Abstract

Extant felids are hyper-carnivorous predators that originated in Asia c. 11 Mya and diversified in 8 distinct lineages, with 41 species surviving to the Recent. These species occupy almost every terrestrial habitat available in the four continental land masses they occupy and exhibit morphological and behavioral specializations to various locomotor styles and hunting modes. Today, distinct felid ensembles inhabit each continent and major biogeographic region. How the differential structuring of these ensembles was generated, and which evolutionary processes shaped these differences across ensembles, are key emerging questions. Using multivariate statistics, we analyzed a large dataset of 31 cranial and 92 postcranial linear variables describing shape and functional proxies of the entire skeleton of extant felids. We statistically demonstrate the existence of nine felid morphotypes at the global scale, whose occurrence is characteristic of different continental or biogeographic ensembles. Phylogenetically explicit analyses show that morphotypes from different felid lineages converged in different continents, but still ensembles remain distinct due to the fact that various morphotypes are missing in several of those ensembles. However, fossil evidence suggests that most of these missing morphotypes were represented by species from those territories that went extinct during the Quaternary. Furthermore, reconstructing the hypothetical felid ensembles before Pleistocene extinctions rendered the continental felid faunas remarkably more similar to each other than they presently are, leaving their remaining, relatively minor differences to outstanding geographic singularities of each continental land mass.

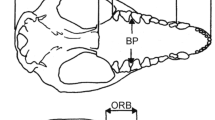

modified from Johnson et al. (2006) by adding newly recognized species following Kitchener et al. (2017). Dashed lines in the cladogram represent changes from the tree of Johnson et al. (2006). Species colors: blue, Paleartic; red, AF + SWAS; green, Neotropics; violet, Oriental; light blue, Neartic; black, more than one region. Vertical dashed lines, estimated dates for trans-continental migrations; Red dots, trans-continental migrations suggested by Johnson et al. (2006). UN-, untransformed data; SC, size corrected data. *Species with no postcranial data available; + , species with no combined data available. Numbers in clades represent partitions used for CPO analyses. Arrows represent retained partitions after stepwise selection (P value < 0.01). a 8.5–8.0 my migration from Eurasia to North America; b 6.7–6.2 my migration from North America to Asia; c 2.7 my, migration from North America to South America; d 2.7 my migration from Asia to Africa and Americas (data from Johnson et al. 2006)

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability and material

Data deposited in the Mendeley repository: https://doi.org/10.17632/fntx8pt8fv.1. Specimens used are stored in the Institutions declared in Material and Methods section.

References

Adams DC (2014) A method for assessing phylogenetic least squares models for shape and other high-dimensional multivariate data. Evolution 68:2675–2688

Adams D, Collyer M, Kaliontzopoulou A (2020) Geomorph: Software for geometric morphometric analyses. R package version 3.3.1. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/package=geomorph (accessed November 2020)

Bacon CD, Molnar P, Antonelli A et al (2016) Quaternary glaciation and the Great American Biotic Interchange. Geology 44:375–378

Barnett R, Barnes I, Phillips MJ et al (2005) Evolution of the extinct sabertooths and the American cheetah-like cat. Curr Biol 15:589–590

Barnett R, Yamaguchi N, Barnes I et al (2006) The origin, current diversity, and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo). Proc R Soc B 273:2159–2168

Barnett R, Shapiro B, Barnes I et al (2009) Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity. Molec Ecol 18:1668–1677

Barnett R, Zepeda Mendoza ML, Rodrigues Soares AE et al (2016) Mitogenomics of the extinct cave lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), resolve its position within the Panthera cats. Open Quatern 2:p4

Baryshnikov G, Boeskorov G (2001) The Pleistocene cave lion Panthera spelaea (Carnivora, Felidae) from Yakutia, Russia. Cranium 18:7–24

Behling H, Bush M, Hooghiemstra H (2010) Biotic development of quaternary amazonia: a palynological perspective. In: Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP (eds) Amazonia: landscape and species evolution: a look into the past. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Chichester, pp 335–345

