Abstract

Recently, several studies have demonstrated the role of vitamin D receptor (VDR) polymorphisms in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); however, these results are inconsistent between different cohorts. Therefore, we studied the prevalence of the VDR FokI (rs2228570), BsmI (rs1544410), ApaI (rs7975232) and TaqI (rs731236) genotypes and alleles in SLE patients (n = 258) and healthy individuals (n = 545) in a Polish population. We did not observe significant differences for either the VDR FokI, BsmI, ApaI and TaqI genotype and allele frequencies in patients with SLE and healthy individuals. However, the frequency of the VDR F/F and F/f genotypes of FokI was statistically different between patients with renal disease and patients without this symptom OR = 3.228 (1.534–6.792, p = 0.0014), p corr = 0.0476)]. There was no association of the studied VDR BsmI, ApaI and TaqI polymorphisms with clinical manifestations and laboratory profiles in patients with SLE. Our study indicates that the studied VDR FokI variant might increase the risk of some clinical presentations in patients with SLE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease for which the underlying cause remains unclear [1]. The putative causations include interactions between environmental factors, disease-prone genetic background, and various pathogen eliciting innate and adaptive immune responses [2–4]. Hyperactivation of the immune system results in the overproduction of autoantibodies and in the formation of immune complexes [1]. These immune complexes are deposited in various organs and tissues, causing the symptoms seen in the clinical manifestations of SLE [1].

Some studies have suggested the possible role of vitamin D in the development of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), type 1 diabetes (T1D), Crohn’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS) and SLE [5–7]. The primary function of the active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3], is calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism [7, 8]. In recent years, the function of vitamin D has been further studied and determined to include this molecule as a pleiotropic regulator of human physiology, as having a role in cancer chemoprevention, and as playing a role in cardio-protection and immune system modulation [7, 8].

Vitamin D transmits signals to target cells using the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is composed of both ligand binding and conserved DNA binding domains. The conserved DNA binding domains function primarily as regulators of gene transcription [9]. VDR forms heterodimers with the related retinoid X receptors and binds to DNA to initiate histone modifications, chromatin rebuilding, and RNA polymerase II binding, which is essential for initiation of transcription [10]. The VDR gene is located on chromosome 12q and contains more than 470 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), some of which modulate 1,25(OH)2D3 uptake. Therefore, these SNPs can lead to this gene’s polymorphisms to being considered as candidate disease risk variants [11]. The most commonly studied VDR SNPs include rs10735810/rs2228570 (FokI) situated in exon 2, and three SNPs in linkage disequilibrium, namely rs1544410 (BsmI) located in intron 8, rs731236 (TaqI), and rs7975232 (ApaI), the last being an SNP situated in exon 9 and intron 9 [8, 12].

Recently, several studies have demonstrated the role of VDR SNPs in the development of SLE and its clinical manifestations; however, these results are inconsistent between different cohorts [13–19]. Therefore, we aimed to study whether the FokI, BsmI, ApaI and TaqI SNPs can be a genetic risk factor of SLE in the Polish population. Because SLE is a heterogeneous disease, we also evaluated the association of these SNPs with different SLE symptoms.

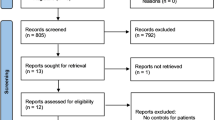

Patients and methods

Patients and controls

Two hundred and fifty-eight patients (women only) fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology Classification criteria for SLE [20, 21] were selected randomly at Institute of Rheumatology in Warsaw, Poland (Table 1). The five hundred and forty-five controls consisted of randomly selected unrelated healthy female blood donors and healthy women who had an examination at the Institute of Mother and Child in Warsaw, Poland. Both patients and control groups were of Polish Caucasian origin. The protocol of the study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee of Poznań University of Medical Sciences. Written agreement was obtained from all participating individuals. The mean age of SLE patients at diagnosis was 40 ± 11 years, and of controls 39 ± 10 years.

