Abstract

Purpose

Gliomas are the most commonly occurring brain tumour in adults and there remains no cure for these tumours with treatment strategies being based on tumour grade. All treatment options aim to prolong survival, maintain quality of life and slow the inevitable progression from low-grade to high-grade. Despite imaging advancements, the only reliable method to grade a glioma is to perform a biopsy, and even this is fraught with errors associated with under grading. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with amino acid tracers such as [18F]fluorodopa (18F-FDOPA), [11C]methionine (11C-MET), [18F]fluoroethyltyrosine (18F-FET), and 18F-FDOPA are being increasingly used in the diagnosis and management of gliomas.

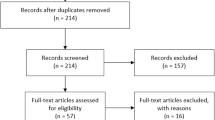

Methods

In this review we discuss the literature available on the ability of 18F-FDOPA-PET to distinguish low- from high-grade in newly diagnosed gliomas.

Results

In 2016 the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) and European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) published recommendations on the clinical use of PET imaging in gliomas. However, since these recommendations there have been a number of studies performed looking at whether 18F-FDOPA-PET can identify areas of high-grade transformation before the typical radiological features of transformation such as contrast enhancement are visible on standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Conclusion

Larger studies are needed to validate 18F-FDOPA-PET as a non-invasive marker of glioma grade and prediction of tumour molecular characteristics which could guide decisions surrounding surgical resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glioma is the most common primary brain tumour occurring in adults for which there is no cure. Gliomas are traditionally dichotomised by their grade into low-grade gliomas (LGG) which include grade I and II and high-grade gliomas (HGG) which includes grade III and IV tumours. The most recent publication of the fifth edition of the WHO classification of brain tumours incorporates new information on histological and molecular features into a layered integrated diagnosis and also introduces grading on a ‘within tumour type’ method [1].

The majority of patients with a low-grade glioma will present acutely with a seizure and as a result have a plain or contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) brain scan which identifies an area of abnormality that then requires further delineation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The minimum MRI sequences performed as part of the diagnostic workup for a suspected brain tumour include T2 weighted, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), T1 pre- and post-contrast and diffusion weighted sequences (DWI). The characteristic appearances of low-grade gliomas on MRI sequences will grossly depend on the grade and histological type of glioma. A provisional diagnosis can be made on imaging alone i.e. distinguishing between glioma versus metastasis, and within gliomas in distinguishing low-grade versus high-grade depending on a number of tumour characteristics [2]. However, there is diagnostic uncertainty about the prediction of WHO grade, and imaging alone is often inaccurate.

The distinction between low- and high-grade glioma on MRI is based on contrast enhancement from a disrupted blood brain barrier and to some extent from diffusion characteristics but this is not always truly predictive of grade and there is often diagnostic uncertainty. The confirmation of grade is normally made on biopsy sampling. However, sampling errors are not uncommon and up to one third of high-grade gliomas may not display the typical imaging characteristics of a high-grade glioma with enhancement [3]. Under grading is particularly associated with large heterogenous tumours and has been reported in 28% – 68% of cases [4,5,6]. With the introduction of molecular characterisation the risk of sample bias has reduced dramatically as the molecular markers are volume independent but not completely eliminated [7].

Additional imaging techniques and sequences are frequently used to provide additional information to help distinguish the type, grade of tumour and predict transformation. These include positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), MR perfusion and MR spectroscopy (MRS). Gliomas are notoriously heterogeneous in nature and as a result the use of MRS will demonstrate spectra that vary significantly depending on the region sampled [8]. The use of MR perfusion to detect grade has been demonstrated with varying results [9,10,11]. SPECT imaging has the disadvantage over PET of a lower resolution [12]. PET using amino acid tracers is becoming increasingly common to differentiate gliomas from metastases or other types of tumours [13]. The most commonly used amino acid PET tracers described are [11C]methionine (11C-MET), [18F]fluoroethyltyrosine (18F-FET) and [18F]fluorodopa (18F-FDOPA). 11C-MET has a short half-life of 20 min which limits its use to centres that have an onsite cyclotron. In comparison 18F-FET and 18F-FDOPA have much longer half-lives of 110 min making these tracers more available for clinical use. 18F-FDOPA demonstrates greater contrast for lesions outside of the striatum when compared to18F-FET [14]. A type of novel MRI technique, called oxygen enhanced MRI (OEMRI), has the ability to detect areas of hypoxia within solid tumours which if used within glioma could potentially detect areas of high-grade tumour and therefore affect prognosis if detected earlier [15].

The distinction between high-grade and low-grade glioma is important as both entities confer very different prognoses and management strategies. All treatment options aim to prolong survival, maintain quality of life and slow the inevitable progression from low- to high-grade. For both low- and high-grade gliomas the NICE guidelines recommend consideration of maximum safe gross total resection to confirm the histological and molecular diagnosis and for tumours that are not surgically resectable to perform a biopsy [16]. Following surgery, the standard treatment regime for grade IV gliomas (glioblastoma) is radiotherapy with concomitant temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide. In patients over the age of 70 treatment for grade IV gliomas is hypofractionated chemoradiotherapy [16]. Even with full treatment the median survival for grade IV glioblastomas is 12–24 months [17]. For grade II gliomas following surgery, oncological therapy is dependent on the patient’s age, extent of resection, 1p/19q codeletion presence and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status and consists of a combination of radiotherapy and PCV (procarbazine, CCNU [lomustine] and vincristine) chemotherapy [16] (Fig. 1). For grade III gliomas with a 1p/19q codeletion (anaplastic oligodendroglioma) treatment is similar with radiotherapy and PCV chemotherapy. Grade III tumours without a 1p/19q codeletion (anaplastic astrocytoma) require radiotherapy followed by adjuvant temozolomide. The use of non-invasive imaging parameters to accurately detect glioma grade could aid preoperative clinical decision-making when considering biopsy versus resection, extent of resection and timing of surgery.

