Abstract

Injectable drug delivery systems (DDS) such as particulate carriers and water-soluble polymers are being used and developed for a wide variety of therapeutic applications. However, a number of immunological risks with serious clinical implications are associated with administration of DDS. These immunological events can compromise the efficacy and safety of these systems by changing the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and targeting capability of DDS, and by inducing hypersensitivity reactions. Antibodies induced by administration of DDS can be directed against the carrier material, the drug and/or targeting ligands associated with the DDS. Complement activation and opsonization of DDS, which may or may not be associated with antibody formation, may lead to accelerated clearance, hypersensitivity reactions and formation of membrane attack complexes resulting in premature release of the drug. Also platelets have been reported to play a role in DDS immunogenicity. Despite our curtailed understanding of the relationships between physicochemical characteristics and immunogenicity of DDS, several risk factors have been identified. Insight into these factors should be employed in the development of novel DDS with low immunological risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Injectable drug delivery systems (DDS) play an increasingly important role in the administration of therapeutic drugs since more of these systems are becoming commercially available for a wide variety of applications. There are many different types of DDS (e.g. polymer-based nanoparticles and microparticles, lipid-based nanocarriers, water-soluble polymer–drug conjugates, etc.) and they offer several advantages over conventional dosage forms. In particular, controlled release and targeting of active substances (small molecules, proteins or genes) to the desired site of action is being exploited to improve the delivery at the target site and avoid body sites which are sensitive to toxic drug actions (1–7). Liposomal DDS like Doxil and Ambisome have been on the market already for decades, whereas other liposomal drugs are in various stages of clinical development (8,9). Also several peptide-loaded PLGA-based microparticles are available for the treatment of prostate cancer and other diseases, while PLGA nanoparticles are being developed for the (targeted) delivery of proteins, DNA and vaccines (6). Furthermore, efficient anticancer drugs based on nanosized conjugates of linear hydroxypropyl methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymers, various molecular and supramolecular structures of the HPMA copolymers and polymer micelles, conjugated with biologically active proteins, low-molecular-weight drugs and/or targeting ligands, have been developed (10,11).

Remarkably, little attention has been paid to the potential immunogenicity, i.e. the capability of a substance or device to elicit an immune response, of injectable DDS. Whereas the immunostimulatory effects of delivery systems have been well documented and exploited in the vaccine delivery field (12–14), the unwanted immunostimulatory effects of the same or similar carriers when used as DDS have received much less attention. At first instance this may not be surprising as the major drives in this field are the drug and the disease to be treated. Therefore most investigators focus on kinetic and therapeutic improvements and drug-related toxicity of the products, rather than the immunological risks associated with the administration of the DDS. However, adverse immunological effects associated with the application of DDS may pose serious risks to patients.

Immunogenicity of DDS can have severe clinical implications, such as reduced efficacy, immune responses after repeated administration of a DDS (containing the same or a different drug), or acute reactions. There is an urgent need to increase our understanding of the physicochemical characteristics that determine immunological reactions against injectable DDS already in clinical use or development, such as liposomes, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) based systems and hydroxypropyl methacrylate copolymer (HPMA)–drug conjugates (15–17). Here we will review the literature on immunological risks associated with the use of injectable DDS. Our survey is primarily focused on specific antibody-mediated responses. Immunotoxicity of DDS, which has been extensively reviewed elsewhere (7,18–22), is also addressed. Causes and consequences of immunological responses against carriers, encapsulated drugs and targeting ligands will be described and illustrated with examples. Moreover, relationships between physicochemical characteristics of DDS immunological risks associated with their use will be discussed.

ANTIBODIES AGAINST DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Antibodies Against the Carrier Material

Data on antibody responses against DDS are available mainly for liposomes (23). Lipid A-containing liposomes administered with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant (FIA, a mineral oil) in animals has been reported to induce antibodies against phosphatidyl choline and other phospholipids (24,25) as well as cholesterol if incorporated in large amounts (71 mol%) (26–28). Although anti-lipid antibodies in principle can cross-react with endogenous lipids, these antibodies are unlikely to interact with cell surfaces because these are sterically protected by coverage with large molecules such as glycolipids and proteins (23,29,30). However, formation of antibodies against liposomes may have major implications for the pharmacokinetic profile of liposomal carriers, in particular through complement activation (7,31) and opsonization (32).

The above-mentioned studies on the immunogenicity of liposomes and liposomal lipids were conducted in the presence of adjuvants. Although this may not be representative for the administration of liposomes in a therapeutic context, recent publications show evidence of antibody (mainly IgM) responses in mice and rats against non-adjuvanted PEGylated liposomes intended for therapeutic use, resulting in rapid blood clearance (33–39). Antibody responses were shown to be maintained in T cell-deficient animals but not in B cell deficient or splenectomized animals, pointing to a T cell-independent mechanism requiring marginal zone B cells in the spleen (34,36,37). Furthermore, IgM was claimed to clear PEGylated compounds far more rapidly and complete than IgG antibodies do, since the pentameric structure of IgM promotes the formation of larger immune complexes and activates complement more efficiently than IgG does (35).

Although the literature describing anti-DDS antibodies is largely restricted to liposomal carriers, there is no fundamental reason why antibodies would not be formed against other DDS, including polymeric DDS. Polymers by definition contain repeat units, which may trigger B cell activation and hence antibody production (40,41), as discussed below. Indeed the formation of anti-PEG antibodies has been observed in patients treated with PEGylated proteins and found to be correlated with accelerated clearance and reduced activity of the drugs (42,43). Also, HPMA copolymers and other water-soluble polymers have shown to be immunogenic in mice, although antibody levels are generally low (44,45). Antibodies against HPMA–drug conjugates were reported to be predominantly, though not exclusively, directed to the drug (45). Conjugation of avidin to HPMA did not affect the moderate IgM response against the polymer when administered to mice in the presence of alum (46). Repeated administration of empty polyacryl starch microparticles in mice did not induce detectable antibody levels (47).

Encapsulated drugs may increase or reduce antibody responses against the carrier. When human serum albumin was entrapped in the above-mentioned polyacryl starch microparticles, repeated administration in mice resulted in antibodies directed not only against the protein but also against the particle matrix (47). Semple et al. showed that loading of PEGylated liposomes with antisense oligonucleotide or plasmid DNA enhanced the anti-PEG antibody responses in several mouse strains (37). Interestingly, this effect was found to be independent of the presence of immunostimulatory CpG motifs in the drug. In contrast, PEGylated liposomes containing encapsulated doxorubicin induced lower IgM levels in rats than empty PEGylated liposomes did, likely due to the toxicity of doxorubicin for immune cells (33).

Antibodies Against Drugs

It is well known that conjugation of haptens (i.e., small molecules that can act as B cell epitopes if bound to a carrier) to proteins can render them immunogenic, no matter whether or not the hapten is an endogenous compound. For instance, steroid hormones and cholesterol were shown to become immunogenic in rabbits by conjugation to human albumin (48); paracetamol (acetaminophen) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase elicited anti-paracetamol antibodies in mice (49). Whereas these examples illustrate the immunogenicity of haptens conjugated to proteins, thereby providing them with T-helper epitopes, the conjugation of haptens with non-proteinaceous carriers (which lack T-helper epitopes) can also make them immunogenic. Examples include acrylamide–dinitrophenyl (DNP) conjugates (50–52), dextran-trinitrophenyl (TNP) and polyacrylamide–TNP conjugates (53), and various HPMA–drug conjugates (45).

Not only chemical conjugation but also noncovalent association of small molecules in a particulate carrier can render them immunogenic. Incorporation of gangliosides in lipid A-containing liposomes was shown to generate anti-ganglioside antibodies in mice (54). Lipid A-containing liposomes with the cholesterol precursor squalene induced anti-squalene antibodies in mice (55), showing that even very hydrophobic compounds, which presumably are buried in the liposomal bilayer, can become immunogenic by liposomal association.

