Abstract

The most widely used model for granular gases is perhaps the inelastic hard-sphere model (IHSM), where the grains are assumed to be perfectly smooth spheres colliding with a constant coefficient of normal restitution. A much more tractable model is the inelastic Maxwell model (IMM), in which the velocity-dependent collision rate is replaced by an effective mean-field constant. This simplification has been taken advantage of by many researchers to find a number of exact results within the IMM. On the other hand, both the IHSM and IMM neglect the impact of roughness—generally present in real grains—on the dynamic properties of a granular gas. This is remedied by the inelastic rough hard-sphere model (IRHSM), where, apart from the coefficient of normal restitution, a constant coefficient of tangential restitution is introduced. In parallel to the simplification carried out when going from the IHSM to the IMM, we propose in this paper an inelastic rough Maxwell model (IRMM) as a simplification of the IRHSM. The tractability of the proposed model is illustrated by the exact evaluation of the collisional moments of first and second degree, and the most relevant ones of third and fourth degree. The results are applied to the evaluation of the rotational-to-translational temperature ratio and the velocity cumulants in the homogeneous cooling state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Granular gases are typically modeled as a system of agitated inelastic hard spheres [1,2,3]. In the basic inelastic hard-sphere model (IHSM) of granular gases, the particles are assumed to be smooth (i.e., with no rotational degrees of freedom) and the collisions are characterized by a constant coefficient of normal restitution, \(0<\alpha \le 1\). If the number density of the gas is low enough, the most relevant physical quantity is the one-particle velocity distribution function (VDF), which obeys the Boltzmann equation appropriately adapted to incorporate the inelastic nature of collisions. Nevertheless, the fact that the collision rate in the IHSM is proportional to the relative velocity of the two colliding particles prevents the associated collisional moments from being expressible in terms of a finite number of velocity moments, thus hampering the possibility of deriving analytical results.

The above difficulty is also present for molecular gases (where collisions are elastic, i.e., \({\alpha }=1\)). In that case, it can be overcome by assuming that the gas is made of Maxwell molecules, that is, particles interacting via a repulsive force inversely proportional to the fifth power of distance [3,4,5,6,7,8]. This makes the collision rate independent of the relative velocity, so that the collisional moments become bilinear combinations of velocity moments of the same or lower degree. If collisions are inelastic (\({\alpha }<1\)), one can still construct the so-called inelastic Maxwell model (IMM) by assuming an effective mean-field collision rate independent of the velocity [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

The original IHSM and the simpler IMM capture many of the most relevant features of granular gases [2, 45]. On the other hand, both models leave out the roughness of real grains, which gives rise to frictional collisions and energy transfer between the translational and rotational degrees of freedom. A convenient way of modeling this roughness effect is by augmenting the IHSM by means of a constant coefficient of tangential restitution \(-1\le \beta \le 1\) [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] The resulting granular-gas model can be referred to as the inelastic rough hard-sphere model (IRHSM). Needless to say, the IRHSM is even much more difficult to tackle with than the IHSM of frictionless, smooth particles. Therefore, in order to incorporate the influence of roughness and the associated rotational degrees of freedom on the dynamical properties and yet have a tractable model, it seems natural to construct an inelastic rough Maxwell model (IRMM), which would play a role with respect to the IRHSM similar to that played by the well-known IMM with respect to the IHSM (see Fig. 1). To the best of our knowledge, such an IRMM has not been proposed or worked out before.

The aim of this paper is to construct a tractable IRMM and illustrate its main features by evaluating exactly all the collisional velocity moments of first and second degree, as well as the most relevant ones of third and fourth degree. As expected, the results reduce to the known ones in the smooth limit (IMM) [41,42,43,44]. We also display the results for the conservative case of elastic and perfectly rough particles (\({\alpha }={\beta }=1\)), what constitutes the Maxwell analog of the Pidduck gas [90]. Moreover, we apply the exact knowledge of the isotropic second- and fourth-degree collisional moments to the study of the homogeneous cooling state (HCS), as described by the model.

The organization of the paper is as follows. In Sect. 2, after summarizing the collision rules and the basic properties of the Boltzmann equation for a granular gas of inelastic and rough particles, and recalling the IRHSM, our IRMM is written down. The core of the paper is presented in Sect. 3, where the exact structure of the collisional moments is displayed in Table 1, the explicit expressions of the coefficients in terms of inelasticity and roughness being moved to Appendix A, while some particularizations and consistency tests are shown in Appendix B. Next, Sect. 4 is devoted to the application of the results to the HCS. Finally, the paper is closed in Sect. 5 with some concluding remarks.

2 Kinetic Theory of Inelastic and Rough Particles

We consider a granular gas made of inelastic and rough particles of diameter \(\sigma \), mass m, and moment of inertial \(I= (m\sigma ^2/4)\kappa \), where the dimensionless moment of inertia ranges from \(\kappa =0\) (mass concentrated at the center of the sphere) to a maximum value \(\kappa =\frac{2}{3}\) (mass concentrated at the spherical surface), the value \(\kappa =\frac{2}{5}\) corresponding to a uniform mass distribution.

2.1 Collision Rules

Let us denote by \(\mathbf {v}\) and \(\varvec{\omega }\) the translational and angular velocities, respectively, and introduce the short-hand notation \(\{\mathbf {v},\varvec{\omega }\}\rightarrow \varvec{\xi }\) and \(d\mathbf {v}d\varvec{\omega }\rightarrow d\varvec{\xi }\). A direct encounter between two particles 1 and 2 is characterized by the precollisional velocities \((\varvec{\xi }_1; \varvec{\xi }_2)\), the postcollisional velocities \((\varvec{\xi }_1'; \varvec{\xi }_2')\), and the collision unit vector \(\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}=(\mathbf {r}_2-\mathbf {r}_1)/\sigma \) joining the centers of the two colliding particles. The pre- and postcollisional velocities are related by

where \({\mathbf {Q}}\) is the impulse exerted by particle 1 on particle 2. The relative velocity of the points of the spheres at contact during a collision is \(\overline{\mathbf {g}}=\mathbf {g}-{\sigma \over 2}\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}\times (\varvec{\omega }_1+\varvec{\omega }_2)\), where \(\mathbf {g}=\mathbf {v}_1-\mathbf {v}_2\) denotes the center-of-mass relative velocity; a similar relation holds for \(\overline{\mathbf {g}}'\).