Current recommendations

In 2016, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), European Association of Neurooncology (EANO) and the Response Assessment in Neurooncology (RANO) working group jointly published guidelines on the role of amino acid PET for imaging in gliomas [18, 19]. These evidence-based guidelines recommended a clinical role for the tracer 18F-FDOPA in the differentiation of glioma recurrence from treatment-induced changes, assessment of treatment response and assessment of prognosis. The recommendations reviewed the literature on the amino acid tracers 11C-MET, 18F-FET and 18F-FDOPA in glioma. Multiple studies have found that response to treatment is indicated on PET imaging by a decrease in amino acid tracer uptake with or without a reduction in the volume of metabolically active tumour [20,21,22] and 18F-FDOPA has been shown to demonstrate response to bevacizumab therapy better than conventional MRI [23, 24]. Treatment of gliomas with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy can result in treatment-related changes. There is a temporary alteration in the blood brain barrier (BBB) resulting in contrast enhancement on MRI imaging which mimics tumour progression and is called pseudoprogression. Pseudoprogression typically occurs within 12 weeks of completion of treatment [25, 26]. Differentiating pseudoprogression and radionecrosis from true tumour progression can be challenging with conventional MRI alone and often additional imaging techniques such as amino acid PET or MR spectroscopy are employed [27]. In a prospective study of 35 patients with proven glioma, Karunanithi et al. found the sensitivity of 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT in determining recurrence in glioma to be 100% when compared to 92% with contrast-enhanced MRI and a specificity of 89% with 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT versus 44% for contrast enhanced-MRI [28]. Karunanithi et al. in a separate study of 28 patients with proven glioma compared 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT with 18F-Fluoro-deoxy-glucose (FDG)-PET/CT and found the sensitivity and specificity for FDG was inferior at 48% and 100% respectively and in comparison, 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT was 100% and 86% respectively [29]. A meta-analysis by de Zwart et al. found 18F-FDOPA to be superior over 11C-MET and 18F-FET in differentiating tumour progression from treatment-related changes with a pooled sensitivity of 85–100% and specificity of 72–100% when compared to 11C-MET (sensitivity 80–98%, specificity 61–91%) and 18F-FET (sensitivity 81–95%, specificity 71–93%) [30]. A study by Villani et al. with 50 patients found a potential role of FDOPA in prognostication of low-grade gliomas [31]. The authors found that disease duration and a maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) of > 1.75 was predictive of progression and superior to MRI in detection of progression and therefore prognosis, as transformation to high-grade is the key determinant in patient survival. When the recommendations were published there were conflicting results on the ability of 18F-FDOPA-PET to predict glioma grade and 18F-FDOPA was not recommended for this use. This article will review previously published results and results from recent studies that have become available since the publication of these guidelines.

18F-FDOPA PET

[18F]fluorodopa, 3, 4-dihydroxy-6-[18F]fluoro-L-phenylalanine, (18F-FDOPA) was originally developed for brain imaging in patients with movement disorders. It consists of an amino acid, phenylalanine, attached to a radioisotope, fluorine (Fig. 2a), that is able to cross the blood brain barrier and act as a precursor for dopamine. Phenylalanine is an essential aromatic amino acid with a neutral charge. Gliomas require a continuous supply of amino acids to maintain protein synthesis and cell proliferation. These amino acids reach the tumour cells via amino acid transporters. Amino acids are cationic, anionic or neutral, and their transport across a membrane is regulated by amino acid transporters [32]. Amino acid transporters can be uniporter, antiporter or symporter, each transporting certain amino acids (Fig. 2b). One of these neutral transporter systems is the L-type amino acid transporter (LAT) which is a membrane bound Na+ independent transport protein regulating the transport of essential amino acids across cell membranes. There are four main types of LAT transporter; LAT1 (SLC7A5), LAT2 (SLC7A8), LAT3 (SLC43A1) and LAT4 (SLC43A2). LAT1 is a polypeptide consisting of 507 amino acids and 12 transmembrane regions with a molecular weight of 55 kDa [33]. LAT1 forms a heterodimeric complex with CD98 via a disulphide bond. CD98 is a polypeptide of 630 amino acids and a molecular weight of 68 kDa. CD98 is thought to be crucial for LAT1 to function but it has been demonstrated that LAT1 is the only transport component of the LAT1/CD98 heterodimer [33, 34]. Substrates that bind the LAT1 transporter must have a histidine group, a carboxylic group and an amino group [35]. LAT1 controls the movement of neutral essential amino acids which include histidine, leucine, isoleucine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan and valine, into cells in exchange for the efflux of intracellular substrates such as glutamine, histidine and tyrosine (Fig. 3) [36, 37]. LAT1 mRNA is expressed most strongly in the brain, placenta, colon, testis and spleen and is expressed at low levels in the lungs, liver and heart [38]. Studies have demonstrated that LAT1 expression is higher than in normal tissues in cancers [39]. Tumour progression in gliomas requires a constant supply of amino acids for protein synthesis and cell proliferation. LAT1 expression correlates with proliferation of cancer cells enabling rapid growth as it plays role in cell growth, transcription and translation through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling pathway which facilitates protein synthesis [35, 40].