Particulate systems are widely used in vaccinology to increase the immunogenicity of intrinsically immunogenic proteins, such as bacterial and viral antigens. So, the encapsulation of foreign proteins in particulate DDS is likely to increase their immunogenicity. For instance, a significant increase in IgG1 levels following subcutaneous administration in mice of foreign proteins or protein–hapten conjugates encapsulated in PLGA particles was observed in comparison with the levels after administration of the free compounds (56). Ovalbumin covalently coupled to liposomes elicited higher antibody levels than soluble ovalbumin (57). Many other examples can be found in the vaccine literature (12–14).

Although the immunogenicity of soluble self proteins is low or absent, practically all recombinant human proteins are immunogenic in patients (58,59). As discussed later, the immunogenicity of self proteins can be enhanced by presentation in aggregated or particulate form (see below). Hence, association of recombinant human proteins with a particulate DDS may be a risk factor for immunogenicity.

Encapsulation of drugs in DDS does not always lead to increased anti-drug antibody levels, e.g. when the drug is cytotoxic or immunosuppressive. Tardi et al. showed that the antibody response in mice to ovalbumin covalently attached to the surface of liposomes was fully suppressed when doxorubicin was co-encapsulated in the liposomes (57). The immunosuppressive effect of doxorubicin has been ascribed to the toxic action of doxorubicin on macrophages or B cells (33,57).

In particular cases the incorporation of a drug into a delivery system can reduce its immunogenicity. This has been reported for recombinant human factor VIII (rFVIII). Approximately 15–30% of the patients treated with rFVIII develop inhibitory antibodies that neutralize the protein’s activity. For most of these patients rFVIII is a non-self protein because they do not produce endogenous factor VIII. Ramani et al. reported that hemophilic mice treated with subcutaneous injections of phosphatidyl serine (PS)-containing liposomal rFVIII (non-self protein) produced lower total- and inhibitory titers compared to mice having received rFVIII alone (60). This effect was ascribed to steric shielding of the immunodominant PS-binding site of rFVIII and an immunomodulatory effect of PS (61). Incorporation of rFVIII in PEGylated PS-containing liposomes resulted in a further reduction of rFVIII immunogenicity (62).

Reduced anti-drug antibody formation has also been observed for polymer–protein conjugates as compared to the free proteins (44–46). Several (self and non-self) proteins conjugated to high-molecular-weight (ca. 30 kDa) copolymer HPMA induced lower antibody titers in mice as compared to the free proteins. When the proteins were conjugated with PEG (M w 5,000) the immune response was also reduced albeit to a lesser extent, while conjugation to low-molecular-weight (ca. 3 kDa) HPMA did not reduce the immunogenicity of the proteins (45). It was hypothesized that antigenic epitopes of proteins bound to the high-molecular-weight HPMA copolymer were shielded and thereby had become unavailable for recognition by the immune system, a mechanism that has been suggested for PEGylated proteins as well (58).

The above-mentioned examples illustrate that the immunogenicity of a drug when incorporated in or conjugated with a DDS is largely unpredictable. When a drug is associated with a DDS its immunogenicity can be induced, enhanced as well as reduced.

Antibodies Against Targeting Ligands

DDS can be actively targeted to the desired site of action by covalently coupled targeting ligands, such as antibodies and receptors (1–5,63). A few reports have shown that this can lead to antibody responses against the ligand.

Philips and Dahman observed that free mouse IgG2a was not immunogenic after repeated injection in mice, whereas immunoliposomes (containing 0.9 mol% mouse IgG2a) induced anti-IgG2a antibodies (IgG1) impairing the targeting capacity of the liposomes in vivo (64). The presence of 5 mol% PEGylated phospholipid in the liposomal bilayer enhanced rather decreased the anti-IgG2a response.

Harding et al. (65) attached chimerized mouse IgG (C225, containing human Fc) covalently to the hydrazide end-groups of the PEG chains which were grafted onto the surface of liposomes. Whereas repeated intravenous administration of soluble C225 did not induce antibodies, a single injection of the immunoliposomes triggered an immune response in rats which was reflected in C225-specific (mainly Fc-specific) IgG titers. Subsequently injected immunoliposomes or free C225 were rapidly cleared from the blood circulation. This demonstrates that coupling of the IgG to liposomes renders it immunogenic.

Antibodies Against Linkers

In principle, a chemical linker to conjugate a drug or targeting ligand to a DDS, or to PEGylate a DDS, can give rise to the creation of new immunogenic epitopes, but evidence of linker-induced immunogenicity is lacking in the public domain. Since chemical linkers are sterically ‘trapped’ between the DDS and the drug or ligand moiety, especially in case of bulky ligands like antibodies, linker-induced immunogenicity may not be a major issue in most cases.

If the linker is proteinaceous in nature, e.g. avidin-biotin spacers which are commonly used in research, the linker might not only be immunogenic itself but also provide T-helper epitopes enhancing antibody responses against the DDS or incorporated drugs.

Why Do DDS Elicit Antibodies?

The previous sections have illustrated that antibodies can be formed against drug carriers, encapsulated drugs or targeting ligands. In this section we will explain why DDS-mediated drug delivery can induce antibody formation.

Practically all molecules or materials, including those made by our own body (i.e. self antigens), are antigenic (i.e., capable of reacting with components of the immune system). This is even true for compounds lacking any obvious functional groups, such as squalene and fullerenes (55,66). This implies that any molecule or DDS contains structures (B cell epitopes) that can be recognized by specific human B cell receptors (BCRs). Recognition of an epitope by a BCR in itself, however, is not sufficient to induce a strong antibody response; otherwise all endogenous molecules and structures in our body would be continuously attacked by our own immune system. Apparently an additional trigger is needed to render a molecule immunogenic (i.e., able to elicit an immune response). As will be explained below, the immunogenicity of a molecule depends both on its structure and on how it is presented to the immune system (Table I).

As many of the DDS/drug combinations for which immunogenicity has been described are non-protein based, and thus lack T cell epitopes, antibody formation should occur via a T cell independent mechanism. One common mechanism likely responsible for the formation of DDS-induced antibodies is the creation of multiple B cell epitopes by the DDS formulation, which is an intrinsic property of most DDS. Closely spaced B cell epitopes in repetitive arrays can directly activate B cells via a mechanism known for T cell-independent type 2 (TI-2) antigens (see (40) and references therein). TI-2 antigens must be repetitive to cluster and crosslink BCRs on the surface of the B cell. This BCR clustering initiates a complex signaling pathway, such as the activation of Bruton’s tyrosine kinases, which mediate B-cell proliferation leading to activation, proliferation and formation of antibodies against the antigen (40,67,68). The immune system has evolved to rigorously react to highly dense (spacing between 5–10 nm), repetitive epitope arrays that normally are present only on the surface of viruses and some bacteria, but not on mammalian cell surfaces (67). BCRs on the surface of resting B cells have been estimated to be about 40 nm apart; BCR crosslinking by epitope arrays can be achieved rapidly, since BCRs are ‘floating’ in the cell membrane of B cells and can be recruited at a velocity of ca. 300 nm/s (40).

Classical examples of TI-2 antigens include bacterial capsular polysaccharides used as vaccines (e.g., pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines), and haptens (i.e., small molecules that can act as B cell epitopes if bound to a carrier) conjugated to polymers. In 1976, Dintzis et al. showed that acrylamide substituted with 12 to 16 dinitrophenyl (DNP) haptens were very immunogenic, while free DNP as well as polymers containing less haptens per polymer did not elicit antibodies (50). Additional investigations confirmed that the immunogenicity of haptenated polymers is determined by a minimum hapten valency of 10–20 (51,52), but depends on the size of the polymers as well, requiring a threshold molecular mass of about 100 kDa (51). Moreover, ample evidence points to epitope spacings between 5–10 nm being a potent trigger for B cell activation (50,51,67,69–73). This principle has also been proposed as a mechanism for the immunogenicity of aggregated proteins (58,59). Brunswick et al. demonstrated that conjugation of anti-BCR (anti-IgD or anti-IgM) antibodies, or Fab fragments thereof, to dextran made them 1,000-fold more potent (as compared to the unconjugated antibodies) in B cell activation (74). This was later shown to be a representative model for the activation of B cells by TI-2 antigens conjugated to polymers (75).

