Abstract

Purpose

Spheno-orbital meningiomas are rare tumors, accounting for up to 9% of all intracranial meningiomas. Patients commonly present with proptosis, and visual deficits. These slow growing tumors are hard to resect due to extension into several anatomical compartments, resulting in recurrence rates as high as 35–50%. Although open surgical approaches have been historically used for resection, a handful of endoscopic approaches have been reported in recent years. We aimed to review the literature and describe a case of spheno-orbital meningioma with severe vision loss which was resected with an endoscopic endonasal approach achieving complete resolution of visual symptoms.

Methods

A systematic review of literature was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. PubMed, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases were queried for spheno-orbital meningiomas resected via an endoscopic endonasal approach. Furthermore, the presentation, surgical management, and post-operative outcomes of a 53-year-old female with a recurrent spheno-orbital meningioma are described.

Results

The search yielded 26 articles, of which 8 were included, yielding 19 cases. Average age at presentation was 60.5 years (range: 44–82), and 68.4% of patients were female. More than half of the cases achieved subtotal resection. Common complications associated with endoscopic endonasal surgery included CN V2 or CN V2/V3 hypoesthesia. Following surgical intervention, visual acuity and visual field remained stable or improved in the majority of the patients.

Conclusion

Endoscopic approaches are slowly gaining momentum for treatment of spheno-orbital meningiomas. Further studies on the clinical benefits of this approach on patient outcomes and post-operative complications is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common primary brain tumor, accounting for 38.3% of all central nervous system tumors, with an annual incidence rate of 8.81 per 100,000 persons in the U.S. [1]. Originally named “meningioma en plaque” by Cushing and Eisenhardt in 1938, spheno-orbital meningiomas are rare and complex tumors, accounting for up to 9% of all intracranial meningiomas [2,3,4]. Patients commonly present with symptoms including proptosis, and unilateral deficits in both visual acuity and visual field [3, 5, 6]. Ophthalmoplegia and cognitive problems can also be present in a minority of cases [5].

Spheno-orbital meningiomas are associated with significant hyperostosis of the sphenoid wing and usually extend into the orbital apex anteriorly and the cavernous sinus posteriorly with marked orbital and optic nerve compression [3, 5]. Complete resection of these tumors has been historically challenging given their extensive orbital, bony, and dural involvement, with recurrence rates of 35–50% [3, 6, 7]. A recent meta-analysis found that upwards of 90% of published studies in the literature describe using the pterional or frontotemporal craniotomy approach for resection of spheno-orbital meningiomas [5]. Although recent technological advances have made endoscopic approaches gain momentum, to date only a handful of cases have been presented that use an endoscopic approach to resect these tumors [5]. Here we describe a rare case of spheno-orbital meningioma with severe vision loss resected with an endoscopic endonasal approach achieving complete resolution of visual symptoms. Furthermore, we review the literature on all previously reported cases of spheno-orbotal meningiomas surgically managed via an endoscopic endonasal approach.

Materials and methods

Case report

Patient consent and IRB approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study formal consent or IRB approval was not required.

Literature review

A systematic review of literature was conducted in October 2021 in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig. 1). The PubMed, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases were queried using the search terms “sphenoorbital meningioma” or “spheno-orbital meningioma”, and “endonasal”. The search yielded 26 articles, 8 were found to be relevant to this review following exclusion of duplicates, review articles, articles lacking individual case data, and articles on spheno-orbital meningiomas resected using a surgical technique other than endoscopic endonasal approaches. Extracted variables from articles included demographic data, presenting symptoms, tumor characteristics including recurrence status and pathology, surgical management approach, extent of resection, post-operative complications, as well as post-operative status of visual acuity and visual field of patients.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review of the literature on spheno-orbital meningiomas resected via an endoscopic endonasal approach. (From: Moher D, Liberti A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preffered Reporting Items for Systematic Analysis: The PRISMA Statement. PLos Med 6(6): e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.)

Results

Case report

Presentation

A 53-year-old female with a history of well-controlled Behçet’s disease presented with decreased visual acuity, visual field defects, and compressive optic neuropathy in the left eye. Surgical history was notable for prior stereotactic left orbitozygomatic craniotomy and subtotal resection (STR) of a World Health Organization (WHO) grade I spheno-orbital meningioma of secretory and microcystic type, five years ago. At the time, the patient presented with afferent pupillary defect, proptosis, and progressively worsening and blurry vision in the left eye, which were all resolved following resection with visual acuity of 20/20 and color vision restored. Mild proptosis recurred a year after and is present to date. The five-year interval was unremarkable other than routine brain imaging and ophthalmology visits until the patient presented with diminished vision in the left eye.

