Abstract

The sharing economy is established as a new economy in the digital era. Many reviews on the sharing economy avail, but none, to date, has shed enough light to illuminate understanding pertaining to the similar and dissimilar characteristics of consumers and producers in the sharing economy. To address this gap, this paper aims to provide a one-stop, state-of-the-art overview of existing research on the sharing economy through the lens of consumers and producers. To do so, this paper conducts a systematic review of 148 articles on the sharing economy identified through the snowballing technique and organized using the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes (ADO) and theories, contexts, and methods (TCM) frameworks. In doing so, this paper unpacks the trust, personal, economic, social, entrepreneurial, environmental, legal, and technological factors that impact on behavioural performance, loyalty, and impact factors among consumers and producers in the sharing economy. Finally, this paper also reveals the theories, contexts, and methods that avail for sharing economy research, as well as the potentially fruitful directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 History of the sharing economy

With the evolution in the mindset of the society, the ideology of ownership has begun to diminish among the younger generation [31]. The need to own assets has become secondary as the younger generation look for alternative and affordable ways to manage their cost of living (e.g., living in high-rise as opposed to landed properties, paying for a ride rather than owning a vehicle, sharing their costs with others). The younger generation are now less likely to spend their money on assets as compared to the older generation, especially given that the price of assets (e.g., cars, properties) and the cost of their maintenance have continued to increase at a rate greater than that of the wages earned by the working society [41].

As sustainable living through sharing practices (i.e., the activity of using, occupying, or enjoying a product [e.g., good, service] together with another party) begins to proliferate in our society through the advancement of technology (e.g., mobile apps, smart gadgets) and the necessity to reduce waste (i.e. minimizing and preventing the production of unwanted and unusable materials) and duplication of resources (i.e., the unnecessary process of recreating excessive and unused resources), it becomes increasingly important to understand the sharing economy with greater depth [55]. Noteworthily, in-depth knowledge about the sharing economy can help the society realize the market’s potential, enabling people to identify the advantages and disadvantages of the market as well as the necessary work required to improve the sharing economy and enhance the state of the market [13]. Ultimately, the increase in sharing activities in the society should eventually decrease the society’s cost of living and ensure that resources are efficiently managed, thereby avoiding resource underutilization and maximizing the returns of resource utilization [57].

1.2 Definition of the sharing economy

The definition of the sharing economy has been repeatedly cited and refined over time. Based on the plethora of definitions available, Acquier et al. [1] concludes that there are both narrow and broad views of the sharing economy due to the ever-changing nature of the market, which suggests that it is difficult to accurately define the sharing economy because its practice is never constant. Moreover, the concept of the sharing economy has also been subjected to interchangeable usage with collaborative consumption (e.g., Lim et al. [36]). Nevertheless, Belk [8] offers a distinction, stating that collaborative consumption is mainly motivated by making profit, whereas sharing involves more aspects of community and reciprocity from the parties involved. However, the distinction by Belk [8] appears to be specific to the concept of sharing from a social perspective rather than from an economic perspective, and thus, may not necessarily provide the best reflection of the current practices that transpire in the sharing economy.

Distinctions between collaborative consumption and conventional consumption have also been made; collaborative consumption is a system in which consumers can switch roles in being a consumer or a producer, thereby allowing consumers to directly collaborate with one another, which is an opportunity absent in conventional consumption (i.e., one-direction—e.g., purchase and consume or consume only) [20]. Puschmann and Rainer [54] argue that the difference between collaborative consumption and sharing is that collaborative consumption involves consuming goods and services in consumer-to-consumer (C2C) networks that are either coordinated through community-based online services or in business-to-consumer (B2C) models whilst sharing mostly involves consumption in C2C networks only. Other scholars have also pointed out that sharing does not involve material compensation and is mediated through social mechanisms while collaborative consumption takes in a third party (e.g., platform provider) and involve some form of monetary or non-monetary compensation [9]. Similarly, these definitions share the same shortcoming when ‘sharing’ is taken to represent ‘the practices in the sharing economy’ (i.e., it does not necessarily reflect the current practices of the sharing economy, where economic exchanges for sharing are present).