Chackerian et al. (72) demonstrated that the density of self proteins on the surface of virus-like particles (VLPs) is crucial for the induction of an antibody response against these proteins. The closer the spacing, the higher was the resulting antibody response, being optimal at an epitope spacing of 5–10 nm, in line with that reported for polymer–hapten conjugates. Unlike self proteins, non-self proteins were shown to elicit antibodies also when not conjugated to VLPs (72,73). This suggests that “non-selfness” is a risk factor by itself, whereas a self antigen, like a small molecule, requires multimeric presentation to become immunogenic (Table I).

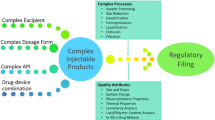

With the epitope array concept in mind, B cell activation and subsequent antibody responses can be expected after administration of particulate DDS or polymer–drug conjugates that contain highly repetitive B cell epitopes, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. Such epitope arrays can be created by the carrier material itself (e.g., the phospholipid head groups on liposomal surfaces, and polymers which by definition contain repeat units), the encapsulated or conjugated drugs if presented in arrays, or ligands attached to the carrier. For instance, common ligand concentrations on liposomal surfaces are between 0.5–2 mol% of the lipid content, corresponding to ca. 250–1,000 ligands on each 100-nm liposome with an average spacing between 5–10 nm. This perfectly matches the optimum epitope density for B cell activation and may explain the antibody responses against liposomal ligands (64,65), as described above.

Schematic illustration of the interaction of molecules (orange bullets, which can be drugs, targeting ligands, or repeat units of a polymer) with B cell receptors (BCRs, surface immunoglobulins on B cells). Interaction of the free, soluble molecules with BCRs leads to toleragenic signals (A). Interaction of the same molecules linked to a polymeric DDS (B) or a particulate DDS (C) with the BCRs leads to crosslinking of BCRs. The latter triggers a complex signaling pathway, such as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase activation, eventually resulting in B cell activation.

The examples of polymer–hapten conjugates have illustrated how non-immunogenic molecules can be turned into immunogenic structures. It can be anticipated that presentation of the same molecules on particulate carriers will show even stronger effects, as the immune system has evolved to recognize particulate materials as foreign (14). Indeed, insoluble polyacrylamide-trinitrophenyl (TNP) beads and dextran-TNP beads with high hapten densities activated B cells much more strongly than their soluble counterparts (polymer–TNP conjugates) did (53). Moreover, polymer–drug conjugates such as HPMA based systems seem less immunogenic than particulate drug carriers. These observations are also consistent with the conception that large, rigid systems are more immunogenic than smaller, more flexible structures (40,71). The general validity of this proposition, however, remains to be established. Another explanation for the low apparent immunogenicity of currently used conjugates is that the polymers are usually much smaller than the reported threshold size of 100 kDa required for raising an antibody response (51).

Besides the particulate character and the presence of repetitive B cell epitopes, additional risk factors can be provided by the presence of adjuvants. In particular, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) form an important adjuvant category (76), which includes Toll like receptor (TLR) ligands such as LPS or bacterial DNA (CpG) sequences. These adjuvants are stimulators of the innate immune system, capable of activating B cell clones specific for other antigens. Whereas TLR ligands are being utilized to enhance the potency of vaccines, they should be avoided in DDS but might be present as impurities or contaminants. Furthermore, TI-2 antibody responses can be rendered T cell dependent (TD) if T-helper epitopes are contained in the carrier, e.g. when the carrier is protein based or contains protein based drugs or ligands. In theory this would result in higher and more persistent antibody levels, because—besides direct activation of B cells—other TD mechanisms and generation of immunological memory may happen.

An important consequence of antibody formation against DDS is activation of the complement. Moreover, complement has been reported to enhance the BCR crosslinking signal (40). Complement activation, however, can also occur independently of (specific) antibodies, as discussed in the following section.

IMMUNOTOXICITY OF DDS

Complement Activation

The complement system plays an important role in the defense against pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria. One of the major functions of the complement is to label pathogens for subsequent elimination from the host. Depending on its properties, a DDS may be ‘seen’ as a pathogen and eliminated by the complement system. Consequences of DDS-induced complement activation include opsonization of the DDS resulting in rapid clearance by macrophages, hypersensitivity reactions and formation of membrane attack complexes (7,31,77), the latter being relevant for vesicular DDS.

There are three pathways leading to complement activation (see (7,41) for details and references), all of which may be induced by DDS related factors: (1) the classical pathway, initiated by antibodies bound to the surface of the DDS, (2) the alternative pathway, initiated by constituents of DDS surfaces, and (3) the lectin pathway, activated by carbohydrate-recognizing proteins bound to the DDS surface (Fig. 2). DDS-mediated complement activatin occurs predominantly via the first two pathways (78–81) and the lectin pathway will come into play for mannosylated DDS (63).

DDS-mediated activation pathways of the complement system (adapted from (81)). For further details see text.

All three pathways involve activation of C3 by C3 convertase, which cleaves C3 that is bound to the particle (pathogen or DDS) surface in the fragments C3a and C3b. C3a plays a role in hypersensitivity reactions (see below). C3b and its fragment iC3b are the most abundant and important complement proteins. Interaction of surface bound C3 fragments with the C3 receptor on the surface of phagocytic cells leads to phagocytosis of these immune complexes (41,79,82,83). For liposomal DDS the activated complement can cause liposome destabilization by the formation of a membrane attack complex (MAC or C5b-9) (7,81). MAC formation induces leakage and release of the liposomal contents, resulting in increased toxicity or reduced activity, caused by higher drug concentrations at non-target sites or lower drug concentrations at the target sites, respectively (41,79).

The classical pathway is initiated by binding of IgM and IgG to foreign particles and subsequent binding of C1q to surface-bound IgM or IgG (41,80,84,85). IgM associated with PEGylated liposomes may work synergistically with complement components (C3b, iC3b) on the enhancement of liposome uptake by liver macrophages through receptor mediated endocytosis. Complement activation is strongly amplified through a cascade of enzymatic reactions. Antibodies, especially IgM, trigger and amplify this cascade, even in small amounts, implicating that the antibody mediated process may be the predominant mechanism (35,86).

In 1997 Alving et al. demonstrated that the activation of complement by cholesterol-containing liposomes involves the classical rather than alternative pathway (87). However, later reports indicate that liposomes can activate complement via both the classical and the alternative pathway. Liposomal complement activation is promoted by large size, polydispersity, positive or negative surface charge and high (>45%) cholesterol content (31,87). It has been shown that negatively charged liposomes activate complement primarily via the classical pathway (86,88) and positively charged liposomes do this via the alternative pathway (88,89), whereas neutral liposomes are poor activators of complement (88,90).

Complement activation via the classical pathway by anionic liposomes has been reported to occur through antibody-independent binding of positively charged C1q to the surface of the DDS through electrostatic interactions (84,91). However, a recent study showed that the structure of the negatively charged moieties on the liposomes, rather than the negative charge per se, is crucial for complement activation (92). Complement activation by PEGylated liposomes has been reported to require the presence of negatively charged compounds such as PEG-phosphatidyl ethanolamine and is possibly initiated by naturally circulating anti-PEG antibodies or in an antibody independent fashion (7,90,93).

Besides liposomes, isobutylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles have been reported to activate complement in vitro. Surface modification of these particles by coating with a high-density (‘brush’ conformation) layer of chitosan or dextran reduced complement activation, whereas a low-density (‘mushroom’ conformation) layer did not (94). In the same study dextran sulfate layers were found to be poor activators of complement, but at the same time promoted the adsorption of serum proteins. Various other charged nanoparticles have been shown to be potent compliment activators in vitro as compared to neutral ones (95–97).

