Abstract

In this work, the effect of varying the size of the precursor raw materials SiO2 and ZrO2 in the solid-state synthesis of NASICON in the form Na3Zr2Si2PO12 was studied. Nanoscale and macro-scale precursor materials were selected for comparison purposes, and a range of sintering times were examined (10, 24 and 40 h) at a temperature of 1230 °C. Na3Zr2Si2PO12 pellets produced from nanopowder precursors were found to produce substantially higher ionic conductivities, with improved morphology and higher density than those produced from larger micron-scaled precursors. The nanoparticle precursors were shown to give a maximum ionic conductivity of 1.16 × 10−3 S cm−1 when sintered at 1230 °C for 40 h, in the higher range of published solid-state Na3Zr2Si2PO12 conductivities. The macro-precursors gave lower ionic conductivity of 0.62 × 10−3 S cm−1 under the same processing conditions. Most current authors do not quote or consider the precursor particle size for solid-state synthesis of Na3Zr2Si2PO12. This study shows the importance of precursor powder particle size in the microstructure and performance of Na3Zr2Si2PO12 during solid-state synthesis and offers a route to improved predictability and consistency of the manufacturing process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The discovery of fast ionic conduction of sodium ions in β-alumina led to the interest of research in solid electrolytes for fast ionic transport of sodium ions [1]. Early studies by Goodenough et al. [2] included the development of Na1+XZr2SixP3−xO12 (0 < x < 3), sodium (Na) superionic (Si) conductor (CON) (NASICON)-based material structures. NASICON has gained attention due to its relatively high conductivity (10–3 S cm–1) at room temperature [3] which makes it a candidate material particularly for solid-state sodium-ion batteries but also sensors [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Stationary sodium-ion batteries are the most obvious market for NASICON and can potentially exploit the global abundance of sodium when compared with lithium. Such batteries have been most effectively demonstrated at high temperatures [11], but this presents problems in terms of safety, operating simplicity and cost. The ideal solution for widespread adoption is to ultimately use room temperature conductive solid electrolytes. In addition to solid ceramic electrolytes, NASICON can be incorporated into polymer–ceramic composites to give high ionic conductivity together with enhanced mechanical properties and low interfacial resistance [12].

The NASICON structure consists of a skeletal array of atoms which are stabilised by electrons, donated by alkali ions partially occupying sites in a three-dimensionally linked interstitial space [1]. The NASICON structure is said to be rhombohedral (R3c), except in the intervals 1.8 < x < 2.2 [8, 10]. In this interval, a small distortion to the monoclinic symmetry (C2/c) takes place changing the microstructure [10]. In the rhombohedral configuration, the Na+ ions can occupy two different sites within the structure when x > 0. In a monoclinic structure, Na+ can occupy three sites, increasing its ion conduction pathways [13]. Na3Zr2Si2PO12 is the most common formulation of NASICON and is found to have ionic conductivity in the higher range when compared with other types [14]. This is often known as Hong-type NASICON and was pioneered by the early work by Hong and Goodenough [2, 15], and the reported conductivity via the most common conventional solid-state sintered method ranges from 9.2 × 10−5 to 1.2 × 10−3 S cm−1 [16] with variance due to different densities and microstructures due to the different processing conditions. The solid-state method is the most common method described in the literature and offers a simpler and less expensive method compared to the alternatives. It typically consists of several stages including mixing/milling of powdered precursors, calcination and a final sintering stage [11, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The usual laboratory method of sintering is to compress the pre-sintered powder into a pellet and sinter in a box furnace. Table 1 provides a selection of room temperature conductivities found in the literature for NASICON produced by solid-state routes.

In addition to conventional solid-state reaction, there are a number of synthesis methods to form Na3Zr2Si2PO12. The sol–gel route is much more complex, and harder to optimise, but requires lower sinter temperatures than the solid-state route [10, 24,25,26,27,28,29], the key benefit being production of a purer phase. The high temperatures in solid-state processing are associated with thermal decomposition and ZrO2 contamination, with segregation of zirconia at the grain boundary resulting in a reduction in ionic conductivity [23]. Di Vona et al. [28] report a non-hydrolytic sol–gel route as an easier to control method. As an alternative to conventional sintering, spark plasma sintering methods have attained a conductivity of 1.8 × 10−3 S cm−1 [23], although this is a very energy intensive process [3]. Benefits in conductivity can also be obtained doping with other materials such as Germanium, Yttria or Scandium [30,31,32].