To this end, it is clear that conventional consumption is different from collaborative consumption. The difference between collaborative consumption and the sharing economy, however, remains untenable. Hence, it is no surprise that these concepts continue to be used interchangeably. The recent work by Lim [32, p. 7] provides a more inclusive definition of the sharing economy, taking into account compensatory and non-compensatory sharing practices: “The sharing economy is a marketplace that consists of entities (e.g., consumers, organizations) that innovatively and sustainably shape how marketing exchanges of valuable products and resources are produced and consumed through sharing, which can occur when entities take part in (e.g., divide and distribute) the actual or life-cycle use of a product or resource and communicate some form of information, and which can be scaled using technology.” In this regard, the usage of collaborative consumption and the sharing economy may be resolved by treating collaborative consumption as a practice in the sharing economy. Noteworthily, this definition of the sharing economy appears to be most comprehensive, recent, and reflective of current practices at the time of writing, and thus, is adopted in this paper.

1.3 The need for an in-depth understanding and review of the sharing economy

Academic interest in the sharing economy is equivalent to its adoption in practice—they are both burgeoning and promising [7].

From a practical standpoint, the sharing economy is a new economy, which renders its understanding relatively nascent as compared to the traditional economy. This highlights the necessity and importance for undertaking scholarly research that stakeholders can rely upon to gain an in-depth understanding of the sharing economy. Such research typically comes in the form of systematic reviews of the literature, which provide a one-stop reference for state-of-the-art insights of the field [37, 38].

From an academic standpoint, the sharing economy represents a fertile ground for new research. In fact, a plethora of research exists on the sharing economy, which is evident through the many reviews dedicated to this field. However, several noteworthy gaps or limitations exist in such reviews:

-

Insights limited to general themes and trends. For example, Kraus et al.'s [28] review highlights only the performance (e.g., productivity, impact) and science mapping (e.g., major themes) of research on the sharing economy, thereby offering only an overview rather than an in-depth understanding of the field. This limitation hinders the acquisition of the detailed peculiarities of the sharing economy.

-

Insights limited to specific sectors. For example, Cheng’s [14] review is concentrated on hospitality and tourism, whereas Hossain’s [26] review is focused on accommodation and transportation in the sharing economy. This limitation prevents the acquisition of a generalized understanding of the sharing economy.

-

Insights limited to specific perspectives. For example, Sutherland and Jarrahi’s [58] review is guided by the concept of platform mediation and provides only the theoretical perspectives of the sharing economy. Similarly, other scholars such as Ter Huurne et al. [59] have only focused on specific perspectives (e.g., trust) in their reviews. Such reviews are also generally focused and limited to the consumer perspective and thus overlooking the producer perspective. This limitation highlights that only a partial view rather than a holistic view can be obtained from these reviews when each review is read or taken independently.

-

Insights limited to articles selected without a review protocol. For example, Mont et al.'s [44] and Narasimhan et al.'s [47] reviews are not guided by a review protocol, which makes their reviews a critical review rather than a systematic review. This limitation may result in a biased view of the sharing economy because not all articles in the area have an equal chance of being selected for review.

1.4 The direction and contribution of the present review of the sharing economy

Given the extant gaps or limitations of prior reviews and the necessity and importance of gaining an in-depth understanding of the sharing economy, this paper aims to conduct a systematic review of the sharing economy, wherein:

-

(1)

A review protocol in the form of the PRISMA protocol is adopted to guide the systematic review;

-

(2)

Two frameworks in the form of the ADO (antecedents, decisions, outcomes) and TCM (theories, contexts, methods) frameworks are adopted to objectively and systematically organized the content or findings from the systematic review;

-

(3)

The sharing economy is reviewed as a whole rather than across specific sectors;

-

(4)

The characteristics of the sharing economy is unpacked in terms of the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes of consumers’ and producers’ participation in the sharing economy;

-

(5)

The theories, contexts, and methods for studying the sharing economy are revealed; and

-

(6)

The future directions for the sharing economy are presented.

In doing so, this paper contributes to theory by

-

(1)

Consolidating and reconciling extant knowledge on the sharing economy,

-

(2)

Highlighting the gaps in extant knowledge on the sharing economy, and

-

(3)

Providing suggestions for future research to overcome the gaps in extant knowledge on the sharing economy, and to practice by

-

(1)

Enriching understanding of the antecedents that influence consumer and producer participation in the sharing economy,

-

(2)

Enriching understanding of the decisions that consumers and producers can take in the sharing economy, and

-

(3)

Enriching understanding of the outcomes that can be evaluated or expected from consumers’ and producers’ participation in the sharing economy.