Genotyping

DNA was isolated from peripheral leucocytes using a standard salting out procedure. The presence of the VDR FokI (rs2228570), BsmI (rs1544410), ApaI (rs7975232) and TaqI (rs731236) SNPs was identified by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) according to the manufacturer’s instructions New England BioLabs (Ipswich, USA). DNA fragments were separated in 3 % agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Primer sequences and conditions for PCR–RFLP analyses are presented in Supplemental Table 1S. The presence of the FokI, BsmI, ApaI and TaqI polymorphisms was also confirmed by repeated PCR–RFLP analysis and commercial sequencing.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of genotypes in patients and controls was tested for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Differences in genotypic and allelic distribution between patients and controls and associations between clinical manifestations, production of antibodies (Abs), and polymorphism distribution in patients were determined by Chi-square (χ2) or Fisher exact test. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used and both p values, before (p) and after correction (p corr), were determined. The FokI and BsmI polymorphisms were tested for association with SLE using the Chi-square test for trend (p trend). The odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) were also determined. Statistical significance was interpreted as p value <0.05.

Results

Genotype analysis of the VDR FokI, BsmI, ApaI and TaqI polymorphisms did not show a significant deviation form Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the SLE and control groups.

Distribution of the VDR FokI (rs2228570) and BsmI (rs1544410) genotypes and alleles in SLE patients and healthy individuals

We observed an increased frequency of the F/F genotype in patients as compared to controls, but these differences were not significant, with OR of the F/F versus f/fgenotypes 1.300 (95 % CI = 0.840–2.010, p = 0.238) (Table 2). The frequency of the F/f genotype in patients and controls was similar at 0.44 and 0.45, respectively, and the OR for the F/f versus f/f genotypes was 1.163 (95 % CI = 0.757–1.786, p = 0.491) (Table 2). There was an increased frequency of the F/F and F/f genotypes in patients compared to controls, but these differences were also not significant OR = 1.225 (95 % CI = 0.820–1.829, p = 0.321) (Table 2).We also observed an increased frequency of the F allele in patients with SLE as compared to the control group; however, these differences were not significant, OR = 1.146 (95 % CI = 0.924–1.421, p = 0.215). The p value of the Chi-square test for the trend observed for the FokI polymorphism was also not statistically significant (p trend = 0.232).

There was also no contribution of the VDR BsmI polymorphism to SLE. The frequency of the BB genotype was lower in patients with SLE compared to the control group, but not significantly so. OR of the B/B versus b/b genotypes was 0.683 (95 % CI = 0.419–1.111, p = 0.123). We found an increase in B/b heterozygote frequency in patients than in controls, but these differences were also not significant, OR of B/b versus b/b genotype was 0.988 (95 % CI = 0.719–1.356, p = 0.939) (Table 2). The frequency of the B/B or B/b genotypes was slightly lower in SLE patients, OR of B/B or B/b versus b/b was 0.9113 (95 % CI = 0.675–1.231, p = 0.545) (Table 2). We also did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of B alleles between patients and controls. OR for the VDRB allele frequency was 0.869 (95 % CI = 0.698–1.083, p = 0.211). The p value of the Chi-square test for the trend observed for the BsmI polymorphism was also not statistically significant (p trend = 0.271).

Distribution of the VDR ApaI (rs7975232) and TaqI (rs731236) genotypes and alleles in SLE patients and healthy individuals

We did not observe an association of the VDR ApaI and TaqI SNPs with SLE. OR of the A/A versus a/a genotypes was 1.126 (95 % CI = 0.750–1.689, p = 0.568). There was a slight decrease in A/a heterozygote frequency in patients than in controls, OR of A/a versus a/a genotype was 1.007 (95 % CI = 0.695–1.460, p = 0.970) (Table 2). The frequency of the A/A or A/a genotypes was slightly increased in SLE patients, OR of A/A or A/a versus a/a was 1.051 (95 % CI = 0.744–1.485, p = 0.777) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of A alleles between patients and controls. OR for the VDR A allele frequency was 1.068 (95 % CI = 0.866–1.317, p = 0.541). The p value of the Chi-square test for the trend observed for the ApaI polymorphism was also not statistically significant (p trend = 0.5533) (Table 2).

There was also no contribution of the VDR TaqI polymorphism to SLE. The frequency of the TT genotype was slightly increased in SLE patients than in the control group. OR of the T/T versus t/t genotype was 1.440 (95 % CI = 0.884–2.345, p = 0.142). We also observed a slight increase in T/t heterozygote frequency in patients than in controls, OR of T/t versus t/t genotype was 1.429 (95 % CI = 0.883–2.312, p = 0.145) (Table 2). The frequency of the T/T or T/t genotypes was also slightly increased in SLE patients, OR of T/T or T/t versus t/t was 1.434 (95 % CI = 0.907–2.267, p = 0.121) (Table 2). We also did not find a significant difference in the prevalence of T alleles between patients and controls. OR for the VDR T allele frequency was 1.140 (95 % CI = 0.916–1.420, p = 0.240). The p value of the Chi-square test for the trend observed for the TaqI polymorphism was also not statistically significant (p trend = 0.2417).

