Abstract

This paper examines the determinants of happiness inequality in Japan using unique data from the “Preference Parameters Study” of Osaka University, a nationally representative survey conducted in Japan. By estimating Recentered Influence Function regressions, we find that household income has a negative and significant effect on happiness inequality, as found for other advanced economies, though people’s perception of their relative standing in the income spectrum also matters for the dispersion of happiness. Moreover, the regression results show that the insecurity faced by people about their jobs and life after retirement is also significantly associated with the widening of happiness inequality. Such findings are cause for grave concern given that the share of irregular jobs, which tend to be low paid and insecure, in total employment significantly increased in Japan during the Lost Two Decades and that this increasing trend has not yet been reversed.

Source: Happiness inequality: Calculations based on the 2003–2013 Preference Parameters Study data. Real GDP per capita: Calculations based on data on real GDP from the National Accounts of Japan (Cabinet Office, http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/menu.html, accessed on April 14, 2015) and data on population from the Population Estimates (Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2.htm, accessed on April 14, 2015)

Source: Calculations based on the 2013 Preference Parameters Study data

Source: The Labor Force Survey (Historical data: Tables 9 and 10), Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (http://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/longtime/03roudou.htm, accessed on May 14, 2015)

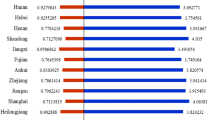

Source: Calculations based on the 2013 Preference Parameters Study data

Source: Calculations based on the 2013 Preference Parameters Study data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For instance, under the initiative of the former French President Sarkozy, the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress was created in 2008 to identify the limitations of GDP as an indicator of economic performance and social progress and to propose alternative measures. In the case of the United Kingdom, the Measuring National Well-being Programme was launched in 2010 to construct measures of the nation’s well-being beyond GDP. A set of objective and subjective indicators has been selected and national well-being has been monitored through these indicators since then. As for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), it launched the Better Life Index Initiative in 2011, which has developed statistics to capture aspects of life that matter to people in terms of material living conditions and that shape the quality of people’s lives.

As noted by Diener et al. (2002), subjective well-being can be defined as an individual’s affective and cognitive evaluations of his/her life, which include emotional reactions to events (both positive and negative affect) as well as cognitive judgements of life satisfaction. As such, subjective well-being can be considered as “a general area of scientific interest rather than a single specific construct” (Diener et al. 1999, p. 277).

According to the Helliwell et al. (2015), Japan’s rank of happiness (for the period 2012–2014) was 25th among the 34 OECD member countries.

Japan’s average annual unemployment rate was about 4.2% between 2000 and 2015 according to data from the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (http://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/longtime/03roudou.htm#hyo_1, accessed on March 1, 2016).

Irregular employees include those who are working as a part-time worker, temporary worker, fixed-term worker, or dispatched worker from a temporary agency.

While employees in the private sector participate in the Employees’ Pension Plan, government employees participate in the Mutual Aid Pension Plan instead.

On average, only about 52% of irregular employees were found to have participated in the Employees’ Pension Plan in 2014 according to data from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/itiran/roudou/koyou/keitai/14/index.html, accessed on March 7, 2016).

The data used for their analysis come from the World Values Surveys, the German Socio-Economic Panel, the British Household Panel Survey, the American General Social Survey, and the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (Clark et al. 2014). While Becchetti et al. (2014) note a rise in happiness inequality in Germany between 1992 and 2007, Clark et al. (2014) look at a longer period and obtain a different picture, namely that happiness inequality fell sharply in the 1980s and then fluctuated around a flat trend in the 1990s.

Note that this paper focuses on examining the determinants of the level of, rather than trends over time in, happiness inequality using data from the 2013 wave because this wave contains some useful variables that are not available in earlier waves. Since the number of studies that examine the determinants of happiness inequality remains limited, analyzing the determinants of the level of happiness inequality itself provides useful findings. The regressions were also estimated using pooled data from the 2012 and 2013 waves (the time period was too short to conduct a panel data analysis). The estimation results were very close to those presented in this paper, which were obtained from regressions estimated using only data from the 2013 wave.

