Abstract

The main aim of this study was to compare the polychaete communities in two similar polar areas: an Arctic fjord, Hornsund (Svalbard) and an Antarctic fjord, Ezcurra Inlet (South Shetlands). This is the first attempt to compare Arctic and Antarctic diversity based on fully comparable datasets. Forty van Veen grab samples were collected in each fjord: twenty replicates were taken in each of two fjord areas characterized by a different level of glacial disturbance—in the inner (glacial bay) and outer (fjord mouth) region of both fjords, from depths of about 100 m in 2005 (Hornsund) and in 2007 (Ezcurra Inlet). In the glacial bays, species richness and diversity were significantly higher in Ezcurra Inlet than in Hornsund due to higher rate of glacial disturbance in the latter one. In the outer areas, species richness was similar in both fjords, although diversity values were higher in Ezcurra Inlet. Polychaete species richness in the habitats characterized by similar level of disturbance (outer areas of the fjords) was the same in both polar regions. At this small scale, where community drivers are very similar, the species richness seems to be independent from the local or regional species pool.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Until recently, it was commonly assumed that the benthic diversity in the Antarctic is substantially higher than in the Arctic (Dayton et al., 1994; Knox & Lowry, 1977; Crame, 1997; Brandt, 2001). Different geological age and different level of geographic isolation of those two regions and thus their evolutionary history were the main basis for this assumption. Arctic marine fauna is relatively young. The present environmental characteristics of the Arctic region were shaped by Pliocene cooling about 3 million years ago and some later Quaternary events (Dayton, 1990; Piepenburg, 2005). However, the current benthic fauna probably colonized the Arctic shelf only after the last glacial maximum, no more than 13,000 years ago (Clarke & Crame, 2010). In contrast, the Southern Ocean benthic fauna evolved in stable conditions and isolation since the establishment of the Drake Passage and Antarctic Circumpolar Current 34 million years ago (Barrett, 1999). Antarctic benthic fauna is often described as more diverse and characterized by higher level of endemism than the Arctic fauna (e.g., Knox & Lowry, 1977; Dayton et al., 1994). The homogeneity of the Arctic benthic habitats and higher rates of disturbance were also pointed as possible reasons for differences in diversity between both regions (Dayton, 1990). Yet, these common assumptions have recently been questioned and considered as a result of overgeneralization (Piepenburg, 2005). Recent taxonomic inventories of both polar regions demonstrated that in general the number of species is similar. De Broyer et al. (2011) listed 5,800 benthic species in the Southern Ocean, while the number of Arctic species was estimated to be about 4,800 (Sirenko, 2001; Piepenburg et al., 2011). Moreover, some studies suggested that both Arctic and Antarctic diversity are still underestimated (e.g., Carr, 2012; Pabis et al., 2014). Nevertheless, these totals can provide only a very superficial knowledge about differences and similarities between those two polar regions, and diversity may further vary depending on the taxonomic or ecological group. So far, there have only been few attempts to compare benthic diversity on Arctic and Antarctic shelves, and those included only large scale syntheses comparing either the Arctic and Antarctic as a whole (Knox & Lowry, 1977), or large basins, like the Laptev Sea and Weddell Sea (Piepenburg et al., 1997; Starmans et al., 1999; Starmans & Gutt, 2002; Sirenko, 2009). Moreover, those analyses were mostly focused on mega-epibenthic fauna, not always collected with quantitative sampling gear. Even single studies on the intermediate scale of polar fjords (Błażewicz-Paszkowycz & Sekulska-Nalewajko, 2004; Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al., 2007) were based on not fully comparable datasets since samples were collected from different substrates and/or different depths. Thus, rigorous comparisons of similar depths and types of habitats are essential as the only way to provide any further meaningful inventories (Clarke & Crame, 2010).

Glacial fjords are hosting a very rich and diverse fauna with many species associated only with this type of habitats (Włodarska-Kowalczuk & Pearson, 2004; Siciński et al., 2011; Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al., 2012; Grange & Smith, 2013). Those semi-closed inlets are affected by chronic disturbance processes associated with the influence of subglacial streams, resulting in high inflow of inorganic suspension and silting of bottom sediments. This is considered as the main reason of the fjords’ vulnerability to environmental changes associated with on-going climate warming (Smale & Barnes, 2008; Węsławski et al., 2011). In this study, we compared two similar polar inlets: Hornsund, Svalbard, and Ezcurra Inlet, South Shetlands. Hornsund is an All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory site (ATBI) and is an important area for monitoring the effects of climate change (Warwick et al., 2003). Ezcurra Inlet is a part of Admiralty Bay—the most comprehensively studied basin in the rapidly changing region of the Western Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) (Siciński et al., 2011). Both fjords have been intensively sampled for the last 35 years and can be treated as model polar fjord ecosystems. Information about the benthic diversity of those basins were recently summarized by Kędra et al. (2010a) and Siciński et al. (2011) as a result of two large polar marine programs: Marine Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning (MarBEF) and Census of Antarctic Marine Life (CAML).

Polychaetes are an ecologically diverse group that often dominate in terms of species richness, abundance, and biomass in marine benthic communities all over the world (e.g., Knox, 1977; Ansari et al., 1991; Hutchings et al., 1993; Mackie & Oliver, 1993; Smith, 2000), also in polar soft bottom communities (Kendall et al., 2003; Piepenburg, 2005; Clarke & Crame, 2010; Pabis et al., 2011). They are considered excellent surrogates of overall biodiversity and indicators of ecosystem response to changes in environmental conditions (Olsgard & Somerfield, 2000; Olsgard et al., 2003; Giangrande et al., 2005; Włodarska-Kowalczuk & Kędra, 2007). Currently, there are 590 polychaete species included in the Register of Antarctic Marine Species (De Broyer et al., 2011), while the number of species recognized in the Arctic reaches almost 660 (Sirenko, 2001). For those reasons, polychaetes were chosen as a model group in this study.

The aim of this study is to compare the soft bottom polychaete abundance, species richness, diversity, and functional groups in Arctic and Antarctic soft bottom habitats affected by different level of glacial disturbance: glacial bays and fjord mouth. Trustworthy diversity assessment of those two fjords based on the comparable material should bring new insights into the debate on diversity of the marine seafloor in polar regions. It could also substantially influence creation of the future climate warming scenarios of changes in benthic community structure of polar fjords.