In the most basic model, an inelastic collision of two rough particles is characterized by

where \(0<\alpha \le 1\) and \(-1\le \beta \le 1\) are the coefficients of normal and tangential restitution, respectively. For an elastic collision of perfectly smooth particles one has \(\alpha =1\) and \(\beta =-1\), while \(\alpha =1\) and \(\beta =1\) for an elastic encounter of perfectly rough particles.

It is possible to show that Eqs. (2) imply [2, 79]

where

Equations (1) and (3) express the postcollisional velocities in terms of the precollisional velocities and of the collision vector [91].

For a restitution encounter, the pre- and postcollisional velocities are denoted by \((\varvec{\xi }_1^*; \varvec{\xi }_2^*)\) and \((\varvec{\xi }_1; \varvec{\xi }_2)\), respectively, and the collision vector by \(\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}^*=-\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}\). One then has

2.2 Boltzmann Equation

Assuming molecular chaos, and in the absence of external forces or torques, the Boltzmann equation for granular gases is given by

where \(f(\mathbf {r},\varvec{\xi }, t)\) is the one-particle VDF and \(J[\varvec{\xi }\vert f,f]\) is the bilinear collision operator. Quite generally, it can be written as

where use has been made of Eq. (5) and, as usual, the notation \(f_1=f(\varvec{\xi }_1)\), \(f_2=f(\varvec{\xi }_2)\), \(f_1^*=f(\varvec{\xi }_1^*)\), \(f_2^*=f(\varvec{\xi }_2^*)\) has been employed. Moreover, the function \(\mathcal {F}(x)\) is proportional to the collision rate, its precise form defining the chosen kinetic model.

The so-called weak form of the Boltzmann equation is obtained by multiplying both sides of Eq. (6) by an arbitrary trial function \(\Psi (\mathbf {r},\varvec{\xi },t)\) and integrating over \(\varvec{\xi }\). This yields

where

is the local number density,

is the local average value of \(\Psi \), and

is the collisional production term of \(\Psi \), with the conventional notation \(\Psi _1=\Psi (\varvec{\xi }_1)\), \(\Psi _2=\Psi (\varvec{\xi }_2)\), \(\Psi _1'=\Psi (\varvec{\xi }_1')\), \(\Psi _2'=\Psi (\varvec{\xi }_2')\). In the second step of Eq. (11), we have used the relationships (5) and the standard symmetry properties of the collision term.

In particular, the flow velocity (\(\mathbf {u}\)), the mean angular velocity (\(\varvec{\Omega }\)), and the granular temperatures (\(T_t\), \(T_r\), and T) correspond to \(\Psi =\mathbf {v}\), \(\Psi =\varvec{\omega }\), \(\Psi =V^2\), \(\Psi =\omega ^2\), and \(\Psi =mV^2+I\omega ^2\), respectively, where \(\mathbf {V}=\mathbf {v}-\mathbf {u}\) denotes the peculiar velocity. Thus,

The associated collisional production terms can be written as [79, 84]

This defines the “de-spinning” rate coefficient \(\zeta _\Omega \), the energy production rates \(\zeta _t\) and \(\zeta _r\), and the cooling rate \(\zeta \). Moreover, \(\theta \equiv T_r/T_t\) is the rotational-to-translational temperature ratio.

2.3 The Inelastic Rough Hard-Sphere Model (IRHSM)

If the gas is modeled by the IRHSM, one has \(\mathcal {F}(x)=\Theta (x)x\), where \(\Theta (x)\) is the Heaviside step function. In that case, the collision operator becomes

where the subscript (\(+\)) in the integration over \(\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}\) denotes the constraint \(\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}\cdot \mathbf {g}>0\) and we have taken into account that \(\Theta (\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}^*\cdot \mathbf {g}^*)(\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}^*\cdot \mathbf {g}^*)=\alpha ^{-1}\Theta (\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}\cdot \mathbf {g})(\widehat{\varvec{\sigma }}\cdot \mathbf {g})\). Analogously, Eq. (11) becomes

If \(\Psi (\varvec{\xi })\) is a polynomial and thus \(\langle \Psi \rangle \) is a velocity moment, the collisional moment \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {HS}}[\Psi ]\) involves the full VDF or, equivalently, all the higher-degree moments. As a consequence, the infinite hierarchy of moments given by Eq. (8) cannot be solved, even in spatially uniform states, unless an approximate closure is applied. For instance, if f is approximated by a two-temperature Maxwellian, one finds [2, 75, 84]

2.4 The Inelastic Rough Maxwell Model (IRMM)

The problem mentioned below Eq. (15) is also present in the conventional case of elastic collisions. However, if the collision rate is assumed to be a constant (Maxwell model), the collisional moments involve moments of a degree equal to or lower than the degree of the moment \(\langle \Psi \rangle \) [3, 5,6,7,8].

We now apply the same philosophy to a granular gas of inelastic and rough particles and propose the IRMM by choosing \(\mathcal {F}(x)=\text {const}\) in Eq. (7), i.e.,

where \(\nu _{\text {M}}\) is an effective collision frequency. Analogously, Eq. (11) becomes

3 Collisional Moments

Using the collision rules (1) and (3) in Eq. (18), it is possible to evaluate the collisional moments in terms of velocity moments. After some tedious work, we obtained all the collisional moments of first and second degree, plus the most relevant ones of third and fourth degree. Their structure is shown in Table 1, where the expected result \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\mathbf {V}]=0\) (momentum conservation) is not included. This yields a total number of 13 independent collisional moments and 60 dimensionless coefficients.