1.5 Structure of the present review of the sharing economy

The systematic review is organized as follows. First, the methodology of the systematic review is disclosed. This includes information pertaining to the decisions made in undertaking the systematic review. Next, the findings of the systematic review are presented. The findings will answer the question of “what do we know about the sharing economy”, specifically in terms of the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes of consumers’ and producers’ participation in the sharing economy, as well as the question of “how do we know about the sharing economy”, specifically in terms of the theories, contexts, and methods for studying the sharing economy. Finally, the systematic review concludes with key takeaways and future directions for the sharing economy.

2 Methodology

2.1 Systematic review

A systematic review is a form of secondary research that relies on a protocol to identify, select, and appraise existing studies to form an agenda for future studies [56]. The focus of a systematic review may be on a domain, method, or theory [49] and the method to conduct the review may take the form of a bibliometric, framework, meta-analysis, meta-systematic, or thematic approach [37].

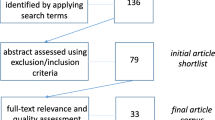

The present review is focused on the domain of the sharing economy. The PRISMA protocol, which consists of four stages (i.e., identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion), is adopted to guide the identification and selection process of relevant articles for the review [43]. The method to appraise the relevant articles is guided by a framework approach, wherein the ADO framework [50] and the TCM framework [51] form an integrated framework to objectively and systematically organize the findings of the review [39] (Fig. 1).

2.2 Review procedure

In accordance with the PRISMA protocol, the review process of this systematic review consists of four stages: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion [43].

In the identification stage, a snowballing technique was undertaken to identify a representative set of relevant articles on the sharing economy. The pursuit of a representative set rather than an exhaustive set is not new, and more importantly, an accepted practice for systematic reviews [58]. Inspired by snowball sampling, the snowballing technique is a form of ‘pearl growing’ to develop a representative set, wherein a ‘start set’ of articles (i.e., articles in the area of interest, in this case, the sharing economy) is initially identified and subsequently used to identify other articles. Unlike the alternative technique, which is to acquire all articles that return from a keyword search [52], the snowballing technique is a relatively new and underutilized technique for systematic reviews, though its use may be more common for empirical studies. Noteworthily, the value of the snowballing technique for systematic reviews resides in its utility for identifying ‘relevant’ articles in the area because the additional articles identified are directly ‘related’ to the ‘start set’ (i.e., the assumption is that ‘relation’ signifies ‘relevance’). For the present review, a ‘start set’ of 15 articles on the sharing economy was identified by the expert (first) author and the compilation of their references led to the identification of a total of 554 articles (inclusive of the ‘start set’).

In the screening stage, the 554 articles were screened according to the criteria informed by past scholars: publication period (i.e., 2001–2020, two decades), publication type (i.e., academic and peer-reviewed), and publication language (i.e., English) [52]. The screening of articles using these criteria led to the exclusion of 128 articles and the inclusion of 426 articles.

In the eligibility stage, the abstracts of the 426 articles were screened for topical relevance (i.e., the sharing economy), which led in the exclusion of 78 articles and the inclusion of 348 articles. Following the abstract screening, a duplicate screening was carried out, which resulted in the exclusion of 141 articles and the inclusion of 207 articles. Next, the full-text of articles were sourced from the university database. However, only the full-text of 198 articles were available (i.e., nine full-text articles were not available). The full-text of these available articles were read, which led to a further removal of 50 articles that lack topical relevance (i.e., the sharing economy does not take center stage in the article), and thus, leaving only 148 articles that were eligible for inclusion.

In the inclusion stage, a total of 148 eligible articles were included in a content analysis. This analysis was guided by the ADO-TCM integrated framework, where the antecedents, decisions, outcomes, theories, contexts, and methods of each article were coded in an Excel document and summarized for reporting. The summary of the review procedure is illustrated in Table 1.

3 Findings

The findings of the systematic review organized using the integrated ADO-TCM framework are depicted in Fig. 2 and discussed in the next sections.