The microstructure of solid-state-reacted NASICON has been reported to have a major impact on the electrical performance [22]. A major contributor to variation in the microstructure is the sintering conditions [20, 22, 23]. Lee et al. [20] found that ionic conductivity increased with sintering duration due to an increase in grain growth and densification [20], while Fuentes et al. [19] found that increases in sintering time increased conductivity to a certain point (40 h) after which further sintering duration (80 h) was seen to increase grain boundary resistance and hinder electrical performance due to the presence of a liquid phase along the grain boundaries. Additionally, excessive temperature further increases the inherent risk of formation of secondary unwanted material phases, mainly monoclinic ZrO2, which increase with temperature [21]. An appropriate sintering temperature and duration are therefore crucial to achieve a large homogeneous grain size distribution and increased densification, but also to maintain the conductivity by inhibiting impure phases.

Each synthesis method and its associated processing conditions will yield different pre-sintering powder properties such as particle size distribution, morphology and composition [16]. Lee et al. [20] looked at the effect of different pre-sintered particle sizes by comparing ball milling and jet milling methods after calcination. They reported an increase in conductivity by over 20 times for NASICON by reducing particle size of intermediates via jet milling after the final high-temperature calcination stage and attribute this improvement to a larger surface free energy and surface area providing a higher driving force during sintering and higher densification of the fine powder, although conductivities were low compared with other references (Table 1). Porkodi et al. [29] reported the advantage of using a molecular precursor, sol–gel-based approach to NASICON synthesis. This approach produced nanoparticle precursors which may be responsible for the increased NASICON phase purity, densification and higher ionic conductivity of the resultant material. The smaller particle size can increase the reactivity of the powders, improving the reaction kinetics. Densification is driven by the reduction in surface free energy through the reduction in surface area, and reactivity is inherently higher when using very small particle precursors [33].

Particle size is a key determinant of performance, yet in the current literature, no study seems to exist investigating the effect on conductivity from using different precursor particle sizes via the solid-state synthesis method. Much of the current literature does not even refer to the particle size of the raw precursors, which is a material characteristic which could be fundamentally important for the optimisation of NASICON. Furthermore, the use of smaller, and potentially more reactive, precursors could reduce the processing requirements. Choi and Park [21] reported that finer precursor powders produced higher densities, and reacted at lower temperatures, but the reaction did not proceed to completion when coarse powders were used. However, impedance measurements were not taken and different precursors were used for the finest powders (ZrSiO4 instead of SiO2 and ZrO2). In addition to this, the smallest particles were only down to 0.5 microns and could not benefit thermodynamically in the same way as nanoparticles. Intensive ball milling procedures [20] or complex chemical synthesis methods are often used to achieve smaller more reactive particles during the pre-sintering phase, but the use of smaller particles as precursors could potentially reduce the processing requirements for pre-sintering powders, while also offering a more standardised and predictable morphology than milling procedures would offer. Nanoparticle precursor materials are readily available raw materials and are potentially an attractive approach for scalable conventional solid-state synthesis and improvement in the resultant material by changing the particle size of the raw material precursors rather than processing intermediates. This could negate the need for complicated/expensive chemically sensitive methods or extensive processing methods to create desirable powder characteristics.

In this study, the potential advantages of using nanoscale precursor particles for the synthesis of Na3Zr2Si2PO12 NASICON by solid-state reaction were investigated by direct comparison with macro-scale precursors, with all other processing parameters fixed. Of major interest was how this affected the microstructure, crystalline structure and impurities, and crucially the electrical performance. Firstly, the effect that precursor size had on the powder properties prior to the final sintering stage was analysed in terms of particle size distribution and microstructure. NASICON pellets were then prepared from these powders, at a range of sintering durations (10, 24 and 40 h) with microstructure, crystalline structure, density and finally electrical performance analyses performed.