Materials and methods

Study area

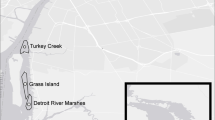

Hornsund

Hornsund is a medium-sized glacial fjord located on the southwest coast of Spitsbergen (Svalbard, Arctic, 77°N) with a maximum depth of about 260 m. It is influenced by cold Arctic waters of the Sørkapp Current and warmer Atlantic waters of West Spitsbergen Current (Swerpel, 1985). The inner glacial bay, Brepollen, is partially isolated by the Treskelen Peninsula (Fig. 1; Table 1) and is affected by meltwater inflow from the five large tidewater glaciers (Weslawski et al., 1995). High values of mineral suspension in this area result in high water turbidity (Gorlich et al., 1987; Piwosz et al., 2009) and a reduced euphotic layer (Urbański et al., 1980). Compared to the outer part of the fjord, the sedimentation in Brepollen is much higher (35 vs. 0.1 cm year−1), while the mineral suspension content in Hornsund waters was estimated to be up to 1,000 and about 20 mg dm−3, respectively (Gorlich et al., 1987). Mud dominates bottom sediments but sandy deposits and dropstones often occur in the outer fjord area (Rudowski & Marsz, 1996; Szczuciński & Schettler, unpublished results). All those factors affect primary production and organic matter content in the fjord resulting in reduced amounts of total organic carbon (TOC) in the areas located in the vicinity of glaciers (Gorlich et al., 1987; Eilersten et al., 1989; Piwosz et al., 2009). TOC reaches values between 1.75 and 1.99% in the inner basin and between 1.37 and 1.84% in the outer part of the fjord (Schettler & Szczuciński, unpublished data).

Ezcurra Inlet

Ezcurra Inlet is a part of Admiralty Bay. It is a semi-closed fjord of tectonic origin located at King Georg Island (South Shetlands, Antarctic, 63°S) with maximum depth of about 280 m (Marsz, 1983). The central basin of Admiralty Bay and outer areas of the inner inlets (Ezcurra, Martel, and MacKellar) are influenced by warmer and less saline waters from the Bellingshausen Sea and colder and more saline Weddell Sea waters (Gordon & Nowlin, 1978; Tokarczyk, 1987). The Ezcurra Inlet is a narrow fjord with tidewater glaciers distributed along its north-west coastline with the largest glaciers located in the inner region (Fig. 1). The amount of mineral suspension is decreasing from the inner glacial bays (>100 mg dm−3) toward the outlet area (about 15 mg dm−3) (Pęcherzewski, 1980; Siciński et al., 2011). High water turbidity was recorded in the inner region of this fjord contrasting with the lower turbidity in the fjord mouth (Lipski, 1987). Those differences in sedimentation processes are causing differences in sediment type: highly disturbed glacial bays are characterized by silt and clay sediments, while the outer region has sandy mud, poorly sorted deposits with larger amount of skeletal fractions (Siciński, 2004; Siciński et al., 2011; Campos et al., 2013). The differences between the inner and outer part are enhanced by bottom topography (Table 1): both parts of the fjord are separated by a submerged sill which partially isolates two areas (Marsz, 1983). The glacial sedimentation inflow is influencing the primary production in the waters of this inlet resulting in low concentrations of phytoplankton especially in the inner part of Ezcurra Inlet (Tokarczyk, 1986).

Sampling

Sampling was conducted in Hornsund and Ezcurra Inlet in July of 2005 and March of 2007, respectively, with standardized sampling methods. Two sampling areas were selected in regions of the fjords characterized by different levels of glacial disturbance. The inner area (glacial bay) and outer region (fjord mouth) of both fjords were sampled at depths of about 100 m (Ezcurra Inlet: inner 90–130 m, outer 100–130 m, Hornsund: inner 100–120 m, outer 100–115 m). In each area, 20 van Veen grabs (0.1 m2) were collected (5 stations in each area, 4 replicates at each station) (Fig. 1). Altogether 80 quantitative samples were gathered, 40 samples in each fjord. Samples were sieved through 0.5-mm mesh and fixed in 4% buffered formalin solution. An additional van Veen grab for sediment analysis (granulometry and TOC) was collected at each station. Those results are included in habitat descriptions provided in Table 1.

Laboratory and data analysis

In the laboratory, samples were sorted and polychaetes were picked, identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level and counted. Almost all specimens were identified to species level and only cirratulids to generic level. The closely related genera Aphelochaeta and Chaetozone, morphologically very similar taxa, are often destroyed, lack many important diagnostic features and require special collecting techniques. In order to compare functional groups diversity between the habitats and fjords, each species was assigned to the functional group following the classification proposed by Fauchald & Jumars (1979) which include feeding modes, mobility type, and type of buccal organ. This method of describing polychaete functional diversity is known as good tool for environmental assessment especially in characteristic of communities affected by various disturbance processes (Pagliosa, 2005).

Species accumulation curves with 95% confidence intervals were created for each area of both fjords using the formulae of Colwell (2009). Indices of species richness (S—number of species per sample, Margalef—d), evenness (Pielou—J), and diversity (Shannon index log e H and Hurlbert rarefaction index (ES[n], where n = 50)) were calculated (Hurlbert, 1971; Magurran, 2004). Levene’s test was used to estimate the homogeneity of variance. Since the variances were not homogenized, differences between S, d, Shannon, and ES[50] indices in the outer areas of both fjords were tested with nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. For all other indices, differences were tested with one-way ANOVA (STATISTICA 6 package). Information about species rarity is important in diversity estimates of benthic communities and was pointed as an important element of habitat-based analysis (Ellingsen et al., 2007; Fontana et al., 2008). Therefore, the number and percentage of rare species, defined as singletons (represented by only one individual) or doubletons (represented by only two individuals), were calculated for each area.

Results

Altogether 23,103 specimens were collected in Hornsund (HD), and 24,121 in Ezcurra Inlet (EI) (Table 2). The total number of polychaete species was similar in both fjords: 88 species from 30 families were found in Hornsund and 90 species from 26 families in Ezcurra Inlet. The most speciose families were: Syllidae (HD: 6, EI: 11), Terebellidae (HD: 8, EI: 10), and Sabellidae (HD: 6, EI: 9) (Fig. 2). The total number of species differed between the inner areas (21 species in HD, 58 in EI) but was very similar in the outer regions (81 in HD and 83 in EI) (Table 2). Those differences were reflected in the number of species from each functional group recorded in each of the studied sites. All functional groups were found in the inner area of the Ezcurra Inlet while in the inner area of Hornsund only six functional groups were present (Table 3). The number of species of sessile, surface deposit feeding (SST) and motile non-jawed burrowing (BMX) polychaetes was higher in the glacial bays in Ezcurra Inlet than in Hornsund (SST 11 vs 1 species, BMX 11 vs 5 species). All 7 functional groups were found in both outer areas and the total number of species in almost all categories was very similar (Table 3). Percentage of rare species was very similar in both fjords. In the inner areas singletons were slightly more numerous in Ezcurra Inlet (20%) than in Hornsund (14%) while in the outer areas of both fjords singletons comprised up to about 26% of all species (Table 2).