Association of the VDR FokI (rs2228570), BsmI (rs1544410), ApaI (rs7975232) and TaqI (rs731236) polymorphisms with clinical symptoms of SLE

Since previous studies indicated the association of VDR polymorphisms to some clinical SLE manifestations [13–19], we evaluated their contribution to clinical manifestations present in the patient group we studied. We found a significant association between the F/F and F/f allele with renal manifestations of SLE OR = 3.228 (1.534–6.792, p = 0.0014), p corr = 0.0476) (Fig. 1; Table 2S, on line supplementary data). However, we did not observe a significant association of the BsmI, ApaI and TaqI polymorphisms with clinical manifestations in patients (Figs. 2, 3, 4; Tables 3S–5S, online supplementary data). There was also no association of either of the studied polymorphisms with the presence of anti-dsDNA, anti–Smith, anti-snRNP, anti-Ro, anti-Scl-70 or anti-phospholipid Abs (not shown).

Odds ratio plot for comparison of genotypes VDR F/F + F/f versus f/f and F/F versus F/f + f/f between patients with and patients without a particular manifestation. Each OR value is represented by the corresponding black square or circle with arms representing 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). The analysis was performed by χ2 test. The black circle indicates a significant association

Odds ratio plot for comparison of genotypes VDR B/B + b/B versus b/b and B/B versus b/B + b/b between patients with and patients without a particular manifestation. Each OR value is represented by the corresponding black square with arms representing 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). The analysis was performed by χ2 test

Odds ratio plot for comparison of genotypes VDR A/A + A/a versus a/a and A/A versus A/a + a/a between patients with and patients without a particular manifestation. Each OR value is represented by the corresponding black square or circle with arms representing 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). The analysis was performed by χ2 test

Odds ratio plot for comparison of genotypes VDR T/T + T/t versus t/t and T/T versus t/T + t/t between patients with and patients without a particular manifestation. Each OR value is represented by the corresponding black square with arms representing 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). The analysis was performed by χ2 test

Discussion

The immune system in patients with SLE is characterized by an enhanced humoral response and decreased T cell cytotoxicity [22–24]. Immune cells exhibit abnormal signaling, defective gene expression, and changes in cytokine production [22–24]. Vitamin D functions to regulate various immune cells, and an abnormal vitamin D level has been documented in SLE patients in various populations [25–31]. Low vitamin D levels were associated with higher disease activity in Malaysian, Egyptian, Chinese, Israeli and European cohorts [27–31]. The decline of vitamin D concentration in SLE patients was associated with the presence of aortic stiffness, leucopenia, renal disease, increased anti-C1q and anti-dsDNA titers, dyslipidemia and increased cardiovascular risk [29, 30, 32–34]. Recently, Birmingham et al. [35] suggested that a seasonal decrease in vitamin D levels may trigger an SLE flare in non-African Americans. The role of vitamin D in the development of SLE has also been studied in the murine model. Administration of 1,25(OH)2D3 to mice with SLE resulted in a protective role in the development of this autoimmune disease [36].

Studies performed in vitro have demonstrated that vitamin D inhibits T cell proliferation and leads to a reduced production of interferon-gamma(IFN-γ),interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-6, IL-12, IL-23 and IL-17 [37–40]. Moreover, the immunosuppressive activity of 1,25(OH)2D3 is demonstrated by an inhibition in the maturation, differentiation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells, leading to T cell hyporesponsiveness [41]. VDR have been found in monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and effector/memory T cells [25]. This suggests that functional polymorphisms in the VDR gene may modulate the immune system and an individual’s susceptibility to developing SLE.

We did not find that the FokI, BsmI, ApaI and TaqI polymorphisms are associated with an individual’s susceptibility to SLE in a Polish population. Our observations are consistent with the findings of Monticielo et al. [18], who demonstrated no association of the BsmI and FokI polymorphisms with the development of SLE in a Brazilian-European cohort. There was also no association of the FokI VDR polymorphism with Chinese SLE patients in Taiwan, or of the BsmI VDR polymorphism with SLE in Iranian and Thai populations [15–17]. However, the BB genotype of the BsmI VDR SNP was found to be a risk factor of SLE in Taiwanese and Japanese populations [13, 14]. In addition to these findings, Luo et al. [19] observed a significantly increased frequency of the B allele in SLE patients from a Han Chinese population.