Experimental

Precursor materials

To investigate the effect of changing the precursor particle size, two particle size ranges of precursors were selected for zirconium (IV) oxide (ZrO2) and silicon dioxide (SiO2) as detailed in Table 2. The same tri-sodium phosphate dodecahydrate (Na3PO4·12H2O) was used in both nano- and macro-formulations as this decomposes at relatively low temperatures. All precursors were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich UK with particle sizing information obtained from the product data sheets where available. Macro-silicon dioxide was measured using a laser diffraction particle size analyser (Mastersizer 2000, Malvern Panalytical). Product numbers are also provided in the table.

Preparation of solid Na3Zr2Si2PO12 electrolyte

The Na3Zr2Si2PO12 was synthesised using a solid-state reaction with a series of processing steps as outlined in Fig. 1, with both precursor types subjected to the same processing conditions and durations. The precursors SiO2, ZrO2 and Na3PO4·12H2O were mixed in stoichiometric quantities then wet milled together in isopropanol using a planetary ball mill (Fritsch Pulverisette 5/2) at 120 RPM for 2 h. The mixture was then dried at 80 °C for 12 h; then, pellets were formed by cold uniaxial pressing in a 16-mm-diameter die at 250 MPa. A calcination step was then carried out in a box furnace at 400 °C for 5 h. The pellets were then handground into a fine powder and then pelletised again. A further calcination step was then carried out at 1100 °C for 12 h. A further wet milling using isopropanol was then carried out at 120 RPM for 3 h. The resulting powder was then dried (with powder samples taken for pre-sinter analysis) and pelletised, with a final crystallisation sintering step carried out 1230 °C. Sintering times of 10, 24 and 40 h were used to investigate the combined effects of sintering duration and precursor particle size on the Na3Zr2Si2PO12. The sintered pellets were then polished down to 1.5 mm thickness using silicon carbide paper.

Characterisation of Na3Zr2Si2PO12

Morphological measurements were taken of both powders prior to the final sintering stage and the post-sintered pellets. For the pre-sintered powders, morphology was assessed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Zeiss EVO 10), particle size measurements were taken using a laser diffraction particle size analyser (Mastersizer 2000, Malvern Panalytical), and finally, surface area analysis was conducted using BET (Quantachrome NOVA 2200e, Quantachrome Instruments using N2 sorption). The crystalline structure of the post-sintered pellets was characterised using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (D8 Advance, Bruker AXS GmbH) in the 10o–70o 2θ range with a copper source. Pellets were also analysed using SEM, and density measurements were taken using the Archimedes technique (Attension Sigma 700, Biolin Scientific). Finally, the ionic conductivity was evaluated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) (VMP3, Bio-Logic Science Instruments Ltd). For EIS, the electrolyte pellets (~ 14.5 mm diameter 1.5 mm thickness) were sputtered with platinum to create blocking electrodes and then clamped between stainless steel discs to ensure good surface contact and electrical conductivity. A frequency sweep of 100 MHz to 1 MHz was used at a voltage amplitude of 100 mV.

Results

Analysis of pre-sintered powders

Microstructure images of the powder samples prior to final sintering (and after ball milling) are shown in Fig. 2 for both nano- and macro-precursors. The powders derived from both precursors showed particles of around 1 μm and larger and a tendency for particles to be agglomerated rather than existing as fine powder. Powders produced from the macro-powders appeared slightly larger with a greater tendency for clumping around agglomerates. The particle size distribution of the pre-sintered powders, obtained via laser diffraction, is shown in Fig. 3. Both samples showed a bimodal particle size distribution with similar peak distributions around ~ 5 μm and ~ 90 μm in size. The nanoprecursors gave powders with a greater number of the smaller particle sizes in the 0.3–2 μm range and a lower number of the largest particles. Other studies which used longer duration and higher intensity milling [3, 20] yielded monomodal distributions and significantly smaller particle sizes. This suggests that the milling procedure in this study was not particularly aggressive in breaking down agglomerates, but slightly, but not substantially, smaller particles were achieved via nanoprecursors.

The pre-sintered powders produced from nanoprecursors gave a Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area of 6.732 m2/g, while those from macro-precursors gave a substantially lower surface area of 0.819 m2/g. This is indicative of a much more porous structure in the pre-sintered powders produced from nanoprecursors. Compared with the literature, the macro-precursor powder surface area was lower than that reported by Naqash et al. [3] for a solid-state process. This might be due to the relatively low intensity of the ball milling process in this case. However, the surface area for the nanoprecursor powder was higher than that reported (3.935 m2/g) and was of a similar magnitude for pre-sintered powders based on a sol–gel route (7.64 m2/g) by the same authors [3].