There were significant differences in density and all species richness and diversity indices except from the Shannon index between the inner areas of both fjords (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05). Species richness (S) and ES[50] in Ezcurra Inlet’s glacial bay were higher than in the inner area of Hornsund. On the contrary, the evenness values in the inner area of Ezcurra Inlet was lower than in Hornsund. Shannon index was very similar in both fjords (Table 2; Fig. 3).

In the outer areas, diversity (ES[50], Shannon index) was significantly higher in Ezcurra Inlet than in Hornsund (Man Whitney U test P < 0.05). There were no differences in species richness (S), however, the Margalef index was significantly higher in the outer area of Ezcurra Inlet (Man Whitney U test P < 0.05). Differences for evenness and density were also noted between the outer areas. Evenness was significantly higher in Ezcurra Inlet, while density was higher in Hornsund (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05) (Table 2, Fig. 3). Species–accumulation curves were close to asymptotic level in the Sobs and Chao2 richness estimators in the inner area of Hornsund (Figs. 4, 5). The curves were steeper in the other three areas.

Inner and outer areas of both fjords differed in terms of functional groups density. In the glacial bays, the most important differences were found for burrowers (BMX and BSX), carnivores (CMJ), and suspension feeders (FST). In the fjord mouth, the most important differences concerned carnivores (CMJ), suspension feeders (FST), but also surface deposit feeders (SDT, SMX) and herbivores (HMJ) (Table 3).

Discussion

The discussion about the differences and similarities between Arctic and Antarctic diversity remains open. Our study did not demonstrate an unequivocal result. Significant differences were found mostly for the inner areas of both polar fjords. Higher species richness and diversity in Ezcurra Inlet glacial bay are most probably related to much lower rate of disturbance in Ezcurra Inlet than in Hornsund (Table 1). The mineral suspension content in inner areas of Hornsund can be even an order of magnitude higher than in Ezcurra Inlet (Gorlich et al., 1987; Siciński et al., 2011). The meaningful conclusions for the regional differences can, therefore, be only drawn from the diversity comparisons between the outer areas, where the level of disturbance was similar in both fjords. Values of the most important disturbance agents like sediment type and sedimentation inflow were very similar despite the differences in size of both fjords (Table 1). In the fjord mouth, the total species number, the species richness of each functional group, and the number of species per sample were similar in both fjords, however, the diversity values were significantly higher in Ezcurra Inlet. On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that widely used diversity indices like Shannon and Hurlbert index might be influenced by the dominance of certain species (Gray, 2000; Salas et al., 2004) so the basic diversity measures like number of species per sample could be more useful in such bipolar comparisons.

Earlier studies conducted at the intermediate scale are also inconsistent. For example, higher α diversity of tanaidaceans (Shannon index, number of species per sample) was found in Admiralty Bay than in Kongsfjorden (Błażewicz-Paszkowycz and Sekulska-Nalewajko, 2004), but this group of crustaceans plays a minor role especially in the Arctic benthos (Brandt, 1997) and cannot be treated as surrogate of overall diversity. Nevertheless, the maximal values of tanaidacean species richness per sample were similar in both fjords. The only study of infaunal macroinvertebrates showed similar polychaete diversity between Admiralty Bay and two Arctic fjords: Kongsfjorden and van Mijenfjord (Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al., 2007). Results of both studies can be, however, biased due to incomparable datasets since samples from different habitats were taken into account in the analysis. Moreover, the results might be influenced by to the thirteen to even twenty years time span between the sampling campaigns, especially when rapid climate changes, that occurred during this period, are taken into account (Walsh, 2009).

Other attempts of comparison between Arctic and Antarctic diversity of benthic fauna also revealed some inconsistencies. The total number of species in various groups of macroepifauna in the methodologically standardized studies was higher in the Antarctic (Piepenburg et al., 1997; Starmans et al., 1999; Starmans & Gutt, 2002) while regional (Sirenko, 2001; De Broyer et al., 2011) and local (Weddell Sea vs Lazarev Sea) (Sirenko, 2009) comparisons of species lists showed similar species richness in both polar regions. It might suggest that some of the Arctic taxa have a higher share of rare species. However, α diversity (single sample results) differs depending on the groups studied and/or sampling gear used. For example, Piepenburg et al. (1997) demonstrated that echinoderm diversity was higher in the Weddell Sea than on the north-eastern Greenland shelf, yet that study was based on Agassiz trawl samples. It included stations from a depth range of 200–1,200 m with both shelf and slope fauna and did not take into account large differences between the depth of the Arctic (200–500 m) and Antarctic (500–1,000 m) shelf. On the contrary Starmans et al. (1999) and Starmans & Gutt (2002) did not find any significant differences in megaepibenthic α diversity between Arctic and Antarctic seas at shelf depths (underwater video survey). Brandt (2001) demonstrated higher densities of peracarids in the Arctic compared to the Antarctic and linked this observation with different age of those communities and lower maturity of the Arctic ecosystem which could therefore be dominated by fewer species occurring in higher densities. Our results did not confirm this opinion. In the outer areas, the total number of species, number of species per sample, and number of singletons were almost the same in both investigated fjords.

Higher habitat heterogeneity associated with the presence of large sponges, ascidians, and bryozoans, which are creating a complex habitat for other epifaunal organisms, was pointed as the most probable reason of higher diversity of Antarctic macro- and mega-epibenthic fauna (Barnes, 1994; Gutt & Schickan, 1998; Gutt & Piepenburg, 2003). Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al. (2007) emphasized that spatial heterogeneity of sedimentary habitats is in fact comparable between Arctic and Antarctic shelf. However, the number of soft bottom microhabitats seems to be higher in Ezcurra Inlet than in investigated Arctic fjords (Kongsfjorden and Hornsund). Studies of polychaete diversity in Ezcurra Inlet and in Admiralty Bay as a whole showed high number of polychaete assemblages associated with different microhabitats (Siciński, 2004; Pabis & Siciński, 2010), while in Kongsfjorden the character of bottom deposits was less diversified resulting in more simple assemblage differentiation into three main faunal groupings associated with the inner, middle and outer areas of this inlet (Włodarska-Kowalczuk & Pearson, 2004). A similar pattern was also observed in Hornsund (Kędra et al., 2013). Our small scale study was focused on two clearly defined similar habitats to allow for more reliable comparisons. At this scale, where community drivers (sedimentation inflow, character of bottom sediments, organic matter content) influencing the fauna are very similar, we can expect similar species diversity. Those patterns could be independent of the evolutionary history of the whole regions (Hillebrandt & Blenckner, 2002). On the other hand, the regional species pool can be reflected at the local scale (Cornell & Lowton, 1992). Also, when the local area is smaller in proportion to the whole region it is less influenced by drivers shaping the regional species pool (Hillebrandt & Blenckner, 2002). Moreover, the Arctic and Antarctic species pools are independent and there is no overlap in species composition which was suggested as very important element in local–regional diversity comparisons (Ricklefs, 2000). Some of the recent molecular studies demonstrated the presence of bipolar species in some of the benthic invertebrate groups like amphipod crustaceans (Havermans et al., 2013), however, this result should be considered rather an exception from the rule (Brandt et al., 2012). There is a growing number of examples of polychaete species previously considered bipolar or cosmopolitan taxa turning out to be in fact species complexes (Scaps et al., 2000; Bleidorn et al., 2006; Barroso et al., 2010), and detailed taxonomic studies resulted in re-descriptions and changes in their taxonomic status (Parapar & Moreira, 2008). Nevertheless, Witman et al. (2004) showed that the factors operating at different spatial scales can be responsible for the diversity patterns. Therefore, scrutinizing the influence of the local conditions (including competition, level of disturbance, environmental factors) and their possible role in shaping regional species pools in the Arctic and the Antarctic is necessary.

