Abstract

Verbal agreement is normally in person, number and gender, but Hungarian verbs agree with their objects in definiteness instead: a Hungarian verb appears in the objective conjugation when it governs a definite object. The sensitivity of the objective conjugation suffixes to the definiteness of the object has been attributed to the supposition that they function as incorporated object pronouns (Szamosi 1974; den Dikken 2006), but we argue instead that they are agreement markers registering the object’s formal, not semantic, definiteness. Evidence comes from anaphoric binding, null anaphora (pro-drop), extraction islands, and the insensitivity of the objective conjugation to any of the factors known to condition the use of affixal and clitic pronominals. We propose that the objective conjugation is triggered by a formal definiteness feature and offer a grammar that determines, for a given complement of a verb, whether it triggers the objective conjugation on the verb. Although the objective conjugation suffixes are not pronominal, they are thought to derive historically from incorporated pronouns (Hajdú 1972), and we suggest that while referentiality and ϕ-features were largely lost, an association with topicality led to a formal condition of object definiteness. The result is an agreement marker that lacks ϕ-features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use in (short for ‘indefinite object’ or ‘intransitive’) for subjective in the glosses, and def for objective. The terms ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ are used here following Hungarian grammatical tradition, in which the terms alanyi ‘subjective’ and tárgyas ‘objective’ are used. These paradigms can also be labeled ‘indefinite’ and ‘definite’, or ‘indeterminative’ and ‘determinative’.

Coppock (2012, to appear) argues that accusative case, rather than objecthood, is relevant for determining which element the verb agrees with.

The a variant is used preceding a consonant; the az variant is used preceding a vowel.

Valamennyi can also be used with the subjective conjugation, with an indefinite meaning (É. Kiss 2000: 146), as in Ismerek valamennyi verset ‘I know[in] some poems’.

Example (23) is Kiss’s (1987) (26a).

Some scholars are reluctant to call this phenomenon “agreement”. Nikolaeva (1999: 336) writes: “In Hungarian the verbs in the objective conjugation do not actually show agreement with the object, but simply mark it for definiteness”. Siewierska (1999: 244) writes that the Hungarian objective conjugation suffixes “represent a combination of [subject agreement] and what Nichols (1992: 49) calls O[bject] registration”; on page 245 she writes: “In view of the fact that the markers of the object conjugation do not index the person or number features of the object, but merely register its presence, the object conjugation does not currently represent an instance of agreement with the object”. Corbett (2006: 91) writes: “We do not expect to have a verb which agrees in definiteness with one of its arguments”, and chooses to analyze definiteness as a condition on agreement, rather than an agreement feature, in Hungarian. Corbett continues: “Thus recognizing agreement conditions… simplifies the typology of features [by eliminating def as an agreement feature]”. We see all of these views as valid and consistent with the thesis that we argue for in this section, but we will nonetheless use the term ‘agreement’ in its wider sense for the phenomenon in question.

In contrast, the special Hungarian ending -lak/-lek seen in (10), which marks a first person singular subject and a second person object, is invariant across all tenses and moods. Some illustrative forms of vár ‘wait’ are: vár lak ‘I wait for you’; várta lak ‘I waited for you’; várná lak ‘I would wait for you’. This supports the idea that the -l in -lak/-lek is a second person clitic, as Den Dikken (2006) proposes.

By the term null anaphora we mean the null instantiation of an argument with a definite interpretation; cf. Fillmore’s (1986) ‘definite null instantiation’. We follow Austin and Bresnan (1996) in the use of the term ‘null anaphora’, which they use for anaphoric interpretations that arise independently of verbal inflection in the Australian language Jiwarli.

An anonymous reviewer points out that there are spoken varieties of Spanish and Catalan that allow 3sg clitics to double coordinations and even 3pl DPs in clitic doubling constructions (Camacho 1997: Sect. 3.1.13; Boeckx 2008: 169). This suggests that the pronominal variant of a clitic may be marked for number while the agreement (i.e. doubling) variant is not. Such an analysis for Hungarian could potentially succeed in capturing the facts under discussion, but ultimately would not be appropriate. The restriction of null anaphora to singulars is not tied to the objective conjugation, but is rather a general constraint on null anaphora.