Analysis of finished Na3Zr2Si2PO12 pellets

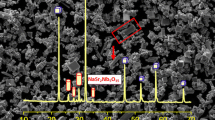

X-ray diffraction patterns of the finished pellets obtained from powders of both macro- and nanoprecursors are compared at a range of treatment times in Fig. 4, with Rietveld refinement data shown in Table 3 indicating phase quantities and goodness of fit (X2) of the data against structures from the Crystallography Open Database (COD). Fitting against the models is also shown graphically in supplementary data. All treatment times showed a clear transformation into a NASICON structure (Space Group (SG) 15, COD 1530660), which made up the majority of the samples. All samples exhibited residual precursors within their XRD patterns, and key Na3PO4 (SG 209 COD 1528204) and ZrO2 (SG 14 COD 1522143) peaks are indicated in Fig. 4; however, some can be hidden due to overlapping with NASICON peaks. Amorphous silica can be identified by the broad curve centring around 20°. This broad curve was most evident in the macro-derived samples for the lower treatment times (10 and 24 h) and was reduced with both sintering time and use of nanoprecursors. This suggested that the smaller powders allowed a more rapid transformation into NASICON. Quantities obtained from Rietveld refinement showed that ZrO2 was the most abundant impurity still evident in the sintered pellets. It was present at all treatment times and did not reduce with treatment duration. The presence of ZrO2 can potentially be due to both unreacted precursor and precipitation occurring as a result of volatilisation during the densification process. These cannot be distinguished from one another, but the increase over time suggests the latter mechanism is occurring due to the high temperature and duration of the process, which is supported by the literature. All samples showed minimal silica. Levels of Na3PO4 were generally low (apart from nano 24 h), but there was no trend of diminution over time. From the listed quantities, the data generally suggest more NASICON at the lower temperatures, but there is a broad background contributing to this, indicating there is some amorphous phase present. This is more obvious at the shorter treatment samples, suggesting that crystallinity increases with sintering time.

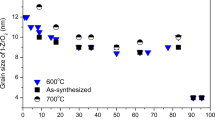

The microstructure of finished pellets is compared at different sintering time for both sets of precursors in Fig. 5. Higher-magnification images for 40 h sintering time only are shown in Fig. 6. The images show distinct grain structures whose growth was promoted through sintering. These grains had a cubic shape with the majority of the particles ranging in size from approximately 2–4 μm. Compared with the macro-precursors, the nanoprecursors gave grains with more consistent sizing and morphology, with more clearly defined cubic shapes and higher densification demonstrated by improved contact and packing between grains, although the differences were not substantial.

Impurities, due primarily to zirconia, can accumulate around the grain boundaries, resulting in the deterioration of ionic conductivity [21, 23], so a reduction in the extent of these grain boundaries should lead to higher conductivity. Analysis of particle sizes for both sets of precursors at 40-h sintering (Fig. 7) shows a wider distribution of particle sizes, more outliers and a number of abnormally large grains (> 10 μm in length) when using the macro-precursors. This abnormal grain growth could be the result of multiple grain growth speeds within the sample caused by anisotropic conditions such as anisotropic grain boundary energy or high grain boundary mobility [34]. A time temperature effect is suggested as a potential contributor to abrupt changes in grain size and boundaries [16, 35]. Since this was only evident in the macro-precursor, this suggests that this phenomenon is a function of both time and the precursor powder characteristics.

Distribution of particle sizes after 40-h sintering for nano- and macro-precursors—taken from images in Fig. 6—50 particle measurements at random locations

The density of the pellets at different sintering times is compared in Fig. 8. Densities are presented as a percentage with respect to the theoretical density of 3.27 g/cm3 [33]. The nanoprecursors gave a higher-density pellet due to improved contact and packing between grains, with a trend of slightly increasing density with sintering time from 95.0% up to a maximum of 96.3% of theoretical density (3.15 g/cm3). The macro-precursors showed very little change in density with sintering time, increasing slightly between 90.1 and 90.8% of theoretical density between 10 and 40 h of sintering. The density data correspond with the apparent porosity of the pellets made using the macro-precursors, with their more polydisperse morphologies. For comparison, the density achieved by Hayashi et al. [17] was 3.21 g/cm3 (98% of theoretical density).