The significance of the local and regional drivers in polar marine faunas still needs further investigations. Witman et al. (2004) demonstrated that 70% of local richness could be explained by the richness of the regional species pool. Our study showed contradictory results. The discrepancy between local (habitats) and intermediate (fjords) species richness is evident. The total number of polychaete species in Hornsund and Ezcurra Inlet differs strongly. 162 species were recorded in the whole Admiralty Bay (Siciński et al. 2011), 138 species were recorded in Ezcurra Inlet (Siciński, 1986, Hartmann-Schoder & Rosenfeldt, 1988, 1989; Siciński 2004; Pabis & Siciński, 2010; Siciński et al., 2012), while 93 species were found in Hornsund (Kędra et al., 2010a). Similar differences in general number of species were also highlighted in comparisons of peracarid diversity of those two fjords (Jażdżewski et al., 1995; Błażewicz-Paszkowycz & Sekulska-Nalewajko, 2004). A recently updated list based on more comprehensive studies showed similar results (Hornsund: Amphipoda 70 species, Tanaidacea 3 species, Admiralty Bay: Amphipoda 172 species, Tanaidacea 14 species (Kędra et al., 2010a; Sicinski et al., 2011). Those results are still quite similar for the Ezcurra Inlet alone (at least 110 species of Amphipoda Siciński et al. 2012, A. Jażdżewska unpublished results, and 8 species of Tanaidacea M. Błażewicz-Paszkowycz unpublished results). Svalbard polychaete diversity was estimated to be about 259 species (Palerud et al., 2004; Voronkov et al., 2013). The number of polychaete species known from South Shetlands was never summarized, however, basing on combined information from various sources (Hartman, 1964, 1966, 1967; Averincev, 1972; Hartman-Schroder, 1986; Hartman-Schroder & Rosenfeldt, 1988; Gallardo et al., 1988; Orenzsanz, 1990; Parapar & San-Martin, 1997; San Martin & Parapar, 1997; San-Martin et al., 2000; Lovell & Trego, 2003) it can be assumed that there are at least 230 species known from this area, so the result is similar to the one recorded in Svalbard waters. Total number of species in both fjords and archipelagos was not equally reflected in the richness on the habitat level in our small scale study. At large time scale almost all species from a regional species pool are expected to invade every community (Hillebrand & Blenckner, 2002). It could be justified especially for the animals with relatively high dispersal ability like polychaetes (mostly planktonic larval stage) (Rouse & Pleijel, 2001). On the other hand, Bhaud (1998) demonstrated that polychates with long-lasting planktonic larval development do not necessarily have a larger geographic range which is further confirmed by the large differences in species composition between neighbouring fjords located along the Western Antarctic Peninsula (Grange & Smith, 2013).

Our data, including the large number of singletons and doubletons found in both fjords as well as species accumulation curves suggest that there are more species that can be potentially found in the investigated habitats, especially in the outer areas. Rare species are important for supporting stability of ecosystem functioning and at the same time are often highly vulnerable to environmental changes and disturbance events (Ellingsen et al., 2007). Their number as well as their role in the polar marine habitats still need more scientific attention especially in the context of ongoing rapid climate change which could result in an increased rate of disturbance in polar fjords. Węsławski et al. (2011) postulated that climate change may cause a homogenization of benthic habitats. It is possible that such changes may be reflected at first in the distribution of rare species which have lower environmental tolerance and high habitat specificity (Ellingsen et al., 2007). In our study, the number of rare species was much lower in the glacial bays, especially in Hornsund where level of glacial disturbance is higher than in Ezcurra Inlet (Table 1).

Our comparison of diversity within the same habitats between Ezcurra Inlet and Hornsund pose also important queries in the discussion on climate influence on benthic fauna in polar fjords. The Arctic as well as the region of the Antarctic peninsula (WAP) are amongst the fastest warming areas on Earth (Walsh, 2009). Influence of rapid warming on the community structure and diversity of Arctic benthic fauna were already documented (e.g., Kędra et al., 2010b; Grebmeier, 2012), but there are no similar studies in the Southern Ocean. Węsławski et al. (2011) highlighted that Arctic warming might influence not only diversity of benthic communities but cause also the functional simplification (with increasing dominance of non selective deposit feeders). Such changes could be especially pronounced in the inner areas of the fjords. Increasing sedimentation associated with warming in the WAP region could result in modification in community structure. It could be assumed that inner areas of Ezcurra Inlet (with still relatively high functional diversity) might in a future resemble the current state of the Hornsund glacial bays (area with clearly lower diversity of functional groups).

On the other hand, it was recently emphasized that the predictions and scenarios presented for the Arctic regions are not directly applicable to the Antarctic ecosystem (Smale & Barnes, 2008). For the infaunal communities in glacial fjords, especially in the outer areas where the level of disturbance is similar, the climate change influence on benthic fauna is pronounced in a similar way. Our study was based on the datasets collected in both fjords at the same time, when climate change was already visible. According to Grange & Smith (2013), Admiralty Bay and other fjords at South Shetlands are in later stage of climate warming compared to the fjords located further south in the WAP region and are more similar to the Spitsbergen fjords. Our study further confirms this opinion. In consequence climate related changes, which will be observed in Ezcurra Inlet and also in Hornsund, can reflect future modifications of the more southern Antarctic basins. Those sites can function as natural laboratories where increasing dynamics of glacial processes will influence the marine biota, giving us the opportunity to predict future scenarios and discuss their applicability in different inlets distributed along the Antarctic Peninsula.