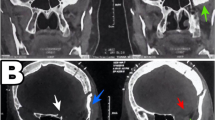

Testing showed reduced quality of vision and visual acuity with darkening of vision. Visual field was also defected in the left eye. There was no evidence of recurrent inflammatory disease associated with Behçet’s disease during ophthalmology examinations and laboratory studies. Patient also reported episodes of clear nasal drainage out of the left nostril. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed interval growth of residual tumor of the left spheno-orbital mass centered in the left middle cranial fossa with extension into the left orbital apex, cavernous sinus, skull base foramina, and masticator space (Fig. 2A, 2B). The tumor measured approximately 33 mm TR x 17 mm AP. The patient also had compressive optic neuropathy. Vision continued to decline gradually from 20/24 to 20/100 in the span of 6 months leading up to the resection.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging of the patient. (A) Pre-operative axial image demonstrates significant orbital invasion via the superior orbital fissure (B) Pre-operative coronal image demonstrating the significant lateral cavernous sinus component of the tumor (solid red arrow), tumor bulk within the pterygopalatine fossa/infraorbital space (solid blue arrow), as well as optic nerve compression (dashed red arrow) (C) Post-operative axial image demonstrating no significant debulking of the intraorbital tumor (D) Post-operative coronal image 180 degree decompression of the left optic nerve, medial to the tumor bulk (solid red arrow)

Surgical course

The patient underwent resection of the tumor using an endoscopic endonasal transpterygoid approach, and endoscopic optic nerve decompression (Supplementary Video). Following the raising of the nasoseptal flap on the patient’s right side, a left transpterygoid approach was performed to access the pterygopalatine fossa, filled by the tumor. With a 2-surgeon bimanual approach and binostril technique, STR of the tumor was achieved (Fig. 2C, 2D). The lamina papyracea was removed from the medial orbital wall, and the periorbital opened sharply to allow for orbital decompression (Fig. 3A, 3B). The nasoseptal flap was used for skull base reconstruction of the middle cranial fossa given the history of clear rhinorrhea, suspicious for cerebrospinal fluid leak [8, 9, 10]. There were no complications associated with the surgery. The pathology report found a WHO grade I meningioma of secretory type.

Intraoperative images of the transpterygoid decompression of the optic nerve and orbit. (A) Pre-decompression surgery demonstrating hyperostotic bone over the medial opticocarotid recess and optic canal (encircled). (B) Post-decompression surgery demonstrating the dura of the optic canal (grey lines), freed of the bony and tumoral compression

Post-operative course

The patient’s vision gradually improved, and a visual acuity test in last follow-up showed 20/20 vision. Preoperative visual field deficits in the left eye recovered. The patient reported new-onset cranial nerve (CN) V2 hypoesthesia over maxilla and hard palate following surgery, which has also gradually ameliorated since surgery. Her sense of taste and smell was diminished post-operatively but has since improved as reported in the last follow-up visit. The patient underwent fully fractionated intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) to 50.4 Gy for the residual tumor, with no evidence of recurrence to date.

Literature review

Our review of literature yielded 8 articles published between 2013 and 2020 on 19 cases of spheno-orbital meningiomas resected via an endoscopic endonasal approach. Patient demographics and case characteristics are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. 68.4% of patients were female and the average presenting age was 60.5 years (range: 44–82). 63.1% of patients had WHO grade I, 5.3% WHO grade II, 5.3% WHO grade III meningiomas, and the remainder of cases did not report WHO grading. 52.6% of cases comprised of recurrent meningiomas, 36.8% were primary tumors while the rest of the cases did not report on recurrence. The most common presenting symptoms were proptosis (57.9%), visual impairment (47.4%), optic neuropathy (15.8%), and CN V2/V3 hypoesthesia (10.6%). Extraoccular movement limitation, painless swelling of the left orbitotemporal region, CN III and VI nerve deficit, and midfacial numbness each presented at 5.3% amongst the patients.