Nyquist plots are shown for pellets at different sintering times in Fig. 9; for an accurate comparison, the data shown are normalised to account for the pellet dimensions (to Ω cm by dividing by thickness/surface area) and recorded at ambient temperature. The plots were distinctly grouped into two sets based on the size of precursors, with the nanoprecursors exhibiting lower Z′ values than the macro-precursors. For both types of precursor, there was a shift towards the low end of the Z′ axis as sintering time was increased which was more strongly evident for the nanoprecursors.

The near-straight line in the low-frequency range corresponds with interface components (electrode polarisation), and a single semicircle, due to the grain boundary, is apparent under the test conditions. Fitting of grain boundary (Rgb) and bulk resistances (Rb) at laboratory temperatures is therefore not precise, an issue reported previously by others [3, 11]. (However, two semicircles can be generated by reducing test temperature [3].) The total ionic conductivity can be calculated, using the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 9, from the intercept of the low-frequency end of the semicircle with the Z′ axis using the equation below, where t and A are the thickness and cross-sectional area of the sample.

Total ionic conductivities for pellets made using nano- and microprecursor are therefore shown in Fig. 10. The highest room temperature total ionic conductivity recorded in the study was 1.16 × 10−3 S cm−1 for nanoprecursors using the highest sintering duration of 40 h (at 1230 °C). Reducing the sintering times to 24 and 10 h gave reduced conductivities of 88 and 79% of this value, respectively. For all sintering times, the macro-particle precursors gave substantially lower total ionic conductivities, with a maximum of 0.63 × 10−3 S cm−1 for 40-h sintering, which again fell with reduced sintering time but to a much lesser extent than with the nanoprecursors (sintering times of 24 and 10 h gave conductivities of 98 and 95% of this value, respectively). Conductivity correlated with pellet density, with the macro-samples showing relatively little change in either property with sintering duration.

Discussion and conclusions

Using a solid-state synthesis route, NASICON (Na3Zr2Si2PO12) pellets produced from nanopowder precursors were found to produce improved morphology, higher density and therefore substantially higher ionic conductivities than those produced from larger macro-scale precursors. The maximum room temperature conductivity recorded in the study was 1.16 × 10−3 S cm−1 for nanoprecursors with a final sintering duration of 40 h (at 1230 °C). This is in the high end of the room temperature conductivity range of up to 1.2 × 10−3 S cm−1 reported for this form of NASICON [16, 17]. For the macro-precursors, the optimal conductivity was around 54% of this value at 0.63 × 10−3 S cm−1. Lee et al. [20] demonstrated a substantial increase in conductivity by reducing the size of the intermediate (but not precursor) powders, relying on a high-energy jet milling process. Despite this, conductivities (in the appropriate temperature range) were below those reported in this study in which small particles were introduced in the first stage of the process, without high-energy processing. In this study, prior to sintering there was only a slight difference in the particle size distributions of the powders derived from nano- and macro-precursors and this is unlikely to be responsible for the observed differences in densification and conductivity in the final pellets. There was, however, a substantially higher surface area in the pre-sintered powders produced from nanoprecursors, which was higher than that reported in the literature for more intensively treated samples and was similar to that reported for sol–gel derived precursors [3]. The smaller precursor particles, and resulting increase in surface area, resulted in an apparent enhancement of sintering properties of the powder, resulting in more homogenous grain growth, improved morphology and higher density, which consequently resulted in this lower resistance. The nanoprecursors used in the study are also of an appropriate size so that sintering benefits from the high surface-to-volume ratio.

In the current literature on the synthesis of NASICON, the powder characteristics of the precursor materials are typically not defined, yet this study has shown these have a major effect on the microstructure and performance. Additional milling techniques, or alternative routes to smaller particles, are reported and show significant results, but since no study exists into varying the particle size of the precursor powders themselves, a direct comparison is difficult. Given the complexity of the process, and the inherent problems in maintaining consistency in conditions such as milling intensity from one machine to another, a well-defined starting point, with particle size as the determining factor, could potentially offer a more predictable and scalable manufacturing process as well as reducing the extent and severity of milling processes. There are a substantial number of factors which affect conductivity and clear correlations do not always exist between parameters and the conductivity of the product. For example, while sintering time increases densification there is also an increase in evolution of ZrO2. Further optimisation would benefit from a better understanding of the grain boundaries as well as a comprehensive study of temperature and time effects, which might affect the different precursors differently [21].