Example (46a) would be more natural if azt and János were to exchange places, but it is still much more natural as it is than (46b), according our informants, despite the fact that there is a motivation for placing azt post-verbally in (46b).

The corresponding example with the matrix verb in the objective conjugation is also ungrammatical.

Specificity also plays a role in other constructions, including scrambling in Dutch and German, participle agreement in French and Hindi, and morphological accusative case in Turkish. See Anagnostopoulou (2005) for a summary and references.

Gutiérrez-Rexach (2000) argues that in some varieties of Spanish, the doubled DP must denote a principal filter (see Gutiérrez-Rexach 2000 and Barwise and Cooper 1981). Principal filters are a subclass of the strong determiners including quantifiers like each, every, and all, so phrases like minden fiú ‘every boy’ count as principal filters. As shown in (55), they can trigger the subjective conjugation, so principal filterhood does not make the right cut either.

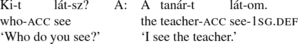

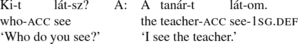

López (2009) argues that topichood is not relevant for characterizing clitic left dislocation in Spanish, and proposes that strong anaphoricity is what characterizes left dislocated items. This notion does not include all definites; for example, the teacher in the following dialogue is not anaphoric in the relevant sense (López’s example (2.35)): (i) Q: Who did you see? A: I saw the teacher. Consider the translation of this dialogue into Hungarian (using the present tense, because the subjective and objective conjugations are conflated in first person past tense): (ii) Q:

The verb is in the objective conjugation in the response in (ii), yet the object is not strongly anaphoric in López’s sense. Thus it must not be strong anaphoricity that determines the use of the objective conjugation.

There are several complications having to do with what is “visible” for haplology. First, proper names “always come with an underlying D, but the visibility of D for haplology varies with types of proper names and with dialects” (Szabolcsi 1994: 211). Second, “When there is no overt [phonological material] intervening between D and DetP, [+def] noun phrases require an overt a(z), but merely [+spec] noun phrases cannot have one” (ibid.), i.e., “the features [+def] and [+spec] differ in visibility for the haplology rule”; [+spec] is “visible” and [+def] is not. What this means is that only [−def,+spec] DetPs are visible for haplology. The set of [+def] Dets clearly contains ezen (based on Szabolcsi’s (101a)), so az ezen kalap is possible. The set of “merely [+spec]” Dets clearly contains minden, and although melyik, valamelyik, and semelyik, are “obviously definite” (ibid.: 219), they cannot be immediately preceded by az, so they must be merely [+spec]. All this means that haplology is not really a surface deletion process, which calls into question whether ‘haplology’ is the appropriate term for this process, if it exists.

Under Szabolcsi’s (1994: 219) analysis, both definites and indefinites are contained within a DP shell, the latter headed by an indefinite null determiner. Bartos (2001: 317) proposed that the DP containing the null indefinite determiner is not projected (due to Grimshaw’s 1991 notion of projectional economy), so that a structural difference between the two kinds of nominal emerges.

It is only the valamennyi of universal meaning that is specified as [def +]. See footnote 5.

Another problem with Kenesei’s (1994) analysis comes from the fact that the expletive is optional. True expletives such as the expletive subjects of raising verbs serve to satisfy a surface requirement such as the Extended Projection Principle. If the phonological material is not required in order to satisfy a surface requirement, then it is not clear why it should ever surface, assuming that it contributes nothing to the meaning.

The person and number of the possessor may also be indicated, either through the possessive suffix itself or through a separate morpheme. For example, in kalap-ja-i-m ‘my hats’, the agreement suffix -m occurs outside of the suffix indicating plural number of the possessum -i, which in turn occurs outside the possessive suffix -ja. The agreement affix is not always present; see Den Dikken (1999) for extensive discussion of this issue.