In all but 1 of the cases, a combined approach was used for the resection of the tumor, which constituted of both simultaneous or secondary surgeries. The combined endoscopic endonasal approach and frontotemporal craniotomy was used in 31.6% of patients, combined endoscopic endonasal approach and transorbital approach in 31.6%, solely endoscopic endonasal approach in 5.3%, endoscopic endonasal approach with a secondary frontotempotal craniotomy in 15.8%, frontotemporal craniotomy with secondary endoscopic endonasal approach in 10.6%, and combined endoscopic endonasal and transzygomatic approach in 5.3% of cases. Gross total resection (GTR) was achieved in 15.8% of patients while 57.9% had STR, and extent of resection was not reported in the remaining patients.

The complications associated with endoscopic endonasal surgery included CN V2 hypoesthesia (10.6%), CN V2/V3 hypoesthesia (5.3%), none (47.4%), and not reported in the remainder of the cases. Post-operative visual acuity status was improved in 31.6% of cases, stable in 15.8%, stable deficit in 10.6%, worsened in 10.6%, and not reported in the rest of the cases. Post-operative visual field status was improved in 15.8% of patients, stable in 21.1%, stable deficit in 10.6%, worsened in 5.3%, and not reported for the remaining cases.

Discussion

Spheno-orbital meningiomas are rare tumors that commonly present with visual impairment and proptosis [5,6,7,8,9,10,, 11]. Although these are usually slow-growing tumors, their considerable involvement with bony, dural, and orbital structures renders their safe GTR challenging [3, 4, 6, 7, 11,12,13]. The need for significant resection of sphenoid and orbital bones further limits resection in these tumors, as it can lead to cranial deformity resulting in post-operative complications, morbidity, and mortality [3, 12]. Given that complete resection is often unattainable, residual growth and recurrence is common, with adjuvant radiotherapy and reoperation often required in management of these tumors [3, 4, 12]. Although historically open approaches, such as frontotemporal craniotomy, were used for the resection of these tumors, in recent years, minimally invasive approaches have become available [12, 14]. Open approaches provide a wider exposure to tumor tissue; however, they may be associated with functional and cosmetic post-operative complications, which can be avoided in minimally invasive techniques [12, 15]. To date, there remains no consensus surrounding the reconstruction of orbital walls following tumor resection, with proponents of bony construction deeming it a necessity to reduce the occurrence pulsatile exophthalmos [16]. A recent meta-analysis found that the pterional approach relieves visual symptoms including diplopia, ophthalmoplegia, and visual acuity and field deficits in approximately 90% of patients [5]. However, post-operative complications are commonly present with approximately 20% post-operative occurrence of hypoesthesia, ophthalmoplegia, diplopia, and ptosis in patients [5].

Minimally invasive endoscopic endonasal approaches have changed the paradigm when it comes to the management of midline skull base tumors and in select cases have been able to achieve more favorable resection and complication rates, compared to open approaches [12, 14]. Our literature review of the 19 cases of endonasal endoscopic approaches showed no post-operative complications in 75% of patients and CN V2/V3 hypoesthesia in the remaining 25%. Here we described a case of an endoscopic endonasal transpterygoid approach for surgical debulking of a spheno-orbital meningioma and optic nerve decompression resulting in complete resolution of the patient’s visual acuity and visual fields. Classically, endoscopic endonasal procedures are favored in tumors that are predominantly medial to the optic canal and carotid artery given the limitations of this technique. However, despite the significant component of the tumor lateral to the optic nerve within the cavernous sinus, this approach allowed for the bony and tumoral decompression of the optic nerve and orbit, without the morbidity of diplopia often associated with debulking tumors within the cavernous sinus and orbit. Resolution of visual symptoms was achieved despite significant residual within the cavernous sinus (Fig. 2C). Following resection, the patient reported CN V2 hypoesthesia and diminished sense of taste and smell, which were both improved in a follow-up visit four months post-operatively. The endoscopic endonasal approach has been found beneficial for optic nerve decompression as it provides excellent exposure of the medial orbital apex and the optic canal [14, 17].

Other endoscopic methods, such as the transorbital approach have also been utilized for tumors located laterally [12, 15]. The surgical approach is indeed dependent on tumor location with the endoscopic endonasal technique affording great visualization of orbital apex and optic canal and allowing resection of tumors extended to the medial optic canal, pterygopalatine fossa and the infratemporal fossa [12, 14, 15, 17]. In contrast transorbital endoscopic approaches provide good exposure of the lateral wall and orbital roof [12, 15]. It should be noted that endoscopic approaches for resection of spheno-orbital meningiomas were described fairly recently and have been used in only a handful of studies with the earliest article in our literature review published in 2013 [4]. More studies are warranted to further evaluate this approach to improve patient outcomes and post-operative complications with the goal of improving quality of life.

