (2004) Localization of organelle proteins by isotope tagging (LOPIT). Mol Cell Proteomics 3:1128–1134

Durrant WE, Dong X (2004) Systemic acquired resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42:185–209. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421

Edwards R, Dixon DP, Helmut S, Lester P (2005) Plant glutathione transferases. In: Methods in enzymology. Academic Press, New York, pp 169–186

Eulgem T (2005) Regulation of the Arabidopsis defense transcriptome. Trends Plant Sci 10:71–78. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.006

Eulgem T, Somssich IE (2007) Networks of WRKY transcription factors in defense signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10:366–371. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.020

Eulgem T, Weigman V, Mc HC, Dowell J, Holub E, Glazebrook J, Zhu T, Dangl J (2004) Gene expression signatures from three genetically separable resistance gene signaling pathways for downy mildew resistance. Plant Physiol 135:1129–1144. doi:10.1104/pp.104.040444

Fobert PR, Despres C (2005) Redox control of systemic acquired resistance. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8:378–382. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.003

Foyer CH, Noctor G (2005) Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell 17:1866–1875. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.033589

Fujita M, Fujita Y, Noutoshi Y, Takahashi F, Narusaka Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (2006) Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: a current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9:436–442. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.014

Gaffney T, Friedrich L, Vernooij B, Negrotto D, Nye G, Uknes S, Ward E, Kessmann H, Ryals J (1993) Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science 250:754–756. doi:10.1126/science.261.5122.754

Garreton V, Carpinelli J, Jordana X, Holuigue L (2002) The as-1 promoter element is an oxidative stress-responsive element and salicylic acid activates it via oxidative species. Plant Physiol 130:1516–1526. doi:10.1104/pp.009886

Gechev TS, Minkov IN, Hille J (2005) Hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death in Arabidopsis: transcriptional and mutant analysis reveals a role of an oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase gene in the cell death process. IUBMB Life 57:181–188. doi:10.1080/15216540500090793

Glazebrook J (2005) Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 43:9.1–9.13

Glazebrook J, Chen W, Estes B, Chang H-S, Nawrath C, Metraux J-P, Zhu T, Katagiri F (2003) Topology of the network integrating salicylate and jasmonate signal transduction derived from global expression phenotyping. Plant J 34:217–228. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01717.x

Gobert A, Park G, Amtmann A, Sanders D, Maathuis FJ (2006) Arabidopsis thaliana cyclic nucleotide gated channel 3 forms a non-selective ion transporter involved in germination and cation transport. J Exp Bot 57:791–800

Grant M, Lamb C (2006) Systemic immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9:414–420. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.013

Gutierrez RA, Ewing RM, Cherry JM, Green PJ (2002) Identification of unstable transcripts in Arabidopsis by cDNA microarray analysis: rapid decay is associated with a group of touch- and specific clock-controlled genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:11513–11518. doi:10.1073/pnas.152204099

He Ya, Gan S (2001) Identical promoter elements are involved in regulation of the OPR1 gene by senescence and jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 47:595–605

He Z-H, He D, Kohorn BD (1998) Requirement for the induced expression of a cell wall associated receptor kinase for survival during the pathogen response. Plant J 14:55–63

Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T (1999) Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res 27:297–300. doi:10.1093/nar/27.1.297

Hilson P, Allemeersch J, Altmann T, Aubourg S, Avon A, Beynon J, Bhalerao RP, Bitton F, Caboche M, Cannoot B, Chardakov V, Cognet-Holliger C, Colot V, Crowe M, Darimont C, Durinck S, Eickhoff H, de Longevialle AF, Farmer EE, Grant M, Kuiper MT, Lehrach H, Leon C, Leyva A, Lundeberg J, Lurin C, Moreau Y, Nietfeld W, Paz-Ares J, Reymond P, Rouze P, Sandberg G, Segura MD, Serizet C, Tabrett A, Taconnat L, Thareau V, Van Hummelen P, Vercruysse S, Vuylsteke M, Weingartner M, Weisbeek PJ, Wirta V, Wittink FR, Zabeau M, Small I (2004) Versatile gene-specific sequence tags for Arabidopsis functional genomics: transcript profiling and reverse genetics applications. Genome Res 14:2176–2189. doi:10.1101/gr.2544504