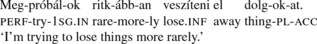

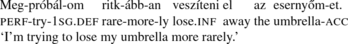

This account could potentially be extended to account for the fact that objects of embedded infinitive constructions determine the conjugation of the matrix verbs selecting the infinitive (É. Kiss 2002: 203): (i)

(ii)

These facts can be explained under the assumption that verbs are unmarked for definiteness and that they inherit the definiteness of their complement. However, verbs are not in the same extended projection as their complements so the process proposed here would have to be generalized appropriately.

In this example még…is is used to ensure that Jánostól a levelet forms a constituent (cf. É. Kiss 2000: 127).

Example (103) is É. Kiss’s (2000) ex. (15).

This evidence also speaks against the suggestion É. Kiss (2000) makes in passing to analyze dative possessors as being in the specifier of a Top[ic] projection; other topic arguments would also be predicted to fill that position.

PossP is to be distinguished from Bartos’s (1999) PossP, which is headed by the possessive suffix.

Among the issues not addressed here are various further restrictions on the co-occurrence of determiners and demonstratives, the distribution of different types of nominal, and anti-agreement phenomena in possessed noun phrases. (On the latter see especially Den Dikken (1999); and see É. Kiss (2002: Chap. 7) for an overview and synthesis.)

See Coppock and Wechsler 2010 for an explicit proposal in LFG terms.

We have no new explanation to offer for why -l is restricted to first person singular subjects. É. Kiss (2005) suggests an explanation inspired by inverse agreement systems: Hungarian object agreement is permitted only when the subject outranks the object on an animacy hierarchy in which first person singular occupies the highest position on the scale.

References

Abaffy, Erszébet E. 1991. Az ikes ragozás kialakulása: A határozott és az általános ragozás elkülönülése [The emergence of the -ik conjugation: The separation of the definite and general conjugations]. In A magyar nyelv történeti nyelvtana. 1 kötet: A korai ómagyar kor és előzményei [A historical grammar of Hungarian. Volume 1: Early Old Hungarian and its antecedents], eds. Loránd Benkő, Erszébet E. Abaffy, and Endre Rácz, 125–139. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 1994. Clitic dependencies in modern Greek. PhD diss., Salzburg University.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2005. Clitic doubling. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 519–581. Malden: Blackwell. Chap. 14.

Andrews, Avery D. 1990. Unification and morphological blocking. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 8: 507–557.

Austin, Peter, and Joan Bresnan. 1996. Non-configurationality in Australian aboriginal languages. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 14: 215–268.

Baker, Mark C. 1996. The polysynthesis parameter. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bartos, Huba. 1997. On “subjective” and “objective” agreement in Hungarian. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 44: 363–384.

Bartos, Huba. 1999. Morfoszintaxis és interpretáció: A magyar inflexiós jeleségek szintaktikai háttere [Morphosyntax and interpretation: The syntactic background to inflectional phenomena in Hungarian.]. PhD diss., ELTE, Budapest.

Bartos, Huba. 2001. Object agreement in Hungarian: A case for Minimalism. In The minimalist parameter: Selected papers from the Open Linguistics Forum, Ottawa, 21–23 March 1997, eds. Galina M. Alexandrova and Olga Arnaudova, 311–324. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Barwise, John, and Robin Cooper. 1981. Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguistics and Philosophy 4: 159–219.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2008. Aspects of the syntax of agreement. London: Routledge.

Bopp, Franz. 1842. Vergleichende Grammatik des Sanskrit, Zend, griechischen, lateinischen, litthauischen, gothischen und detschen [Comparative grammar of Sanskrit, Zend, Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Old Slavic, Gothic, and German]. Berlin: F. Dümmer.

Borer, Hagit. 1984. Parametric syntax: Case studies in Semitic and Romance languages. Dordrecht: Foris.