Accelerated Clearance

The clearance of liposomes and other DDS from the blood circulation occurs after recognition by cells belonging to the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) (81,85,98,99). Also hepatocytes seem to play a role in the clearance of liposomes from the blood circulation (100). PEG attached to DDS was initially thought to act as an inert steric barrier for attachment of opsonins, thereby leading to decreased recognition of the DDS by cells of the MPS, resulting in prolonged circulation (34,101). However, it has been shown that after repeated injection PEGylated liposomes are cleared much faster than after the first administration, a phenomenon known as the accelerated blood clearance (ABC) effect (33,35,36,38,42,102–104). The second dose of PEGylated liposomes accumulate mainly in the liver, but also to a lesser extent in the spleen, which implies involvement of Kupffer cells and fixed macrophages of the spleen in the accelerated blood clearance of subsequent doses (105–108).

The ABC effect can be divided into two phases: the induction phase, following the first injection and resulting in formation of serum factors, and the effectuation phase, following the second or subsequent injections in which PEGylated liposomes are rapidly cleared (106,107). The effect was reported to be saturable and mediated by a serum factor. It is thought that complement activation, caused by anti-PEG IgM elicited by the first dose, initiates the ABC phenomenon (37,39,104), whereas a direct effect of the liposomes on the intrinsic phagocytic activity of Kupffer cells was excluded (103).

According to Wang et al., induction of the ABC effect is not only determined by the PEG coating but also by the size and surface charge of the first dose of liposomes (104). However, Laverman and coworkers have reported that the ABC effect is a general characteristic of liposomes and does not depend on the presence of PEG or on the liposome size, but is related to lipid dose and dosing interval (106,109). This may suggest that pre-existing anti-lipid antibodies (23) or other serum components are (also) involved in the ABC effect. Early capture of liposomes by these serum components might explain why in general the first part of the concentration—time curve, especially at low liposome doses, is steeper than the following part.

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity reactions triggered by intravenous administration of DDS have been observed in the clinic for liposomal drugs (e.g., Doxil, Daunoxome), emulsions (e.g. taxol formulated in Cremophor EL), and polymeric micelles (e.g. Genexol, taxol formulated in PLA-PEG micelles) (31,110,111). Although the Genexol-mediated reactions were ascribed to intrinsic properties of paclitaxel, they are more likely related to the PLA-PEG micelles used in this formulation to solubilize the drug.

These anaphylactoid reactions are a consequence of activation of the complement system via the classical and/or the alternative pathway, and are called complement activation-related pseudoallergy (CARPA) (31). As opposed to IgE-mediated allergy requiring presensitization, CARPA occurs at first exposure of the DDS and its severeness usually declines after repeated administration (31,108,112–114). It is therefore unlikely that DDS-induced antibody formation plays a role in CARPA, but the involvement of pre-existing antibodies cannot be excluded. CARPA involves anaphylatoxin (C3a and C5a) liberation which causes an increase of inflammatory cells in the blood circulation. The incidence of CARPA varies between 5–45% of patients treated with DDS, which is much higher than classical anaphylactic reactions to drugs, for example penicillin allergy occurs in less than 2% of the treated patients (31). CARPA can induce serious clinical conditions which show cardiovascular, respiratory and cutaneously related symptoms, such as bradycardia, arrhythmia, tachypnea and flushing.

Platelet Activation

Platelets are known as primary actors in hemostasis. In addition, accumulating evidence points to platelets as important players in the innate immune response (115–117). It has been reported that platelets might play a bridging role between innate and adaptive immune response (115), or act as innate inflammatory cells in an immune response (116). Platelets express a variety of receptors, such as FcγR, TLR4 and TLR2, and can secrete several immune-stimulatory products, such as cytokines and chemokines (115,117,118).

Reports about DDS-induced platelet aggregation are conflicting. It has been demonstrated that liposomes are able to induce (119–121) as well as inhibit (122,123) aggregation of platelets. The types of phospholipids in the membrane of the liposomes (124–126) and the surface charge of these vesicles (119–123) seem to play a role in the procoagulatory properties. Platelet aggregation in vitro and rat thrombosis in vivo was reported to be induced by carbon nanoparticles (127), whereas neutral and PEG-coated surfactant-based nanoparticles did not induce platelet activation in vitro (128). Liposomes with a negative surface charge have been reported to increase as well as inhibit platelet aggregation (120–123).

Little is known about the mechanisms of DDS-induced platelet activation (19). One of the signaling molecules that might play a role is the platelet-activating factor (PAF). PAF is a proinflammatory phospholipid secreted by mast cells, monocytes and macrophages. It interacts with the PAF receptor expressed on cells such as platelets, monocytes and eosinophils. This can lead to platelet aggregation and a number of inflammatory effects, such as chemotaxis and degranulation (124,126), as well as anaphylaxis (129,130).

Aggregation of platelets may also be directly enhanced by the presence of immune complexes on the DDS surface. Platelets are able to recognize these immune complexes through their Fc receptor, FcγRIIa. Aggregated platelets stimulate the production of C3a and C5a, factors of the complement system that play a role in CARPA (41).

SUMMARIZING DISCUSSION

We have surveyed the literature showing that usage of DDS can induce antibody formation and other immunological events, which may result in serious clinical consequences, as summarized in Table II. Antibody-mediated accelerated blood clearance leads to reduced therapeutic concentrations of the drug in the blood circulation resulting in a lower bioavailability and efficacy. The opposite can occur via complement-mediated lysis of the DDS, giving rise to burst release. This will result in increased blood concentrations and altered biodistribution of the drug, and thereby higher toxicity. Hypersensitivity reactions as a result of complement activation can induce serious clinical conditions with cardiovascular, respiratory and cutaneous symptoms. Platelet activation can enhance innate and adaptive immune responses, and induce platelet aggregation. The latter could give rise to thrombus formation and thereby obstruction of blood vessels, resulting in life-threatening situations. However, the impact of platelet activation in immunogenicity of DDS is yet unclear and requires further studies.

Although a complete picture of the immunological risk of DDS is currently lacking, a number of risk factors known to affect the immunological safety of DDS have been identified (Table III). Still, clinical data on the immunogenicity of DDS are scarce, probably because only few products have reached the clinical stage and most of these are anticancer drugs. This drug category is unlikely to give strong antibody responses, firstly because immune compromised cancer patients receiving these drugs are unlikely to form antibodies and secondly because cytotoxic drugs have been shown to reduce antibody formation. On the other hand, complement activation induced by liposomal doxorubicin and colloidal taxol formulations is commonly seen.

For DDS containing drugs other than immunosuppressive agents, one should consider the risk for antibody formation in the design of the DDS. Multiple epitope arrays clustered at the surface of DDS form a particular risk factor for immunogenicity and should be avoided if possible. Ligands such as mannose that are recognized by APCs should especially be avoided, except for vaccination purposes (63,131), although data showing enhanced immune responses when used therapeutically are lacking. The particulate character of many DDS makes them prone to be recognized as foreign by immune cells and the complement system. Soluble polymer–drug conjugates seem less likely to induce antibody formation. Although PEG was initially considered to be an immunologically inert polymer, also PEGylated DDS have been shown to induce antibodies and to be involved in complement activation, accelerated clearance and hypersensitivity reactions. So, PEGylation is no guarantee for an immunologically safe DDS.

The route of administration has not been systematically studied but almost certainly has a major influence on the risk of immunological responses. Whereas subcutaneous administration may be the injection route which most easily generates antibodies, complement activation and platelet activation are of particular clinical relevance upon intravenous administration.

Also other factors such as the release kinetics, release mechanism, as well as the stability of the drug and the carrier are likely to play a yet unidentified role in the immunogenicity of DDS. For instance, dependent on the residence time of a DDS, during release and decomposition of the carrier new surface structures will be created which may be more (or less) immunogenic than the intact system. Moreover, labile protein drugs in DDS are susceptible to aggregation (132), which may generate additional risk.