When administered intravenously, 1% of the 18F-FDOPA will cross the blood brain barrier via the LAT1 transporter and the rest remains in the periphery where it is converted to 3-O-methyl-6-fluoro-L-DOPA (OMFD) by catechol O-methyl transferase (COMT) or into [18F]fluorodopamine by aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD). Once across the BBB FDOPA is converted to [18F]fluorodopamine by aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) (Fig. 4). Fluorodopamine behaves like dopamine in vivo and is either stored in pre-synaptic vesicles in the striatum or metabolised into [18F]6-fluoro-L-3,4-dihydrophenylacetic acid (FDOPAC) by monoamine oxidase (MAO) and then into [18F]6-fluorohomovanillic acid (FHVA) by COMT [41]. The 18F-FDOPA metabolites are renally excreted. In glioma cells the 18F-FDOPA is not metabolised [42]. To reduce the systemic metabolism of 18F-FDOPA and increase bioavailability and cerebral uptake, the decarboxylase inhibitor carbidopa is often administered prior to administration of 18F-FDOPA. Bros et al. found that in imaging of gliomas with 18F-FDOPA-PET, premedication with carbidopa resulted in a 50% increase in uptake in all brain structures but when corrected for the tumour-to-healthy-brain ratio did not impact image interpretation [43].

18F-FDOPA has been demonstrated to be advantageous over other amino acid PET tracers as it is predominantly transported by the L-type amino acid transporter without significant uptake into surrounding normal brain parenchyma with the exception of the basal ganglia, thereby allowing easier discrimination of uptake within the tumour [44, 45]. Despite this limitation, in gliomas involving the basal ganglia 18F-FDOPA has been shown be able to accurately delineate tumour boundaries [46, 47]. 18F-FDOPA is more readily available in clinical practice compared to 11C-MET which requires an on-site cyclotron due to its short half-life of 20 minutes whereas the half-life of 18F-FDOPA is 110 minutes [48]. 18FDG has been extensively used for imaging in brain tumours with a meta-analysis of 26 studies that reported a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 78% in detecting gliomas irrespective of grade [49,50,51]. However, 18FDG measures glucose metabolism and therefore it tends to accumulate in the grey matter which can interfere with the ability to differentiate tumour grade reliably. Tumours with low glucose metabolism, such as low-grade gliomas, are often not well visualised with FDG [52]. 18F-FDOPA has been shown to have a higher uptake in low-grade gliomas than FDG [53]. 18F-FDOPA uptake into glioma cells is thought to be higher in areas with high-grade features due to an increase in the transport of amino acids into tumour cells which is led by an increase in expression of the L-type amino acid transport system and subsequently has the potential to be able to detect areas of high-grade transformation within low-grade glioma before the typical radiological features of transformation such as contrast enhancement are visible on conventional MRI [54, 55]. Ledezma et al. found in a small number of cases that 18F-FDOPA tracer activity was able to identify tumour not visible on conventional MRI [52].

Role of 18F-FDOPA in differentiating high- and low-grade gliomas

The standardised uptake value (SUV) is a measure of 18F-FDOPA uptake and is a calculation of the ratio of tissue radioactivity concentration (in kBq/ml) at a given time divided by the administered activity at the time of injection (in MBq) divided by the body weight (in kg) [56]. Despite studies investigating 18F-FDOPA SUV in differing grades of glioma there are currently no agreed thresholds for SUV in routine clinical practice with 18F-FDOPA for distinguishing between high and low-grade gliomas. The Joint EANM/EANO/RANO guidelines do however provide thresholds for 18F-FDOPA in delineating tumour extent, detecting tumour recurrence and identification of response to treatment with bevacizumab [18]. For extent of tumour Pafundi et al. identified that a tumour-to-normal-brain ratio (TBR) of greater than 2.0 corresponded to high-grade disease [57]. For detection of tumour recurrence, a tumour to striatum ratio (TSR) max of 2.1 and a TSRmean of 1.8 are described [58]. Scwharzenberg et al. were able to show that by using 18F-FDOPA-PET at two weeks following initiation of bevacizumab therapy for recurrent high-grade gliomas the threshold for a positive response to treatment was found to be a brain tumour volume decrease of greater than 35% or a metabolically active tumour volume of less than 18 mL at two weeks [24].

Literature published prior to joint EANM/EANO/RANO guidelines

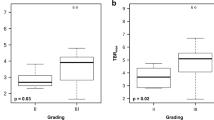

Prior to the publication of the 2016 recommendations there were two main studies that have addressed 18F-FDOPA PET in predicting glioma grade. The first was by Pafundi et al. who performed a prospective pilot study with 10 patients [57]. Of these, 8 were newly diagnosed and 2 were recurrent gliomas. For the patients undergoing surgical resection, a maximum of three stereotactic biopsy targets were planned using various PET SUVs along a single trajectory with the PET/CT and contrast enhanced MRI fused using MIM Maestro software. 23 biopsy samples were obtained using neuronavigation on the preplanned targets and each tissue sample was analysed and graded along with recording the average cellularity and average Ki-67 index. PET/CT was performed 10 min after the tracer injection and carbidopa premedication was not used. A strong association was found of 18F-FDOPA SUVmax with tumour grade. The authors identified that there were significant differences between distinguishing grade II and IV (p = 0.008) and grade III and IV (p = 0.024) when using static 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT in 8 patients. No significant difference was found between the SUVmax in grade II and grade III tumours (p = 0.17). This may have been because there were only two grade II astrocytomas in the cohort. By removing the oligodendroglioma samples the authors found a significant correlation between 18F-FDOPA SUVmean and histological cellularity (p = 0.01). Higher cellularity indicates histologically higher-grade features. A TBR of > 2.0 was able to define high-grade components of astrocytic tumours. The oligodendroglioma biopsy samples, of which there were three, were removed from the final analysis as the study found that the 18F-FDOPA SUVmax was much greater in comparison to the grade II astrocytomas and this has been previously described with the tracers 11C-MET55 and 18F-FET [60].