Bresnan, Joan. 2001. Lexical-functional syntax. Malden: Blackwell.

Bresnan, Joan, and Sam Mchombo. 1987. Topic, pronoun, and agreement in Chicheŵa. Language 63: 741–782.

Bresnan, Joan, and Lioba Moshi. 1990. Object asymmetries in comparative Bantu syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 21 (2): 147–185.

Budenz, József. 1890. Az ugor nyelvek szóragozása I. Igeragozás [The inflectional morphology of Ugric languages I. Verbs]. Nyelvtudományi Közlemények 22: 417–440.

Camacho, José Antonio. 1997. The syntax of NP coordination. PhD diss., University of Southern California.

Chisarik, Erika. 2002. Partitive noun phrases in Hungarian. In The proceedings of the LFG’02 conference, eds. Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King, 96–115. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, Gugliemo. 1990. Types of A′-dependencies. Vol. 17 of Linguistic inquiry monographs. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Comrie, Bernard. 1977. Subjects and direct objects in Uralic languages: A functional explanation of case-marking systems. Études Finno-Ourgriennes 12: 5–17.

Coppock, Elizabeth. 2012. Focus as a case position in Hungarian. Ms., Heinrich Heine University.

Coppock, Elizabeth, and Stephen Wechsler. 2010. Less-travelled paths from pronoun to agreement: The case of the Uralic objective conjugations. In The proceedings of the LFG’10 conference, ed. Tracy Holloway King, 165–185. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Corbett, Greville. 2006. Agreement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dalrymple, Mary, and Irina Nikolaeva. 2011. Objects and information structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Den Dikken, Marcel. 1999. On the structural representation of possession and agreement. In Crossing boundaries: Advances in the theory of Central and Eastern European languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Den Dikken, Marcel. 2006. When Hungarians agree (to disagree): The fine art of ‘phi’ and ‘art’. Ms., CUNY Graduate Center.

Diesing, Molly. 1992. Indefinites. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dobrovie-Sorin, Carmen. 1990. Clitic doubling, wh-movement, and quantification in Romanian. Linguistic Inquiry 21: 351–397.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 1987. Configurationality in Hungarian. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiado.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 1990. Why noun-complement clauses are barriers. In Grammar in progress, eds. J. Mascaró and M. Nespor, 265–277. Dordrecht: Foris.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2000. The Hungarian noun phrase is like the English noun phrase. In Papers from the Pécs conference, eds. Gábor Alberti and István Kenesei. Vol. 7 of Approaches to Hungarian, 121–149. Szeged: JATE Press.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2002. The syntax of Hungarian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2005. The inverse agreement constraint in Hungarian: A relic of a Uralic-Siberian Sprachbund? In Organizing grammar: Linguistic studies in honor of Henk van Riemsdijk, eds. Hans Broekhuis, Norbert Corver, Riny Huybregts, Ursula Kleinhenz, and Jan Koster. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Enç, Müvet. 1991. The semantics of specificity. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 1–25.

Evans, Nicholas. 1999. Why argument affixes in polysynthetic languages are not pronouns: Evidence from Bininj Gun-Wok. Sprachtypologie and Universalienforschung 52: 255–281.

Farkas, Donka. 2002. Specificity distinctions. Journal of Semantics 19 (3): 213–243.

Fillmore, Charles J. 1986. Pragmatically controlled zero anaphora. In Proceedings of the 12th annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, ed. Vassiliki Nikiforidou, 95–107. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Givón, Talmy. 1976. Topic, pronoun and grammatical agreement. In Subject and topic, ed. Charles N. Li, 149–188. New York: Academic Press.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1991. Extended projection. Ms., Brandeis University, Waltham, MA.

Gulya, János. 1966. Eastern Ostyak chrestomathy. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press.

Gutiérrez-Rexach, Javier. 2000. The formal semantics of clitic doubling. Journal of Semantics 16: 315–380.