Antibody formation against DDS typically occurs after one or a few administrations, as opposed to antibodies against recombinant human therapeutic proteins which usually show up after chronic treatment (58,59), despite the similar mechanisms thought to be involved. The observed difference in the kinetics of antibody formation could be due to the fact that in DDS the drugs are deliberately concentrated in colloidal carriers, which are known to have immune stimulatory activities and—almost by definition—contain epitope arrays. In contrast, therapeutic proteins normally contain only small amounts of immunogenic impurities such as aggregates and therefore have a much lower probability of eliciting an immune reaction.

In conclusion, apart from all the benefits such as controlled release and drug targeting, DDS can cause immunological events, which may compromise their pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and targeting capability, and thereby their efficacy and safety. Reported immune reactions against DDS include antibody formation, complement activation, and platelet activation, phenomena which may be interrelated as schematically illustrated in Fig. 3. Most of the available literature data relate to liposomal and HPMA-based DDS, but it is very unlikely that other DDS are immunologically inert. As detailed knowledge about the precise characteristics associated with immunogenicity of DDS is lacking and the scarce literature data are in part conflicting, prediction of the immunogenicity of DDS is currently very difficult. Still, some risk factors associated with immunogenicity are known (Table III) and should not be overlooked early in the development of novel DDS. In parallel, further research on the causative factors of immunogenicity of DDS is essential to better permit the rational design of immunologically safe DDS.

References

T. M. Allen and P. R. Cullis. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science. 303:1818–1822 (2004). doi:10.1126/science.1095833.

D. J. Crommelin, G. Storm, W. Jiskoot, R. Stenekes, E. Mastrobattista, and W. E. Hennink. Nanotechnological approaches for the delivery of macromolecules. J. Control Release. 87:81–88 (2003). doi:10.1016/S0168-3659(03)00014-2.

T. Lammers, W. E. Hennink, and G. Storm. Tumour-targeted nanomedicines: principles and practice. Br. J. Cancer. 99:392–397 (2008). doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604483.

E. Mastrobattista, M. A. van der Aa, W. E. Hennink, and D. J. Crommelin. Artificial viruses: a nanotechnological approach to gene delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5:115–121 (2006). doi:10.1038/nrd1960.

A. Prokop and J. M. Davidson. Nanovehicular intracellular delivery systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 97:3518–3590 (2008). doi:10.1002/jps.21270.

R. C. Mundargi, V. R. Babu, V. Rangaswamy, P. Patel, and T. M. Aminabhavi. Nano/micro technologies for delivering macromolecular therapeutics using poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) and its derivatives. J. Control Release. 125:193–209 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.013.

S. M. Moghimi and I. Hamad. Liposome-mediated triggering of complement cascade. J. Liposome Res. 18:195–209 (2008). doi:10.1080/08982100802309552.

T. Lian and R. J. Ho. Trends and developments in liposome drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 90:667–680 (2001). doi:10.1002/jps.1023.

D. J. Crommelin and G. Storm. Liposomes: from the bench to the bed. J. Liposome Res. 13:33–36 (2003). doi:10.1081/LPR-120017488.

M. Jelinkova, J. Strohalm, T. Etrych, K. Ulbrich, and B. Rihova. Starlike vs. classic macromolecular prodrugs: two different antibody-targeted HPMA copolymers of doxorubicin studied in vitro and in vivo as potential anticancer drugs. Pharm. Res. 20:1558–1564 (2003). doi:10.1023/A:1026170830782.

B. Rihova, J. Strohalm, M. Kovar, T. Mrkvan, V. Subr, O. Hovorka, M. Sirova, L. Rozprimova, K. Kubackova, and K. Ulbrich. Induction of systemic antitumour resistance with targeted polymers. Scand. J. Immunol. 62(Suppl 1):100–105 (2005). doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01617.x.

D. T. O’Hagan and N. M. Valiante. Recent advances in the discovery and delivery of vaccine adjuvants. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2:727–735 (2003). doi:10.1038/nrd1176.

D. T. O’Hagan and R. Rappuoli. Novel approaches to vaccine delivery. Pharm. Res. 21:1519–1530 (2004). doi:10.1023/B:PHAM.0000041443.17935.33.

M. Singh, A. Chakrapani, and D. O’Hagan. Nanoparticles and microparticles as vaccine-delivery systems. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 6:797–808 (2007). doi:10.1586/14760584.6.5.797.

C. E. Astete and C. M. Sabiov. Synthesis and characterization of PLGA nanoparticles. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 17:247–289 (2006). doi:10.1163/156856206775997322.

T. M. Fahmy, P. M. Fong, J. Park, T. Constable, and W. M. Saltzman. Nanosystems for simultaneous imaging and drug delivery to T cells. AAPS Journal. 9:E171–E180 (2007). doi:10.1208/aapsj0902019.

J. Kopeček, P. Kopečková, T. Minko, and Z.-R. Lu. HPMA copolymer-anticancer drug conjugates: design, activity, and mechanism of action. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 50:61–81 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0939-6411(00)00075-8.

F. Alexis, E. Pridgen, L. K. Molnar, and O. C. Farokhzad. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol. Pharmacol. 5:505–515 (2008). doi:10.1021/mp800051m.

M. A. Dobrovolskaia, P. Aggarwal, J. B. Hall, and S. E. McNeil. Preclinical studies to understand nanoparticle interaction with the immune system and its potential effects on nanoparticle biodistribution. Mol. Pharmacol. 5:487–495 (2008). doi:10.1021/mp800032f.

M. A. Dobrovolskaia and S. E. McNeil. Immunological properties of engineered nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2:469–478 (2007). doi:10.1038/nnano.2007.223.

S. M. Moghimi, A. C. Hunter, and J. C. Murray. Long-circulating and target-specific nanoparticles: theory to practice. Pharmacol. Rev. 53:283–318 (2001).

B. Romberg, W. E. Hennink, and G. Storm. Sheddable coatings for long-circulating nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 25:55–71 (2008). doi:10.1007/s11095-007-9348-7.

C. R. Alving. Antibodies to lipids and liposomes: immunology and safety. J. Liposome Res. 16:157–166 (2006). doi:10.1080/08982100600848553.

C. R. Alving, G. M. Swartz Jr., N. M. Wassef, J. L. Ribas, E. E. Herderick, R. Virmani, F. D. Kolodgie, G. R. Matyas, and J. F. Cornhill. Immunization with cholesterol-rich liposomes induces anti-cholesterol antibodies and reduces diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and plaque formation. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 127:40–49 (1996). doi:10.1016/S0022-2143(96)90164-X.

B. G. Schuster, M. Neidig, B. M. Alving, and C. R. Alving. Production of antibodies against phosphocholine, phosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin, and lipid A by injection of liposomes containing lipid A. J. Immunol. 122:900–905 (1979).

G. M. Swartz Jr., M. K. Gentry, L. M. Amende, E. J. Blanchette-Mackie, and C. R. Alving. Antibodies to cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U. S. A. 85:1902–1906 (1988). doi:10.1073/pnas.85.6.1902.

C. R. Alving and G. M. Swartz Jr. Antibodies to cholesterol, cholesterol conjugates and liposomes: implications for atherosclerosis and autoimmunity. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 10:441–453 (1991).

C. R. Alving, N. M. Wassef, and M. Potter. Antibodies to cholesterol: biological implications of antibodies to lipids. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 210:181–186 (1996).

B. Banerji and C. R. Alving. Anti-liposome antibodies induced by lipid A. J. Immunol. 1216:1080–1084 (1981).

N. Karasavvas, Z. Beck, J. Tong, G. R. Matyas, M. Rao, F. E. McCutchan, N. L. Michael, and C. R. Alving. Antibodies induced by liposomal protein exhibit dual binding to protein and lipid epitopes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 366:982–987 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.057.

J. Szebeni. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: a new class of drug-induced acute immune toxicity. Toxicology. 216:106–121 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.023.

D. E. Owens 3rd, and N. A. Peppas. Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 307:93–102 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.010.