Biggins DE, Hanebury LR, Miller BJ et al (2011) Black-footed ferrets and Siberian polecats as ecological surrogates and ecological equivalents. J Mammal 92:710–720

Buckley-Beason VA, Johnson WE, Nash WG et al (2006) Molecular evidence for species-level distinctions in clouded leopards. Curr Biol 16:2371–2376

Burger J, Rosendahl W, Loreille O et al (2004) Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea. Mol Phylogenetics Evol 30:841–849

Carbonell E, Rodríguez XP (2000) El Pleistoceno inferior de la Península Ibérica. SPAL Rev Prehist Arqueol Univ Sevilla 9:31–47

Carrillo JD, Forasiepi A, Jaramillo C et al (2015) Neotropical mammal diversity and the Great American Biotic Interchange: spatial and temporal variation in South America’s fossil record. Front Genet 5:451

Cherin M, Iurino DA, Sardella R (2013) Earliest occurrence of Puma pardoides (Owen, 1846) (Carnivora, Felidae) at the Plio/Pleistocene transition in western Europe: New evidence from the Middle Villafranchian assemblage of Montopoli, Italy. CR Palevol 12:165–171

Christiansen P (2007) Comparative bite forces and canine bending strength in feline and sabertooth felids: implications for predatory ecology. Zool J Linn Soc 151:423–437

Christiansen P (2008) Evolution of skull and mandible shape in cats (Carnivora: Felidae). PLoS ONE 3:e2807

Christiansen P, Mazák JH (2008) A primitive Late Pliocene cheetah, and the evolution of the cheetah lineage. PNAS 106:512–515

Clarke KR (1993) Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Austral Ecol 18:117–143

Dayan T, Simberloff D (2005) Ecological and community-wide character displacement: the next generation. Ecol Letters 8:875–894

Dayan T, Simberloff D, Tchernov E et al (1990) Feline canines: community-wide character displacement among the small cats of Israel. Am Nat 136:39–60

Driscoll CA, Menotti-Raymond M, Roca AL et al (2007) The Near Eastern origin of cat domestication. Science 317:519

Fauth JE, Bernardo J, Camara M et al (1996) Simplifying the jargon of community ecology: a conceptual approach. Am Nat 147:282–286

Freudenberg W (1910) Die Saügetierfauna des Pliocäns und Postpliocäns von Mexiko. 1. Carnivoren Geol Paläont Abh 8:193–231

Geigl EM, Grange T (2018) Of cats and men: ancient DNA reveals how the cat conquered the ancient world. In: Lindqvist C, Rajora O (eds) Paleogenomics. Population genomics. Springer, Cham, pp 307–324

Geraads D (1980) Un nouveau felide (Fissipeda, Mammalia) du Pleistocene moyen du Maroc: Lynx thomasi n. sp. Géobios 13:441–444

Giannini NP (2003) Canonical phylogenetic ordination. Syst Biol 52:684–695

Gonyea WJ (1976) Adaptive differences in the body proportions of large felids. Acta Anat 96:81–96

Grafen A (1989) The phylogenetic regression. Phil Trans Royal Soc B 326:119–157

Haas SK, Hayssen V, Krausman PR (2005) Panthera leo. Mammalian Species 762:1–11

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD (2001) PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron 4:1–9

Hemmer H, Kahlke RD, Vekua AK (2010) Panthera onca georgica ssp. nov. from the early pleistocene of dmanisi (Republic of Georgia) and the phylogeography of jaguars (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae). N Jb Geol Paläont Abh 257:115–127

Johnson WE, Dratch PA, Martenson JS et al (2006) The late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: a genetic assessment. Science 311:73–77

Kiltie RA (1984) Size ratios among sympatric neotropical cats. Oecologia 61:411–416

Kitchener AC, Breitenmoser-Würsten C, Eizirik E et al (2017) A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: the final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group. Cat News Special Issue 11:80