Holuigue L, Salinas P, Blanco F, Garretón V (2007) Salicylic acid and reactive oxygen species in the activation of stress defense genes. In: Hayat S, Ahmad A (eds) Salicylic acid—a plant hormone. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 197–246

Hong Z, Zhang Z, Olson JM, Verma DPS (2001) A novel UDP-glucose transferase is part of the callose synthase complex and interacts with phragmoplastin at the forming cell plate. Plant Cell 13:769–779

Horvath DM, Huang DJ, Chua NH (1998) Four classes of salicylate-induced tobacco genes. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 11:895–905. doi:10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.9.895

Houston NL, Fan C, Xiang Q-Y, Schulze J-M, Jung R, Boston RS (2005) Phylogenetic analyses identify 10 classes of the protein disulfide isomerase family in plants, including single-domain protein disulfide isomerase-related proteins. Plant Physiol 137:762–778

Ishiyama K, Inoue E, Watanabe-Takahashi A, Obara M, Yamaya T, Takahashi H (2004) Kinetic properties and ammonium-dependent regulation of cytosolic isoenzymes of glutamine synthetase in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 279:16598–16605

Ito T, Takahashi N, Shimura Y, Okada K (1997) A serine/threonine protein kinase gene isolated by an in vivo binding procedure using the Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene product, AGAMOUS. Plant Cell Physiol 38:248–258

Jackson RG, Lim E-K, Li Y, Kowalczyk M, Sandberg G, Hoggett J, Ashford DA, Bowles DJ (2001) Identification and biochemical characterization of an Arabidopsis indole-3-acetic acid glucosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 276:4350–4356

Janda T, Horváth E, Salía G, Páldi E (2007) Role of salicylic acid in the induction of abiotic stress tolerance. In: Hayat S, Ahmad A (eds) Salicylic acid—a plant hormone. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 91–150

Johnson C, Glover G, Arias J (2001) Regulation of DNA binding and trans-activation by a xenobiotic stress-activated plant transcription factor. J Biol Chem 276:172–178. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005143200

Jupin I, Chua NH (1996) Activation of the CaMV as-1 cis-element by salicylic acid: differential DNA-binding of a factor related to TGA1a. EMBO J 15:5679–5689

Katagiri F (2004) A global view of defense gene expression regulation—a highly interconnected signaling network. Curr Opin Plant Biol 7:506–511. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.013

Kesarwani M, Yoo J, Dong X (2007) Genetic interactions of TGA transcription factors in the regulation of pathogenesis-related genes and disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 144:336–346. doi:10.1104/pp.106.095299

Krawczyk S, Thurow C, Niggeweg R, Gatz C (2002) Analysis of the spacing between the two palindromes of activation sequence-1 with respect to binding to different TGA factors and transcriptional activation potential. Nucleic Acids Res 30:775–781. doi:10.1093/nar/30.3.775

Krinke O, Ruelland E, Valentova O, Vergnolle C, Renou JP, Taconnat L, Flemr M, Burketova L, Zachowski A (2007) Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase activation is an early response to salicylic acid in Arabidopsis suspension cells. Plant Physiol 144:1347–1359. doi:10.1104/pp.107.100842

Langlois-Meurinne M, Gachon CM, Saindrenan P (2005) Pathogen-responsive expression of glycosyltransferase genes UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 is necessary for resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 139:1890–1901. doi:10.1104/pp.105.067223

Laule O, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Hruz T, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P (2006) Web-based analysis of the mouse transcriptome using Genevestigator. BMC Bioinformatics 7:311. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-7-311

Lawton KA, Friedrich L, Hunt M, Weymann K, Delaney T, Kessmann H, Staub T, Ryals J (1996) Benzothiadiazole induces disease resistance in Arabidopsis by activation of the systemic acquired resistance signal transduction pathway. Plant J 10:71–82. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10010071.x

Lebel E, Heifetz P, Thorne L, Uknes S, Ryals J, Ward E (1998) Functional analysis of regulatory sequences controlling PR-1 gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J 16:223–233. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00288.x