In our study, SLE patients with the F/F and F/f genotypes of the FokI VDR polymorphism exhibited a significantly increased risk of developing renal disease. However, we did not find an association of the BsmI VDR polymorphism with clinical manifestations of SLE. There was no association between the BsmI polymorphism and clinical manifestations, laboratory profiles, or lupus nephritisin Chinese SLE patients in Taiwan [14]. However, the VDR B allele was associated with the development of nephritis in a Han Chinese population, and the bb genotype was associated with lupus nephritis in a Japanese population [13, 19].

The differences observed between the BsmI and FokI VDR polymorphisms and the susceptibility to SLE development and the occurrence of some clinical manifestations may be due to exposure of the analysed groups to different environmental factors, group size and genetic heterogeneity.

The roles of the BsmI and FokI polymorphisms on the function of the VDR receptor have been already determined in several studies [12, 18, 19]. Arai et al. [12] demonstrated that the FokI polymorphism located in exon 2 is linked to a second methionine start site, leading to the formation of a shorter protein receptor that has greater transcriptional activity than the wild type receptor. Recently, Monticielo et al. [18] reinforced the functional role of the FokI polymorphism. They demonstrated that vitamin D concentration was significantly increased in individuals with the f/f genotype versus patients having the F/F genotype [18]. The BsmI polymorphism can be linked to a variable-length polyadenylate sequence within the 3′-untranslated region [8]. Recently, Luo et al. [19] demonstrated that the level of VDR mRNA was significantly decreased in patients with the VDR B allele versus those not bearing the B allele.

The BsmI and/or FokI VDR polymorphisms have also been recognized as risk factors of some other autoimmune diseases, including RA, Behçet’s, Graves’ and Addison’s diseases, psoriasis, MS, T1D, and others [42–48]. Moreover, both of these polymorphisms have been determined to be risk factors for colorectal, breast, prostate, and other cancers [11].

Our study did not demonstrate that the FokI, BsmI, ApaI and TaqI VDR SNPs are risk factors of SLE in the Polish population, but we found an association of the FokI polymorphism with renal manifestations in SLE patients. However, to study the detailed role of these SNPs in SLE, this evaluation should be replicated in other independent cohorts.

References

Sekigawa I, Naito T, Hira K, Mitsuishi K, Ogasawara H, Hashimoto H, Ogawa H (2004) Possible mechanisms of gender bias in SLE: a new hypothesis involving a comparison of SLE with atopy. Lupus 13:217–222

Jönsen A, Bengtsson AA, Nived O, Truedsson L, Sturfelt G (2007) Gene-environment interactions in the aetiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity 40:613–617

Burzynski M, Duriagin S, Mostowska M, Wudarski M, Chwalinska-Sadowska H, Jagodzinski PP (2007) MTR 2756 A > G polymorphism is associated with the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in the Polish population. Lupus 16:450–454

Wong M, Tsao BP (2006) Current topics in human SLE genetics. Springer Semin Immunopathol 28:97–107

Muller K, Kriegbaum NJ, Baslund B, Sorensen OH, Thyman M, Bentzen K (1995) Vitamin D3 metabolism in patients with rheumatic diseases: low serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 14:397–400

Schwalfenberg GK (2012) Solar radiation and vitamin D: mitigating environmental factors in autoimmune disease. J Environ Public Health 2012:619381

Maruotti N, Cantatore FP (2010) Vitamin D and the immune system. J Rheumatol 37:491–495

Uitterlinden AG, Fang Y, Van Meurs JB, Pols HA, Van Leeuwen JP (2004) Genetics and biology of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms. Gene 338:143–156

Miyamoto K, Kesterson RA, Yamamoto H, Taketani Y, Nishiwaki E, Tatsumi S, Inoue Y, Morita K, Takeda E, Pike JW (1997) Structural organization of the human vitamin D receptor chromosomal gene and its promoter. Mol Endocrinol 11:1165–1179