We have adopted the following criterion for the notation of the coefficients. Let us first denote by \(\Psi _{k_1k_2}(\varvec{\xi })=\Psi _{k_1}^{(1)}(\mathbf {V})\Psi _{k_2}^{(2)}(\varvec{\omega })\) a homogeneous velocity polynomial of degrees \(k_1\) and \(k_2\) with respect to \(\mathbf {V}\) and \(\varvec{\omega }\), respectively, i.e., \(\Psi _{k_1}^{(1)}(\lambda \mathbf {V})=\lambda ^{k_1}\Psi _{k_1}^{(1)}(\mathbf {V})\) and \(\Psi _{k_2}^{(2)}(\lambda \varvec{\omega })=\lambda ^{k_2}\Psi _{k_2}^{(2)}(\varvec{\omega })\). Then, a coefficient of the form \(Y_{k_1 k_2\mid \ell _1\ell _2}\) (with \(k_1+k_2=\ell _1+\ell _2\)) corresponds to the collisional moment \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{k_1k_2}]\) and accompanies a product of the form \(\langle \Psi _{i_1i_2}(\varvec{\xi })\rangle \langle \Psi _{j_1j_2}(\varvec{\xi })\rangle \) with \(i_1+j_1=\ell _1\) and \(i_2+j_2=\ell _2\). When, for a given \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{k_1k_2}]\), more than a coefficient of the form \(Y_{k_1 k_2\mid \ell _1\ell _2}\) exists, each one of them is distinguished by a superscript. A coefficient of the form \(Y_{k_1 k_2\mid k_1k_2}\) or \(Y_{k_1 k_2\mid k_1k_2}^{(1)}\) is a diagonal one because it couples \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{k_1k_2}]\) to \(\langle \Psi _{k_1k_2}(\varvec{\xi })\rangle \). Finally, we use the Greek letters \(Y=\chi \), \(Y=\varphi \), and \(Y=\psi \) for the coefficients in \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{k_1k_2}]\) associated with scalar, vector, and tensor quantities \(\Psi _{k_1k_2}(\varvec{\xi })\), respectively; moreover, an overline is used if the definition of \(\Psi _{k_1k_2}(\varvec{\xi })\) contains the inner product \(\mathbf {V}\cdot \varvec{\omega }\).

It must be remarked that the results for \(\Psi _{01}(\varvec{\xi })=\varvec{\omega }\), \(\Psi _{20}(\varvec{\xi })=V^2\), and \(\Psi _{02}(\varvec{\xi })=\omega ^2\) are also valid in the case of a hybrid model where \(\mathcal {F}(x)=\text {const}\times \Theta (x)\). However, this does not happen in the case of the other quantities in Table 1, that is, the associated collisional moments cannot be expressed only in terms of velocity moments of the same or lower degree if \(\mathcal {F}(x)=\text {const}\times \Theta (x)\).

The exact explicit expressions for the 60 coefficients appearing in Table 1 in terms of \(\widetilde{\alpha }\), \(\widetilde{\beta }\), and \(\kappa \) are given in Appendix A. The particularization of the coefficients to the IMM (\({\alpha }<1\), \({\beta }=-1\)) and to the Pidduck model (\({\alpha }={\beta }=1\)) [90] is presented in Appendix B, where some consistency tests are performed.

The basic production rates are those defined by Eqs. (13). According to Table 1,

where in the second equalities we have made use of Eqs. (A1, A2 and A4).

Comparison with the approximate results for the IRHSM, Eqs. (16), shows that the choices \(\nu _{\text {M}}=\frac{5}{4}\nu _\text {HS}\) and \(\nu _{\text {M}}=\frac{5}{2}\nu _\text {HS}\) are directly related to inelasticity and roughness, respectively. Thus, in comparison with the IRHSM, the IRMM lessens the impact of inelasticity on energy dissipation, relative to the impact of roughness. As a consequence, there is no a unique choice for \(\nu _{\text {M}}\) allowing for an agreement between the IRHSM and IRMM basic production rates for arbitrary \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \). This is reminiscent of the inability of the Bhatnagar–Gross–Krook (BGK) kinetic model to reproduce the Boltzmann shear viscosity and thermal conductivity with a single collision frequency [92].

A way of circumventing the impossibility of matching Eqs. (16 and 19) with a unique relationship between \(\nu _\text {HS}\) and \(\nu _{\text {M}}\) consists of choosing \(\nu _{\text {M}}=\frac{5}{4}\nu _\text {HS}\) and then assuming the following mapping between the coefficients of normal restitution in the IRHSM (\(\alpha _{\text {HS}}\)) and the IRMM (\(\alpha _{\text {M}}\)): \(1-\alpha _{\text {M}}^2=2(1-\alpha _{\text {HS}}^2)\). For instance, \(\alpha _{\text {M}}=0.4\), 0.6, 0.8, and 1 would correspond to \(\alpha _{\text {HS}}=0.76\), 0.82, 0.91, and 1, respectively. Table 2 summarizes the consequences of the two main choices \(\nu _{\text {M}}=\frac{5}{4}\nu _\text {HS}\) and \(\nu _{\text {M}}=\frac{5}{2}\nu _\text {HS}\).

Alternatively, and in analogy with a BGK-like model for the IRHSM [93], one can replace the IRMM collision operator (17) by

This modified IRMM keeps being amenable to an exact evaluation of the associated collisional moments and, in addition, allows one to recover Eqs. (16) if \(\nu _{\text {M}}=\frac{5}{4}\nu _\text {HS}\). More specifically, only the diagonal coefficients are affected by the modification (20): \(Y_{k_1k_2\mid k_1k_2}\rightarrow Y_{k_1k_2\mid k_1k_2}+k_1\gamma \) and \(Y_{k_1k_2\mid k_1k_2}^{(1)}\rightarrow Y_{k_1k_2\mid k_1k_2}^{(1)}+k_1\gamma \).

On the other hand, in this paper we restrict ourselves to the IRMM as defined by Eq. (17), that is, without the extra term appearing in Eq. (20). The reason is that we regard the IRMM as a mathematical model on its own and not necessarily as a model intended to mimic the properties of the IRHSM, for which alternative approximate tools are already available [2, 75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89].

4 Application to the Homogeneous Cooling State (HCS)

In the absence of gradients or any external driving, Eq. (8) becomes

For sufficiently long times, the system asymptotically reaches the HCS, which is characterized by a uniform, isotropic, and stationary scaled VDF [2, 84]

In particular, \(X\rightarrow 0\) and \(\dot{\theta }\rightarrow 0\). The latter condition implies \(\zeta _t-\zeta _r\rightarrow 0\), which yields the HCS temperature ratio

with \(c=1\). As expected from the discussion in Sect. 3, in the case of the IRHSM, the two-temperature Maxwellian approximation [see Eqs. (16)] also yields Eqs. (23), except that \(c=2\) [2, 84].