The second study by Fueger et al. included 59 patients of which 22 where newly diagnosed and 37 recurrent gliomas of varying grades (grade II n = 22, grade III n = 19, grade IV n = 27) that underwent static 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT before surgery [61]. The PET/CT was performed 10 min after the tracer injection and carbidopa premedication was not administered. Each tumour was graded histologically and Ki-67 expression measured. The authors found a significant difference in SUVmax in newly diagnosed gliomas between grade II and III (p = 0.044), between grade II and IV (p = 0.007) and between grade III and IV tumours (p = 0.010) and concluded that a 18F-FDOPA SUVmax of 2.72 was the cut-off to distinguish low- and high-grade newly diagnosed gliomas. There was no significant difference between grades in the recurrent tumours. The lack of correlation in tumour recurrence could be explained by damage to the BBB from radiation therapy leading to increased vascular permeability resulting in an increase in non-carrier (LAT1) mediated transport of 18F-FDOPA from endothelial cells into tumour cells [62]. The histopathological samples from this study were much larger compared to Pafundi et al. [57] and therefore would have not considered 18F-FDOPA uptake heterogeneity within the tumour.

Literature published after Joint EANM/EANO/RANO guidelines available

The following section will describe the new data published following the 2016 recommendations and the impact of this data. Todeschi et al. recently performed a single centre prospective study on 16 newly diagnosed gliomas and 4 recurrent gliomas using static 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT [63]. The PET/CT was performed 30 min after tracer injection and no carbidopa premedication was administered. Biopsy targets were based on regions of tracer hypermetabolism and hypometabolism. In this series the authors found that a SUVmax threshold of > 1.75 demonstrated a greater yield in terms of diagnosis of high-grade gliomas. The authors concluded that the use of 18F-FDOPA-PET allowed for better targeting of metabolically active areas of tumour to reduce biopsy sampling bias but when used alone was unable to reliably distinguish tumour grade (SUVmax low-grade 2.03 and 2.18 for high-grade, p = 0.64). The biopsies were taken using a robotic arm with a biopsy needle as opposed to a craniotomy for tumour resection as in the Pafundi study [57]. The result is that the preplanned targets and resultant biopsies are likely to have been more accurate as they would have not been affected by brain shift from opening the dura and CSF drainage as would have been the case with the Pafundi study [57]. However, the single trajectory resulted in two biopsy targets (an area of hypometabolism and hypermetabolism) that were in close proximity with little margin for error in coregistration of the patient with the imaging.

The majority of 18F-FDOPA-PET studies have used static parameters for 18F-FDOPA uptake. Static PET provides a single snapshot of the tracer uptake whereas dynamic PET takes multiple snapshots at different timepoints. The advantage of dynamic PET when used alongside kinetic modelling allows creation of time-activity curves (TAC) which can provide additional information on the pharmacokinetics of 18F-FDOPA in brain tumours. The assumption is that high-grade gliomas will quickly take up 18F-FDOPA (the wash-in) when injected in comparison to low-grade gliomas which will have a slow wash-in period [64]. Previously Schiepers et al. have directly compared static and dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET in brain tumours [42]. In this study 37 patients were included of which 33 were primary brain tumours. A significant difference was found between tracer volume distribution between newly diagnosed low-grade and high-grade tumours (p ≤ 0.01) and between newly diagnosed high-grade tumours and tumours with post-treatment changes. Nioche et al. similarly performed static and dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT for 33 patients published in 2013 and found a SUVmean threshold of 2.5 in determining the grade with a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 66% [65]. There was no significant improvement in these results when comparing static and dynamic imaging. Dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET appears to be more useful in newly diagnosed gliomas and less useful for detection of recurrence or progression as evidence by Zaragori et al. [66]. This study identified 51 patients with suspected glioma recurrence or progression who underwent 18F-FDOPA-PET and found that no additional significant information was gained from performing dynamic imaging. Xiao et al. in a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled sensitivity of 0.71 and specificity of 0.86 for grading newly diagnosed gliomas with static FDOPA PET [67].

Despite the sensitivity and specificity of static 18F-FDOPA-PET, dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET has the advantage of being able to detect a tumour’s molecular characteristics as demonstrated by Ginet et al. [68]. This retrospective study looked at 58 patients with newly diagnosed glioma who underwent either biopsy (n = 24) or surgical resection (n = 34) and preoperative static and dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET. Patients were given carbidopa one hour prior to PET imaging. They found that only the dynamic parameters of time-to-peak (TTP) which represents the time from tracer injection to maximum SUV, area under the curve (AUC) and curve slopes were significant in predicting the IDH-mutation status (TTP p ≤ 0.001, AUC p = 0.789, slope p = 0.013). For prediction of the 1p/19q co-deletion status the TTP was the only dynamic parameter found to be statistically significant (p = 0.034). The static imaging did not significantly correlate with the molecular subtypes. This could be because static imaging is just a snapshot in time whereas dynamic imaging captures the rate of 18F-FDOPA tracer uptake and washout so more information is available. Isal et al. retrospectively looked at 20 patients with histologically confirmed newly diagnosed grade II and grade III gliomas that had serial static 18F-FDOPA PET [69]. The authors found that a SUVmax of greater than 1.8 is predictive of the presence of an IDH-mutation. Similarly, Cicone et al. performed static 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT in 33 patients following surgery but before initiation of chemoradiotherapy [70]. The SUVmax, TBR and TSR were not statistically significant between tumours that were IDH-mutant or IDH-wildtype and that no difference was found between 1p/19q co-deleted and non-co-deleted patients. In addition, no statistically significant difference was seen between low- and high-grade gliomas (p ≥ 0.2).

The presence of MGMT methylation indicates silencing of the MGMT gene resulting in a reduction in the capability of tumour cells to repair damage from alkylating agents such as temozolomide and confers a better prognosis [71]. Cimini et al. performed static 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT in 72 patients post-surgery and found no difference between the presence of MGMT methylation versus unmethylation (p = 0.15) and no difference between IDH-mutant and IDH-wildtype gliomas (p = 0.79) [72]. One explanation for the results in both these studies may be that the 18F-FDOPA-PET scans were performed following surgical biopsy and it has already been shown that inflammation and macrophage response seen post-surgery can alter 18F-FDOPA uptake [73, 74]. The ability to detect IDH-mutation status on imaging is novel and could potentially play a role in management discussions with patient’s at diagnosis as IDH-wildtype tumours regardless of grade have a shorter median overall survival, < 2 years, when compared to IDH-mutant gliomas [75].