Zhang J, Chalmers MJ, Stayrook KR, Burris LL, Wang Y, Busby SA, Pascal BD, Garcia-Ordonez RD, Bruning JB, Istrate MA, Kojetin DJ, Dodge JA, Burris TP, Griffin PR (2011) DNA binding alters coactivator interaction surfaces of the intact VDR-RXR complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18:556–563

McCullough ML, Bostick RM, Mayo TL (2009) Vitamin D gene pathway polymorphisms and risk of colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer. Annu Rev Nutr 29:111–132

Arai H, Miyamoto K-I, Taketani Y, Yamamoto H, Iemori Y, Morita K, Tonai T, Nishisho T, Mori S, Takeda E (1997) A vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in the translation initiation codon: effect on protein activity and relation to bone mineral density in Japan women. J Bone Miner Res 12:915–921

Ozaki Y, Nomura S, Nagahama M, Yoshimura C, Kagawa H, Fukuhara S (2000) Vitamin-D receptor genotype and renal disorder in Japanese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nephron 85:86–91

Huang CM, Wu MC, Wu JY, Tsai FJ (2002) Association of vitamin D receptor gene BsmI polymorphisms in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 11:31–34

Huang CM, Wu MC, Wu JY, Tsai FJ (2002) No association of vitamin D receptor gene start codon fok 1 polymorphisms in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 29:1211–1213

Sakulpipatsin W, Verasertniyom O, Nantiruj K, Totemchokchyakarn K, Lertsrisatit P, Janwityanujit S (2006) Vitamin D receptor gene BsmI polymorphisms in Thai patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 8:R48

Abbasi M, Rezaieyazdi Z, Afshari JT, Hatef M, Sahebari M, Saadati N (2010) Lack of association of vitamin D receptor gene BsmI polymorphisms in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int 30:1537–1539

Monticielo OA, Brenol JC, Chies JA, Longo MG, Rucatti GG, Scalco R, Xavier RM (2012) The role of BsmI and FokI vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in Brazilian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 21:43–52

Luo XY, Yang MH, Wu FX, Wu LJ, Chen L, Tang Z, Liu NT, Zeng XF, Guan JL, Yuan GH (2012) Vitamin D receptor gene BsmI polymorphism B allele, but not BB genotype, is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Han Chinese population. Lupus 21:53–59

Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ (1982) The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 25:1271–1277

Hochberg MC (1997) Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40:1725

Januchowski R, Wudarski M, Chwalińska-Sadowska H, Jagodzinski PP (2008) Prevalence of ZAP-70, LAT, SLP-76, and DNA methyltransferase 1 expression in CD4+ T cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 27:21–27

Moulton VR, Tsokos GC (2011) Abnormalities of T cell signaling in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 13:207

Gröndal G, Gunnarsson I, Rönnelid J, Rogberg S, Klareskog L, Lundberg I (2000) Cytokine production, serum levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol 18:565–570

Veldman CM, Cantorna MT, DeLuca HF (2000) Expression of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor in the immune system. Arch Biochem Biophys 374:334–338

Provvedini DM, Tsoukas CD, Deftos LJ, Manolagas SC (1983) 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in human leukocytes. Science 221:1181–1183

Yeap SS, Othman AZ, Zain AA, Chan SP (2012) Vitamin D levels: its relationship to bone mineral density response and disease activity in premenopausal Malaysian systemic lupus erythematosus patients on corticosteroids. Int J Rheum Dis 15:17–24

Hamza RT, Awwad KS, Ali MK, Hamed AI (2011) Reduced serum concentrations of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in Egyptian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: relation to disease activity. Med Sci Monit 17:CR711–CR718

Mok CC, Birmingham DJ, Ho LY, Hebert LA, Song H, Rovin BH (2012) Vitamin D deficiency as marker for disease activity and damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison with anti-dsDNA and anti-C1q. Lupus 21:36–42

Mok CC, Birmingham DJ, Leung HW, Hebert LA, Song H, Rovin BH (2012) Vitamin D levels in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship with disease activity, vascular risk factors and atherosclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51:644–652

Amital H, Szekanecz Z, Szücs G, Dankó K, Nagy E, Csépány T, Kiss E, Rovensky J, Tuchynova A, Kozakova D, Doria A, Corocher N, Agmon-Levin N, Barak V, Orbach H, Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y (2010) Serum concentrations of 25-OH vitamin D in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are inversely related to disease activity: is it time to routinely supplement patients with SLE with vitamin D? Ann Rheum Dis 69:1155–1157