3.1 What do we know about consumption and production in the sharing economy

3.1.1 Antecedents

Antecedents are essentially determining factors, and in the case of ADO, they are direct precursors of decisions and indirect precursors of outcomes [39]. Antecedents may be enablers or barriers depending on the direction of the effect that they exert (i.e., positive, negative). More often than not, an antecedent may appear as both an enabler and a barrier in a systematic review (e.g., [34], which may be reasonably attributed to the differences in contextual realities. Nevertheless, the consolidation of evidence in a systematic review can provide an overview of the state of the antecedent, enabling the establishment of generalized conclusions (i.e., general effect signaled through vote majority, wherein each vote represents an evidence of the effect of the antecedent from a study). The antecedents and their effects on consumption and production in the sharing economy are shown in Table 2. In total, eight categories of antecedents were revealed, namely trust, personal, economic, social, entrepreneurial, environmental, legal, and technological factors. These categories encapsulate a total of 17 antecedents or constructs, which are discussed in the next sections.

3.1.1.1 Trust factors

Trust factors comprise the characteristics and qualities that help create confidence in consumers and producers toward one another in the sharing economy. The review indicates that three constructs can be categorized as trust factors: communication, reputation, and information. In particular, the communication between consumers and producers is important as it helps to build a good relationship and thus fostering trust between both parties. The reputation of consumers or producers also affect the trust that either party has for one another due to the signaling effect of reputation. For instance, bad reviews of a consumer or a producer signal potential problems and thus may hamper the trust of the observing party. In that sense, the information about a consumer or a producer can influence the trust developed in the observing party of the observed party. Noteworthily, trust is an enabler when it is present (103 consumer votes, 56 producer votes) and a barrier when it is absent (59 consumer votes, 34 producer votes), especially among consumers as opposed to producers (as noted through the magnitude of votes).

3.1.1.2 Personal factors

Personal factors consist of the individual considerations taken by consumers and producers when deciding on their participation in the sharing economy. The review highlights two constructs as personal factors: commitment and opportunistic behavior. Specifically, the commitment of consumers and producers can affect their participation in the sharing economy, wherein greater commitment reflect greater participation. Similarly, the opportunistic behavior of consumers and producers signal that either party will participate in the sharing economy if they find good value to do so. Noteworthily, personal factors are generally viewed as enablers (25 consumer votes, 28 producer votes) rather than barriers (16 consumer votes, 19 producer votes) when consumers and producers are committed to the sharing economy and when they find value in consuming and providing shared products through this new economy, which is a fairly consistent observation for both parties (as seen through the number of votes).

3.1.1.3 Economic factors

Economic factors contain the commercial or financial benefits and costs of participating in the sharing economy. The review reveals two constructs as economic factors: cost and revenue of participating in the sharing economy. The cost of participating in the sharing economy affects both consumers and producers as consumers pay for shared products whereas producers incur costs to offer shared products in the sharing economy. The revenue of participating in the sharing economy refers to the earnings of producers when they offer shared products to consumers. Noteworthily, economic factors are generally viewed as enablers (44 consumer votes, 40 producer votes) rather than barriers (16 consumer votes, 17 producer votes), which is a fairly consistent sentiment among consumers and producers (as seen through the number of votes), and thus, indicating that both consumers and producers generally find economic value in participating in the sharing economy.

3.1.1.4 Social factors

Social factors encapsulate the influence of the society on consumers’ and producers’ participation in the sharing economy. The review indicates four constructs as social factors: culture, shared value, sense of community, and discrimination. Culture denotes the general acceptance and practice of the society in the sharing economy, wherein consumers and producers are likely to be participating in the sharing economy when such participation is a norm, and when such participation is not discriminated. Similarly, the presence of shared value where mutual exchanges are beneficial can enhance their participation, and the same can be said about the sense of community in the sharing economy. Noteworthily, social factors generally received mixed views among consumers and producers as the margin between their votes as enablers (35 consumer votes, 26 producer votes) and barriers (23 consumer votes, 21 producer votes) are relatively closer as compared to the other antecedent factors, which may be due to the newness of the sharing economy.