The GLIROPA clinical trial form Girard et al. included only newly diagnosed diffuse gliomas of which 32 biopsies were acquired from 14 patients [56]. Preoperative static and dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET was performed followed by stereotactically guided biopsies (up to three per patient). The PET/CT was performed 10 min after tracer injection and no carbidopa premedication was administered. Each biopsy sample was graded independently but there was a much higher number of high-grade tumour samples (n = 23) in comparison to low-grade tumour samples (n = 9). The authors established that the static PET parameters were not significantly different between grades but the kinetic analysis from dynamic image acquisition was more accurate for glioma grading. However, the time between the 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT and stereotactic biopsy to confirm the histopathological grade was as long as 110 days during which time the tumour had the potential to transform to a higher grade. Janvier et al. performed a retrospective review published in 2015 on 31 patients of which 6 were recurrent gliomas and 25 newly diagnosed who had undergone static 18F-FDOPA-PET [76]. The study found that the SUVmean and tumour-to-normal-tissue ratio (T/N) best correlated to the grade (p = < 0.05) with a cut-off for SUVmean of 1.33. Bund et al. found that in a subset of low-grade gliomas, in discriminating between dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour and grade II oligodendroglioma SUVmax was significant (p ≤ 0.01) and also between low-and high-grade gliomas a SUVmax cut off of 2.16 was found [77]. A prospective study in 45 patients with suspected glioma who underwent preintervention static 18F-FDOPA-PET and found that a T/N SUVmax ratio greater 1.7 was able to differentiate high-grade glioma from other graded lesions [78].

In a pilot study Ponisio et al. used dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET/MRI with stereotactically linked histopathology data in 10 patients of which 4 were recurrent tumours, obtaining a total of 23 biopsies. The authors identified that the results of the 18F-FDOPA-PET/MRI had a positive impact on patient management in 4 cases including performing additional biopsies and altering surgical strategies in terms of extent of resection. In addition, the authors found a strong correlation between tumour SUV parameters and the Ki-67 index reflecting cell proliferation. Despite the promising results and impact on management Ponisio et al. concluded that dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET/MRI was independent of WHO grade and did not significantly differentiate between low- and high-grade gliomas. This pilot study and Todeschi et al. [63] differs from the other studies with stereotactically linked histopathological data [56, 57] in that the 18F-FDOPA-PET was combined with MRI rather than CT. There are implications in terms of cost, reduction in radiation exposure and accessibility in using PET/MRI but they are reported to perform equally [79].

There has been a lot of work on the ability of 18F-FDOPA-PET to differentiate between low- and high-grade gliomas since the 2016 recommendations were published which have been discussed but there are a number of limitations to consider. Firstly, many studies include both newly diagnosed and recurrent gliomas together. Macrophages have been reported to have high levels of amino acid transport and therefore 18F-FDOPA uptake. As a result, 18F-FDOPA uptake levels may be falsely positive following surgery and radiotherapy due to the presence of macrophages around the resection cavity and in irradiated tumours [73, 74]. For this reason, ideally newly diagnosed and recurrent gliomas should be reviewed separately to exclude treatment bias and if not possible, the time delay between surgery and 18F-FDOPA imaging should be considered and any uptake around a resection cavity should be interpreted with care. Secondly, in the majority of studies the number of participants is generally low and there are differing protocols from the biopsy and surgical technique to the co-registration of PET/CT with MRI and histological interpretation of tissue samples and therefore it is impossible to completely merge data from different studies. In addition, there are few studies [56, 57, 63, 80] that have integrated biopsy location with histopathological data and 18F-FDOPA uptake. This is important as 18F-FDOPA uptake can vary widely within a tumour. The 18F-FDOPA uptake heterogeneity may represent heterogeneity in terms of the histopathological features and therefore grade, which can alter management strategies and ultimately prognosis. Finally, the current published studies are all single centre and there is a requirement here for multicentre studies to be completed.

Future work

Additional larger prospective studies are needed with biopsy validated dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT and PET/MRI in treatment naïve gliomas to confirm the promising correlation seen in the literature. A stage 2 clinical trial run by the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, United States) has now closed to enrolment having recruited 72 patients. With the aim of determining 18F-FDOPA-PET thresholds for distinguishing low- from high-grade glioma [81]. The FIG (18F-FDOPA-PET PET imaging in glioma) study is currently recruiting patients in Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Oxford, UK) with the aim of opening to recruitment at two further sites later this year. The FIG study is a feasibility study investigating 18F-FDOPA-PET and oxygen-enhanced MR guided histopathology in patients with suspected low-grade gliomas in a multi-centre setting [82]. The study will include up to 168 biopsies in 21 participants recruited from multiple neurosurgical centres in the UK. This study will be one of the first and largest study to use dynamic FDOPA PET/CT in determining grade of gliomas in a multi-centre setting.

The recent publication of the 2021 WHO classification of central nervous system tumours has incorporated numerous molecular changes that support the integrated diagnosis for each tumour type1 (Table 1). These additional molecular changes open up an opportunity for evaluation of dynamic 18F-FDOPA-PET in detection of molecular markers similar to the previous studies into IDH-mutation status, 1p/19q co-deletion status and presence of MGMT methylation [68,69,70,71,72] (See Table 2).

Conclusions

The literature demonstrates the capability of 18F-FDOPA-PET to differentiate low- from high-grade gliomas as well as the presence of an IDH-mutation, the 1p/19q co-deletion status and the MGMT methylation status. The FIG multicentre study will possibly answer questions on the introduction of preoperative 18F-FDOPA-PET into the routine imaging work up for glioma patients to guide surgical management. Detecting areas of high-grade transformation more effectively would allow for earlier clinical intervention, optimisation of surgical planning and resection strategies with the potential to lengthen progression free survival and therefore ultimately prognosis.