Koch PK, Barnosky AD (2006) Late quaternary extinctions: state of the debate. Annual Rev Ecol Evol Syst 37:215–250

Kreft H, Jetz W (2010) A framework for delineating biogeographical regions based on species distributions. J Biogeogr 37:2029–2053

Kurtén B (1965) The pleistocene felidae of Florida. Bull Florida State Mus 9:215–273

Kurtén B (1968) Pleistocene mammals of Europe. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, pp 88–90

Kurtén B (1985) The pleistocene lion of Beringia. Ann Zool Fenn 22:117–121

Kurtén B, Anderson E (1980) Pliocene cats of North America. Columbia University Press, Nueva York

Lemon RR, Churcher CS (1961) Pleistocene geology and paleontology of the Talara region, northwest Peru. Am J Sci 259:410–429

Lewis ME, Lague MR (2010) Interpreting sabertooth cat (Carnivora; Felidae; Machairodontinae†) postcranial morphology in light of scaling patterns in felids. In: Goswami A, Friscia A (eds) Carnivoran evolution: new views on phylogeny, form and function. Cambridge University Press, Nueva York, pp 411–465

Madurell-Malapeira J, Alba DM, Moyà-Solà S et al (2010) The Iberian record of the puma-like cat Puma pardoides (Owen, 1846) (Carnivora, Felidae). CR Palevol 9:55–62

Meachen-Samuels J, Van Valkenburgh B (2009a) Craniodental indicators of prey size preference in the Felidae. Biol J Linn Soc 96:784–799

Meachen-Samuels J, Van Valkenburgh B (2009b) Forelimb indicators of prey-size preference in the Felidae. J Morphol 270:729–744

Montellano-Ballesteros M, Carbot-Chanona G (2009) Panthera leo atrox (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Chiapas, Mexico. Southwest Nat 54:217–222

Morales M (2012) Morfología funcional en los ensambles de félidos: efectos biogeográficos continentales, filogenéticos, y de las extinciones pleistocenas. Dissertation, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán

Morales M, Giannini NP (2010) Morphofunctional patterns in Neotropical felids: species coexistence and historical assembly. Biol J Linn Soc 100:711–724

Morales M, Giannini NP (2013a) Pleistocene extinctions and the perceived morphofunctional structure of the Neotropical felid ensemble. J Mammal Evol 21:395–405

Morales M, Giannini NP (2013b) Ecomorphology of the African felid ensemble: the role of the skull and postcranium in determining species segregation and assembling history. J Evol Biol 26:980–992

Morgan GS, Seymour KL (1997) Fossil history of puma and cheetah-like cat in Florida. Bull Florida Mus Nat His 40:177–219

Price MF, Byers AC, Friend DA et al (eds) (2013) Mountain geography: physical and human dimensions. University of California Press, California

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available from https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed November 2020

Ray CE (1964) The Jaguarundi in the Quaternary of Florida. J Mammal 45(330):332

Ricklefs RE (1998) Invitación a la Ecología, la economía de la Naturaleza, 4th edn. Editorial Médica Panamericana, Buenos Aires

Seymour K (2015) Perusing Talara: overview of the late pleistocene fossils from the tar seeps of Peru. Nat His Mus LA County Sci Ser 42:97–109

Sicuro FL, Oliveira LFB (2010) Skull morphology and functionality of extant Felidae (Mammalia: Carnivora): a phylogenetic and evolutionary perspective. Zool J Linn Soc 161:414–462

Simpson GG (1941) Large Pleistocene felines of North America. Am Mus Nov 1136:1–27

Stayton CT (2015) The definition, recognition, and interpretation of convergent evolution, and two new measures for quantifying and assessing the significance of convergence. Evolution 69:2140–2153

Stayton CT (2018) convevol: analysis of convergent evolution. R package version 1.3. Available from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=convevol

