Abstract

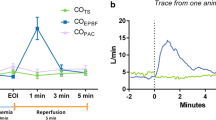

The aim of this study was to test the effect of cardiac output (CO) and pulmonary artery hypertension (PHT) on volumetric capnography (VCap) derived-variables. Nine pigs were mechanically ventilated using fixed ventilatory settings. Two steps of PHT were induced by IV infusion of a thromboxane analogue: PHT25 [mean pulmonary arterial pressure (MPAP) of 25 mmHg] and PHT40 (MPAP of 40 mmHg). CO was increased by 50 % from baseline (COup) with an infusion of dobutamine ≥5 μg kg−1 min−1 and decreased by 40 % from baseline (COdown) infusing sodium nitroglycerine ≥30 μg kg−1 min−1 plus esmolol 500 μg kg−1 min−1. Another state of PHT and COdown was induced by severe hypoxemia (FiO2 0.07). Invasive hemodynamic data and VCap were recorded and compared before and after each step using a mixed random effects model. Compared to baseline, the normalized slope of phase III (SnIII) increased by 32 % in PHT25 and by 22 % in PHT40. SnIII decreased non-significantly by 4 % with COdown. A combination of PHT and COdown associated with severe hypoxemia increased SnIII by 28 % compared to baseline. The elimination of CO2 per breath decreased by 7 % in PHT40 and by 12 % in COdown but increased only slightly with COup. Dead space variables did not change significantly along the protocol. At constant ventilation and body metabolism, pulmonary artery hypertension and decreases in CO had the biggest effects on the SnIII of the volumetric capnogram and on the elimination of CO2.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aitken RS, Clark-Kennedy AE. On the fluctuation in the composition of the alveolar air during the respiratory cycle in muscular exercise. J Physiol. 1928;65:389–411.

Fletcher R, Jonson B, Cumming G, Brew J. The concept of deadspace with special reference to the single breath test for carbon dioxide. Br J Anaesth. 1981;53:77–88.

Breen PH, Isserles SA, Harrison BA, Roizen MF. Simple computer measurement of pulmonary VCO2 per breath. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:2029–35.

Breen PH, Mazumdar B, Skinner SC. Comparison of end-tidal PCO2 and average alveolar expired PCO2 during positive end-expiratory pressure. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:368–73.

Fletcher R, Jonson B. Deadspace and the single breath test for carbon dioxide during anaesthesia and artificial ventilation. Effects of tidal volume and frequency of respiration. Br J Anaesth. 1984;56:109–19.

Maisch S, Reissmann H, Fuellekrug B, Weismann D, Rutkowski T, Tusman G, Bohm SH. Compliance and dead space fraction indicate an optimal level of positive end-expiratory pressure after recruitment in anesthetized patients. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:175–81. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000287684.74505.49.

Taskar V, John J, Larsson A, Wetterberg T, Jonson B. Dynamics of carbon dioxide elimination following ventilator resetting. Chest. 1995;108:196–202.

Kallet RH, Daniel BM, Garcia O, Matthay MA. Accuracy of physiologic dead space measurements in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome using volumetric capnography: comparison with the metabolic monitor method. Respir Care. 2005;50:462–7.

Tusman G, Areta M, Climente C, Plit R, Suarez-Sipmann F, Rodriguez-Nieto MJ, Peces-Barba G, Turchetto E, Bohm SH. Effect of pulmonary perfusion on the slopes of single-breath test of CO2. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:650–5.

Burki NK. The dead space to tidal volume ratio in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:679–85.

Tusman G, Bohm SH, Suarez-Sipmann F, Turchetto E. Alveolar recruitment improves ventilatory efficiency of the lungs during anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:723–7. doi:10.1007/BF03018433.

Bohm SH, Maisch S, von Sandersleben A, Thamm O, Passoni I, Martinez Arca J, Tusman G. The effects of lung recruitment on the Phase III slope of volumetric capnography in morbidly obese patients. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:151–9. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e31819bcbb5.

Mosing M, Iff I, Hirt R, Moens Y, Tusman G. Evaluation of variables to describe the shape of volumetric capnography curves during bronchoconstriction in dogs. Res Vet Sci. 2012;93:386–92. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.05.014.

Crawford AB, Makowska M, Paiva M, Engel LA. Convection- and diffusion-dependent ventilation maldistribution in normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59:838–46.

Horsfield K, Cumming G. Functional consequences of airway morphology. J Appl Physiol. 1968;24:384–90.

Verbanck S, Paiva M. Model simulations of gas mixing and ventilation distribution in the human lung. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:2269–79.