References

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P et al (2021) The WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23(8):1231–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noab106

Smits M (2016) Imaging of oligodendroglioma. Br J Radiol 89(1060):20150857. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20150857

Henson JW, Gaviani P, Gonzalez RG (2005) MRI in treatment of adult gliomas. Lancet Oncol 6(3):167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(05)01767-5

Muragaki Y, Chernov M, Maruyama T et al (2008) Low-grade glioma on stereotactic biopsy: how often is the diagnosis accurate? Minim Invasive Neurosurg 51(5):275–279. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1082322

Jackson RJ, Fuller GN, Abi-Said D et al (2001) Limitations of stereotactic biopsy in the initial management of gliomas. Neuro-Oncology 3(3):193-200

Beiko J, Suki D, Hess KR et al (2014) IDH1 mutant malignant astrocytomas are more amenable to surgical resection and have a survival benefit associated with maximal surgical resection. Neuro Oncol 16(1):81–91

Kim BYS, Jiang W, Beiko J et al (2014) Diagnostic discrepancies in malignant astrocytoma due to limited small pathological tumor sample can be overcome by IDH1 testing. J Neurooncol 118:405–412

Padelli F, Mazzi F, Erbetta A, et al (2022) In vivo brain MR spectroscopy in gliomas: clinical and pre‑clinical chances. Clinical and Translational Imaging 10:495–515

Hilario A, Ramos A, Perez-Nuñez A et al (2012) The added value of apparent diffusion coefficient to cerebral blood volume in the preoperative grading of diffuse gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 33(4):701–707. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A2846

Law M, Yang S, Wang H et al (2003) Glioma grading: sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of perfusion MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopic imaging compared with conventional MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 24(10):1989–1998

Toyooka M, Kimura H, Uematsu H, Kawamura Y, Takeuchi H, Itoh H (2008) Tissue characterization of glioma by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: glioma grading and histological correlation. Clin Imaging 32(4):251–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2007.12.006

Palumbo B, Buresta T, Nuvoli S et al (2014) SPECT and PET serve as molecular imaging techniques and in vivo biomarkers for brain metastases. Int J Mol Sci 15(6):9878–9893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15069878

Chen W (2007) Clinical applications of PET in brain tumors. J Nucl Med 48(9):1468–1481. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.106.037689

Galldiks N, Lohmann P, Cicone F, Langen K (2019) FET and FDOPA PET Imaging in Glioma. In: Pope W (ed) Glioma Imaging. Springer International Publishing, pp211–221

O’Connor JPB, Robinson SP, Waterton JC (2019) Imaging tumour hypoxia with oxygen-enhanced MRI and BOLD MRI. BJR. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20180642

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Brain tumours (primary) and brain metastases in over 16s [NICE Guideline No.99]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng99

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352(10):987–996. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043330

Law I, Albert NL, Arbizu J et al (2019) Joint EANM/EANO/RANO practice guidelines/SNMMI procedure standards for imaging of gliomas using PET with radiolabelled amino acids and [18F]FDG: version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46(3):540–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-018-4207-9

Albert NL, Weller M, Suchorska B et al (2016) Response assessment in neuro-oncology working group and european association for neuro-oncology recommendations for the clinical use of PET imaging in gliomas. Neuro Oncol 18(9):1199–1208. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/now058

Galldiks N, Langen KJ, Holy R et al (2012) Assessment of treatment response in patients with glioblastoma using O-(2–18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET in comparison to MRI. J Nucl Med 53(7):1048–1057. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.111.098590

Galldiks N, Kracht LW, Burghaus L et al (2006) Use of 11C-methionine PET to monitor the effects of temozolomide chemotherapy in malignant gliomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 33(5):516–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-005-0002-5

Jansen NL, Suchorska B, Schwarz SB et al (2013) [18F]fluoroethyltyrosine-positron emission tomography-based therapy monitoring after stereotactic iodine-125 brachytherapy in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Mol Imaging 12(3):137–147

Harris RJ, Cloughesy TF, Pope WB et al (2012) 18F-FDOPA and 18F-FLT positron emission tomography parametric response maps predict response in recurrent malignant gliomas treated with bevacizumab. Neuro Oncol 14(8):1079–1089. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nos141

Schwarzenberg J, Czernin J, Cloughesy TF et al (2014) Treatment response evaluation using 18F-FDOPA PET in patients with recurrent malignant glioma on bevacizumab therapy. Clin Cancer Res 20(13):3550–3559. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1440

Langen KJ, Galldiks N, Hattingen E, Shah NJ (2017) Advances in neuro-oncology imaging. Nat Rev Neurol 13(5):279–289. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.44

Galldiks N, Lohmann P, Albert NL, Tonn JC, Langen KJ (2019) Current status of PET imaging in neuro-oncology. Neurooncol Adv. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdz010

Ellingson BM, Chung C, Pope WB, Boxerman JL, Kaufmann TJ (2017) Pseudoprogression, radionecrosis, inflammation or true tumor progression? challenges associated with glioblastoma response assessment in an evolving therapeutic landscape. J Neurooncol 134(3):495–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-017-2375-2

Karunanithi S, Sharma P, Kumar A et al (2013) Comparative diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced MRI and (18)F-FDOPA PET-CT in recurrent glioma. Eur Radiol 23(9):2628–2635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-013-2838-6

Karunanithi S, Sharma P, Kumar A et al (2013) 18F-FDOPA PET/CT for detection of recurrence in patients with glioma: prospective comparison with 18F-FDG PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 40(7):1025–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-013-2384-0

de Zwart PL, van Dijken BRJ, Holtman GA, Stormezand GN, Dierckx RAJO, Jan van Laar P et al (2020) Diagnostic accuracy of PET tracers for the differentiation of tumor progression from treatment-related changes in high-grade glioma: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Nucl Med 61(4):498–504