Lidder P, Gutierrez RA, Salome PA, McClung CR, Green PJ (2005) Circadian control of messenger RNA stability. Association with a sequence-specific messenger RNA decay pathway. Plant Physiol 138:2374–2385. doi:10.1104/pp.105.060368

Lieberherr D, Wagner U, Dubuis PH, Metraux JP, Mauch F (2003) The rapid induction of glutathione S-transferases AtGSTF2 and AtGSTF6 by avirulent Pseudomonas syringae is the result of combined salicylic acid and ethylene signaling. Plant Cell Physiol 44:750–757. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcg093

Lim EK, Bowles DJ (2004) A class of plant glycosyltransferases involved in cellular homeostasis. EMBO J 23:2915–2922. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600295

Liu G, Holub EB, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Fobert PR (2005) An Arabidopsis NPR1-like gene, NPR4, is required for disease resistance. Plant J 41:304–318

Loake G, Grant M (2007) Salicylic acid in plant defence—the players and protagonists. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10:466–472. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.008

Loque D, Yuan L, Kojima S, Gojon A, Wirth J, Gazzarrini S, Ishiyama K, Takahashi H, von Wiren N (2006) Additive contribution of AMT1;1 and AMT1;3 to high-affinity ammonium uptake across the plasma membrane of nitrogen-deficient Arabidopsis roots. Plant J 48:522–534

Lu H, Rate DN, Song JT, Greenberg JT (2003) ACD6, a novel ankyrin protein, is a regulator and an effector of salicylic acid signaling in the Arabidopsis defense response. Plant Cell 15:2408–2420

Lurin C, Andres C, Aubourg S, Bellaoui M, Bitton F, Bruyere C, Caboche M, Debast C, Gualberto J, Hoffmann B, Lecharny A, Le Ret M, Martin-Magniette M-L, Mireau H, Peeters N, Renou J-P, Szurek B, Taconnat L, Small I (2004) Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 16:2089–2103. doi:10.1105/tpc.104.022236

Mahalingam R, Shah N, Scrymgeour A, Fedoroff N (2005) Temporal evolution of the Arabidopsis oxidative stress response. Plant Mol Biol 57:709–730. doi:10.1007/s11103-005-2860-4

Maleck K, Levine A, Eulgem T, Morgan A, Schmid J, Lawton KA, Dangl JL, Dietrich RA (2000) The transcriptome of Arabidopsis thaliana during systemic acquired resistance. Nat Genet 26:403–410. doi:10.1038/82521

Mao P, Duan M, Wei C, Li Y (2007) WRKY62 transcription factor acts downstream of cytosolic NPR1 and negatively regulates jasmonate-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell Physiol 48:833–842

Mateo A, Funck D, Muhlenbock P, Kular B, Mullineaux PM, Karpinski S (2006) Controlled levels of salicylic acid are required for optimal photosynthesis and redox homeostasis. J Exp Bot 57:1795–1807. doi:10.1093/jxb/erj196

Mou Z, Fan W, Dong X (2003) Inducers of plant systemic acquired resistance regulate NPR1 function through redox changes. Cell 113:935–944. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00429-X

Ndamukong I, Abdallat AA, Thurow C, Fode B, Zander M, Weigel R, Gatz C (2007) SA-inducible Arabidopsis glutaredoxin interacts with TGA factors and suppresses JA-responsive PDF1.2 transcription. Plant J 50:128–139. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03039.x

Niggeweg R, Thurow C, Kegler C, Gatz C (2000) Tobacco Transcription Factor TGA2.2 is the main component of as-1-binding Factor ASF-1 and is involved in salicylic acid- and auxin-inducible expression of as-1-containing target promoters. J Biol Chem 275:19897–19905. doi:10.1074/jbc.M909267199

Orgil U, Araki H, Tangchaiburana S, Berkey R, Xiao S (2007) Intraspecific genetic variations, fitness cost and benefit of RPW8, a disease resistance locus in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 176:2317–2333

Overmyer K, Brosche M, Kangasjarvi J (2003) Reactive oxygen species and hormonal control of cell death. Trends Plant Sci 8:335–342. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00135-3