Hajdú, Péter. 1968. Chrestomathia Samojedica. Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó.

Hajdú, Péter. 1972. The origins of Hungarian. In The Hungarian language, eds. Loránd Benkő and Samu Imre, 15–48. The Hague: Mouton.

Hale, Kenneth L. 2003. On the significance of Eloise Jelinek’s Pronominal Argument Hypothesis. In Formal approaches to function in grammar: In honor of Eloise Jelinek, eds. Andrew Carnie, Heidi Harley, and MaryAnn Willie, 11–43. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Havas, Ferenc. 2004. Objective conjugation and medialisation. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 51: 95–141.

Heim, Irene. 1982. The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. PhD diss., MIT.

Helimski, Eugen A. 1982. Vengersko-samodijskije lexičeskije paralleli [Hungarian-Samoyedik lexical parallels]. Moscow: Nauka.

Honti, László. 1984. Chrestomathia ostiacica [Ostyak chrestomathy]. Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó.

Honti, László. 1996. Az uráli nyelvek tárgyas ragozású igealakjainak történeti előzményéről [On the history of objective verb forms in Uralic languages]. In Ünnepi könyv Domokos Péter tiszteletére [Festschrift for Péter Domokos], eds. András Bereczki and Lásló Klima, 127–132. Budapest: ELTE BTK Finnugor Tanszék.

Honti, László. 1998. Gondolatok a mordvin tárgyas igeragozás uráli alapnyelvi hátteréről [On the Uralic background of the Mordvinian objective conjugation]. Nyelvtudományi Közlemények 96: 106–119.

Huang, Cheng-Teh James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. PhD diss., MIT.

Hunfalvy, Pál. 1862. A szmélyragok viszonyáról a birtokra és a tárgyra a magyar nyelvben [On the relation between personal endings in possessives and objects]. Nyelvtudományi Közlemények 1: 434–467.

Jaeggli, Osvaldo. 1982. Topics in Romance syntax. Dordrecht: Foris.

Jelinek, Eloise. 1984. Empty categories, case and configurationality. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 2 (1): 39–76.

Kallulli, Dalina. 2000. Direct object clitic doubling in Albanian and Greek. In Clitic phenomena in European languages, 209–248. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kálman, Béla. 1965. Vogul chresomathy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kameyama, Megumi. 1985. Zero anaphora: The case of Japanese. PhD diss., Stanford University.

Kayne, Richard S. 2008. Expletives, datives, and the tension between morphology and syntax. In The limits of syntactic variation, ed. Teresa Biberauer, 175–217. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kenesei, István. 1994. Subordinate clauses. In The syntactic structure of Hungarian, eds. Ferenc Kiefer and Katalin É. Kiss, 275–354. New York: Academic Press.

Kortvély, Erika. 2005. Verb conjugation in Tundra Nenets. Szeged: John Benjamins.

Laczkó, Tibor. 2000. On oblique arguments and adjuncts of Hungarian event nominals—A comprehensive LFG account. In The proceedings of the LFG ’00 conference, eds. Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King. Stanford: CSLI Publications. http://cslipublications.stanford.edu/LFG/5/lfg00laczko.pdf.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2002. Warlpiri: Theoretical implications. PhD diss., MIT.

Lommel, Arle R. 1998. An ergative-absolutive distinction in the Hungarian verbal complex. LACUS Forum 24: 90–99.

López, Luis. 2009. A derivational syntax for information structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marcantonio, Angela. 1985. On the definite vs. indefinite conjugation in Hungarian: A typological and diachronic analysis. Acta Linguistica Scientiarum Hungaricae 35: 267–298.

Melich, János. 1913. A magyar tárgyas igeragozás [The Hungarian objective conjugation]. Magyar Nyelv 9: 1–14.

Milsark, Gary. 1977. Toward an explanation of certain peculiarities of the existential construction in English. Linguistic Analysis 3: 1–29.