Villani V, Carapella CM, Chiaravalloti A et al (2015) The role of PET [18F]FDOPA in evaluating low-grade Glioma. Anticancer Res 35(9):5117–5122

Gauthier-Coles G, Vennitti J, Zhang Z et al (2021) Quantitative modelling of amino acid transport and homeostasis in mammalian cells. Nat Commun 12(1):5282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25563-x

Napolitano L, Scalise M, Galluccio M, Pochini L, Albanese LM, Indiveri C (2015) LAT1 is the transport competent unit of the LAT1/CD98 heterodimeric amino acid transporter. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 67:25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2015.08.004

Puris E, Gynther M, Auriola S, Huttunen KM (2020) L-Type amino acid transporter 1 as a target for drug delivery. Pharm Res 37(5):88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-020-02826-8

Scalise M, Galluccio M, Console L, Pochini L, Indiveri C (2018) The human SLC7A5 (LAT1): the intriguing histidine/large neutral amino acid transporter and its relevance to human health. Front Chem 6:243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2018.00243

Zaragozá R (2020) Transport of amino acids across the blood-brain barrier. Front Physiol 11:973. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00973

Herholz K (2017) Brain tumors: an update on clinical PET research in gliomas. Semin Nucl Med 47(1):5–17. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2016.09.004

Kanai Y, Segawa H, Miyamoto K-i, Uchino H, Takeda E, Endou H (1998) Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 Antigen (CD98)*. J Biol Chem 273(37):23629–23632

Zhang J, Xu Y, Li D et al (2020) Review of the correlation of LAT1 with diseases: mechanism and treatment. Front Chem 8:564809. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2020.564809

Wang Q, Holst J. 2015 L-type amino acid transport and cancer: targeting the mTORC1 pathway to inhibit neoplasia. American Journal of Cancer Research. 5(4):1281-94

Endres CJ, DeJesus OT, Uno H, Doudet DJ, Nickles JR, Holden JE (2004) Time profile of cerebral [18F]6-fluoro-L-DOPA metabolites in nonhuman primate: implications for the kinetics of therapeutic L-DOPA. Front Biosci 9:505–512. https://doi.org/10.2741/1224

Schiepers C, Chen W, Cloughesy T, Dahlbom M, Huang S-C (2007) 18F-FDOPA kinetics in brain tumors. J Nuclear Med. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.106.039321

Bros M, Zaragori T, Rech F et al (2021) Effects of carbidopa premedication on 18F-FDOPA PET imaging of glioma: a multiparametric Analysis. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13215340

Ono M, Oka S, Okudaira H et al (2013) Comparative evaluation of transport mechanisms of trans-1-amino-3-[(1)(8)F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid and L-[methyl-(1)(1)C]methionine in human glioma cell lines. Brain Res 1535:24–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2013.08.037

Oka S, Okudaira H, Ono M et al (2014) Differences in transport mechanisms of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid in inflammation, prostate cancer, and glioma cells: comparison with L-[methyl-11C]methionine and 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose. Mol Imaging Biol 16(3):322–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-013-0693-0

Becherer A, Karanikas G, Szabó M et al (2003) Brain tumour imaging with PET: a comparison between [18F]fluorodopa and [11C]methionine. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30(11):1561–1567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-003-1259-1

Morana G, Puntoni M, Garrè ML, Massollo M, Lopci E, Naseri M et al (2016) Ability of (18)F-DOPA PET/CT and fused (18)F-DOPA PET/MRI to assess striatal involvement in paediatric glioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 43(9):1664–1672

Lapa C, Linsenmann T, Monoranu CM, Samnick S, Buck AK, Bluemel C et al (2014) Comparison of the amino acid tracers 18F-FET and 18F-DOPA in high-grade glioma patients. J Nucl Med 55(10):1611–1616

Nihashi T, Dababreh I, Terasawa T (2013) Diagnostic accuracy of PET for recurrent glioma diagnsois: a meta-analysis. AJNR 34(5):941–1011

Nihashi T, Dahabreh IJ, Terasawa T (2013) Diagnostic accuracy of PET for recurrent glioma diagnosis: a meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 34(5):944–950. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A3324

O’Connor JP, Naish JH, Parker GJ et al (2009) Preliminary study of oxygen-enhanced longitudinal relaxation in MRI: a potential novel biomarker of oxygenation changes in solid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 75(4):1209–1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.040

Ledezma CJ, Chen W, Sai V et al (2009) 18F-FDOPA PET/MRI fusion in patients with primary/recurrent gliomas: initial experience. Eur J Radiol 71(2):242–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.04.018

Chen W, Silverman D, Delaloye S et al (2006) 18F-FDOPA PET imaging of brain tumors: comparison study with 18F-FDG PET and evaluation of diagnostic accuracy. J Nucl Med 47(6):904–911

Youland RS, Kitange GJ, Peterson TE et al (2013) The role of LAT1 in 18F-DOPA uptake in malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol 111:11–18

Nawashiro H, Otani N, Uozumi Y et al (2005) High expression of L-type amino acid transporter 1 in infiltrating glioma cells. Brain Tumor Pathol 22(2):89–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10014-005-0188-z

Girard A, Le Reste PJ, Metais A et al (2021) Additive value of dynamic FDOPA PET/CT for glioma grading. Front Med (Lausanne) 8:705996. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.705996

Pafundi DH, Laack NN, Youland RS et al (2013) Biopsy validation of 18F-DOPA PET and biodistribution in gliomas for neurosurgical planning and radiotherapy target delineation: results of a prospective pilot study. Neuro Oncol 15(8):1058–1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/not002