Park AR, Cho SK, Yun UJ, Jin MY, Lee SH, Sachetto-Martins G, Park OK (2001) Interaction of the Arabidopsis receptor protein kinase Wak1 with a glycine-rich protein, AtGRP-3. J Biol Chem 276:26688–26693

Pavet V, Quintero C, Cecchini NM, Rosa AL, Alvarez ME (2006) Arabidopsis displays centromeric DNA hypomethylation and cytological alterations of heterochromatin upon attack by pseudomonas syringae. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:577–587. doi:10.1094/MPMI-19-0577

Pontier D, Miao ZH, Lam E (2001) Trans-dominant suppression of plant TGA factors reveals their negative and positive roles in plant defense responses. Plant J 27:529–538. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01086.x

Pourtau N, Jennings R, Pelzer E, Pallas J, Wingler A (2006) Effect of sugar-induced senescence on gene expression and implications for the regulation of senescence in Arabidopsis. Planta 224:556–568

Puskas LG, Zvara A, Hackler L Jr, Van Hummelen P (2002) RNA amplification results in reproducible microarray data with slight ratio bias. Biotechniques 32:1330–1334, 1336, 1338, 1340

Qin XF, Holuigue L, Horvath DM, Chua NH (1994) Immediate early transcription activation by salicylic acid via the cauliflower mosaic virus as-1 element. Plant Cell 6:863–874

Quiel JA, Bender J (2003) Glucose conjugation of anthranilate by the Arabidopsis UGT74F2 glucosyltransferase is required for tryptophan mutant blue fluorescence. J Biol Chem 278:6275–6281

Rampey RA, Woodward AW, Hobbs BN, Tierney MP, Lahner B, Salt DE, Bartel B (2006) An Arabidopsis basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper protein modulates metal homeostasis and auxin conjugate responsiveness. Genetics 174:1841–1857

Rao MV, Davis KR (1999) Ozone-induced cell death occurs via two distinct mechanisms in Arabidopsis: the role of salicylic acid. Plant J 17:603–614. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00400.x

Rochon A, Boyle P, Wignes T, Fobert PR, Despres C (2006) The coactivator function of Arabidopsis NPR1 requires the core of its BTB/POZ domain and the oxidation of C-terminal cysteines. Plant Cell 18:3670–3685. doi:10.1105/tpc.106.046953

Rohde A, Morreel K, Ralph J, Goeminne G, Hostyn V, De Rycke R, Kushnir S, Van Doorsselaere J, Joseleau J-P, Vuylsteke M, Van Driessche G, Van Beeumen J, Messens E, Boerjan W (2004) Molecular phenotyping of the pal1 and pal2 mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals far-reaching consequences on phenylpropanoid, amino acid, and carbohydrate metabolism. Plant Cell 16:2749–2771

Rouhier N, Lemaire SD, Jacquot J-P (2008) The role of glutathione in photosynthetic organisms: emerging functions for glutaredoxins and glutathionylation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59:143–166. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092811

Ruepp A, Zollner A, Maier D, Albermann K, Hani J, Mokrejs M, Tetko I, Guldener U, Mannhaupt G, Munsterkotter M, Mewes HW (2004) The FunCat, a functional annotation scheme for systematic classification of proteins from whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 32:5539–5545. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh894

Sakai T, Honing Hvd, Nishioka M, Uehara Y, Takahashi M, Fujisawa N, Saji K, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Jones MA, Smirnoff N, Okada K, Wasteneys GO (2008) Armadillo repeat-containing kinesins and a NIMA-related kinase are required for epidermal-cell morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J 53:157–171

Sappl PG, Onate-Sanchez L, Singh KB, Millar AH (2004) Proteomic analysis of glutathione S-transferases of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals differential salicylic acid-induced expression of the plant-specific phi and tau classes. Plant Mol Biol 54:205–219. doi:10.1023/B:PLAN.0000028786.57439.b3

Sato M, Mitra RM, Coller J, Wang D, Spivey NW, Dewdney J, Denoux C, Glazebrook J, Katagiri F (2007) A high-performance, small-scale microarray for expression profiling of many samples in Arabidopsis–pathogen studies. Plant J 49:565–577

Shahollari B, Vadassery J, Varma A, Oelmüller R (2007) A leucine-rich repeat protein is required for growth promotion and enhanced seed production mediated by the endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 50:1–13

