Abstract

Purpose

To study the effect of sequentially changing the chain length, oxidation level, and charge distribution in N 4,N 9-diacyl and N 4,N 9-dialkyl spermines on siRNA formulation, and then to compare their lipoplex transfection efficiency in cell lines.

Methods

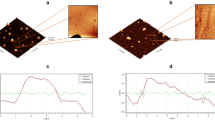

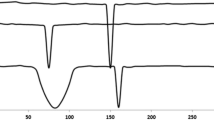

Eight N 4,N 9-diacyl polyamines: N 4,N 9-[didecanoyl, dilauroyl, dimyristoyl, dimyristoleoyl, dipalmitoyl, distearoyl, dioleoyl and diretinoyl]-1,12-diamino-4,9-diazadodecane were synthesized. Their abilities to bind to siRNA and form nanoparticles were studied using a RiboGreen intercalation assay and particle sizing. Two diamides were also reduced to afford tetraamines N 4,N 9-distearyl- and N 4,N 9-dioleyl-1,12-diamino-4,9-diazadodecane. Delivery of fluorescein-labelled Label IT® RNAi Delivery Control was studied in FEK4 primary skin cells and in an immortalized cancer cell line (HtTA), and compared with TransIT-TKO.

Results

The design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship studies of a series of N 4,N 9-disubstituted spermines as efficient vectors for non-viral siRNA delivery to primary skin and cancer cell lines is reported. These non-liposomal cationic lipids are promising siRNA carriers based on the naturally occurring polyamine spermine showing that C-18 is a better chain length as shorter chains are more toxic.

Conclusions

N 4,N 9-Distearoyl spermine and N 4,N 9-dioleoyl spermine are efficient siRNA formulation and delivery vectors, even in the presence of serum, comparable to TransIT-TKO. However, four positive charges distributed as in spermine was significantly more toxic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- EMEM:

-

Earle’s Minimal Essential Medium

- FCS:

-

foetal calf serum

- HRMS:

-

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

References

I. S. Blagbrough, and H. M. Ghonaim. Polyamines and their conjugates for gene and siRNA delivery. In G. Dandrifosse (ed.), Biological aspects of biogenic amines, polyamines and polyamine conjugates, Research Signpost, India, 2008 in press.

K. Aoki, S. Furuhata, K. Hatanaka, M. Maeda, J. S. Remy, J. P. Behr, M. Terada, and T. Yoshida. Polyethylenimine-mediated gene transfer into pancreatic tumor dissemination in the murine peritoneal cavity. Gene Ther. 8:508–514 (2001). doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3301435.

G. Dolivet, J. L. Merlin, M. Barberi-Heyob, C. Ramacci, P. Erbacher, R. M. Parache, J. P. Behr, and F. Guillemin. In vivo growth inhibitory effect of iterative wild-type p53 gene transfer in human head and neck carcinoma xenografts using glucosylated polyethylenimine nonviral vector. Cancer Gene Ther. 9:708–714 (2002). doi:10.1038/sj.cgt.7700485.

S. Ferrari, A. Pettenazzo, N. Garbati, F. Zacchello, J. P. Behr, and M. Scarpa. Polyethylenimine shows properties of interest for cystic fibrosis gene therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gene Struct. Expression. 1447:219–225 (1999).

F. E. Ruiz, J. P. Clancy, M. A. Perricone, Z. Bebok, J. S. Hong, S. H. Cheng, D. P. Meeker, K. R. Young, R. A. Schoumacher, M. R. Weatherly, L. Wing, J. E. Morris, L. Sindel, M. Rosenberg, F. W. van Ginkel, J. R. Mcghee, D. Kelly, R. K. Lyrene, and E. J. Sorscher. A clinical inflammatory syndrome attributable to aerosolized lipid-DNA administration in cystic fibrosis. Hum. Gene Ther. 12:751–761 (2001). doi:10.1089/104303401750148667.

T. A. Rando. Non-viral gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: progress and challenges. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 1772:263–271 (2007).

I. S. Blagbrough, E. Moya, and S. Taylor. Polyamines and polyamine amides from wasps and spiders. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 22:888–893 (1994).

I. S. Blagbrough, A. J. Geall, and S. A. David. Lipopolyamines incorporating the tetraamine spermine, bound to an alkyl chain, sequester bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Letters. 10:1959–1962 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00380-2.

J. G. Delcros, S. Tomasi, S. Carrington, B. Martin, J. Renault, I. S. Blagbrough, and P. Uriac. Effect of spermine conjugation on the cytotoxicity and cellular transport of acridine. J. Med. Chem. 45:5098–5111 (2002). doi:10.1021/jm020843w.

I. S. Blagbrough, A. J. Geall, and A. P. Neal. Polyamines and novel polyamine conjugates interact with DNA in ways that can be exploited in non-viral gene therapy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:397–406 (2003). doi:10.1042/BST0310397.