T. Ishida, K. Atobe, X. Y. Wang, and H. Kiwada. Accelerated blood clearance of PEGylated liposomes upon repeated injections: effect of doxorubicin-encapsulation and high-dose first injection. J. Control. Release. 115:251–258 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.08.017.

T. Ishida, M. Ichihara, X. Y. Wang, and H. Kiwada. Spleen plays an important role in the induction of accelerated blood clearance of PEGylated liposomes. J. Control. Release. 115:243–250 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.08.001.

T. Ishida, M. Ichihara, X. Y. Wang, K. Yamamoto, J. Kimura, E. Majima, and H. Kiwada. Injection of PEGylated liposomes in rats elicts PEG-specific IgM, which is responsible for rapid elimination of a second dose of PEGylated liposomes. J. Control. Release. 112:15–25 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.005.

T. Ishida, X. Y. Wang, T. Shimizu, K. Nawata, and H. Kiwada. PEGylated liposomes elicit an anti-PEG IgM response in a T-cell independent manner. J. Control. Release. 122:349–355 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.015.

S. C. Semple, T. O. Harasym, K. A. Clow, S. M. Ansell, S. K. Klimuk, and M. J. Hope. Immunogenicity and rapid blood clearance of liposomes containing polyethylene glycol-lipid conjugates and nucleic Acid. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 312:1020–1026 (2005). doi:10.1124/jpet.104.078113.

X. Y. Wang, T. Ishida, and H. Kiwada. Anti-PEG IgM elicted by injection of liposomes is involved in the enhanced blood clearance of a subsequent dose of PEGylated liposomes. J. Control. Release. 119:236–244 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.02.010.

K. Środa, J. Rydlewski, M. Lnagner, A. Kozubek, M. Grzybek, and A. F. Sikorski. Repeated injections of PEG-PE liposomes generate anti-PEG antibodies. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 10:37–47 (2005).

Q. Vos, A. Lees, Z. Q. Wu, C. M. Snapper, and J. J. Mond. B-cell activation by T-cell-independent type 2 antigens as an integral part of the humoral immune response to pathogenic microorganisms. Immunol. Rev. 176:154–170 (2000). doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2000.00607.x.

D. Male, J. Brostoff, D. B. Roth, and I. Roitt. Immunology. Seventh edition, Mosby-Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2006.

J. K. Armstrong, G. Hempel, S. Koling, L. S. Chan, T. Fisher, H. J. Meiselman, and G. Garratty. Antibody against poly(ethylene glycol) adversely affects PEG-asparaginase therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Cancer. 110:103–111 (2007). doi:10.1002/cncr.22739.

N. J. Ganson, S. J. Kelly, E. Scarlett, J. S. Sundy, and M. S. Hershfield. Control of hyperuricemia in subjects with refractory gout, and induction of antibody against poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), in a phase I trial of subcutaneous PEGylated urate oxidase. Arthritis Res. Ther. 8:R12 (2006). doi:10.1186/ar1861.

B. Rihova, K. Ulbrich, J. Kopecek, and P. Mancal. Immunogenicity of N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-methacrylamide copolymers—potential hapten or drug carriers. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 28:217–227 (1983). doi:10.1007/BF02884085.

B. Říhová. Immunomodulating activities of soluble synthetic polymer-bound drugs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 54:653–674 (2002). doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00043-1.

P. R. Hart, P. Kopeckova, V. Omelyanenko, E. Enioutina, and J. Kopecek. HPMA copolymer-modified avidin: immune response. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 11:1–12 (2000). doi:10.1163/156856200743454.

P. Artursson, I. L. Mårtensson, and I. Sjöholm. Biodegradable microspheres. III: some immunological properties of polyacryl starch microparticles. J. Pharm. Sci. 75:697–701 (1986). doi:10.1002/jps.2600750717.

A. Klopstock, M. Pinto, and A. Rimon. Antibodies reacting with steroid haptens. J. Immunol. 92:515–519 (1964).

J. Chesham and G. E. Davies. The role of metabolism in the immunogenicity of drugs: production of antibodies to a horseradish peroxidase generated conjugate paracetamol. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 61:224–231 (1985).

H. M. Dintzis, R. Z. Dintzis, and B. Vogelstein. Molecular determinants of immunogenicity: the immunon model of immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73:3671–3675 (1976). doi:10.1073/pnas.73.10.3671.

R. Z. Dintzis, M. Okajima, M. H. Middleton, G. Greene, and H. M. Dintzis. The immunogenicity of soluble haptenated polymers is determined by molecular mass and hapten valence. J. Immunol. 143:1239–1244 (1989).

B. Sulzer and A. S. Perelson. Immunons revisited: binding of multivalent antigens to B cells. Mol. Immunol. 34:63–74 (1997). doi:10.1016/S0161-5890(96)00096-X.

J. J. Mond, K. E. Stein, B. Subbarao, and W. E. Paul. Analysis of B cell activation requirements with TNP-conjugated polyacrylamide beads. J. Immunol. 123:239–245 (1979).

M. L. Freimer, K. McIntosh, R. A. Adams, C. R. Alving, and D. B. Drachman. Gangliosides elicit a T-cell independent antibody response. J. Autoimmun. 6:281–289 (1993). doi:10.1006/jaut.1993.1024.

G. R. Matyas, N. M. Wassef, M. Rao, and C. R. Alving. Induction and detection of antibodies to squalene. J. Immunol. Methods. 245:1–14 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00268-4.

J. H. Eldridge, J. K. Staas, J. A. Meulbroek, T. R. Tice, and R. M. Gilley. Biodegradable and biocompatible poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres as an adjuvant for staphylococcal enterotoxin B toxoid which enhances the level of toxin-neutralizing antibodies. Infect. Immun. 59:2978–2986 (1991).

P. G. Tardi, E. N. Swartz, T. O. Harasym, P. R. Cullis, and M. B. Bally. An immune response to ovalbumin covalently coupled to liposomes is prevented when the liposomes used contain doxorubicin. J. Immunol. Methods. 210:137–148 (1997). doi:10.1016/S0022-1759(97)00178-6.

S. Hermeling, D. J. A. Crommelin, H. Schellekens, and W. Jiskoot. Structure-immunogenicity relationships of therapeutic proteins. Pharm. Res. 21:897–903 (2004). doi:10.1023/B:PHAM.0000029275.41323.a6.

H. Schellekens. Bioequivalence and the immunogenicity of biopharmaceuticals. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1:457–462 (2002). doi:10.1038/nrd818.

K. Ramani, R. D. Miclea, V. S. Purohit, D. E. Mager, R. M. Straubinger, and S. V. Balu-Iyer. Phosphatidylserine containing liposomes reduce immunogenicity of recombinant human factor VIII (rFVIII) in a murine model of hemophilia A. J. Pharm. Sci. 97:1386–1398 (2008). doi:10.1002/jps.21102.

P. R. Hoffmann, J. A. Kench, A. Vondracek, E. Kruk, D. L. Daleke, M. Jordan, P. Marrack, P. M. Henson, and V. A. Fadok. Interaction between phosphatidylserine and the phosphatidylserine receptor inhibits immune responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 174:1393–1404 (2005).

K. Ramani, V. Purohit, R. Miclea, P. Gaitonde, R. M. Straubinger, and S. V. Balu-Iyer. Passive transfer of polyethylene glycol to liposomal-recombinant human FVIII enhances its efficacy in a murine model for hemophilia A. J. Pharm. Sci. 97:3753–3764 (2008). doi:10.1002/jps.21266.

J. M. Irache, H. H. Salman, C. Gamazo, and S. Espuelas. Mannose-targeted systems for the delivery of therapeutics. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 5:703–724 (2008). doi:10.1517/17425247.5.6.703.

N. C. Phillips and J. Dahman. Immunogenicity of immunoliposomes: reactivity against species-specific IgG and liposomal phospholipids. Immunol. Lett. 45:149–152 (1995). doi:10.1016/0165-2478(94)00251-L.