Conclusions

On the habitat level, in the areas characterized by similar environmental properties and similar level of disturbance (outer areas of the fjords), species richness of soft bottom polychaete communities is almost the same in the Arctic and in the Antarctic. That seems to be independent from the species pool of the whole fjords and probably not influenced by differences in evolutionary history of both polar regions. Those results demonstrate how important role local conditions play in shaping benthic diversity in polar regions. Our results suggest very complex interactions occurring even at relatively small scale which makes the reliable conclusions on the regional scale difficult and far from being completed. The discrepancy between the habitat scale (Hornsund inner and outer—88 species, Ezcurra Inlet inner and outer—90 species; this study) and the intermediate scale of whole fjords (Hornsund—93 species, Ezcurra Inlet—138 species) (Siciński, 1986; Hartmann-Schoder & Rosenfeldt, 1988, 1989; Siciński, 2004; Kędra et al., 2010a; Pabis & Siciński, 2010; Siciński et al., 2012) imply that further analysis should include studies of processes associated with migrations of species between the habitats, as well as the influence of pre- and post-settlement events, competition, development modes, and dispersal abilities. Further studies should also include comparisons of various types of benthic habitats. It will allow for more comprehensive evaluation of differences and similarities of benthic diversity in polar regions and make extrapolations from habitat to local and regional scale more adequate.

References

Ansari, Z. A., C. U. Rivonker, P. Ramani & A. H. Parulekar, 1991. Seagrass habitat complexity and macroinvertebrate abundance in Lakshadweep coral reef lagoons, Arabian Sea. Coral Reefs 10: 127–131.

Averincev, V. G., 1972. Donnyje mnogoscetinkovyje cervi Errantia Antarktiki I Subantarktiki po materialam Sovetskoj Antarktice- skoj Ekspedicii. [Benthic polychaetes Errantia from the Antarctic and Subantarctic collected by the Soviet Antarctic Expeditions.] Issledovanija Fauny Morej. 11 (19). Rezultaty Biologiceskich Issledovanij Sovetskich Antarkticeskich Ekspedici 5: 88–293.

Barnes, D. K. A., 1994. Communities of epibiota on two erect species of Antarctic Bryozoa. Journal of Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 74: 863–872.

Barrett, P. J., 1999. Antarctic climate history over the last 100 million years. Terra Antarctica 3: 53–72.

Barroso, R., M. Klautau, A. M. Sole-Cava & P. C. Paiva, 2010. Eurythoe complanata (Polychaeta: Amphinomidae), the “cosmopolitan” fireworm, consists of at least three cryptic species. Marine Biology 157: 69–80.

Bhaud, M., 1998. The spreading potential of polychaete larvae does not predict adult distributions; consequences for conditions of recruitment. Hydrobiologia 375(376): 35–47.

Bleidorn, C., I. Kruse, S. Albrecht & T. Bartolomaeus, 2006. Mitochondrial sequence data expose the putative cosmopolitan polychaete Scoloplos armiger (Annelida, Orbiniidae) as a species complex. BMC Evolutionary Biology 6: 47.

Błażewicz-Paszkowycz, M. & J. Sekulska-Nalewajko, 2004. A comparison of tanaid fauna of two polar fjords: Kongsfjorden, Spitsbergen (Arctic) and Admiralty Bay, King George Island (Antarctic). Polar Biology 27: 222–230.

Brandt, A., 1997. Abundance, diversity and community patterns of epibenthic- and benthic-boundary layer peracarid crustaceans at 75 N off East Greenland. Polar Biology 17: 159–174.

Brandt, A., 2001. Great differences in peracarid crustacean density between the Arctic and Antarctic deep sea. Polar Biology 24: 785–789.

Brandt, A., M. Błażewicz-Paszkowycz, R. N. Bamber, U. Muhlenhardt-Siegel, M. V. Malyutina, S. Kaiser, C. DeBroyer & C. Hevermans, 2012. Are there peracarid species in the deep sea (Crustacea: Malacostraca)? Polis Polar Research 33: 139–162.

Campos, L. S., C. A. M. Barboza, M. Bassoi, M. Bernardes, S. Bromberg, T. N. Corbisier, R. F. C. Fontes, P. F. Gheller, E. Hajdu, H. G. Kawall, P. K., Lange, A. M. Lanna, H. P. Lavrado, G. C. S. Monteiro, R. C. Montone, T. Morales, R. B. Moura, C. R. Nakayama, T. Oackes, R. Paranhos, F. D. Passos, M. A. V. Petti, V. H. Pellizari, C. E. Rezende, M. Rodrigues, L. H. Rosa, E. Secchi, D. Tenenbaum & Y. Yoneshigue-Valentin, 2013. Environmental Processes, Biodiversity and Changes in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica Adaptation and Evolution in Marine Environments, Vol. 2 From Pole to Pole: 127–156.

Carr, C. M., 2012. Polychaete diversity and distribution patterns in Canadian marine waters. Marine Biodiveristy 42: 93–107.

Clarke, A. & J. A. Crame, 2010. Evolutionary dynamics at high latitudes: speciation and extinction in polar marine faunas. Phylosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 365: 3655–3666.

Colwell, R. K., 2009. EstimateS: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples, Version 8.2. User’s guide and application published at [http://purl.oclc.org/estimates].

Cornell, H. V. & J. H. Lawton, 1992. Species interactions, local and regional processes, and limits to the richness of ecological communities: a theoretical perspective. Journal of Animal Ecology 61: 1–12.

Crame, J. A., 1997. An evolutionary framework for the polar regions. Journal of Biogeography 24: 1–9.

Dayton, P. K., 1990. Polar benthos. In Smith, W. (ed.), Polar Oceanography. Academic Press, London: 631–685.

Dayton, P. K., B. J. Mordida & F. Bacon, 1994. Polar marine communities. American Zoologist 34: 90–99.