Herrmann K, Czernin J, Cloughesy T et al (2014) Comparison of visual and semiquantitative analysis of 18F-FDOPA-PET/CT for recurrence detection in glioblastoma patients. Neuro Oncol 16(4):603–609. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/not166

Hatakeyama T, Kawai N, Nishiyama Y et al (2008) 11C-methionine (MET) and 18F-fluorothymidine (FLT) PET in patients with newly diagnosed glioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 35(11):2009–2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-0847-5

Jansen NL, Schwartz C, Graute V et al (2012) Prediction of oligodendroglial histology and LOH 1p/19q using dynamic [(18)F]FET-PET imaging in intracranial WHO grade II and III gliomas. Neuro Oncol 14(12):1473–1480. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nos259

Fueger BJ, Czernin J, Cloughesy T et al (2010) Correlation of 6–18F-fluoro-L-dopa PET uptake with proliferation and tumor grade in newly diagnosed and recurrent gliomas. J Nucl Med 51(10):1532–1538. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.110.078592

Langen KJ, Mühlensiepen H, Holschbach M, Hautzel H, Jansen P, Coenen HH (2000) Transport mechanisms of 3-[123I]iodo-alpha-methyl-L-tyrosine in a human glioma cell line: comparison with [3H]methyl]-L-methionine. J Nucl Med 41(7):1250–1255

Todeschi J, Bund C, Cebula H et al (2019) Diagnostic value of fusion of metabolic and structural images for stereotactic biopsy of brain tumors without enhancement after contrast medium injection. Neurochirurgie 65(6):357–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2019.08.002

Verger A, Imbert L, Zaragori T (2021) Dynamic amino-acid PET in neuro-oncology: a prognostic tool becomes essential. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-021-05530-w

Nioche C, Soret M, Gontier E et al (2013) Evaluation of quantitative criteria for glioma grading with static and dynamic 18F-FDopa PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med 38(2):81–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0b013e318279fd5a

Zaragori T, Ginet M, Marie PY et al (2020) Use of static and dynamic [18F]-F-DOPA PET parameters for detecting patients with glioma recurrence or progression. EJNMMI Res 10(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-020-00645-x

Xiao J, Jin Y, Nie J, Chen F, Ma X (2019) Diagnostic and grading accuracy of 18FFDOPA PET and PET/CT in patients with gliomas: a systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Cancer 19(1):767

Ginet M, Zaragori T, Marie PY et al (2020) Integration of dynamic parameters in the analysis of 18F-FDopa PET imaging improves the prediction of molecular features of gliomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 47(6):1381–1390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-019-04509-y

Isal S, Gauchotte G, Rech F et al (2018) A high 18F-FDOPA uptake is associated with a slow growth rate in diffuse grade II-III gliomas. Br J Radiol 91(1084):20170803. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20170803

Cicone F, Carideo L, Scaringi C et al (2019) F-DOPA uptake does not correlate with IDH mutation status and 1p/19q co-deletion in glioma. Ann Nucl Med 33(4):295–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12149-018-01328-3

Rao AM, Quddusi A, Shamim MS (2018) The significance of MGMT methylation in glioblastoma multiforme prognosis. J Pak Med Assoc 68(7):1137–1139

Cimini A, Chiaravalloti A, Ricci M, Villani V, Vanni G, Schillaci O (2020) MGMT promoter methylation and IDH1 mutations do not affect [18F]FDOPA uptake in primary brain tumors. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207598

Somme F, Bender L, Namer IJ, Noël G, Bund C (2020) Usefulness of 18F-FDOPA PET for the management of primary brain tumors: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Imaging 20(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-020-00348-5

Tabatabaei P, Visse E, Bergström P, Brännström T, Siesjö P, Bergenheim AT (2017) Radiotherapy induces an immediate inflammatory reaction in malignant glioma: a clinical microdialysis study. J Neurooncol 131(1):83–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-016-2271-1

Tatekawa H, Uetani H, Hagiwara A et al (2021) Worse prognosis for IDH wild-type diffuse gliomas with larger residual biological tumor burden. Ann Nucl Med 35(9):1022–1029. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12149-021-01637-0

Janvier L, Olivier P, Blonski M et al (2015) Correlation of SUV-derived indices with tumoral aggressiveness of gliomas in static 18F-FDOPA PET: use in clinical practice. Clin Nucl Med 40(9):e429–e435. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000000897

Bund C, Heimburger C, Imperiale A et al (2017) FDOPA PET-CT of nonenhancing brain tumors. Clin Nucl Med 42(4):250–257. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000001540

Patel CB, Fazzari E, Chakhoyan A et al (2018) F-FDOPA PET and MRI characteristics correlate with degree of malignancy and predict survival in treatment-naïve gliomas: a cross-sectional study. J Neurooncol 139(2):399–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2877-6

Mayerhoefer ME, Prosch H, Beer L et al (2020) PET/MRI versus PET/CT in oncology: a prospective single-center study of 330 examinations focusing on implications for patient management and cost considerations. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 47(1):51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-019-04452-y

Ponisio MR, McConathy JE, Dahiya SM et al (2020) Dynamic. Neurooncol Pract 7(6):656–667. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npaa044

National Library of Medicine (U.S.) (2014) 18 F-DOPA- PET in Planning Surgery in Patients With Gliomas. Identifier NCT02020720. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02020720

Higgins GS (2021) [18F] FDOPA PET Imaging in Glioma: Feasibility Study for PET Guided Brain Biopsy. Identifier NCT04870580. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04870580

Funding

This work was funded by the CRUK National Cancer Imaging Translational Accelerator (C42780/A27066).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Joy Roach. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Joy Roach and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roach, J.R., Plaha, P., McGowan, D.R. et al. The role of [18F]fluorodopa positron emission tomography in grading of gliomas. J Neurooncol 160, 577–589 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04177-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04177-3