J. P. Behr, B. Demeneix, J. P. Loeffler, and J. P. Mutul. Efficient gene-transfer into mammalian primary endocrine-cells with lipopolyamine-coated DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:6982–6986 (1989). doi:10.1073/pnas.86.18.6982.

O. A. A. Ahmed, N. Adjimatera, C. Pourzand, and I. S. Blagbrough. N 4,N 9-Dioleoyl spermine is a novel nonviral lipopolyamine vector for plasmid DNA formulation. Pharm. Res. 22:972–980 (2005). doi:10.1007/s11095-005-4592-1.

N. Adjimatera, T. Kral, M. Hof, and I. S. Blagbrough. Lipopolyamine-mediated single nanoparticle formation of calf thymus DNA analyzed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Pharm. Res. 23:1564–1573 (2006). doi:10.1007/s11095-006-0278-6.

O. A. A. Ahmed, C. Pourzand, and I. S. Blagbrough. Varying the unsaturation in N 4,N 9-dioctadecanoyl spermines: Nonviral lipopolyamine vectors for more efficient plasmid DNA formulation. Pharm. Res. 23:31–40 (2006). doi:10.1007/s11095-005-8717-3.

D. McLaggan, N. Adjimatera, K. Sepcic, M. Jaspars, D. J. MacEwan, I. S. Blagbrough, and R. H. Scott. Pore forming polyalkylpyridinium salts from marine sponges versus synthetic lipofection systems: distinct tools for intracellular delivery of cDNA and siRNA. BMC Biotechnol. 6:6 (2006). doi:10.1186/1472-6750-6-6.

R. G. Crystal. Transfer of genes to humans: early lessons and hurdles to success. Science. 270:404–410 (1995). doi:10.1126/science.270.5235.404.

P. Kreiss, B. Cameron, R. Rangara, P. Mailhe, O. Guerre-Charriol, M. Airiau, D. Scherman, J. Crouzet, and B. Pitard. Plasmid DNA size does not affect the physicochemical properties of lipoplexes but modulates gene transfer efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3792–3798 (1999). doi:10.1093/nar/27.19.3792.

G. de Jong, A. Telenius, S. Vanderbyl, A. Meitz, and J. Drayer. Efficient in-vitro transfer of a 60-Mb mammalian artificial chromosome into murine and hamster cells using cationic lipids and dendrimers. Chromosome Res. 9:475–485 (2001). doi:10.1023/A:1011680529073.

S. W. Dow, L. G. Fradkin, D. H. Liggitt, A. P. Willson, T. D. Heath, and T. A. Potter. Lipid-DNA complexes induce potent activation of innate immune responses and antitumor activity when administered intravenously. J. Immunol. 163:1552–1561 (1999).

M. Whitmore, S. Li, and L. Huang. LPD lipopolyplex initiates a potent cytokine response and inhibits tumor growth. Gene Ther. 6:1867–1875 (1999). doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3301026.

M. M. Whitmore, S. Li, L. Falo, and L. Huang. Systemic administration of LPD prepared with CpG oligonucleotides inhibits the growth of established pulmonary metastases by stimulating innate and acquired antitumor immune responses. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 50:503–514 (2001). doi:10.1007/s002620100227.

A. Fire, S. Q. Xu, M. K. Montgomery, S. A. Kostas, S. E. Driver, and C. C. Mello. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 391:806–811 (1998). doi:10.1038/35888.

S. M. Elbashir, J. Harborth, W. Lendeckel, A. Yalcin, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 411:494–498 (2001). doi:10.1038/35078107.

S. M. Elbashir, W. Lendeckel, and T. Tuschl. RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes & Development. 15:188–200 (2001). doi:10.1101/gad.862301.

M. A. Matzke, and J. A. Birchler. RNAi-mediated pathways in the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6:24–35 (2005). doi:10.1038/nrg1500.

J. Heyes, L. Palmer, K. Bremner, and I. MacLachlan. Cationic lipid saturation influences intracellular delivery of encapsulated nucleic acids. J. Controlled Release. 107:276–287 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.06.014.

G. Ronsin, C. Perrin, P. Guedat, A. Kremer, P. Camilleri, and A. J. Kirby. Novel spermine-based cationic gemini surfactants for gene delivery. Chem. Commun. 21:2234–2235 (2001). doi:10.1039/b105936j.

L. T. Weinstock, W. J. Rost, and C. C. Cheng. Synthesis of new polyamine derivatives for cancer chemotherapeutic studies. J. Pharm. Sci. 70:956–959 (1981). doi:10.1002/jps.2600700835.

Y. Chu, M. Masoud, and G. Gebeyehu. Synthesis and activity of transfection reagents for transport of biologically active agents or substances into cells PCT Int. Appl. WO1999US26825 19991112 [WO0027795], 130 pp. (2000).

R. M. Tyrrell, and M. Pidoux. Quantitative differences in host-cell reactivation of ultraviolet-damaged virus in human-skin fibroblasts and epidermal-keratinocytes cultured from the same foreskin biopsy. Cancer Res. 46:2665–2669 (1986).