J. A. Harding, C. M. Engbers, M. S. Newman, N. I. Goldstein, and S. Zalipsky. Immunogenicity and pharmacokinetic attributes of poly (ethylene glycole)-grafted immunoliposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1327:181–192 (1997). doi:10.1016/S0005-2736(97)00056-4.

B. X. Chen, S. R. Wilson, M. Das, D. J. Coughlin, and B. F. Erlanger. Antigenicity of fullerenes: antibodies specific for fullerenes and their characteristics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:10809–10813 (1998). doi:10.1073/pnas.95.18.10809.

M. F. Bachmann and R. M. Zinkernagel. Neutralizing antiviral B cell responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:235–270 (1997). doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.235.

J. J. Mond, Q. Vos, A. Lees, and C. M. Snapper. T cell independent antigens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7:349–354 (1995). doi:10.1016/0952-7915(95)80109-X.

M. F. Bachmann, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. T helper cell-independent neutralizing B cell response against vesicular stomatitis virus: role of antigen patterns in B cell induction? Eur. J. Immunol. 25:3445–3451 (1995). doi:10.1002/eji.1830251236.

M. F. Bachmann, U. H. Rohrer, T. M. Kundig, K. Burki, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. The influence of antigen organization on B cell responsiveness. Science. 262:1448–1451 (1993). doi:10.1126/science.8248784.

M. F. Bachmann and R. M. Zinkernagel. The influence of virus structure on antibody responses and virus serotype formation. Immunol. Today. 17:553–558 (1996). doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(96)10066-9.

B. Chackerian, P. Lenz, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. Determinants of autoantibody induction by conjugated papillomavirus virus-like particles. J. Immunol. 169:6120–6126 (2002).

B. Chackerian, D. R. Lowy, and J. T. Schiller. Conjugation of a self-antigen to papillomavirus-like particles allows for efficient induction of protective autoantibodies. J. Clin. Invest. 108:415–423 (2001).

M. Brunswick, F. D. Finkelman, P. F. Highet, J. K. Inman, H. M. Dintzis, and J. J. Mond. Picogram quantities of anti-Ig antibodies coupled to dextran induce B cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 140:3364–3372 (1988).

L. M. Pecanha, C. M. Snapper, F. D. Finkelman, and J. J. Mond. Dextran-conjugated anti-Ig antibodies as a model for T cell-independent type 2 antigen-mediated stimulation of Ig secretion in vitro. I. Lymphokine dependence. J. Immunol. 146:833–839 (1991).

S. Akira and K. Takeda. Functions of toll-like receptors: lessons from KO mice. C. R. Biol. 327:581–589 (2004). doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2004.04.002.

J. Szebeni. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy caused by amphiphilic drug carriers: the role of lipoproteins. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2:443–449 (2005). doi:10.2174/156720105774370212.

J. Parkin and B. Cohen. An overview of the immune system. Lancet. 357:1777–1789 (2001). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04904-7.

T. Ishida, H. Harashima, and H. Kiwada. Liposome clearance. Biosci. Rep. 22:197–224 (2002). doi:10.1023/A:1020134521778.

P. Parham. The Immune System, Garland Publishing/Elsevier Science Ltd, New York, 2000.

X. Yan, G. L. Scherphof, and J. A. A. M. Kamps. Liposome opsonization. J. Liposome Res. 15:109–139 (2005).

K. Funato, R. Yoda, and H. Kiwada. Contribution of complement system on destabilization of liposomes composed of hydrogenated egg phosphatidylcholine in rat fresh plasma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1103:198–204 (1992). doi:10.1016/0005-2736(92)90087-3.

D. L. Gordon, J. Rice, J. J. Finlay-Jones, P. J. McDonald, and M. K. Hostetter. Analysis of C3 deposition and degradation on bacterial surfaces after opsonization. J. Infect. Dis. 157:697–704 (1988).

A. J. Bradley, E. Maurer-Spurej, D. E. Brooks, and D. V. Devine. Unusual electrostatic effects on binding of C1q to anionic liposomes: Role of anionic phospholipid domains and their line tension. Biochemistry. 38:8112–8123 (1999). doi:10.1021/bi990480a.

D. V. Devine and J. M. Marjan. The role of immunoproteins in the survival of liposomes in the circulation. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 14:105–131 (1997).

J. Szebeni, N. M. Wassef, A. S. Rudolph, and C. R. Alving. Complement activation in human serum by liposome-encapsulated hemoglobin: the role of natural anti-phospholipid antibodies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1285:127–130 (1996). doi:10.1016/S0005-2736(96)00201-5.

C. R. Alving, R. L. Richards, and A. A. Guirguis. Cholesterol-dependent human complement activation resulting in damage to liposomal model membranes. J. Immunol. 118:342–347 (1977).

A. Chonn, P. R. Cullis, and D. V. Devine. The role of surface charge in the activation of the classical and alternative pathways of complement by liposomes. J. Immunol. 146:4234–4241 (1991).

C. M. Cunningham, M. Kingzette, R. L. Richards, C. R. Alving, T. F. Lint, and H. Gewurz. Activation of human complement by liposomes: a model for membrane activation of the alernative pathway. J. Immunol. 122:1237–1242 (1979).

S. M. Moghimi, I. Hamad, T. L. Andresen, K. Jorgensen, and J. Szebeni. Methylation of the phosphate oxygen moiety of phospholipid-methoxy(polyethylene glycol) conjugate prevents PEGylated liposome-mediated complement activation and anaphylatoxin production. FASEB J. 20:2591–2593 (2006). doi:10.1096/fj.06-6186fje.

T. Kovacsovics, J. Tschopp, A. Kress, and H. Isliker. Antibody-indepent activation of C1, the first component of complement, by cardiolipin. J Immunol. 135:2695–2700 (1985).

K. Sou and E. Tsuchida. Electrostatic interactions and complement activation on the surface of phospholipid vesicle containing acidic lipids: effect of the structure of acidic groups. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1778:1035–1041 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.01.006.

J. Szebeni, L. Baranyi, S. Savay, J. Milosevits, R. Bunger, P. Laverman, J. M. Metselaar, G. Storm, A. Chanan-Khan, L. Liebes, F. M. Muggia, R. Cohen, Y. Barenholz, and C. R. Alving. Role of complement activation in hypersensitivity reactions to doxil and hynic PEG liposomes: experimental and clinical studies. J. Liposome Res. 12:165–172 (2002). doi:10.1081/LPR-120004790.

I. Bertholon, C. Vauthier, and D. Labarre. Complement activation by core-shell poly(isobutylcyanoacrylate)-polysaccharide nanoparticles: influences of surface morphology, length, and type of polysaccharide. Pharm. Res. 23:1313–1323 (2006). doi:10.1007/s11095-006-0069-0.

D. W. Bartlett and M. E. Davis. Physicochemical and biological characterization of targeted, nucleic acid-containing nanoparticles. Bioconjug. Chem. 18:456–468 (2007). doi:10.1021/bc0603539.

S. Nagayama, K. Ogawara, Y. Fukuoka, K. Higaki, and T. Kimura. Time-dependent changes in opsonin amount associated on nanoparticles alter their hepatic uptake characteristics. Int. J. Pharm. 342:215–221 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.04.036.

A. Vonarbourg, C. Passirani, P. Saulnier, P. Simard, J. C. Leroux, and J. P. Benoit. Evaluation of pegylated lipid nanocapsules versus complement system activation and macrophage uptake. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 78:620–628 (2006). doi:10.1002/jbm.a.30711.

H. Patel. Serum opsonins and liposomes: their interaction and opsonophagocytosis. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 9:39–90 (1992).

S. M. Moghimi and H. M. Patel. Serum-mediated recognition of liposomes by phagocytic cells of the reticuloendothelial system—The concept of tissue specificity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 32:45–60 (1998). doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(97)00131-2.

G. L. Scherphof and J. A. A. M. Kamps. The role of hepatocytes in the clearance of liposomes from the blood circulation. Prog. Lipid Res. 40:149–166 (2001). doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(00)00020-5.