3.1.1.5 Entrepreneurial factors

Entrepreneurial factors refer to the creation and extraction of economic value. The review highlights two constructs as entrepreneurial factors: competition and entrepreneurial freedom. In particular, competition denotes the intensity of rivalry in the sharing economy, wherein greater rivalry for customers signals greater competition, whereas entrepreneurial freedom refers to the flexibility (e.g., workload, working hours) of harnessing the economic value in the sharing economy. Noteworthily, entrepreneurial factors are considered predominantly by producers, who view these factors as enablers (23 votes) rather than barriers (12 votes), which reaffirms the entrepreneurial freedom offered by the sharing economy and the growing potential of the customer market that is large enough for producers.

3.1.1.6 Environmental factors

Environmental factors relate to the conditions of the environment in which the sharing economy operates. The review reveals only one construct as part of environmental factors: environmental sustainability. In essence, environmental sustainability reflects the wellbeing of the environment, which requires conservation and protection. Noteworthily, environmental factors are generally viewed as enablers (38 consumer votes, 13 producer votes) rather than barriers (11 consumer votes, one producer vote) for consumer and producer participation in the sharing economy, thereby reaffirming the potential of the sharing economy as a more sustainable option than the traditional economy in safeguarding the sustainable wellbeing of the environment.

3.1.1.7 Legal factors

Legal factors refer to the laws and regulations that have been put in place by the government to regulate the sharing economy and safeguard the rights and wellbeing of consumers and producers who participate in this new economy. The review shows only one construct as part of legal factors: governance and legislation. In particular, consumers and producers in the sharing economy will have to adhere to whatever policies and standard operating procedures that are being imposed by authorities on shared products (e.g., provision of health and safety measures, payment of taxes). Noteworthily, legal factors are generally perceived as enablers (eight votes) as opposed to barriers (four votes) among consumers as these factors protect their rights. However, the same cannot be said for producers, who tend to view legal factors as barriers (18 votes) that they need to overcome in order to offer shared products in the sharing economy.

3.1.1.8 Technological factors

Technological factors relate to the characteristics of the technology that facilitate the marketing exchange and delivery of shared products among consumers and producers in the sharing economy. The review reveals two constructs as technological factors: ease of use and usefulness. That is to say, technologies (e.g., online booking and payment systems) in the sharing economy that are easy to use (e.g., easy to understand, learn, and seamless navigate) and useful (e.g., convenient, satisfies needs, solves issues) are likely to encourage and strengthen consumer and producer participation in the sharing economy. Noteworthily, technological factors are generally viewed as enablers (83 consumer votes, 28 producer votes) rather than barriers (48 consumer votes, 12 producer votes) of the sharing economy, thereby showcasing the value of technology in the consumption and production of shared products.

3.1.2 Decisions

Decisions essentially reflect behavioral performance or non-performance, and in the case of ADO, they are caused and shaped by antecedents while yielding an influence on outcomes [39]. In total, there are three categories of decisions in the sharing economy—i.e., price, book, and responsible conduct—and they are discussed in the next sections and summarized in Table 3.

3.1.2.1 Price

Price can be understood in two major ways: the consumer perspective and the producer perspective. From the consumer perspective, price manifest in consumers’ willingness to pay. From the producer perspective, price manifest as the amount that producers must receive in return for their offering. In this regard, price in the sharing economy is attached to shared products (e.g., home sharing, ride sharing). Noteworthily, the review indicates that trust (41 votes), technological (39 votes), economic (29 votes), and personal (17 votes) factors positively affect consumers’ willingness to pay for shared products and producers’ price-setting of shared products in the sharing economy. The same can be said for entrepreneurial factors (14 votes) for producers of shared products. However, environmental (20 votes), legal (16 votes), and social (13 votes) factors do not seem to have much significant influence on the price aspect of the sharing economy among consumers and producers alike, thereby indicating that the focus on pricing strategies should be based in the former as opposed to the latter group of factors.

3.1.2.2 Book

Like price, book can be understood from the consumer perspective and the producer perspective. From the consumer perspective, book denotes the request by consumers, whereas from the producer perspective, book reflects the producers’ acceptance of consumers’ request. In this regard, book manifest as the core of an exchange for shared products in the sharing economy (i.e., producers giving up shared products for a limited period in exchange for payment from consumers). Noteworthily, the review reveals that trust (52 votes), technological (41 votes), economic (36 votes), environmental (32 votes), and personal (20 votes) factors positively affect consumer request and producer acceptance of request for shared products in the sharing economy. However, social (19 votes) and entrepreneurial (17 votes) factors do not produce such a significant influence. Therefore, the focus on booking strategies should be guided by the former over the latter group of factors.

