Abstract

Whereas existing indicators of standards of living neglect the dependence of individual well-being on other people’s welfare, this paper aims at constructing an income-based indicator taking welfare interdependencies into account. For that purpose, an extension of Usher’s longevity-adjusted income measure is developed, where the selfish representative agent is replaced by a two-generation representative household, whose members are connected by altruistic links. Longevity-adjusted income figures are shown, for the U.S. (1901–1999), to be significantly sensitive to the postulated altruism, so that conventional measures, by neglecting joint survival achievements, may underestimate actual improvements in living conditions. Methodological issues raised by the inclusion of interdependencies are also discussed, such as the increased difficulty, for indicators, to reflect the complexity and diversity of preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See the survey in Bergstrom (1997).

On the definition of altruism, see Eisenberg and Miller (1987).

See Schokkaert and Van Ootegem (2000) for empirical evidence on private donations.

On the difficulty to measure friendship and sociability, see Mercklé (2004).

A survey on the willingness to provide financial assistance in Japan reveals that, while about 92% of respondents would help their children, and 86–89% would help their parents, only 19 % would help friends, and only 1.5% would help complete strangers (see Horioka 2001).

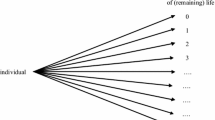

On Fig. 1, \(d_{j}^{i}\) denotes the probability of death for person i at period j.

The scenario ‘long life’ has a probability (\(1-d_{0}^{m}\)), while ‘short life’ has a probability \(d_{0}^{m}\) (under \(d_{1}^{m}=d_{1}^{w}= 1\)).

This equality occurs also when a society is fully disconnected (n i = 0 for all i). In the case of fully isolated people, one cannot distinguish an altruistic person from an egoistic one.

More formally, it is the ratio of the marginal utility of a rise in the risk of death for a family member over the marginal utility of an increase in the risk of death for the person himself.

We shall thus assume that the VSL is an estimate of the MRS between mortality risk and consumption as far as the private part of individual welfare is concerned.

Sources (for age-specific probabilities of death): Human Life-Table Database [2005]; calculations of joint survival curves by the author.

The probability of survival up to age 50 of a new-born boy has grown from 0.57 to 0.91 over that period.

Sources for real GDP statistics per head: Maddison (2004). Sources for population structures: The Human Mortality Database (available online at http://www.mortality.org/).

Throughout this Section, longevity-adjusted income figures are based on population-weighted ‘single’ average life expectancies (men and women) for 10 age-groups (0—5 years, 6–17, 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85–104), which are computed on the basis of age-specific and gender-specific life expectancies (with weights reflecting the demographic importance of each age and gender within each age-group).

Population-weighted joint life expectancies statistics are computed on the basis of the average survival conditions of the 10 age-groups mentioned above, with weights reflecting the demographic importance of each sub-case. For convenience, it is supposed that parents belong—unlike children—to the same age-group.

Family-structure parameters are based on the statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau (2005) on the size and composition of households.. The choice to rely on household statistics rather than on family statistics comes from the fact that the precise age and gender compositions of families are not available, so that the most adequate approach is to rely on household data, which cover the entire country, and, then, use age-structure statistics to derive the age and gender composition of the average household.

References

Anand, S., & Ravallion, M. (1993). Human development in poor countries: On the role of private income and public services. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7, 133–150.

Arends-Kuenning, M., & Duryea, S. (2006). The effect of parental presence, parents’ education and household headship on adolescents’ schooling and work in Latin America. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 27, 263–286.

Arthur, W. B. (1981). The economics of risks to life. American Economic Review, 71, 54–64.

Becker, G. S., Philipson, T. J., & Soares, R. R. (2005). The quantity and quality of life and the evolution of world inequality. American Economic Review, 95(1), 277–291.

Bergstrom, T. C. (1997). A survey of theories of the family. In M. R. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of population and family economics (Vol. 1A, pp. 21–79). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Costa, D. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2004). Changes in the value of life, 1940–1980. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 29, 159–180.

Costa, D. L., & Steckel, R. H. (1997). Long-term trends in health, welfare, and economic growth in the United States. In R. H. Steckel & R. Floud (Eds.), Health and welfare during industrialization (NBER Project Report, pp. 47–89). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Crafts, N. F. R. (1997). The Human Development Index and changes in standards of living: Some historical comparisons. European Review of Economic History, 1, 299–322.

Crafts, N. F. R. (2002). UK national income, 1950–1998: Some grounds for optimism. National Institute Economic Review, 181, 87–95.

Dasgupta, P. S. (1993). An inquiry into well-being and destitution. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1999). How beneficent is the market? A look at the modern history of mortality. European Review of Economic History, 3, 257–294.

Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). Empathy, sympathy, and altruism: Empirical and conceptual links. In N. Eisenberg & J. Strayer (Eds.), Empathy and its development (pp. 292–316). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Eisner, R. (1988). Extended accounts for national income and product. Journal of Economic Literature, 26, 1611–1684.

Horioka, C. Y. (2001). Are the Japanese selfish, altruistic, or dynastic? Japanese Economic Review, 53, 26–54.

Human Life-Table Database (2005). Life-Tables for the United States of America, 1901–1999 [original source: Bell, F. C., & Miller, M. L. Life tables for the United States Social Security area 1900–2100. Actuarial Study 116]. Retrieved September 5, 2005, from http://www.lifetable.de/

Johansson, P.-O. (1995). Evaluating health risks: An economic approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jones-Lee, M. W. (1989). The economics of safety and physical risks. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Kolodinsky, J. & Shirey, L. (2000). The impact of living with an elder parent on adult daughter’s labor supply and hours of work. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 21, 149–175.

Linnerooth, J. (1979). The value of human life: A review of the models. Economic Inquiry, 17, 52–74.

Maddison, A. (2004). Historical statistics, 1-2001 AD. Retrieved December 15, 2005, from http://www.eco.rug.nl/ggdc

Mercklé, P. (2004). La Sociologie des réseaux sociaux. Paris: La Découverte.

Miller, T. R. (2000). Variations between countries in values of statistical life. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 34, 169–188.

Moon, S.-J., & Joung, S.-H. (1997). Expenditure patterns of divorced single-mother families and two-parent families in South Korea. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 18(2), 147–162.

Morris, M. D. (1979). Measuring the condition of the world’s poor. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

Needleman, L. (1976). Valuing other people’s lives. Manchester School, 44, 309–342.

Nordhaus, W. D. (2003). The health of nations: The contribution of improved health to living standards. In K. M. Murphy & R. Topel (Eds.), Measuring the gains from medical research: An economic approach (pp. 19–39). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Nordhaus, W. D., & Tobin, J. (1973). Is growth obsolete? In M. Moss (Ed.), The measurement of economic and social performance (NBER Studies in income and wealth, Vol. 38, pp. 509–532). New York: NBER.

Perry-Jenkins, M., & Gillman, S. (2000). Parental job experiences and children’s well-being: The case of two-parent and single-mother working-class families. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 21, 123–147.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Randolph, K. A., Rose, R. A., Fraser, M. W., & Orthner D. K. (2004). Examining the impact of changes in maternal employment on high school completion among low-income youth. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25, 279–299.

Sandberg, L. G., & Steckel, R. H. (1997). Was industrialization hazardous to your health? Not in Sweden! In R. H. Steckel & R. Floud (Eds.), Health and welfare during industrialization (NBER Project Report, pp. 127–159). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Schokkaert, E., & Van Ootegem, L. (2000). Preference variation and private donations. In L. A. Gerard-Varet, S-C. Kolm, & J. Mercier-Ethier (Eds.), The economics of reciprocity, giving and altruism (International Economic Association Conference Volume, pp. 78–95). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sen, A. K. (1973a). On the development of basic income indicators to supplement GNP Measures. United Nations Bulletin for Asia and the Far East, 24, 1–11.

Sen, A. K. (1973b). Behaviour and the concept of preference. Economica, 40, 241–259.

Sen, A. K. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Sharpe, D. L., Abdel-Ghany, M., Kim, H.-Y., & Hong, G.-S. (2001). Alcohol consumption decisions in Korea. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22, 7–24.

Tsang, L., Harvey, C., Duncan, K., & Sommer, R. (2003). The effect of children, dual earner status, sex role traditionalism and marital structure on marital happiness over time. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 24, 5–26.

U. S. Census Bureau (2005). Families and living arrangements. Historical Time Series. Households (Table HH-6). Retrieved September 5, 2005, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam.html

Usher, D. (1973). An imputation to the measure of economic growth for changes in life expectancy. In M. Moss (Ed.), The measurement of economic and social performance (NBER, Studies in income and wealth, Vol. 38, pp. 193–226). New York: NBER.

Usher, D. (1980). The measurement of economic growth. New-York: Columbia University Press.

Viscusi, W. K. (1993). The value of risks to life and death. Journal of Economic Literature, 31, 1912–1946.

Viscusi, W. K., & Aldy, J. E. (2003). The value of a statistical life: A critical review of market estimates throughout the world. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 27, 5–76.

Weisbrod, B. A. (1962). An expected measure of economic welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 70, 355–367.

Williamson, J. G. (1984). British mortality and the value of life, 1781–1931. Population Studies, 38, 157–172.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Pierre Pestieau, Jean-Pierre Urbain and two anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ponthiere, G. Monetizing Longevity Gains under Welfare Interdependencies: An Exploratory Study. J Fam Econ Iss 28, 449–469 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-007-9066-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-007-9066-7