Figure 2 shows the \(\beta \)-dependence of the temperature ratios \(T_r/T_t\) and \(T_r/T\) for uniform particles (\(\kappa =\frac{2}{5}\)) and several representative values of the coefficient of normal restitution. We observe that, except in the case of elastic collisions (\({\alpha }=1\)), \(T_r/T_t\rightarrow \infty \) and, hence, \(T_r/T\rightarrow 2\) in the quasi-smooth limit (\({\beta }\rightarrow -1\)).

The scaled fourth-degree moments are \(\langle c^4\rangle =\frac{9}{4} \langle V^4\rangle /\langle V^2\rangle ^2\), \(\langle w^4\rangle =\frac{9}{4}\langle \omega ^4\rangle /\langle \omega ^2\rangle ^2\), \(\langle c^2w^2\rangle =\frac{9}{4}\langle V^2\omega ^2\rangle /\langle V^2\rangle \langle \omega ^2\rangle \), and \(\langle (\mathbf {c}\cdot \mathbf {w})^2\rangle =\frac{9}{4}\langle (\mathbf {V}\cdot \varvec{\omega })^2\rangle /\langle V^2\rangle \langle \omega ^2\rangle \). Assuming the stationary VDF \(\phi (\mathbf {c},\mathbf {w})\) has not been reached yet, the evolution equations for those moments are

The departure of the HCS scaled VDF \(\phi (\mathbf {c},\mathbf {w})\) from the Maxwellian \(\pi ^{-3}e^{-c^2-w^2}\) can be measured by the four cumulants [80,81,82,83]

In terms of those cumulants, Eqs. (24) can be recast as

where the elements of the matrices \(\mathsf {M}\) and \(\mathsf {L}\) are

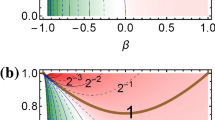

a Plot of the smallest eigenvalue \(\mu _{\min }\) as a function of \({\beta }\) for \(\kappa =\frac{2}{5}\) and \(\alpha = 0.4\) (—), 0.6 (–\(\cdot \)–), 0.8 (– –), and 1 (\(\cdots \)). The circles denote the location of the threshold value (\(\beta _0\)) below which \(\mu _{\min }<0\). b Plot of \(\beta _0\) as a function of \(\alpha \) for \(\kappa =\frac{2}{5}\). The fourth-degree moments diverge in the region below the curve.

The time evolution of the cumulants is characterized by the eigenvalues of the matrix \(\mathsf {M}\), the asymptotic behavior being governed by the smallest eigenvalue, \(\mu _{\min }\). If \(\mu _{\min }>0\), the cumulants relax to their finite stationary values \(\left[ a_{20}^{(0)},a_{02}^{(0)},a_{11}^{(0)},a_{00}^{(1)}\right] ^\dagger =-\mathsf {M}^{-1}\cdot \mathsf {L}\). On the other hand, if \(\mu _{\min }<0\) then the cumulants diverge. Figure 3a shows the \({\beta }\)-dependence of \(\mu _{\min }\) for the same representative values of \({\alpha }\) as in Fig. 2. We observe that, at a given \({\alpha }<1\), there exists a threshold value \({\beta }_0\) such that \(\mu _{\min }<0\) if \({\beta }<{\beta }_0\). The \({\alpha }\)-dependence of \({\beta }_0\) is shown in Fig. 3b. For the pairs \(({\alpha },{\beta })\) below the curve in Fig. 3b, the cumulants, and hence the fourth-degree moments, diverge. This divergence is likely associated with an algebraic high-velocity tail of the VDF, as already present in the case of the IMM [34,35,36,37,38, 41,42,43,44].

If the particles are perfectly smooth (\({\beta }=-1\)), the temperature ratio \(\theta \) is irrelevant and all the matrix elements vanish except \(M_{11}=\frac{1}{120}(1+{\alpha })^2(5+6{\alpha }-3{\alpha }^2)\), \(M_{33}=\frac{1}{20}(1+{\alpha })^2\), \(M_{43}=\frac{1}{36}(1+{\alpha })^2\), \(M_{44}=\frac{1}{9}(1+{\alpha })^2\), and \(L_1=-\frac{1}{20}(1-{\alpha }^2)^2\). This implies that \(a_{02}^{(0)}\) is arbitrary, \(a_{11}^{(0)}=a_{00}^{(1)}=0\), and \(a_{20}^{(0)}=6(1-{\alpha })^2/(5+6{\alpha }-3{\alpha }^2)\). The latter result agrees with a previous derivation for the IMM [39].

On the other hand, in the special case of the Pidduck gas (\({\alpha }={\beta }=1\)), the HCS reduces to equilibrium and Eqs. (23) yield \(\theta =1\), as expected. Moreover, from Eqs. (B15 and B16), one gets \(\mathsf {L}=0\), implying that the cumulants (25) vanish in that case.

Plot of the cumulants a \(a_{20}^{(0)}\), b \(a_{02}^{(0)}\), c \(a_{11}^{(0)}\), and d \(a_{00}^{(1)}\) as functions of \({\beta }\) for \(\kappa =\frac{2}{5}\) and \(\alpha = 0.4\) (—), 0.6 (–\(\cdot \)–), 0.8 (– –), and 1 (\(\cdots \)). The vertical lines denote the asymptotes at \({\beta }={\beta }_0\).

Apart from the IMM and the equilibrium Pidduck gas, in the general case with \({\alpha }<1\) and \(\mid {\beta }\mid <1\), the stationary values of the cumulants are given, as said above, by \(\left[ a_{20}^{(0)},a_{02}^{(0)},a_{11}^{(0)},a_{00}^{(1)}\right] ^\dagger =-\mathsf {M}^{-1}\cdot \mathsf {L}\), provided that \({\beta }>{\beta }_0\). The \({\beta }\)-dependence of the four cumulants are displayed in Fig. 4 for the same choices of \({\alpha }\) as in Figs. 2 and 3a. The positivity of \(a_{11}^{(0)}\) implies that high translational velocities are strongly correlated to high angular velocities [80,81,82,83]. In turn, the negative values of \(a_{00}^{(1)}\) mean that quasinormal orientations between the translational and angular velocity vectors tend to be favored against quasiparallel orientations (“lifted-tennis-ball” effect) [76,77,78, 80,81,82,83].