Shirasu K, Nakajima H, Rajasekhar VK, Dixon RA, Lamb C (1997) Salicylic acid potentiates an agonist-dependent gain control that amplifies pathogen signals in the activation of defense mechanisms. Plant Cell 9:261–270

Stange C, Ramirez I, Gomez I, Jordana X, Holuigue L (1997) Phosphorylation of nuclear proteins directs binding to salicylic acid-responsive elements. Plant J 11:1315–1324. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11061315.x

Stanley KH, Yu Y, Snesrud EC, Moy LP, Linford LD, Haas BJ, Nierman WC, Quackenbush J (2005) Transcriptional divergence of the duplicated oxidative stress-responsive genes in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant J 41:212–220

Summermatter K, Sticher L, Metraux JP (1995) Systemic responses in Arabidopsis thaliana infected and challenged with Pseudomonas syringae pv syringae. Plant Physiol 108:1379–1385

Surplus SL, Jordan BR, Murphy AM, Carr JP, Thomas B, Mackerness SAH (1998) Ultraviolet-B-induced responses in Arabidopsis thaliana: role of salicylic acid and reactive oxygen species in the regulation of transcripts encoding photosynthetic and acidic pathogenesis-related proteins. Plant Cell Environ 21:685–694. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00325.x

Tada Y, Spoel SH, Pajerowska-Mukhtar K, Mou Z, Song J, Wang C, Zuo J, Dong X (2008) Plant immunity requires conformational charges of NPR1 via S-nitrosylation and thioredoxins. Science 321:952–956. doi:10.1126/science.1156970

Taji T, Seki M, Satou M, Sakurai T, Kobayashi M, Ishiyama K, Narusaka Y, Narusaka M, Zhu J-K, Shinozaki K (2004) Comparative genomics in salt tolerance between Arabidopsis and Arabidopsis-related halophyte salt cress using Arabidopsis microarray. Plant Physiol 135:1697–1709

Tamaoki M, Nakajima N, Kubo A, Aono M, Matsuyama T, Saji H (2003) Transcriptome analysis of O3-exposed Arabidopsis reveals that multiple signal pathways act mutually antagonistically to induce gene expression. Plant Mol Biol 53:443–456

Tao Y, Xie Z, Chen W, Glazebrook J, Chang HS, Han B, Zhu T, Zou G, Katagiri F (2003) Quantitative nature of Arabidopsis responses during compatible and incompatible interactions with the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Cell 15:317–330. doi:10.1105/tpc.007591

Thatcher LF, Carrie C, Andersson CR, Sivasithamparam K, Whelan J, Singh KB (2007) Differential gene expression and subcellular targeting of Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase F8 is achieved through alternative transcription start sites. J Biol Chem 282:28915–28928

Thibaud-Nissen F, Wu H, Richmond T, Redman JC, Johnson C, Green R, Arias J, Town CD (2006) Development of Arabidopsis whole-genome microarrays and their application to the discovery of binding sites for the TGA2 transcription factor in salicylic acid-treated plants. Plant J 47:152–162. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02770.x

Thijs G, Marchal K, Lescot M, Rombauts S, De Moor B, Rouze P, Moreau Y (2002) A Gibbs sampling method to detect overrepresented motifs in the upstream regions of coexpressed genes. J Comput Biol 9:447–464. doi:10.1089/10665270252935566

Thurow C, Schiermeyer A, Krawczyk S, Butterbrodt T, Nickolov K, Gatz C (2005) Tobacco bZIP transcription factor TGA2.2 and related factor TGA2.1 have distinct roles in plant defense responses and plant development. Plant J 44:100–113. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02513.x

Titarenko E, Rojo E, Leon J, Sanchez-Serrano JJ (1997) Jasmonic acid-dependent and -independent signaling pathways control wound-induced gene activation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 115:817–826

Uquillas C, Letelier I, Blanco F, Jordana X, Holuigue L (2004) NPR1-independent activation of immediate early salicylic acid-responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 17:34–42. doi:10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.1.34

van Loon LC, Rep M, Pieterse CMJ (2006) Significance of inducible defense-related proteins in infected plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 44:135–162. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143425