Abstract

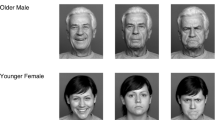

We investigated whether the well-documented babyface stereotype is moderated by facial movement or expression. Impressions of more babyfaced women as warmer and less dominant were weaker when faces were moving than when they were static. These moderating effects of facial movement were consistent with its tendency to reduce the perceived anger of low babyfaced women. Impressions of more babyfaced women as less dominant were equally strong whether faces showed a neutral or surprised expression, but impressions of them as warmer were significant only for neutral expressions. The moderating effect of facial expression on impressions of warmth was consistent with the tendency for surprise expressions to attenuate differences in the perceived babyfaceness of high and low babyfaced people. Theoretical interpretations and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Several ratings were missing due to technical errors. In the static neutral condition; 10 subjects’ anger ratings were missing for one face, 17 anger ratings were missing for another face, 17 sad ratings were missing for two faces, 10 happiness ratings were missing for two faces, and 10 surprise ratings were missing for one face. In the static surprise condition; 7 sociable ratings were missing for one face and 7 of each rating (angry, attractive, babyfaceness, dominance, fear, happiness, shrewd, sad, sociable, strong, surprise, trustworthy, and warm) were missing for another face. In addition, static (both neutral and surprise) trustworthy ratings were dropped from three raters in Blocks 1 and 4, and static (neutral and surprise) sociable ratings were dropped from two raters in Block 4 to increase reliability.

Fear was not controlled because it is structurally similar to surprise, and a factor analysis on emotion ratings revealed that surprise and fear loaded on one factor while sadness, anger, and happiness (reversed) loaded on a second factor. Anger was not controlled because it was entered at Step 2 to determine whether it attenuated the moderation of structural babyface effects by movement and expression.

Consistent with the manipulation check analysis, a Movement × Expression effect for anger impressions, β = 0.34, p = 0.01, revealed that surprised faces were judged more angry than neutral ones in the moving face condition, and less angry in the static face condition, although neither of the simple effects was significant, β = 0.23, p < 0.15, for moving faces and β = −0.16, p > 0.25 for static faces. We also performed regression analyses on the other emotion ratings which showed the following effects. Consistent with the manipulation check analysis, faces were perceived as more fearful if they were higher in babyfaceness, β = 0.36, p < 0.01, and if they were surprised, β = 0.44, p < 0.001, or moving, β = 0.24, p < 0.05. Faces were perceived as sadder if they were higher in babyfaceness, β = 0.35, p = 0.01, with a significant Structural Babyface × Movement interaction, β = −0.28, t = 2.50, p < 0.02, reflecting a significant effect of babyfaceness in the static face condition, β = 0.35, p < 0.05, but not in the dynamic face condition, β = −0.05, p > 0.50. Ratings of happiness revealed no significant effect of babyfaceness and no interactions of babyfaceness with expression or movement, all p > 0.30.

An unpredicted Movement × Expression effect for warmth impressions, β = −0.27, p < 0.01, revealed that surprised faces were judged less warm than neutral faces in the moving face condition, β = −0.32, p < 0.001, but not in the static face condition, β = −0.01, p > 0.50.

References

Becker, D. V., Kenrick, D. T., Neuberg, S. L., Blackwell, K. C., & Smith, D. M. (2007). The confounded nature of angry men and happy women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 179–190.

Collins, M., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (1995). The contributions of appearance to occupational outcomes in civilian and military settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 129–163.

Enlow, D. H. (1990). Facial growth (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Harcourt Brace.

Hemmesch, A., Tickle-Degnan, L., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (2009). The influence of facial masking and sex on older adults’ impressions of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Psychology and Aging, 24, 542–549.

Hess, U., Adams, R. B., Grammer, K., & Kleck, R. E. (2009). Face gender and emotion expression: Are angry women more like men? Journal of Vision, 9(12), 19.

Hess, U., Adams, R. B., & Kleck, R. E. (2004). Facial appearance, gender, and emotion expression. Emotion, 4(4), 378–388.

Knutson, B. (1996). Facial expressions of emotion influence interpersonal trait inferences. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 20(3), 165–182.

Lyons, K. D., Tickle-Degnen, L., Henry, A., & Cohn, E. (2004). Impressions of personality in Parkinson’s disease: Can rehabilitations practitioners see beyond the symptoms? Rehabilitation Psychology, 49, 328–333.

Marsh, A. A., Adams, R. B., Jr., & Kleck, R. E. (2005). Why do fear and anger look the way they do? Form and social function in facial expressions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 73–86.

Montepare, J. M., & Dobish, H. (2003). The contribution of emotion perceptions and their overgeneralizations to trait impressions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 27(4), 237–254.

Montepare, J. M., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (1998). Person perception comes of age: The salience and significance of age in social judgments. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 93–163). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

O’Toole, A. J., Harms, J., Snow, S. L., Hurst, D. R., Pappas, M. R., Ayyad, J. H., et al. (2005). A video database of moving faces and people. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 27(5), 812–816.

Sacco, D. F., & Hugenberg, K. (2009). The look of fear and anger: Facial maturity modulates recognition of fearful and angry expressions. Emotion, 9(1), 39–49.

Zebrowitz, L. A. (1997). Reading faces: Window to the soul? Boulder. CO: Westview Press.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Andreoletti, C., Collins, M. A., Lee, S. Y., & Blumenthal, J. (1998). Bright, bad, babyfaced boys: Appearance stereotypes do not always yield self-fulfilling prophecy effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1300–1320.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Bronstad, M. P., & Montepare, J. M. (2011). An ecological theory of face perception. In N. Ambady, R. Adams, K. Nakayama, & S. Shimojo (Eds.), The science of social vision (pp. 3–30). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Kikuchi, M., & Fellous, J.-M. (2007). Are effects of emotion expression on trait impressions mediated by babyfaceness? Evidence from connectionist modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 648–662.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Kikuchi, M., & Fellous, J. M. (2010). Facial resemblance to emotions: Group differences, impression effects, and race stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 175–189.

Zebrowitz, L. A., & Lee, S. Y. (1999). Appearance, stereotype incongruent behavior, and social relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 569–584.

Zebrowitz, L. A., & McDonald, S. (1991). The impact of litigants’ babyfacedness and attractiveness on adjudications in small claims courts. Law and Human Behavior, 15, 603–623.

Zebrowitz, L. A., & Montepare, J. M. (2008). Social psychological face perception: Why appearance matters. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1497–1517.

Zebrowitz-McArthur, L., & Montepare, J. M. (1989). Contributions of a babyface and a childlike voice to impressions of moving and talking faces. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 13(3), 189–203.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [grant numbers MH066836 and K02MH72603].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sparko, A.L., Zebrowitz, L.A. Moderating Effects of Facial Expression and Movement on the Babyface Stereotype. J Nonverbal Behav 35, 243–257 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-011-0111-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-011-0111-8