5 Conclusions

In this work, we have worked out a simple Maxwell model (IRMM) by keeping the collision rules of inelastic rough hard spheres but, on the other hand, assuming an effective mean-field collision rate independent of the relative velocity of the colliding pair. The latter assumption allows one to express a collisional moment of degree k as a bilinear combination of velocity moments of degrees \(i\le k\) and \(j\le k\) with \(i+j\), as happens in the well-known IMM (smooth particles) [42,43,44]. Nevertheless, the derivation of exact results in the IRMM is much more complicated than in the IMM. Not only are the translational and rotational degrees of freedom entangled, thus increasing the number and structure of the moments, but also the coefficients in the bilinear combinations are functions of the coefficient of normal restitution (as in the IMM) and, additionally, of the coefficient of tangential restitution and the reduced moment of inertia.

Specifically, we have considered the moments of first and second degree, the moments of third degree related to the heat flux, and the isotropic fourth-degree moments. The structure of the associated collisional moments is displayed in Table 1. The number of coefficients is 60, since in some cases a common coefficient factorizes more than one product of moments. The exact expressions of those 60 coefficients in terms of the two coefficients of restitution (\({\alpha }\) and \({\beta }\)) and of the reduced moment of inertia (\(\kappa \)) are presented in Appendix A. We have checked that the coefficients satisfy some consistency tests. First, they reduce to the expressions reported in the literature in the smooth limit (\({\beta }=-1\)) [42,43,44]. Next, when particularized to elastic and perfectly rough particles (Pidduck model, \({\alpha }={\beta }=1\)), the coefficients obey a number of relations needed to allow the equilibrium VDF to be an exact solution of the model.

The knowledge of the collisional moments stemming from the IRMM is not constrained to a specific physical situation and, thus, it can be exploited in several applications. Here we have applied the results to the HCS. Specifically, the rotational-to-translational temperature ratio has been found [see Eqs. (23)] and the linear evolution equations for the fourth-degree cumulants have been obtained [see Eq. (26)]. Interestingly, we have found that those cumulants diverge in time if, at a given \({\alpha }\), the coefficient of tangential restitution lies below a threshold value \({\beta }_0({\alpha })\) [see Fig. 3]. This reflects the existence of an algebraic high-velocity tail of the VDF, reminiscent of the case of the IMM [34,35,36,37,38, 41]. If \({\beta }>{\beta }_0({\alpha })\), the exact stationary cumulants have been obtained (see Fig. 4). In general, the departure of the HCS VDF from the equilibrium one is rather strong: (a) the (marginal) translational and angular VDFs exhibit large excess kurtoses, (b) high translational velocities are correlated to high angular velocities, and (c) the translational and angular velocities tend to adopt quasi-normal orientations (“lifted-tennis-ball” effect).

It must be stressed that, in analogy to the relationship between the IHSM and the IMM, the IRMM is proposed here as a mathematical model and not as an approximation of the IRHSM. In this respect, the predictions obtained analytically from the IRMM do not need to be interpreted strictly as a quantitative replacement for the results obtained either numerically or by simulations from the IRHSM. On the other hand, the IRMM provides a tractable toy model that can be used to cleanly unveil nontrivial physical properties, guide the construction of approximations to the IRHSM, and serve as a benchmark for numerical or simulation approaches. Notwithstanding this, a closer contact with the IRHSM can be provided by the augmented IRMM defined by Eq. (20).

Relying on the set of collisional moments displayed in Table 1 with coefficients given in Appendix A, further applications of the model are envisioned. In particular, the Navier–Stokes transport coefficients can be exactly derived. Preliminary results show the existence of a new “spin” viscosity coefficient, which was overlooked in previous Sonine approximations of the IRHSM [84, 88, 89]. In addition, the exact non-Newtonian rheological properties of a granular gas under simple shear flow can also be obtained. The results of both applications will be published elsewhere.

References

Brilliantov, N.V., Pöschel, T.: Kinetic Theory of Granular Gases. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2004)

Garzó, V.: Granular Gaseous Flows. A Kinetic Theory Approach to Granular Gaseous Flows. Springer, Cham (2019)

Kremer, G.M.: An Introduction to the Boltzmann Equation and Transport Processes in Gases. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Maxwell, J.C.: IV. On the dynamical theory of gases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. (London) 157, 49–88 (1867). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1867.0004

Truesdell, C., Muncaster, R.G.: Fundamentals of Maxwell’s Kinetic Theory of a Simple Monatomic Gas. Academic Press, New York (1980)

Ernst, M.H.: Nonlinear model-Boltzmann equations and exact solutions. Phys. Rep. 78, 1–171 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(81)90002-8

Garzó, V., Santos, A.: Kinetic Theory of Gases in Shear Flows: Nonlinear Transport. Fundamental Theories of Physics. Springer, Dordrecht (2003)

Santos, A.: Solutions of the moment hierarchy in the kinetic theory of Maxwell models. Cont. Mech. Thermodyn. 21, 361–387 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00161-009-0113-5

Bobylev, A.V., Carrillo, J.A., Gamba, I.M.: On some properties of kinetic and hydrodynamic equations for inelastic interactions. J. Stat. Phys. 98, 743–773 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018627625800

Carrillo, J.A., Cercignani, C., Gamba, I.M.: Steady states of a Boltzmann equation for driven granular media. Phys. Rev. E 62, 7700–7707 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.62.7700

Ben-Naim, E., Krapivsky, P.L.: Multiscaling in inelastic collisions. Phys. Rev. E 61, R5–R8 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.61.R5

Cercignani, C.: Shear flow of a granular material. J. Stat. Phys. 102, 1407–1415 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004804815471

Ben-Naim, E., Krapivsky, P.L.: In Granular Gas Dynamics, Lecture Notes. In: Pöschel, T., Luding, S. (eds.) Physics, vol. 624, pp. 65–94. Springer, Berlin (2003)