De Broyer, C., B. Danis, L. Allcock, M. Angel, C. Arango, T. Artois, D. Barnes, I. Bartsch, M. Bester, K. Błachowiak-Samołyk, M. Błażewicz, J. Bohn, A. Brandt, S. N. Brandao, B. David, M. de Salas, M. Eleaume, C. Emig, D. Fautin, K. H. George, D. Gillan, A. Gooday, R. Hopcroft, M. Jangoux, D. Janussen, P. Koubbi, J. Kouwenberg, P. Kuklinski, R. Ligowski, D. Lindsay, K. Linse, M. Longshaw, P. Lopez-Gonzalez, P. Martin, T. Munilla, U. Muhlenhardt-Siegel, B. Neuhaus, J. Norenburg, C. Ozouf-Costaz, E. Pakhomov, W. Perrin, V. Petryashov, A. L. Pena-Cantero, U. Piatkowski, A. Pierrot-Bults, A. Rocka, J. Saiz-Salinas, L. Salvini-Plawen, V. Scarabino, S. Schiaparelli, M. Schrodl, E. Schwabe, F. Scott, J. Siciński, V. Siegel, I. Smirnov, S. Thatje, A. Utevsky, A. Vanreusel, C. Wiencke, E. Woehler, K. Zdzitowiecki & W. Zeidler, 2011. How many species in the Southern Ocean? Towards a dynamic inventory of the Antarctic marine species. Deep-Sea Research Part II – Topical Studies in Oceanography 58: 5–17.

Eilertsen, H. C., J. P. Taasen & J. M. Wesławski, 1989. Phytoplankton studies in the fjords of West Spitsbergen. Physical environment, production in spring and summer. Journal of Plankton Research 11: 1245–1260.

Ellingsen, K. E., J. E. Hewitt & S. F. Thrush, 2007. Rare species, habitat diversity and functional redundancy in marine benthos. Journal of Sea Research 58: 291–301.

Fauchald, K. & P. A. Jumars, 1979. The diet of worms: a study of polychaete feeding guilds. Oceanography and Marine Biology - An Annual Review 17: 193–284.

Fontana, G., K. I. Ugland, J. S. Gray, T. J. Willis & M. Abbiati, 2008. Influence of rare species on beta diversity estimates in marine benthic assemblages. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 366: 104–108.

Gallardo, V. A., S. A. Medrano & F. D. Carrasco, 1988. Taxonomic composition of the sublittoral soft-bottom Polychaeta of Chile Bay (Greenwich Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica). Ser Cient INACH 37: 49–67.

Giangrande, A., M. Licciano & L. Musco, 2005. Polychaetes as environmental indicators revised. Marine Pollution Bulletin 50: 1153–1162.

Grange, L. J. & C. R. Smith, 2013. Megafaunal communities in rapidly warming fjords along the West Antarctic Peninsula: hotspots of abundance and beta diversity. Plos One 8: e77917.

Gray, J. S., 2000. The measurement of Marine species diversity, with an application to the benthic fauna of the Norwegian Continental shelf. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 250: 23–49.

Grebmeier, J. M., 2012. Shifting patterns of life in the pacific Arctic and sub-Arctic seas. Annual Review of Marine Science 4: 63–78.

Gordon, A. L. & W. D. J. Nowlin, 1978. The basin waters of the Bransfield Strait. Journal of Physical Oceanography 8: 258–264.

Gorlich, K., J. M. Wesławski & M. Zajaczkowski, 1987. Suspension settling effect on macrobenthos biomass distribution in the Hornsund fjord, Spitsbergen. Polar Research 5: 175–192.

Gutt, J. & D. Piepenburg, 2003. Scale-dependent impact on diversity of Antarctic benthos caused by grounding of icebergs. Marine Ecology Progress Series 253: 77–83.

Gutt, J. & T. Schickan, 1998. Epibiotic relationships in the Antarctic benthos. Antarctic Science 10: 398–405.

Hartman, O., 1964. Polychaeta Errantia of Antarctica. Antarctic Research Series 3: 1–131.

Hartman, O., 1966. Polychaeta, Myzostomidae and Sedentaria of Antarctica. Antarctic Research Series 7: 1–143.

Hartman, O., 1967. Polychaetous annelids collected by the USNS Eltanin and Staten Island cruises, from Antarctic Seas. Allan Hancock Monographs in Marine Biology. Number 2, Los Angeles.

Hartmann-Schroder, G., 1986. Die Polychaeten der 56 Reise der “Meteor” zu den South Shetland-Inseln (Antarktis) Mitteilungen aus dem Hamburgischen Zoologischen Museum und Institut 83: 71–100.

Hartmann-Schroder, G. & P. Rosenfleldt, 1988. Die Polychaeten der “Polarstern” – Reise ANT III/2 in die Antarktis 1984, Teil 1: Euphrosinidae bis Chaetopteridae. Mitteilungen aus dem Hamburgischen Zoologischen Museum und Institut 85: 25–72.

Hartmann-Schroder, G. & P. Rosenfleldt, 1989. Die Polychaeten der “Polarstern” – Reise ANTIII/2 in die Antarktis 1984. Teil 2: Cirratulidae bis Serpulidae). Mitteilungen aus dem Hamburgischen Zoologischen Museum und Institut 86: 65–106.

Havermans, C., G. Sonet, C. d’Udekem d’Acoz, Z. T. Nagy, P. Martin, S. Brix, T. Riehl, S. Agrawal & C. Held, 2013. Genetic and morphological divergences in the cosmopolitan deep-sea amphipod Eurythenes gryllus reveal a diverse abyss and bipolar species. PlosOne 8: e74218.

Hillebrandt, H. & T. Blenckner, 2002. Regional and local impact on species diversity – from pattern to processes. Oecologia 132: 479–491.

Hurlbert, S. H., 1971. The non-concept of species diversity: a critique and alternative parameters. Ecology 52: 577–586.

Hutchings, P. A., T. J. Ward, J. H. Waterhouse & L. Walker, 1993. Infauna of marine sediments and seagrass beds of Upper Spence Gulf near Port Pirie, South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 117: 1–15.

Jażdżewski, K., J. M. Węsławski & C. De Broyer, 1995. A comparison of the amphipod faunal diversity in two polar fjords: Admiralty Bay, King George Island (Antarctic) and Hornsund, Spitsbergen (Arctic). Polish Archives of Hydrobiology 42: 367–384.

Kędra, M., S. Gromisz, R. Jaskuła, J. Legeżyńska, B. Maciejewska, E. Malec, A. Opanowski, K. Ostrowska, M. Włodarska-Kowalczuk & J. M. Węsławski, 2010a. Soft bottom macrofauna of an All Taxa biodiversity site: Hornsund (77°N, Svalbard). Polish Polar Research 31: 309–326.

Kędra, M., M. Włodarska-Kowalczuk & J. M. Węsławski, 2010b. Decadal change in soft-bottom community structure in high arctic fjord (Kongsfjorden, Svalbard). Polar Biology 33: 1–11.

Kędra, M., K. Pabis, S. Gromisz & J. M. Węsławski, 2013. Distribution patterns of polychaete fauna in an Arctic fjord (Hornsund, Spitsbergen). Polar Biology 36: 1463–1472.