These criteria include: (1) single finite number as result, (2) interval level of measurement, (3) independence of scale range, (4) independence of sample size, (5) independence of the mean, (6) equal values for equally unequal distributions, (7) differentiation between more and less unequal distributions, and (8) sensitive to degree of inequality (Kalmijn and Veenhoven 2005).

Kalmijn and Veenhoven (2005) computed happiness inequality for various countries using those four acceptable inequality metrics and find that those four statistics generate similar results in terms of the ranking of countries based on happiness inequality. These results therefore lead them to conclude that no advance in understanding is to be expected from switching from using the standard deviation to some other inequality statistic (Kalmijn and Veenhoven 2005, p. 389).

It should also be noted that, in the case of Japan, there is a relatively large number of people who participate only in the National Pension Plan and receive only the basic pension, which is not related to their income levels, as noted earlier.

As part of the Comprehensive Reform of Social Security and Tax, the relevant law was enacted to expand the application of the Employees’ Pension to part-time workers in 2012, which became effective in October 2016.

References

Becchetti, L., Massari, R., & Naticchioni, P. (2014). The drivers of happiness inequality: Suggestions for promoting social cohesion. Oxford Economic Papers, 66(2), 419–442.

Beegle, K., Himelein, K., & Ravallion, M. (2012). Frame-of-reference bias in subjective welfare. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81(2), 556–570.

Clark, A. E., Flèche, S., & Senik, C. (2014). The Great happiness moderation: Well-being inequality during episodes of income growth. In A. E. Clark & C. Senik (Eds.), Happiness and economic growth: Lessons from developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 96–144.

Clark, A. E., Flèche, S., & Senik, C. (2016). Economic growth evens out happiness: Evidence from six surveys. Review of Income and Wealth, 62(3), 405–419.

Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2006). Some uses of happiness data in economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 25–46.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1991). Explaining sex differences in social behavior: A meta-analytic perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(3), 306–315.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramowitz. New York: Academic Press.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Firpo, S., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2007). Decomposing wage distributions using recentered influence function regressions, unpublished manuscript, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro and University of British Columbia.

Firpo, S., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2009). Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica, 77(3), 953–973.

Fleurbaey, M. (2009). Beyond GDP: The quest for a measure of social welfare. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(4), 1029–1075.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. Economic Journal, 110(466), 918–938.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists lean from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 402–435.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (Eds.). (2015). World happiness report 2015. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Kalmijn, W., & Veenhoven, R. (2005). Measuring inequality of happiness in nations. In search for proper statistics. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(4), 357–396.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. London: Penguin Books.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). OECD economic surveys Japan. Paris: OECD.

Ott, J. (2005). Level and inequality of happiness in nations: Does greater happiness of a greater number imply greater inequality in happiness? Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(4), 397–420.

Ovaska, T., & Takashima, R. (2010). Does a rising tide life all the boats? Explaining the national inequality of happiness. Journal of Economic Issues, 44(1), 205–223.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Happiness inequality in the United States. Journal of Legal Studies, 37(S2), S33–S79.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/en/index.htm. Accessed on 27 Jan 2015.

Tsutsui, Y., Ohtake, F., & Ikeda, S. (2009). Naze Anataha Fukounanoka? (in Japanese) (why are you unhappy?). Osaka Daigaku Keizaigaku (Osaka Economic Papers), 58(4), 20–57.

Van Praag, B. M. S. (1991). Ordinal and cardinal utility: An integration of the two dimensions of the welfare concept. Journal of Econometrics, 50(1–2), 69–89.

Van Praag, B. M. S. (2011). Well-being inequality and reference groups: An agenda for new research. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(1), 111–127.