Tusman G, Suarez-Sipmann F, Bohm SH, Borges JB, Hedenstierna G. Capnography reflects ventilation/perfusion distribution in a model of acute lung injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:597–606. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02404.x.

Tusman G, Scandurra A, Bohm SH, Suarez-Sipmann F, Clara F. Model fitting of volumetric capnograms improves calculations of airway dead space and slope of phase III. J Clin Monit Comput. 2009;23:197–206. doi:10.1007/s10877-009-9182-z.

Bohr C. Über die Lungenathmung. Centralblatt für Physiologie. 1887;1(14):236–68.

Enghoff H. Volumen inefficax. Bemerkungen zur Frage des schädlichen Raumes. Uppsala Lak Forhandl. 1938;44:191–218.

Tusman G, Sipmann FS, Bohm SH. Rationale of dead space measurement by volumetric capnography. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:866–74. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e318247f6cc.

Berggren SM. The oxygen deficit of arterial blood caused by non-ventilated parts of the lung. Acta Physiol Scand. 1942;4:4–9.

Stromberg NO, Gustafsson PM. Ventilation inhomogeneity assessed by nitrogen washout and ventilation-perfusion mismatch by capnography in stable and induced airway obstruction. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29:94–102. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(200002)29:2<94.

Downie SR, Salome CM, Verbanck S, Thompson B, Berend N, King GG. Ventilation heterogeneity is a major determinant of airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma, independent of airway inflammation. Thorax. 2007;62:684–9. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.069682.

Tusman G, Gogniat E, Bohm SH, Scandurra A, Suarez-Sipmann F, Torroba A, Casella F, Giannasi S, Roman ES. Reference values for volumetric capnography-derived non-invasive parameters in healthy individuals. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27:281–8. doi:10.1007/s10877-013-9433-x.

Verschuren F, Liistro G, Coffeng R, Thys F, Roeseler J, Zech F, Reynaert M. Volumetric capnography as a screening test for pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Chest. 2004;125:841–50.

Kline JA, Israel EG, Michelson EA, O’Neil BJ, Plewa MC, Portelli DC. Diagnostic accuracy of a bedside D-dimer assay and alveolar dead-space measurement for rapid exclusion of pulmonary embolism: a multicenter study. JAMA. 2001;285:761–8.

Glenny RW, Robertson HT. Fractal properties of pulmonary blood flow: characterization of spatial heterogeneity. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:532–45.

Glenny RW, Lamm WJ, Albert RK, Robertson HT. Gravity is a minor determinant of pulmonary blood flow distribution. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:620–9.

Hakim TS, Lisbona R, Dean GW. Gravity-independent inequality in pulmonary blood flow in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:1114–21.

Hakim TS, Lisbona R, Dean GW. Effect of cardiac output on gravity-dependent and nondependent inequality in pulmonary blood flow. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1570–8.

Presson RG Jr, Baumgartner WA Jr, Peterson AJ, Glenny RW, Wagner WW Jr. Pulmonary capillaries are recruited during pulsatile flow. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1183–90. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00845.2001.

Wagner WW Jr, Latham LP. Pulmonary capillary recruitment during airway hypoxia in the dog. J Appl Physiol. 1975;39:900–5.

Tusman G, Bohm SH, Suarez-Sipmann F, Scandurra A, Hedenstierna G. Lung recruitment and positive end-expiratory pressure have different effects on CO2 elimination in healthy and sick lungs. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:968–77. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181f0c2da.

Fletcher R. Deadspace, invasive and non-invasive. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57:245–9.

Tusman G, Suarez-Sipmann F, Paez G, Alvarez J, Bohm SH. States of low pulmonary blood flow can be detected non-invasively at the bedside measuring alveolar dead space. J Clin Monit Comput. 2012;26:183–90. doi:10.1007/s10877-012-9358-9.

Putensen C, Rasanen J, Downs JB. Effect of endogenous and inhaled nitric oxide on the ventilation-perfusion relationships in oleic-acid lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:330–6. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049811.

Skimming JW, Banner MJ, Spalding HK, Jaeger MJ, Burchfield DJ, Davenport PW. Nitric oxide inhalation increases alveolar gas exchange by decreasing deadspace volume. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1195–200.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Axon Lab (Instrumentation Laboratory, Axon Lab, Switzerland) and funded by a grant from the Forschungskredit of the University of Zürich, awarded to M. Mosing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Cantonal Veterinary Office of Zürich (176/2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mosing, M., Kutter, A.P.N., Iff, S. et al. The effects of cardiac output and pulmonary arterial hypertension on volumetric capnography derived-variables during normoxia and hypoxia. J Clin Monit Comput 29, 187–196 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-014-9588-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-014-9588-0