Bobylev, A.V., Cercignani, C.: Self-similar asymptotics for the Boltzmann equation with inelastic and elastic interactions. J. Stat. Phys. 110, 333–375 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021031031038

Bobylev, A.V., Cercignani, C., Toscani, G.: Proof of an asymptotic property of self-similar solutions of the Boltzmann equation for granular materials. J. Stat. Phys. 111, 403–417 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022273528296

Santos, A., Ernst, M.H.: Exact steady-state solution of the Boltzmann equation: a driven one-dimensional inelastic Maxwell gas. Phys. Rev. E 68, 011305 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.68.011305

Garzó, V.: Nonlinear transport in inelastic Maxwell mixtures under simple shear flow. J. Stat. Phys. 112, 657–683 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023828109434

Brito, R., Ernst, M:. In: Korutcheva, E., Cuerno, R. (eds.) Advances in Condensed Matter and Statistical Mechanics, pp. 177–202. Nova Science Publishers, New York (2004)

Garzó, V., Astillero, A.: Transport coefficients for inelastic Maxwell mixtures. J. Stat. Phys. 118, 935–971 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10955-004-2006-0

Bisi, M., Carrillo, J.A., Toscani, G.: Decay rates in probability metrics towards homogeneous cooling states for the inelastic Maxwell model. J. Stat. Phys. 124, 625–653 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10955-006-9035-9

Bobylev, A.V., Gamba, I.M.: Boltzmann equations for mixtures of Maxwell gases: exact solutions and power like tails. J. Stat. Phys. 124, 497–516 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10955-006-9044-8

Bolley, F., Carrillo, J.A.: Tanaka theorem for inelastic Maxwell models. Commun. Math. Phys. 276, 287–314 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00220-007-0336-x

Carrillo, J.A., Toscani, G.: Contractive probability metrics and asymptotic behavior of dissipative kinetic equations. Riv. Mat. Univ. Parma 7(6), 75–198 (2007)

Garzó, V.: Shear-rate dependent transport coefficients for inelastic Maxwell models. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 40, 10729–10767 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/40/35/002

Bobylev, A.V., Cercignani, C., Gamba, I.M.: Generalized Kinetic Maxwell Mmodels of Granular Gases, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 1937, pp. 23–58. Springer, Berlin (2008)

Bobylev, A.V., Cercignani, C., Gamba, I.M.: On the self-similar asymptotics for generalized non-linear kinetic Maxwell models. Commun. Math. Phys. 291, 599–644 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00220-009-0876-3

Carlen, E.A., Carrillo, J.A., Carvalho, M.C.: Strong convergence towards homogeneous cooling states for dissipative Maxwell models. Ann. I. H. Poincaré Anal Non-linéaire 26, 167–1700 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anihpc.2008.10.005

Garzó, V., Trizac, E.: Rheological properties for inelastic Maxwell mixtures under shear flow. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 165, 932–940 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2010.01.016

Furioli, G., Pulvirenti, A., Terraneo, E., Toscani, G.: Convergence to self-similarity for the Boltzmann equation for strongly inelastic Maxwell molecules. Ann. I. H. Poincaré Anal Non-linéaire 27, 719–737 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anihpc.2009.11.005

Brey, J.J., de Soria, M.I.G., Maynar, P.: Breakdown of hydrodynamics in the inelastic Maxwell model of granular gases. Phys. Rev. E 82, 021303 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.82.021303

Khalil, N., Garzó, V., Santos, A.: Hydrodynamic Burnett equations for inelastic Maxwell models of granular gases. Phys. Rev. E 89, 052201 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.89.052201

Gómez González, R., Garzó, V.: Simple shear flow in granular suspensiones: inelastic Maxwell models and BGK-type kinetic model. J. Stat. Mech. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/aaf719

Khalil, N., Garzó, V.: Unified hydrodynamic description for driven and undriven inelastic Maxwell mixtures at low density. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 53, 355002 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8121/ab9f72

Baldassarri, A., Marconi, U.M.B., Puglisi, A.: Influence of correlations on the velocity statistics of scalar granular gases. Europhys. Lett. 58, 14–20 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2002-00600-6

Ben-Naim, E., Krapivsky, P.L.: Scaling, multiscaling, and nontrivial exponents in inelastic collision processes. Phys. Rev. E 66, 011309 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.66.011309

Krapivsky, P.L., Ben-Naim, E.: Nontrivial velocity distributions in inelastic gases. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 35, L147–L152 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/35/11/103

Ernst, M.H., Brito, R.: High-energy tails for inelastic Maxwell models. Europhys. Lett. 58, 182–187 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2002-00622-0

Ernst, M.H., Brito, R.: Scaling solutions of inelastic Boltzmann equations with over-populated high energy tails. J. Stat. Phys. 109, 407–432 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020437925931

Santos, A.: Transport coefficients of \(d\)-dimensional inelastic Maxwell models. Physica A 321, 442–466 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4371(02)01005-1

Santos, A., Garzó, V.: Simple shear flow in inelastic Maxwell models. J. Stat. Mech. (2007). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2007/08/P08021

Ernst, M.H., Brito, R.: Driven inelastic Maxwell models with high energy tails. Phys. Rev. E 65, 040301 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.65.040301

Garzó, V., Santos, A.: Third and fourth degree collisional moments for inelastic Maxwell model. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 40, 14927–14943 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/40/50/002

Garzó, V., Santos, A.: Hydrodynamics of inelastic Maxwell models. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 6(4), 37–76 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1051/mmnp/20116403

Santos, A., Garzó, V.: Collisional rates for the inelastic Maxwell model. Application to the divergence of anisotropic high-order velocity moments in the homogeneous cooling state. Granul. Matter 14, 105–110 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10035-012-0336-1

Goldhirsch, I.: Rapid granular flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 35, 267–293 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fluid.35.101101.161114

Jenkins, J.T., Richman, M.W.: Kinetic theory for plane flows of a dense gas of identical, rough, inelastic, circular disks. Phys. Fluids 28, 3485–3494 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.865302

Lun, C.K.K., Savage, S.B.: A simple kinetic theory for granular flow of rough, inelastic, spherical particles. J. Appl. Mech. 54, 47–53 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3172993