3.1.2.3 Responsible conduct

Responsible conduct reflects the ethical behavior of consumers and producers toward each other. Such behavior is especially important for the sharing economy due to the nature of shared products, which involves sharing rather than ownership. In this regard, responsible conduct is essential to ensure that the value of shared products is always maintained in ways that are not detrimental or do not diminish the future sharing of such products. Noteworthily, the review shows that trust (43 votes), technological (32 votes), social (21 votes), entrepreneurial (20 votes), legal (nine votes), and economic (eight votes) factors positively inculcate responsible conduct among consumers and producers in the sharing economy. However, environmental factors (24 votes) seem to have no significant effect on consumers’ and producers’ responsible conduct, which may be due to the social rather than environmental nature of responsible conduct understood in the context of the sharing economy. Interestingly, personal factors (14 votes) appear to have a negative effect on responsible conduct, which signals the detrimental effect of putting one’s self-interest over the community’s interest, thereby reaffirming the importance of being mindful about one’s responsible conduct when engaging in communal practices such as sharing in the sharing economy.

3.1.3 Outcomes

Outcomes essentially reflect the consequences of behavioral performance or non-performance, and in the case of ADO, they are indirect consequences of antecedents and direct consequences of decisions [39]. In total, there two categories of outcome in the sharing economy—i.e., loyalty and impact—and they are discussed in the next sections and summarized in Table 3.

3.1.3.1 Loyalty

Loyalty is a consistent behavior that one demonstrates over the long run and may manifest in finer-grained forms such as cognitive (belief and thinking), affective (emotional attachment), and conative (behavioral intention) or action (actual behavior) loyalty.

In terms of cognitive loyalty, the review demonstrates that economic (47 votes), social (21 votes), legal (19 votes), and technological (four votes) factors have a positive effect on the long-term belief and thinking of consumers and producers of the sharing economy. However, trust (39 votes), environmental (22 votes), entrepreneurial (20 votes), and personal (19 votes) factors had no such effect.

In terms of affective loyalty, the review indicates that trust (53 votes), personal (19 votes), environmental (12 votes), social (nine votes), and legal (five votes) factors have a positive effect on the long-term emotional attachment of consumers and producers toward the sharing economy. However, technological (24 votes), economic (18 votes), and entrepreneurial (three votes) factors had no such effect.

In terms of conative or action loyalty, the review reveals that trust (38 votes), technological (24 votes), personal (17 votes), and environmental (seven votes) factors have a positive effect on the long-term consumer and producer behavioral intention and actual behavior of participating in the sharing economy. However, social (15 votes), legal (eight votes), economic (seven votes), and entrepreneurial (five votes) factors had no such effect.

Taken collectively, these insights highlight the consensus of the majority in terms of the combination of factors that should be useful (most likely to have a positive effect) and less useful (less likely to have an effect) in cultivating the different forms of loyalty (cognitive, affective, and conative or action loyalty) among consumers and producers of shared products in the sharing economy.

3.1.3.2 Impact

Unlike loyalty, which concentrates on exchange outcomes in the long run, impact focuses on transactional outcomes regardless of time. In this review, the impact of consumer and producer participation in the sharing economy spans across three noteworthy outcomes: economic returns, value co-creation, and externalities.

Economic returns denote earnings and thus relates to producers rather than consumers. The review demonstrates that trust (47 votes), economic (42 votes), technological (29 votes), social (18 votes), entrepreneurial (11 votes), and personal (11 votes) factors indirectly play a crucial role in delivering positive economic returns to producers of shared products in the sharing economy. However, environmental (15 votes) and legal (five votes) factors had no such effect.

Value co-creation is a collaborative activity for creating value and thus reflects a synergistic process that involves multiple parties (e.g., consumers and producers) jointly creating multiple benefits for one another (e.g., enabling more sustainable consumption, reducing resource scarcity and underutilization). The review indicates that economic (45 votes), trust (33 votes), social (21 votes), technological (18 votes), personal (eight votes), and entrepreneurial (five votes) factors indirectly cultivate and facilitate value co-creation of shared products involving consumers and producers in the sharing economy. However, environmental (19 votes) and legal (2 votes) factors had no such effect.