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Return of inequality in modern society? Test by dispersion of life-satisfaction across time and nations. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(4), 457–487.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The empirical work undertaken in this paper utilizes micro data from the Preference Parameters Study of Osaka University’s 21st Century COE Program ‘Behavioral Macrodynamics Based on Surveys and Experiments’ and its Global COE Project ‘Human Behavior and Socioeconomic Dynamics.’ I acknowledge the program/project’s contributors—Yoshiro Tsutsui, Fumio Ohtake and Shinsuke Ikeda. I am also grateful to Charles Yuji Horioka and participants of the SASE (Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics) 27th Annual Conference, Singapore Economic Review Conference 2015, and the 2015 IAREP (International Association for Research in Economic Psychology)–SABE (Society for the Advancement of Behavioral Economics) Joint Conference for their invaluable comments. This work was supported by JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) KAKENHI Grant Number 15H01950, a project research grant from the Asian Growth Research Institute, and a grant from the MEXT Joint Usage/Research Center at the Institute of Social and Economic Research, Osaka University.

Appendix

Appendix

Description of variables

Variables | Description |

|---|---|

Age | Age expressed in years |

Age squared | Age squared |

Female | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents are female |

Marital Status | |

Never married | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have never been married |

Married | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have spouses or partners who are living with them |

No longer married | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents are divorced, widowed or separated |

Education | |

Junior high school | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have completed junior high school education or lower |

High school | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have completed high school education |

Junior college | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have completed junior college education |

University | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have obtained a university degree or higher |

Poor health | Dummy variable for visiting a doctor on a regular basis because of a chronic disease or injury |

Child | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have a child/children |

Household size | Total number of household members |

Household income | Since the choices of the answers to the question on annual household income were in brackets, we created a continuous variable by assigning the following values to each answer: (1) Less than 1 million yen: 800,000 yen (2) 1 million to less than 2 million yen: 1.5 million yen (3) 2 million to less than 4 million yen: 3 million yen (4) 4 million to less than 6 million yen: 5 million yen (5) 6 million to less than 8 million yen: 7 million yen (6) 8 million to less than 10 million yen: 9 million yen (7) 10 million to less than 12 million yen: 11 million yen (8) 12 million to less than 14 million yen: 13 million yen (9) 14 million to less than 16 million yen: 15 million yen (10) 16 million to less than 18 million yen: 17 million yen (11) 18 million to less than 20 million yen: 19 million yen (20) 20 million yen or over: 25 million yen We have then divided the figure (in 10,000 yen) by the number of household members and taken its natural logarithm. |

Homeownership | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents own a house or an apartment |

Has loans | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have loans |

Employment | |

Regular job | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have a regular job |

Irregular job | Dummy variable equals one if respondents have an irregular job (i.e., working as a part-time worker, temporary worker, fixed-term worker, or dispatched worker from a temporary agency) |

Unemployed | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents are unemployed |

Not in labor force | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents are not in the labor force (i.e., housewives/husbands, students or retired) |

Likely unemployed | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents are currently employed but perceive a high risk of being unemployed in the next 2 years |

Public pensions | (1) Between 0 and 9%: 5% (2) Between 10 and 19%: 15% (3) Between 20 and 29%: 25% (4) Between 30 and 39%: 35% (5) Between 40 and 49%: 45% (6) Between 50 and 59%: 55% (7) Between 60 and 60%: 65% (8) Between 70 and 79%: 75% (9) Between 80 and 80%: 85% (10) 90% or over: 95% |

Altruistic | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents have donated any money in the previous year |

Risk lover | Chance of rain (%) that will make respondents bring an umbrella with them when they go out |

Low time preference | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents used to get homework done right away or fairly early during school vacations when they were a child |

Relatively poor | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents think that the living standard of others is much higher or somewhat higher than their own |

Relatively rich | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents think that the living standard of others is much lower or somewhat lower than their own |

Regions | |

Hokkaido | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Hokkaido |

Tohoku | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Tohoku |

Kanto | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Kanto |

Koshinetsu | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Koshinetsu |

Hokuriku | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Hokuriku |

Tokai | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Tokai |

Kinki | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Kinki |

Chugoku | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Chugoku |

Shikoku | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Shikoku |

Kyushu | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in Kyushu |

Major city | Dummy variable that equals one if respondents reside in a major (ordinance-designated) city |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niimi, Y. What Affects Happiness Inequality? Evidence from Japan. J Happiness Stud 19, 521–543 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9835-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9835-9