J. Senior, C. Delgado, D. Fisher, C. Tilcock, and G. Gegoriadis. Influence of surface hydrophilicity of liposomes on their interaction with plasma protein and clearance from the circulation: studies with poly(ethylene glycol)-coated vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1062:77–82 (1991). doi:10.1016/0005-2736(91)90337-8.

T. Ishida, M. Harada, X. Y. Wang, M. Ichihara, K. Irimura, and H. Iwada. Accelerated blood clearance of PEGylated liposimes following preceding injection: Effects of lipid dose and PEG surface density and chain length of the first-dose liposomes. J. Control. Release. 105:305–317 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.04.003.

T. Ishida, S. Kashima, and H. Kiwada. The contribution of phagocytic activity of liver macrophages to the accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon of PEGylated liposomes in rats. J. Control. Release. 126:162–165 (2008).

X. Y. Wang, T. Ishida, M. Ichihara, and H. Kiwada. Influence of the physicochemical properties of liposomes on the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon in rats. J. Control. Release. 104:91–102 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.01.008.

T. M. Allen. Toxicity of drug carriers to the mononuclear phagocyte system. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2:55–67 (1988). doi:10.1016/0169-409X(88)90005-1.

P. Laverman, M. G. Carstens, O. C. Boerman, E. T. M. Dams, W. J. G. Oyen, N. V. Rooijen, F. H. M. Corstens, and G. Storm. Factors affecting the accelerated blood clearance of polyethylene glycol-liposomes upon repeated injection. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298:607–612 (2001).

P. Laverman, O. C. Boerman, W. J. G. Oyen, F. H. M. Corstens, and G. Storm. In vivo applications of PEG liposomes: unexpected observations. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 18:551–566 (2001).

A. Judge, K. McClintock, J. Phelps, and I. Maclachlan. Hypersensitivity and loss of disease site targeting caused by antibody responses to PEGylated liposomes. Mol. Ther. 13:328–337 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.014.

M. G. Carstens, B. Romberg, P. Laverman, O. C. Boerman, C. Oussoren, and G. Storm. Observations on the disappearance of the stealth property of PEGylated liposomes. Effect of lipid dose and dosing frequency. Liposome Technology. 3:79–93 (2006).

D. W. Kim, S. Y. Kim, H. K. Kim, S. W. Kim, S. W. Shin, J. S. Kim, K. Park, M. Y. Lee, and D. S. Heo. Multicenter phase II trial of Genexol-PM, a novel Cremophor-free, polymeric micelle formulation of paclitaxel, with cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 18:2009–2014 (2007). doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm374.

K. S. Lee, H. C. Chung, S. A. Im, Y. H. Park, C. S. Kim, S. B. Kim, S. Y. Rha, M. Y. Lee, and J. Ro. Multicenter phase II trial of Genexol-PM, a Cremophor-free, polymeric micelle formulation of paclitaxel, in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 108:241–250 (2008). doi:10.1007/s10549-007-9591-y.

J. Szebeni, C. R. Alving, L. Rosivall, R. Bünger, L. Barabyi, P. Bedöcs, M. Tóth, and Y. Barenholz. Animal models of complement-mediates hypersensitivity reactions to liposomes and other lipid-based nanoparticles. J. Liposome Res. 17:107–117 (2007). doi:10.1080/08982100701375118.

J. Szebeni, J. L. Fontana, N. M. Wassef, P. D. Mongan, D. S. Morse, D. E. Dobbins, G. L. Stahl, R. Bünger, and C. R. Alving. Hemodynamic changes induced by liposomes and liposome-encapsulated hemoglobin in pigs a model for pseudoallergic cardiopulmonary reactions to liposomes: Role of complement and inhibition by soluble CR1 and anti-C5a antibody. Circulation. 99:2302–2309 (1999).

A. Chanan-Khan, J. Szebeni, S. Savay, L. Liebes, N. M. Rafique, C. R. Alving, and F. M. Muggia. Complement activation following first exposure to pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): possible role in hypersensitivity reactions. Ann. Oncol. 14:1430–1437 (2003). doi:10.1093/annonc/mdg374.

F. Cognasse, J. W. Semple, and O. Gerraud. Platelets as potential immunomodulators: is there a role for platelet Toll-like receptors. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 3:109–115 (2007). doi:10.2174/157339507780655522.

S. C. Pitchford. Novel uses for anti-platelet agents as anti-inflammatory drugs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 152:987–1002 (2007). doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707364.

B. E. Kehrel and K. Jurk. Platelets at the interface between hemostasis and innate immunity. Transfusion Med. Hemother. 31:379–386 (2004). doi:10.1159/000082482.

P. V. Hundelshausen and C. Weber. Platelets as immune cells: Bridging inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 100:27–40 (2007). doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000252802.25497.b7.

H. C. Loughrey, M. B. Bally, L. W. Reinish, and P. R. Cullis. The binding of phosphatidylglycerol liposomes to rat platelets is mediated by complement. Thromb. Haemost. 64:172–176 (1990).

G. Zbinden, H. Wunderli-Allenspach, and L. Grimm. Assessment of thrombogenic potential of liposomes. Toxicology. 54:273–280 (1989). doi:10.1016/0300-483X(89)90063-2.

M. J. Parnham and H. Wetzig. Toxicity screening of liposomes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 64:263–274 (1993).

V. R. Berdichevskii, R. A. Markosyan, E. Y. Pozin, V. N. Smirnov, A. V. Suvorov, V. P. Torchilin, and E. I. Chazov. Effect of liposomes on platelet function. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 88:828–831 (1979). doi:10.1007/BF00869205.

V. I. Zakrevskii, I. A. Rud’ko, and A. A. Kubatiev. Effect of negatively charged liposomes on ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 114:1590–1593 (1992). doi:10.1007/BF00837645.

V. Kumar, A. K. Abbas, and N. Fausto. Pathologic Basis of Disease. Seventh edition, Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2005.

H. C. C. F. Neto, D. M. Stafforini, S. M. Prescott, and G. A. Zimmerman. Regulating inflammation through the anti-inflammatory enzyme platelet-activating factor-acetylhydrolase. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 100:83–91 (2005).

S. D. Shuklu. Platelet-activation factor receptor and signal transduction mechanism. FASEB J. 6:2296–2301 (1992).

A. Radomski, P. Jurasz, D. Alonso-Escolano, M. Drews, M. Morandi, T. Malinski, and M. W. Radomski. Nanoparticle-induced platelet aggregation and vascular thrombosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 146:882–893 (2005). doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706386.

J. M. Koziara, J. J. Oh, W. S. Akers, S. P. Ferraris, and R. J. Mumper. Blood compatibility of cetyl alcohol/polysorbate-based nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 22:1821–1828 (2005). doi:10.1007/s11095-005-7547-7.

F. D. Finkelman. Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120:506–515; 516–507 (2007), quiz .

P. Vadas, M. Gold, B. Perelman, G. M. Liss, G. Lack, T. Blyth, F. E. Simons, K. J. Simons, D. Cass, and J. Yeung. Platelet-activating factor, PAF acetylhydrolase, and severe anaphylaxis. N. Engl. J. Med. 358:28–35 (2008). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070030.

C. Arigita, L. Bevaart, L. A. Everse, G. A. Koning, W. E. Hennink, D. J. Crommelin, J. G. van de Winkel, M. J. van Vugt, G. F. Kersten, and W. Jiskoot. Liposomal meningococcal B vaccination: role of dendritic cell targeting in the development of a protective immune response. Infect. Immun. 71:5210–5218 (2003). doi:10.1128/IAI.71.9.5210-5218.2003.

M. van de Weert, W. E. Hennink, and W. Jiskoot. Protein instability in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles. Pharm. Res. 17:1159–1167 (2000). doi:10.1023/A:1026498209874.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiskoot, W., van Schie, R.M.F., Carstens, M.G. et al. Immunological Risk of Injectable Drug Delivery Systems. Pharm Res 26, 1303–1314 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-009-9855-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-009-9855-9