Campbell, C.S.: The stress tensor for simple shear flows of a granular material. J. Fluid Mech. 203, 449–473 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089001540

Lun, C.K.K.: Kinetic theory for granular flow of dense, slightly inelastic, slightly rough spheres. J. Fluid Mech. 233, 539–559 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112091000599

Lun, C.K.K., Bent, A.A.: Numerical simulation of inelastic frictional spheres in simple shear flow. J. Fluid Mech. 258, 335–353 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112094003356

Goldshtein, A., Shapiro, M.: Mechanics of collisional motion of granular materials. Part 1. General hydrodynamic equations. J. Fluid Mech. 282, 75–114 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112095000048

Luding, S.: Granular materials under vibration: simulations of rotating spheres. Phys. Rev. E 52, 4442–4457 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.52.4442

Lun, C.K.K.: Granular dynamics of inelastic spheres in Couette flow. Phys. Fluids 8, 2868–2883 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.869068

Zamankhan, P., Tafreshi, H.V., Polashenski, W., Sarkomaa, P., Hyndman, C.L.: Shear induced diffusive mixing in simulations of dense Couette flow of rough, inelastic hard spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 4487–4491 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.477076

McNamara, S., Luding, S.: Energy nonequipartition in systems of inelastic, rough spheres. Phys. Rev. E 58, 2247–2250 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.58.2247

Luding, S., Huthmann, M., McNamara, S., Zippelius, A.: Homogeneous cooling of rough, dissipative particles: theory and simulations. Phys. Rev. E 58, 3416–3425 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.58.3416

Herbst, O., Huthmann, M., Zippelius, A.: Dynamics of inelastically colliding spheres with Coulomb friction: relaxation of translational and rotational energy. Granul. Matter 2, 211–219 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00010915

Aspelmeier, T., Huthmann, M., Zippelius, A.: In: Pöschel, T., Luding, S. (eds.) Granular Gases, Lectures Notes In Physics, vol. 564, pp. 31–58. Springer, Berlin (2001)

Jenkins, J.T., Zhang, C.: Kinetic theory for identical, frictional, nearly elastic spheres. Phys. Fluids 14, 1228–1235 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1449466

Polashenski, W., Zamankhan, P., Mäkiharju, S., Zamankhan, P.: Fine structures in sheared granular flows. Phys. Rev. E 66, 021303 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.66.021303

Cafiero, R., Luding, S., Herrmann, H.J.: Rotationally driven gas of inelastic rough spheres. Europhys. Lett. 60, 854–860 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2002-00295-7

Mitarai, N., Hayakawa, H., Nakanishi, H.: Collisional granular flow as a micropolar fluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 174301 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.174301

Viot, P., Talbot, J.: Thermalization of an anisotropic granular particle. Phys. Rev. E 69, 051106 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.69.051106

Goldhirsch, I., Noskowicz, S.H., Bar-Lev, O.: Nearly smooth granular gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 068002 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.068002

Goldhirsch, I., Noskowicz, S.H., Bar-Lev, O.: Hydrodynamics of nearly smooth granular gases. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 21449–21470 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0532667

Zippelius, A.: Granular gases. Physica A 369, 143–158 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2006.04.012

Piasecki, J., Talbot, J., Viot, P.: Angular velocity distribution of a granular planar rotator in a thermalized bath. Phys. Rev. E 75, 051307 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.75.051307

Cornu, F., Piasecki, J.: Granular rough sphere in a low-density thermal bath. Physica A 387, 4856–4862 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2008.03.014

Santos, A.: Homogeneous free cooling state in binary granular fluids of inelastic rough hard spheres. AIP Conf. Proc. 1333, 128–133 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3562637

Vega Reyes, F., Lasanta, A., Santos, A., Garzó, V.: Thermal properties of an impurity immersed in a granular gas of rough hard spheres. EPJ Web Conf. 140, 04003 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201714004003

Vega Reyes, F., Lasanta, A., Santos, A., Garzó, V.: Energy nonequipartition in gas mixtures of inelastic rough hard spheres: the tracer limit. Phys. Rev. E 96, 052901 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.96.052901. Erratum: 100, 049901 (2019)

Garzó, V., Santos, A., Kremer, G.M.: Impact of roughness on the instability of a free-cooling granular gas. Phys. Rev. E 97, 052901 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.97.052901

Torrente, A., López-Castaño, M.A., Lasanta, A., Vega Reyes, F., Prados, A., Santos, A.: Large Mpemba-like effect in a gas of inelastic rough hard spheres. Phys. Rev. E 99, 060901 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.99.060901

Gómez González, R., Garzó, V.: Non-Newtonian rheology in inertial suspensions of inelastic rough hard spheres under simple shear flow. Phys. Fluids 32, 073315 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0015241

Huthmann, M., Zippelius, A.: Dynamics of inelastically colliding rough spheres: relaxation of translational and rotational energy. Phys. Rev. E 56, R6275–R6278 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.56.R6275

Brilliantov, N.V., Pöschel, T., Kranz, W.T., Zippelius, A.: Translations and rotations are correlated in granular gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 128001 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.128001

Kranz, W.T., Brilliantov, N.V., Pöschel, T., Zippelius, A.: Correlation of spin and velocity in the homogeneous cooling state of a granular gas of rough particles. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 179, 91–111 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2010-01196-0

Rongali, R., Alam, M.: Higher-order effects on orientational correlation and relaxation dynamics in homogeneous cooling of a rough granular gas. Phys. Rev. E 89, 062201 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.89.062201

Santos, A., Kremer, G.M., Garzó, V.: Energy production rates in fluid mixtures of inelastic rough hard spheres. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 184, 31–48 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.184.31

Santos, A., Kremer, G.M., dos Santos, M.: Sonine approximation for collisional moments of granular gases of inelastic rough spheres. Phys. Fluids 23, 030604 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3558876

Vega Reyes, F., Santos, A., Kremer, G.M.: Role of roughness on the hydrodynamic homogeneous base state of inelastic spheres. Phys. Rev. E 89, 020202 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.89.020202