Reynolds JA, Haque S, Berry JL, Pemberton P, Teh LS, Ho P, Gorodkin R, Bruce IN (2012) 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with increased aortic stiffness in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51:544–551

Bogaczewicz J, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, Arkuszewska C, Zabek J, Kontny E, McCauliffe D, Wozniacka A (2012) Vitamin D status in systemic lupus erythematosus patients and its association with selected clinical and laboratory parameters. Lupus 21:477–484

Wu PW, Rhew EY, Dyer AR, Dunlop DD, Langman CB, Price H, Sutton-Tyrrell K, McPherson DD, Edmundowicz D, Kondos GT, Ramsey-Goldman R (2009) 25-hydroxyvitamin D and cardiovascular risk factors in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 61:1387–1395

Birmingham DJ, Hebert LA, Song H, Noonan WT, Rovin BH, Nagaraja HN, Yu CY (2012) Evidence that abnormally large seasonal declines in vitamin D status may trigger SLE flare in non-African Americans. Lupus. doi:10.1177/0961203312439640

Lemire JM, Ince A, Takashima M (1992) 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 attenuates the expression of experimental murine lupus of MRL/l mice. Autoimmunity 12:143–148

D’Ambrosio D, Cippitelli M, Cocciolo MG, Mazzeo D, Di Lucia P, Lang R, Sinigaglia F, Panina-Bordignon P (1998) Inhibition of IL-12 production by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Involvement of NF-kappa B downregulation in transcriptional repression of the p40 gene. J Clin Invest 101:252–262

Alroy I, Towers TL, Freedman LP (1995) Transcriptional repression of the interleukin-2 gene by vitamin D3: direct inhibition of NFATp/AP-1 complex formation by a nuclear hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol 15:5789–5799

Cippitelli M, Santoni A (1998) Vitamin D3: a transcriptional modulator of the interferon-gamma gene. Eur J Immunol 28:3017–3030

Daniel C, Sartory NA, Zahn N, Radeke HH, Stein JM (2008) Immune modulatory treatment of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid colitis with calcitriol is associated with a change of a T helper (Th) 1/Th17 to a Th2 and regulatory T cell profile. J Pharmacol ExpTher 324:23–33

Penna G, Adorini L (2000) 1 Alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J Immunol 164:2405–2411

Karray EF, Ben Dhifallah I, Ben Abdelghani K, Ben Ghorbel I, Khanfir M, Houman H, Hamzaoui K, Zakraoui L (2012) Associations of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms FokI and BsmI with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis and Behçet’s disease in Tunisians. Joint Bone Spine 79:144–148

Panierakis C, Goulielmos G, Mamoulakis D, Petraki E, Papavasiliou E, Galanakis E (2009) Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 1 diabetes in Crete, Greece. Clin Immunol 133:276–281

Ramos-Lopez E, Kurylowicz A, Bednarczuk T, Paunkovic J, Seidl C, Badenhoop K (2005) Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms are associated with Graves’ disease in German and Polish but not in Serbian patients. Thyroid 15:1125–1130

Panierakis C, Goulielmos G, Mamoulakis D, Petraki E, Papavasiliou E, Galanakis E (2009) Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 1 diabetes in Crete, Greece. Clin Immunol 133:276–281

Pani MA, Seissler J, Usadel KH, Badenhoop K (2002) Vitamin D receptor genotype is associated with Addison’s disease. Eur J Endocrinol 147:635–640

Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG (2012) Vitamin D receptor ApaI, TaqI, BsmI, and FokI polymorphisms and psoriasis susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 39:6471–6478

Tajouri L, Ovcaric M, Curtain R, Johnson MP, Griffiths LR, Csurhes P, Pender MP, Lea RA (2005) Variation in the vitamin D receptor gene is associated with multiple sclerosis in an Australian population. J Neurogenet 19:25–38

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant No 502-01-01124182-07474, Poznań University of Medical Sciences. The technical assistance of Ms. Alicja Pinczewskais gratefully acknowledged.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mostowska, A., Lianeri, M., Wudarski, M. et al. Vitamin D receptor gene BsmI, FokI, ApaI and TaqI polymorphisms and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Mol Biol Rep 40, 803–810 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-012-2118-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-012-2118-6