J. L. Zhong, A. Yiakouvaki, P. Holley, R. M. Tyrrell, and C. Pourzand. Susceptibility of skin cells to UVA-induced necrotic cell death reflects the intracellular level of labile iron. J. Invest. Dermatol. 123:771–780 (2004). doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23419.x.

M. Gossen, and H. Bujard. Tight control of gene-expression in mammalian-cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:5547–5551 (1992). doi:10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547.

E. Kvam, V. Hejmadi, S. Ryter, C. Pourzand, and R. M. Tyrrell. Heme oxygenase activity causes transient hypersensitivity to oxidative ultraviolet A radiation that depends on release of iron from heme. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 28:1191–1196 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00205-7.

T. Mosmann. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 65:55–63 (1983). doi:10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4.

D. Fischer, T. Bieber, Y. X. Li, H. P. Elsasser, and T. Kissel. A novel non-viral vector for DNA delivery based on low molecular weight, branched polyethylenimine: Effect of molecular weight on transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity. Pharm. Res. 16:1273–1279 (1999). doi:10.1023/A:1014861900478.

A. L. C. Cardoso, S. Simoes, L. P. de Almeida, J. Pelisek, C. Culmsee, E. Wagner, and M. C. P. de Lima. siRNA delivery by a transferrin-associated lipid-based vector: a non-viral strategy to mediate gene silencing. J. Gene Med. 9:170–183 (2007). doi:10.1002/jgm.1006.

A. J. Geall, and I. S. Blagbrough. Rapid and sensitive ethidium bromide fluorescence quenching assay of polyamine conjugate–DNA interactions for the analysis of lipoplex formation in gene therapy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 22:849–859 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(00)00250-8.

P. L. Felgner, Y. Barenholz, J. P. Behr, S. H. Cheng, P. Cullis, L. Huang, J. A. Jessee, L. Seymour, F. Szoka, A. R. Thierry, E. Wagner, and G. Wu. Nomenclature for synthetic gene delivery systems. Hum. Gene Ther. 8:511–512 (1997). doi:10.1089/hum.1997.8.5-511.

R. M. Schiffelers, A. Ansari, J. Xu, Q. Zhou, Q. Q. Tang, G. Storm, G. Molema, P. Y. Lu, P. V. Scaria, and M. C. Woodle. Cancer siRNA therapy by tumor selective delivery with ligand-targeted sterically stabilized nanoparticle. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:e149 (2004). doi:10.1093/nar/gnh140.

T. Tagami, J. M. Barichello, H. Kikuchi, T. Ishida, and H. Kiwada. The gene-silencing effect of siRNA in cationic lipoplexes is enhanced by incorporating pDNA in the complex. Int. J. Pharm. 333:62–69 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.09.057.

C. F. Hung, T. L. Hwang, C. C. Chang, and J. Y. Fang. Physicochemical characterization and gene transfection efficiency of lipid, emulsions with various co-emulsifiers. Int. J. Pharm. 289:197–208 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.11.008.

D. G. Anderson, A. Akinc, N. Hossain, and R. Langer. Structure/property studies of polymeric gene delivery using a library of poly(beta-amino esters). Mol. Ther. 11:426–434 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.015.

X. Gao, and L. Huang. Potentiation of cationic liposome-mediated gene delivery by polycations. Biochemistry. 35:1027–1036 (1996). doi:10.1021/bi952436a.

S. C. De Smedt, J. Demeester, and W. E. Hennink. Cationic polymer based gene delivery systems. Pharm. Res. 17:113–126 (2000). doi:10.1023/A:1007548826495.

J. Panyam, and V. Labhasetwar. Biodegradable nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to cells and tissue. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 55:329–347 (2003). doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00228-4.

H. M. Ghonaim, S. Li, and I. S. Blagbrough. Very long chain N 4,N 9-diacyl spermines: non-viral lipopolyamine vectors for efficient plasmid DNA and siRNA delivery. Pharm. Res. 25: in press (2008).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support of the Egyptian Government to H.M.G. (a fully funded studentship) and to M.K.S. (a studentship under the Channel Scheme). We are grateful to Prof R.M. Tyrrell for the FEK4 and HtTA cell lines, to Dr C. Pourzand for helpful discussions, and we acknowledge S. Li (all University of Bath) for the synthesis of the N 4,N 9-dimyristoleoyl analogue. We thank NanoSight Ltd (Salisbury, UK) for the NanoSight LM10 and Beckman Coulter (High Wycombe, UK) for the Delsa™Nano.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soltan, M.K., Ghonaim, H.M., El Sadek, M. et al. Design and Synthesis of N 4,N 9-Disubstituted Spermines for Non-viral siRNA Delivery – Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of siFection Efficiency Versus Toxicity. Pharm Res 26, 286–295 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-008-9731-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-008-9731-z