Vega Reyes, F., Santos, A., Kremer, G.M.: Properties of the homogeneous cooling state of a gas of inelastic rough particles. AIP Conf. Proc. 1628, 494–501 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4902634

Vega-Reyes, F., Santos, A.: Steady state in a gas of inelastic rough spheres heated by a uniform stochastic force. Phys. Fluids 27, 113301 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4934727

Kremer, G.M., Santos, A., Garzó, V.: Transport coefficients of a granular gas of inelastic rough hard spheres. Phys. Rev. E 90, 022205 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.90.022205

Santos, A.: Interplay between polydispersity, inelasticity, and roughness in the freely cooling regime of hard-disk granular gases. Phys. Rev. E 98, 012904 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.98.012904

Megías, A., Santos, A.: Driven and undriven states of multicomponent granular gases of inelastic and rough hard disks or spheres. Granul. Matter 21, 49 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10035-019-0901-y

Megías, A., Santos, A.: Energy production rates of multicomponent granular gases of rough particles. A unified view of hard-disk and hard-sphere systems. AIP Conf. Proc. 2132, 080003 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5119584

Megías, A., Santos, A.: Hydrodynamics of granular gases of inelastic and rough hard disks or spheres. I. Transport coefficients. Phys. Rev. E 104, 034901 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.104.034901

Megías, A., Santos, A.: Hydrodynamics of granular gases of inelastic and rough hard disks or spheres. II. Stability analysis. Phys. Rev. E 104, 034902 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.104.034902

Pidduck, F.B.: The kinetic theory of a special type of rigid molecule. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 101, 101–112 (1922). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1922.0028

For an interactive animation, see A. Santos, “Inelastic Collisions of Two Rough Spheres”. Wolfram Demonstrations Project. https://www.demonstrations.wolfram.com/InelasticCollisionsOfTwoRoughSpheres/ (2010)

Cercignani, C.: The Boltzmann Equation and Its Applications. Springer, New York (1988)

Santos, A.: A Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook-like model kinetic equation for a granular gas of inelastic rough hard spheres. AIP Conf. Proc. 1333, 41–48 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3562623

Acknowledgements

A.S. acknowledges financial support from Grant PID2020-112936GB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and from grants IB20079 and GR21014 funded by Junta de Extremadura (Spain) and by ERDF “A way of making Europe.” G.M.K. is grateful to the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for financial support through Grant No. 304054/2019-4.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Eric A. Carlen.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Explicit Expressions for the Coefficients Appearing in Table 1

The 60 coefficients appearing in Table 1 are given by

Appendix B: Consistency Tests

Tables 3, 4, 5 display the expressions of the 60 coefficients in two interesting situations: (i) inelastic and perfectly smooth particles (i.e., the IMM, \({\alpha }<1\), \({\beta }=-1\)) and (ii) elastic and perfectly rough particles (i.e., the Pidduck model, \({\alpha }={\beta }=1\)). Let us use both situations (i) and (ii) as tests of the results.

1.1 2.1. Inelastic Maxwell Model (IMM)

In case (i), 45 out of the 60 coefficients vanish. First, the angular velocities are unaffected by collisions and thus \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{0k_2}]=0\) because \(\Psi _{0k_2}(\varvec{\xi })\) is a function of \(\varvec{\omega }\) only. This implies that the 12 coefficients of the form \(Y_{0k_2\mid \ell _1\ell _2}\) identically vanish.

Also, since \(\Psi _{k_10}(\varvec{\xi })\) is a function of \(\mathbf {V}\) only, \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{k_10}]\) cannot be coupled to moments involving the angular velocity, so that \(Y_{k_10\mid \ell _1\ell _2}=0\) if \(\ell _2\ne 0\) (6 coefficients).

Next, the angular and translational velocities are uncorrelated and, therefore, \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{k_1k_2}]=\langle \Psi _{k_2}^{(2)}(\varvec{\omega })\rangle \mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi _{k_1}^{(1)}]\) and \(\langle \Psi _{k_1k_2}(\varvec{\xi })\rangle =\langle \Psi _{k_1}^{(1)}(\mathbf {V})\rangle \langle \Psi _{k_2}^{(2)}(\varvec{\omega })\rangle \). This justifies the vanishing of the remaining 27 coefficients, as well as the relations

Equations (B14a and B14b) imply \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[V^2\omega ^2]=\langle \omega ^2\rangle \mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[V^2]\) and \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[(\mathbf {V}\cdot \varvec{\omega })^2]=\langle \varvec{\omega }\varvec{\omega }\rangle :\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\mathbf {V}\mathbf {V}]\), respectively.

Finally, the coefficients \(\chi _{20\mid 20}\), \(\psi _{20\mid 20}\), \(\varphi _{30\mid 30}\), \(\chi _{40\mid 40}^{(1)}\), \(\chi _{40\mid 40}^{(2)}\), and \(\chi _{40\mid 40}^{(3)}\) agree with previous results for the IMM [2, 39, 40, 42,43,44].

1.2 2.2. Pidduck Model

In case (ii) the total energy is conserved by collisions, i.e., \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[mV^2+I\omega ^2]=0\). This is guaranteed by the relations

Other tests in case (ii) correspond to the fact that \(\mathcal {J}_{\text {M}}[\Psi ]=0\) for any \(\Psi (\varvec{\xi })\) if the system is at equilibrium, in which case all the anisotropic moments vanish and \(\langle \omega ^2\rangle =\frac{m}{I}\langle V^2\rangle =\frac{4}{\kappa \sigma ^2}\langle V^2\rangle \), \(\langle V^2\omega ^2\rangle =3\langle \left( \mathbf {V}\cdot \varvec{\omega }\right) ^2\rangle =\langle V^2\rangle \langle \omega ^2\rangle \), \(\langle V^4\rangle =\frac{5}{3}\langle V^2\rangle ^2\), and \(\langle \omega ^4\rangle =\frac{5}{3}\langle \omega ^2\rangle ^2\). Therefore, according to Table 1, one should have

From the expressions in Tables 3, 4, 5 one can check that Eqs. (B16) are indeed satisfied.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kremer, G.M., Santos, A. Granular Gas of Inelastic and Rough Maxwell Particles. J Stat Phys 189, 23 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10955-022-02984-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10955-022-02984-6