Kendall, M. A., S. Widdicombe & J. M. Węsławski, 2003. A multi-scale study of the biodiversity of the benthic infauna of the high-latitute Kongsfjord, Svalbard. Polar Biology 26: 383–388.

Knox, G. A., 1977. The role of polychaetes in benthic soft-bottom communities In Reich, D. J., & K. Fauchald (eds), Essays on Polychaetes Annelids in Memory of Dr Olga Hartman. Allan Hancock Fundation, Los Angeles: 526–546.

Knox, G. A. & J. K. Lowry, 1977. A comparison between the benthos of the Southern Ocean and the North Polar Ocean with special reference to the Amphipoda and the Polychaeta. In Dunbar, M. J. (ed.), Polar Oceans. Arctic Institute of North America, Calgary: 423–462.

Lipski, M., 1987. Variations of physical conditions, nutrients and chlorophyll a contents in Admiralty Bay (King George Island, South Shetland Islands, 1979). Polish Polar Research 8: 307–332.

Lovell, L. L. & K. D. Trego, 2003. The epibenthic megafaunal and benthic infaunal invertebrates of Port Foster, Deception Island (South Shetland Islands, Antarctica). Deep-Sea Research II 50: 1799–1819.

Mackie, A. S. Y. & G. Oliver, 1993. The macrobenthic infauna of Hoi Ha Wan and Tolo Chanel, Hong Kong. In Morton, E. (ed.), Proceedings of the 1st International Marine Biology Workshop: The Marine Flora and Fauna of Hong Kong and Southern China. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong: 657–674.

Magurran, A. E., 2004. Measuring Biological Diversity. Blackwell Publishing, Carlton.

Marsz, A., 1983. From surveys of the geomorphology of the shores and bottom of the Ezcurra Inlet. Oceanologia 15: 209–220.

Olsgard, F. & P. J. Somerfield, 2000. Surrogates in marine benthic investigations – which taxonomic unit to target? Journal of Aquatic Ecosystem Stress and Recovery 7: 25–42.

Olsgard, F., T. Brattegard & T. Holthe, 2003. Polychaetes as surrogates for marine biodiversity: lower taxonomic resolution and indicator groups. Biodiversity and Conservation 12: 1033–1049.

Orensanz, J. M., 1990. The eunicemorph polychaete annelids from Antarctic and Subanantarctic seas. Antarctic Research Series 52: 1–183.

Pęcherzewski, K., 1980. Distribution and quantity of suspended matter in Admiralty Bay (King George Island, South Shetland Islands. Polish Polar Research 1: 75–82.

Pabis, K. & J. Siciński, 2010. Distribution and diversity of polychaetes collected by trawling in Admiralty Bay – an Antarctic glacial fiord. Polar Biology 33: 141–151.

Pabis, K., J. Siciński & M. Krymarys, 2011. Distribution patterns in the biomass of macrozoobenthic communities in Admiralty Bay (King George Island, South Shetlands, Antarctic). Polar Biology 34: 489–500.

Pabis, K., M. Błażewicz-Paszkowycz, P. Jóźwiak & D. K. A. Barnes, 2014. Tanaidacea of the Amundsen and Scotia seas: an unexplored diversity. Antarctic Science. doi:10.1017/S0954102014000303.

Pagliosa, P. R., 2005. Another diet of worms: the applicability of polychaete feeding guilds as a useful conceptual framework and biological variable. Marine Ecology 26: 246–254.

Palerud, R., B. Gulliksen, T. Brattegard, J. A. Sneli & W. Vader, 2004. The marine macro-organisms in Svalbard waters. In Prestrud, P. (ed.), A Catalogue of the Terrestrial and Marine Animals of Svalbard. Norwegian Polar Institute, Tromsø: 5–56.

Parapar, J. & G. San Martin, 1997. “Sedentary” polychaetes of the Livingston Island shelf (South Shetlands, Antarctica), with the description of a new species. Polar Biology 17: 502–514.

Parapar, J. & J. Moreira, 2008. Redescription of Terebellides kerguelensis stat. nov. (Polychaeta: Trichobranchidae) from Antarctic and subantarctic waters. Helgoland Marine Research 62: 143–152.

Piepenburg, D., 2005. Recent research on Arctic benthos: common notions need to be revisited. Polar Biology 28: 733–755.

Piepenburg, D., J. Voß & J. Gutt, 1997. Assemblages of sea stars (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) and brittle stars (Echinoder- mata: Ophiuroidea) in the Weddell Sea (Antarctica) and off Northeast Greenland (Arctic): a comparison of diversity and abundance. Polar Biology 17: 305–322.

Piepenburg, D., P. Archambault, W. G. Ambrose Jr, A. Blanchard, B. Bluhm, C. L. Carroll, K. E. Conlan, M. Cusson, H. M. Feder, J. M. Grebmeier, S. C. Jewett, M. Levesque, V. V. Petryashev, M. K. Sejr, B. I. Sirenko & M. Włodarska-Kowalczuk, 2011. Towards a pan-Arctic inventory of the species diversity of the macro- and megabenthic fauna of the Arctic shelf seas. Marine Biodiveristy 41: 51–70.

Piwosz, K., W. Walkusz, R. Hapter, P. Wieczorek, H. Hop & J. Wiktor, 2009. Comparison of productivity and phytoplankton in a warm (Kongsfjorden) and a cold (Hornsund) Spitsbergen fjord in midsummer 2002. Polar Biology 32: 549–559.

Rakusa-Suszczewski, S., 1993. The Maritime Antarctic Coastal Ecosystem of Admiralty Bay. Department of Antarctic Biology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw.

Ricklefs, R. E., 2000. The relationship between local and regional species in birds of the Caribbena Basin. Journal of Animal Ecology 69: 1111–1116.

Rouse, G. & F. Pleijel, 2001. Polychaetes. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Rudowski, S. & A. A. Marsz, 1996. Cechy rzeźby dna i pokrywy osadowe we współcześnie kształtujących się fiordach na przykładzie Hornsundu (Spitsbergen) oraz Zatoki Admiralicji (Antarktyka Zachodnia). Prace Wydziału Nawigacyjnego Wyższej Szkoły Morskiej w Gdyni 3: 39–81.

Salas, F., J. M. Neto, A. Borja & J. C. Marques, 2004. Evaluation of the applicability of marine biotic index to characterize the status of estuarine ecosystems: the case of Mondego estuary (Portugal). Ecological Indicators 4: 215–225.

San Martin, G. & J. Parapar, 1997. “Errant” polychaetes of the Livingston Island shelf (South Shetlands, Antarctica), with the description of a new species. Polar Biology 17: 285–295.