In this study, the method of using nanoparticle powder precursors resulted in the performance being close to the highest published value of ionic conductivity of Na3Zr2Si2PO12 for solid-state processing, with a comparatively low intensity and duration milling process. There is scope to study the effects of trying different precursor particle size combinations and mixing the powders or a range of sizes to see the effect this has, as well as transferring this research to alternative forms of NASICON. From an industrial perspective, this has the potential of saving time, energy and cost for materials such as NASICON, which is ultimately important if these materials are to be adopted for large-scale energy storage.

References

Song S, Duong HM, Korsunsky AM, Hu N, Lu L (2016) A Na+ superionic conductor for room-temperature sodium batteries. Sci Rep 6:32330

Goodenough JB, Hong HY-P, Kafalas JA (1975) Fast Na+-ion transport in skeleton structures. Mater Res Bull 11(2):203–220

Naqash S, Ma Q, Tietz F, Guillon O (2017) Na3Zr2(SiO4)2(PO4) prepared by a solution-assisted solid state reaction. Solid State Ion 302:83–91

Niu Y-B, Yin Y-X, Guo Y-G (2019) Nonaqueous sodium-ion full cells: status, strategies, and prospects. Small 15:1900233

Ruan Y, Guo F, Liu J, Song S, Jiang N, Cheng B (2019) Optimization of Na3Zr2Si2PO12 ceramic electrolyte and interface for high performance solid-state sodium battery. Ceram Int 45:1770–1776

Hou W, Guo X, Shen X, Amine K, Yu H, Lu J (2018) Solid electrolytes and interfaces in all-solid-state sodium batteries: progress and perspective. Nano Energy 52:279–291

Huang Y, Zhao L, Li L, Xie M, Wu F, Chen R (2019) Electrolytes and electrolyte/electrode interfaces in sodium-ion batteries: from scientific research to practical application. Adv Mater 31:1808393

Noguchi Y, Kobayashi E, Plashnitsa LS, Okada S, Yamaki JI (2013) Fabrication and performances of all solid-state symmetric sodium battery based on NASICON-related compounds. Electrochim Acta 101:59–65

Ellis BL, Nazar LF (2012) Sodium and sodium-ion energy storage batteries. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci 16(4):168–177

Paściak G, Mielcarek W, Prociów K, Warycha J (2014) Structural and electrical studies of NASICON material for NOx sensing. Ceram Int 40(8 PART B):12783–12787

Park H, Jung K, Nezafati M, Kim CS, Kang B (2016) Sodium Ion diffusion in Nasicon (Na3Zr2Si2PO12) solid electrolytes: effects of excess sodium. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 8(41):27814–27824

Yu X, Xue L, Goodenough JB, Manthiram A (2019) A high-performance all-solid-state sodium battery with a Poly(ethylene oxide)-Na3Zr2Si2PO12 composite electrolyte. ACS Mater Lett 1:132–138

Guin M, Tietz F (2015) Survey of the transport properties of sodium superionic conductor materials for use in sodium batteries. J Power Sources 273:1056–1064

Fergus JW (2012) Ion transport in sodium ion conducting solid electrolytes. Solid State Ion 227:102–112

Hong HY-P (1976) Crystal structures and crystal chemistry in the system Na1+xZr2SixP3−xO12. Mater Res Bull 11(2):173–182

Naqash S, Sebold D, Tietz F, Guillon O (2018) Microstructure-conductivity relationship of Na3Zr2(SiO4)2(PO4) ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 102:1057–1070

Hayashi K, Shima K, Sugiyama F (2013) A mixed aqueous/aprotic sodium/air cell using a NASICON ceramic separator. J Electrochem 160(9):A1467–A1472

Kim Y, Kim H, Park S, Seo I, Kim Y (2016) Na ion-conducting ceramic as solid electrolyte for rechargeable seawater batteries. Electrochim Acta 191:1–7

Fuentes R, Figueiredo FM, Marques FMB, Franco JI (2001) Influence of microstructure on the electrical properties of NASICON materials. Solid State Ion 140(1–2):173–179