Mithun, Marianne. 2003. Pronouns and agreement: The information status of pronominal afixes. Transactions of the Philological Society 101: 235–278.

Nevins, Andrew. 2008. Phi-Interactions between Subject and Object Clitics. Presented at the 82nd Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. January, 2008.

Nichols, Joanna. 1992. Linguistic diversity in space and time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nikolaeva, Irina. 1999. Object agreement, grammatical relations, and information structure. Studies in Language 23: 331–376.

Nikolaeva, Irina. 2001. Secondary topic as a relation in information structure. Linguistics 39: 1–41.

Rédei, Károly. 1962. A tárgyas igeragozás kialakulása [The development of the objective conjugation]. Magyar Nyelv 58: 421–435.

Rédei, Károly. 1989. A finnugor igeragozásról, különös tekintettel a magyar igei személyragok eredetére [On Finno-Ugric verbal conjugation with respect to the origin of the Hungarian personal endings]. Nyelvtudományi Közlemények 90: 143–160.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1986. Null objects in Italian and the theory of pro. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 501–557.

Roberts, Ian. 2010. Agreement and head movement: Clitics, incorporation, and defective goals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rounds, Carol. 2001. Hungarian: An essential grammar. London: Routledge.

Ruwet, Nicolas. 1990. En et y: Deux clitiques pronominaux anti-logophoriques [En and y: Two anti-logophoric pronominal clitics]. Langages 97: 51–81.

Siewierska, Anna. 1999. From anaphoric pronoun to grammatical agreement marker: Why objects don’t make it. Folia Linguistica 33 (2): 225–251.

Speas, Margaret. 1990. Phrase structure in natural language. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sportiche, Dominique. 1996. Clitic constructions. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 213–276. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Steele, Susan. 1978. Word order variation: A typological study. In Syntax, eds. Joseph H. Greenberg, Charles A. Ferguson, and Edith A. Morovcsik, 585–624. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Suñer, Margarita. 1988. The role of agreement in clitic-doubled constructions. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 6: 391–434.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1994. The noun phrase. In The syntactic structure of Hungarian, eds. Ferenc Kiefer and Katalin É. Kiss, Vol. 27, 179–274. New York: Academic Press.

Szamosi, Michael. 1974. Verb-object agreement in Hungarian. In Papers from the tenth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, eds. Michael W. La Galy, Robert A. Fox, and Anthony Bruck, 701–711.

Thomsen, Vilhelm. 1912. A magyar tárgyas ragozásról néhany megjegyzés [Remarks on the Hungarian objective conjugation]. Nyelvtudományi Közlemények 41: 26–29.

Torrego, Esther. 1995a. From argumental to non-argumental pronouns: Spanish doubled reflexives. Probus 7: 221–241.

Torrego, Esther. 1995b. On the nature of clitic doubling. In Evolution and revolution in linguistic theory, eds. Hector Campos and Paula Kemchinsky, 399–418. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Uriagereka, Juan. 1988. On government. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Uriagereka, Juan. 1995. Aspects of the syntax of clitic placement in Western Romance. Linguistic Inquiry 26: 79–124.

Wald, Benji. 1979. The development of the Swahili object marker: A study of the interaction of syntax and discourse. In Discourse and syntax, ed. Talmy Givón. Vol. 12 of Syntax and semantics, 505–524. New York: Academic Press.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mark Baker, Ferenc Havas, Marcel den Dikken and three anonymous reviewers for extremely useful comments on earlier drafts, to Réka Morris, Éva Kardos and Péter Földiák for Hungarian judgments, to Fabio del Prete for judgments on Italian, to Chiyo Nishida for help with Spanish, and to Irina Nikolaeva, Anikó Lipták, Omer Preminger, Valéria Molnár, Marit Julien, and Lars Olof-Delsing for discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coppock, E., Wechsler, S. The objective conjugation in Hungarian: agreement without phi-features. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 30, 699–740 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-012-9165-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-012-9165-5