San Martin, G., J. Parapar, F. J. Garcia & M. S. Redondo, 2000. Quantitative analysis of soft bottoms infaunal macrobenthic polychaetes from South Shetland Islands (Antarctica). Bulletin of Marine Science 67: 83–102.

Scaps, P., A. Rouabah & A. Lepretre, 2000. Morphological and biochemical evidence that Perinereis cultifera (Polychaeta: Nereididae) is a complex of species. Journal of Marine Association of the United Kingdom 80: 735–736.

Siciński, J., 1986. Benthic assemblages of Polychaeta in chosen regions of the Admiralty Bay (King George Island, South Shetland Islands). Polish Polar Research 7: 63–78.

Siciński, J., 2004. Polychaetes of Antarctic sublittoral in the proglacial zone (King George Island, South Shetland Islands). Polish Polar Research 25: 67–96.

Siciński, J., K. Jażdżewski, C. De Broyer, P. Presler, R. Ligowski, E. F. Nonato, T. N. Corbisier, M. A. V. Petti, T. A. S. Brito, H. P. Lavrado, M. Błażewicz-Paszkowycz, K. Pabis, A. Jażdżewska & L. S. Campos, 2011. Admiralty Bay Benthos diversity - a census of a complex polar ecosystem. Deep-Sea Res Part II 58: 30–48.

Siciński, J., K. Pabis, K. Jażdżewski, A. Konopacka & M. Blazewicz-Paszkowycz, 2012. Macrozoobenthos of two Antarctic glacial coves: a comparison with non-disturbed bottom areas. Polar Biology 35: 355–367.

Sirenko, B. I., 2001. List of Species of Free-Living Invertebrates of Eurasian Arctic Seas and Adjacent Deep Waters. Russian Academy of Sciences, Zoological Institute, St Petersburg.

Sirenko, B. I., 2009. Main differences in macrobenthos and benthic communities of the Arctic and Antarctic, as illustrated by comparison of the Laptev and Weddell Sea faunas. Russian Journal of Marine Biology 35: 445–453.

Smale, D. A. & D. K. A. Barnes, 2008. Likely response of the Antarctic benthos to climate-related changes in physical disturbance during the 21st century, based primarily on evidence from the West Antarctic Peninsula region. Ecography 31: 289–305.

Smith, S. D. A., 2000. Evaluating stress in rocky shore and shallow reef habitats using the macrofauna of kelp holdfasts. Journal of Aquatic Ecosystem Stress and Recovery 7: 259–272.

Starmans, A. & J. Gutt, 2002. Mega-epibenthic diversity: a polar comparison. Marine Ecology Progress Series 225: 45–52.

Starmans, A., J. Gutt & W. E. Arntz, 1999. Mega-epibenthic communities in Arctic and Antarctic shelf areas. Marine Biology 135: 269–280.

Swerpel, S., 1985. The Hornsund fiord: water masses. Polish Polar Research 4: 475–496.

Tokarczyk, R., 1986. Annual cycle of chlorophyll α in Admiralty Bay 1981–1982 (King George Island, South Shetland). Polish Archives of Hydrobiology 3: 177–188.

Tokarczyk, R., 1987. Classification of water masses in the Bransfield Strait and southern part of the Drake Passage using a method of statistical multidimensional analysis. Polish Polar Research 8: 333–366.

Urbański, J., E. Neugebauer, R. Spacjer & L. Falkowska, 1980. Physico chemical characteristics of the waters of Hornsund fjord on South West Spitsbergen. Polish Polar Research 1: 43–52.

Voronkov, A., H. Hop & B. Gulliksen, 2013. Diversity of hard-bottom fauna relative to environmental gradients in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Polar Research 32: 11208.

Walsh, J. E., 2009. A comparison of Arctic and Antarctic climate change, present and future. Antarctic Science 21: 179–188.

Warwick, R. M., C. S. Emblow, J. P. Feral, H. Hummel, P. van Avesaath & C. Heip, 2003. European 520 marine biodiversity research sites. Report of the European Concerted Action: BIOMARE. NIOO521 CEME, Yerseke.

Węsławski, J. M., J. Koszteyn, M. Zajączkowski, J. Wiktor & S. Kwaśniewski, 1995. Fresh water in Svalbard fjord ecosystems. In Hopkins, C. C., K. E. Erikstad & H. P. Leinaas (eds), Ecology of Fjord and Coastal Watered. Elsevier, Amsterdam: 229–241.

Węsławski, J. M., M. A. Kendall, M. Włodarska-Kowalczuk, K. Iken, M. Kędra, J. Legeżyńska & M. K. Sejr, 2011. Climate change effects on Arctic fjord and coastal macrobenthic diversity—observations and predictions. Marine Biodiversity 41: 71–85.

Witman, J. D., R. J. Etter & F. Smith, 2004. The relationship between regional and local species diversity in marine benthic communities: a global perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101: 15664–15669.

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M. & T. Pearson, 2004. Soft-bottom macrobenthic faunal associations and factors affecting species distributions in an Arctic glacial fjord (Kongsfjord, Spitsbergen). Polar Biology 27: 155–167.

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M. & M. Kędra, 2007. Surrogacy in natural patterns of benthic distribution and diversity: Selected taxa versus lower taxonomic resolution. Marine Ecology Progress Series 351: 53–63.

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M., J. Siciński, S. Gromisz, M. A. Kendall & S. Dahle, 2007. Similar soft-bottom polychaete diversity in Arctic and Antarctic marine inlets. Marine Biology 151: 607–616.

Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M., P. E. Renaud, J. M. Węsławski, S. K. J. Cochrane & S. G. Denisenko, 2012. Species diversity, functional complexity and rabity in Arctic fjords versus open shelf benthic systems. Marine Ecology Progress Series 463: 73–87.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an International Polar Year related project (Structure, evolution, and dynamics of lithosphere, cryosphere and biosphere in European Sector of Arctic and in Antarctic No. PBZ-KBN-108/PO4/2004) to Jan Marcin Węsławski and Jacek Siciński. K. Pabis was also partially supported from the University of Lodz internal funds, M. Kędra received financial support from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (540/N–AODP/2009/0). Many thanks to captains and crews of r/v Oceania and m/v Polar Pioneer. We also want to thank Witold Szczuciński from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan and Georg Schettler from Geo Forschungs-Zentrum in Potsdam for providing their unpublished data and Katarzyna Huzarska for help with sediments analysis. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for all comments and suggestions that helped us to improve this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling editor: Vasilis Valavanis

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pabis, K., Kędra, M. & Gromisz, S. Distinct or similar? Soft bottom polychaete diversity in Arctic and Antarctic glacial fjords. Hydrobiologia 742, 279–294 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-014-1991-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-014-1991-5