Stokstad E (2009) On the origin of ecological structure. Science 326:33–35

Sunquist ME, Sunquist FC (2002) Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Sunquist ME, Sunquist FC (2009) Family felidae. In: Wilson DE, Mittermeir RA (eds) Handbook of mammals of the world, vol 1. Carnivores. Lynx editions, Barcelona, pp 54–168

Tellaeche CG, Reppucci JI, Morales M et al (2018) External and skull morphology of the Andean cat and Pampas cat: new data from the high Andes of Argentina. J Mammal 99:906–914

ter Braak CJF (1995) Ordination. In: Jongman RHG, ter Braak CJF, van Tongeren OFR (eds) Data analysis in community and landscape ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 91–173

Turner A, Antón M (1997) The big cats and their fossil relatives. Columbia University Press, New York

UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre (2002) Mountain watch: environmental change and sustainable development in mountains. UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK

Werdelin L (1985) Small pleistocene felines of North America. J Verteb Paleontol 5:194–210

Werdelin L, Yamaguchi N, Johnson WE et al (2010) Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae). In: Macdonald DW, Loveridge AJ (eds) Biology and conservation of wild felids. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 59–88

Yamaguchi N, Cooper A, Werdelin L et al (2004) Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review. J Zool 263:329–342

Zhanxiang Q (2003) Dispersals of Neogene Carnivorans between Asia and North America. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist 279:18–31

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge all curators and personal involved in all collections visited (institutions in alphabetical order): Nancy Simmons, Eileen Westwig, Eleanor Hoeger, Brian O'Toole (AMNH); Ned Gilmore (ANSP); Ulyses Pardiñas (CNP); James Aparicio, Julieta Tordoya (CBF); Martín Monteverde (APN); Ricardo Ojeda (CMI); Mauro Lucherini, Estela Luengos Vidal (CGECM); Rubén Barquez, Mónica Díaz (CML); Marcelo Carrera (MC); Daniel Hernández (ZVC-M); Lawrence Heaney, William Stanley (FMNH); David Flores, Valentina Segura, Pablo Teta, Sergio Lucero (MACN); Pablo Perovic, Jorge Samaniego (MCN-UNSa); Víctor Pacheco, Carlos Tello (MUSM); Diego Verzi, Itatí Olivares, Cecilia Morgan (MLP); Damián Romero, Alejandro Dondas, Fernando Scaglia (MMPMa); Enrique González, Yennifer Hernández, José González (MNHN); Norka Rocha (MNK); Don Wilson, Darrin Lunde, Kristofer Helgen, John Ososky; Alfred Gardner, Linda Gordon, Jeremy Jacobs (USNM). Thanks to Per Ericson, Olavi Grönwall and Francisco Prevosti for facilitating photographic records of specimens of the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm and National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo respectively. MMM acknowledge Virginia Abdala and Sergio Vizcaíno for their support along her thesis. We thank Lars Werdelin for improving an earlier version of the manuscript and Jessica Fratani for her help in statistical analysis. Thanks to the reviewers and editor for their extremely constructive suggestions. This work was partially supported by CONICET, a Short-Term Visitor Fellowship granted by Smithsonian Institution and a Roosevelt Memorial Award granted by the American Museum of Natural History to MMM. We thank PICT 2015-0708 to MMM and PICT 2015-2389 and PICT 2016-3682 to NPG.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, a Short-Term Visitor Fellowship granted by Smithsonian Institution and a Roosevelt Memorial Award granted by the American Museum of Natural History to MMM. We thank Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación, Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (PICT 2015-0708; PICT 2015-2389 and PICT 2016-3682).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMM and NPG conceived the ideas and designed methodology and contributed to the shaping and production of the manuscript. MMM measured all specimens, carried out the statistical analysis and prepared figures, tables and Supplementary Information. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Confict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Consent to participate and for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morales, M.M., Giannini, N.P. Pleistocene extinction and geographic singularity explain differences in global felid ensemble structure. Evol Ecol 35, 271–289 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-021-10103-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-021-10103-2