Conclusions

Although open surgical approaches such as frontotemporal craniotomy were the gold standard of treatment for spheno-orbital meningiomas, endoscopic approaches are slowly gaining momentum. Here we presented a successful case of spheno-orbital meningioma resection with an endoscopic endonasal approach with good outcomes. More studies are needed on the utility of endoscopic endonasal approaches for spheno-orbital meningiomas. However, in select patients, this may serve as a favorable, minimally invasive alternative with low morbidity in patients where complete tumor resection is not possible.

References

Ostrom QT, Patil N, Cioffi G et al (2020) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2013–2017. Neuro Oncol 22:iv1–iv96

Pompili A, Derome PJ, Visot A, Guiot G (1982) Hyperostosing meningiomas of the sphenoid ridge—clinical features, surgical therapy, and long-term observations: review of 49 cases. Surg Neurol 17:411–416

Shrivastava RK, Sen C, Costantino PD, Della Rocca R (2005) Sphenoorbital meningiomas: surgical limitations and lessons learned in their long-term management. J Neurosurg 103:491–497

Attia M, Patel KS, Kandasamy J et al (2013) Combined cranionasal surgery for spheno-orbital meningiomas invading the paranasal sinuses, pterygopalatine, and infratemporal fossa. World Neurosurg 80:e367–e373

Fisher FL, Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, Schoones JW et al (2021) Surgery as a safe and effective treatment option for spheno-orbital meningioma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of surgical techniques and outcomes. Acta Ophthalmol 99:26–36

Freeman JL, Davern MS, Oushy S et al (2017) Spheno-orbital meningiomas: a 16-year surgical experience. World Neurosurg 99:369–380

Boari N, Gagliardi F, Spina A et al (2013) Management of spheno-orbital en plaque meningiomas: clinical outcome in a consecutive series of 40 patients. Br J Neurosurg 27:84–90

Hadad G, Bassagasteguy L, Carrau RL et al (2006) A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: vascular pedicle nasoseptal flap. Laryngoscope 116:1882–1886

El-Sayed IH, Roediger FC, Goldberg AN et al (2008) Endoscopic reconstruction of skull base defects with the nasal septal flap. Skull base 18:385–394

Matsuda M, Akutsu H, Tanaka S, Ishikawa E (2020) Significance of the simultaneous combined transcranial and endoscopic endonasal approach for prevention of postoperative CSF leak after surgery for lateral skull base meningioma. J Clin Neurosci 81:21–26

Kong D-S, Young SM, Hong C-K et al (2018) Clinical and ophthalmological outcome of endoscopic transorbital surgery for cranioorbital tumors. J Neurosurg 131:667–675

Almeida JP, Omay SB, Shetty SR et al (2017) Transorbital endoscopic eyelid approach for resection of sphenoorbital meningiomas with predominant hyperostosis: report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg 128:1885–1895

Matsuda M, Akutsu H, Tanaka S, Matsumura A (2017) Combined simultaneous transcranial and endoscopic endonasal resection of sphenoorbital meningioma extending into the sphenoid sinus, pterygopalatine fossa, and infratemporal fossa.Surg Neurol Int8

Peron S, Cividini A, Santi L et al (2017) Spheno-orbital meningiomas: when the endoscopic approach is better.Trends Reconstr Neurosurg123–128

Dallan I, Castelnuovo P, Locatelli D et al (2015) Multiportal combined transorbital transnasal endoscopic approach for the management of selected skull base lesions: preliminary experience. World Neurosurg 84:97–107

Elborady MA, Nazim WM (2021) Spheno-orbital meningiomas: surgical techniques and results. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 57:1–9

Berhouma M, Jacquesson T, Abouaf L et al (2014) Endoscopic endonasal optic nerve and orbital apex decompression for nontraumatic optic neuropathy: surgical nuances and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 37:E19

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Farinaz Ghodrati and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Won Kim and Farinaz Ghodrati are co-first authors and contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, W., Ghodrati, F., Mozaffari, K. et al. Endoscopic endonasal approach for resection of a recurrent spheno-orbital meningioma resulting in complete resolution of visual symptoms: A case report and review of literature. J Neurooncol 160, 545–553 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04141-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04141-1