Lee S-M, Lee S-T, Lee D-H, Lee S-H, Han S-S, Lim S-K (2015) Effect of particle size on the density and ionic conductivity of Na3Zr2Si2PO12 NASICON. J Ceram Process Res 16(1):49–53

Choi S-D, Park J-W (1996) Preparation of NASICON powder and Electrolyte. Sens Mater 8(8):505–511

Narayanan S, Reid S, Butler S, Thangadurai V (2019) Sintering temperature, excess sodium, and phosphorous dependencies on morphology and ionic conductivity of NASICON Na3Zr2Si2PO12. Solid State Ion 331:22–29

Lee J-S, Chang C-M, Lee Y-I, Lee J-H, Hong S-H (2004) Spark plasma sintering (SPS) of NASICON ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 87(2):305–307

Zhang S, Quan B, Zhao Z, Zhao B, He Y, Chen W (2004) Preparation and characterization of NASICON with a new sol–gel process. Mater Lett 58(1–2):226–229

Martucci A, Sartori S, Guglielmi M, Di Vona ML, Licoccia S, Traversa E (2002) NMR and XRD study of the influence of the P precursor in sol–gel synthesis of NASICON powders and films. J Eur Ceram Soc 22(12):1995–2000

Essoumhi A, Favotto C, Mansori M, Satre P (2004) Synthesis and characterization of a NaSICON series with general formula Na2.8Zr2−ySi1.8−4yP1.2+4yO12 (0 ≤ y≤0.45). J. Solid State Chem 177(12):4475–4481

Ejehi F, Marashi SPH, Ghaani MR, Haghshenas DF (2012) The synthesis of NaSICON-type ZrNb(PO4)3 structure by the use of Pechini method. Ceram Int 38(8):6857–6863

Di Vona ML, Traversa E, Licoccia S (2001) Nonhydrolytic synthesis of NASICON of composition Na3Zr2Si2PO12: a spectroscopic study. Chem Mater 13(1):141–144

Porkodi P, Yegnaraman V, Kamaraj P, Kalyanavalli V, Jeyakumar D (2008) Synthesis of NASICON—a molecular precursor-based approach. Chem Mater 20(20):6410–6419

Park H, Kang M, Park Y-C, Jung K, Kang B (2018) Improving ionic conductivity of Nasicon (Na3Zr2Si2PO12) at intermediate temperatures by modifying phase transition behavior. J Power Sources 399:329–336

Fuentes RO, Figueiredo FM, Marques FMB, Franco JI (2001) Processing and electrical properties of NASICON prepared from yttria-doped zirconia precursors. J Eur Ceram Soc 21:737–743

da Silva JGP, Bram M, Laptev AM, Gonzalez-Julian J, Ma Q, Tietz F, Guillon O (2019) Sintering of a sodium-based NASICON electrolyte: a comparative study between cold, field assisted and conventional sintering methods. J Eur Ceram Soc 39(8):2697–2702

Fuentes RO, Marques FMB, Franco JI (1999) Synthesis and properties of nasicon prepared from different zirconia-based precursors. Cerámica y Vidr 38(6):631–634

Dillon SJ, Harmer MP (2009) Diffusion controlled abnormal grain growth in ceramics. Mater Sci Forum 558–559:1227–1236

Cantwell PR, Ma S, Bojarski SA, Rohrer GS, Harmer MP (2016) Expanding time-temperature-transformation (TTT) diagrams to interfaces: a new approach for grain boundary engineering. Acta Mater 106:78–86

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the EPSRC (UK) Grant number EP/N013727/1 and also by EP/R023581/1 and EP/N020863/1. SEM facilities were provided by the Swansea University AIM Facility; funded in part by the EPSRC (EP/M028267/1), the European Regional Development Fund through the Welsh Government (80708) and the Ser Solar project via Welsh Government. The authors would like to thank Nick Lavery, Swansea University, for assistance with equipment used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jalalian-Khakshour, A., Phillips, C.O., Jackson, L. et al. Solid-state synthesis of NASICON (Na3Zr2Si2PO12) using nanoparticle precursors for optimisation of ionic conductivity. J Mater Sci 55, 2291–2302 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-04162-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-04162-8