Externalities refer to benefits or costs arising from behavioral performance or non-performance, and in the case of the sharing economy, they reflect the benefits or costs emerging from consuming and producing shared products. The review reveals that trust (27 votes), economic (17 votes), social (11 votes), technological (8 votes), and personal (7 votes) factors can indirectly give rise to externalities when consumers and producers participate in the sharing economy. However, entrepreneurial (eight votes), environmental (six votes), and legal (one vote) factors had no such effect.

Taken collectively, these insights highlight the consensus of the majority in terms of the combination of factors that should be useful (most likely to have a positive effect) and less useful (less likely to have an effect) in yielding positive economic returns for producers and promoting value co-creation and raising positive externalities among consumers and producers as a result of their participation in the sharing economy.

3.2 How do we know about consumption and production in the sharing economy

3.2.1 Theories

Theories provide a means to guide and support the development of insights (e.g., concepts, relationships [hypotheses, propositions]) about the studied phenomenon [39]. Numerous theories exist to study the sharing economy (Table 4). For example, the commitment-trust theory [45] can be adopted to explain the commitment and trust relationship among consumers and producers in the sharing economy [6]. The expectation-confirmation theory [48] can be applied to explain how consumer and producer expectations of the sharing economy are form and why the confirmation of those expectations leads to sharing behavior [5]. The legitimacy theory [19] can be deployed to explain how legitimacy in the sharing economy is established [27]. The self-determination theory [18] can be employed to explain how self-determination among consumers and producers shapes their behavior in the sharing economy [23]. The social exchange theory [25] can be used to explain the exchanges that consumers and producers partake in sharing economy [26]. The technology acceptance model [17] can be useful to explain what influences consumers and producers to adopt the sharing economy [40]. The theory of planned behavior [2] and theory of reasoned action [21] can be utilized to explain the decision-making process of consumers and producers in the sharing economy [30]. Finally, the value-percept theory [60] can be valuable to explain the values that consumers and producers avail and seek in the sharing economy [53]. Notwithstanding the promise of these theories, which indicate that the sharing economy is a fertile ground for theoretical application and extension, future research is encouraged to explore alternative theories, including the development of new theories and the adaptation and synthesis of existing theories, to further understanding of the sharing economy.

3.2.2 Contexts

Contexts provide a means to define the boundaries and specifics about the studied phenomenon [39]. The sharing economy can be examined from a country perspective (e.g., China, Italy, Malaysia, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States) as well as from a variant perspective (e.g., home sharing, ride sharing) (Table 5). The study of the sharing economy can also be in general, which is typically the case for conceptual studies (e.g., Lim [32]). More importantly, the body of knowledge on the sharing economy is expected to proliferate in tandem with the growth of digitalization and the need to address sustainability and resource scarcity issues, and crucial to ensuring that the future growth remains adequately diverse and inclusive is the study of the sharing economy across contexts, both from the single context and multi-context perspectives, wherein the former can offer depth in insights, whereas the latter can provide breadth in insights important for understanding the sharing economy.

3.2.3 Methods

Methods provide a means to validate the insights about the studied phenomenon [39]. In general, there are five methods that can be employed in scholarly research (Table 6). The conceptual method is adopted to theorize concepts, frameworks, models, and typologies of the sharing economy without data [32]. The qualitative method is applied to gain non-numerical insights (e.g., narratives and voices) of consumers and producers in the sharing economy [16]. The quantitative method is employed to acquire numerical or statistical insights of the sharing economy, wherein such insights may manifest in the form of associations (e.g., positive or negative significant or non-significant relationships) [10] or in the form of causality (i.e., control and manipulated conditions to establish causes and effects) [12]. Finally, the review method is used to consolidate insights, locate gaps and emerging trends, and present ways forward for the sharing economy [26]. Noteworthily, no one method is superior to another method, as each method is useful for its own purpose, and thus, should be viewed as collaborative rather than competitive tools for advancing knowledge in the field [37, 38]. More importantly, a method should always be chosen based on its relevance for achieving the research objective and answering the research question.

4 Conclusion

4.1 Concluding remarks and key takeaways

The sharing economy is a new economy in the digital era and arguably an extension of electronic commerce [29]. The continued growth and proliferation of academic interest as well as the sharing economy itself imply that gaining a holistic and in-depth understanding of this new economy is necessary and important. Therefore, the present study adopted a generalized approach to conduct a systematic review of the sharing economy, wherein this new economy is considered and reviewed as a whole rather than focusing on any specific perspective(s) (e.g., [58]), [59]) or sector(s) (e.g., [14, 26], thereby addressing the limitations of past reviews in the field.

Despite its generalized nature, this study proactively made a purposeful attempt to go beyond general themes and trends (e.g., [28]). In particular, the systematic review in this study pursued a deep dive into the distinct peculiarities of the sharing economy using the integrated ADO-TCM framework to organize its findings from a content analysis of 148 articles on the sharing economy. Noteworthily, the use of an integrated framework and a content analysis (e.g., vote counting) enabled the study to remain objective in its coding, classification, and reporting. The mindful design of this review was especially useful given that it involved more than a hundred articles [52].

Through the systematic review, this study offered macro (categories) and micro (constructs) insights into the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes of consumer and producer participation in the sharing economy, as well as useful insights on a plethora of theories, contexts, and methods for studying this novel reality. In particular, the review unpacked the trust, personal, economic, social, entrepreneurial, environmental, legal, and technological factors that impact on behavioral performance, loyalty, and impact factors among consumers and producers in the sharing economy. These insights contribute to theory by consolidating disparate and fragmented literature in the field [37] and revealing the nomological network of related factors [46] that explain consumer and producer participation in the sharing economy. These insights also contribute to practice by enabling industry practitioners (e.g., sharing economy platform companies) and policy makers to better a one-stop overview of the factors influencing consumer and producer participation in the sharing economy. This understanding can be used to cultivate and leverage on the enablers as well as address and mitigate the barriers that influence and shape the growth and magnitude of the participation of key stakeholders (consumers, producers) in the sharing economy.

The present systematic review also uncovered a range of theories, contexts, and methods that can be used to study the sharing economy. Though this information may appear to be descriptive, its value cannot be understated. Noteworthily, the use of theories is important to ground empirical investigations, wherein the rationales supporting hypotheses and propositions can be convincingly developed with the support of the logic espoused by theories and the evidence of extant studies that have relied upon those theories. Likewise, the understanding of contexts is especially important for enabling new research in the sharing economy to locate a suitable context and contribute new knowledge that would extend knowledge about that context. The understanding and subsequent use of context can also contribute to new theory when the peculiarities of the context is theorized, or extend the generalizability of existing theories when they are employed in the exploration of new contexts. Similarly, the understanding of methods is very much valuable, as methods should arguably be selected based on the problem at hand.

Last but not least, the findings herein the review are notably backed by the seminal use of a pragmatic, representative, and focused approach in the form of the snowballing technique, as well as a systematic, rigorous, and transparent review procedure in the form of the PRISMA protocol. In this regard, the review in this study is adequately motivated (e.g., multiple limitations), innovatively (e.g., the snowballing technique) and rigorously (e.g., the use of a review protocol) designed, and objectively reported (e.g., the use of an integrated organizing framework), which is well in line with the recent expectations of systematic reviews espoused by Lim et al. [37].

4.2 Limitations and suggestions for future research

Notwithstanding the contributions of this paper, several limitations exist, which can pave the way for future research that advances theoretical and practical insights of the sharing economy.

To begin, the findings of this review are limited to only a generalized overview of the sharing economy as a whole. While this focus was deliberate and sufficiently motivated, the value of reviews that adopt a specific focus such as specific perspectives and sectors cannot be understated. As existing reviews on the accommodation, hospitality, tourism, and transportation sectors exist [14, 26], alternative areas of the sharing economy could be explored, for example, coworking, crowdfunding, crowdsourcing, knowledge and talent sharing (e.g., citizen science; [15]), and reselling or retrading, among others. The context of the sharing economy itself could also be subject to further scrutiny, for example, physical-, digital-, omnichannel-, and in the future, metaverse-related sharing. Similarly, multi-review methods could also be deployed, for example, using a combination of bibliometric and framework review methods, thereby enabling the delivery of both general and specific insights in a single review study [37]. Nevertheless, a review of existing areas may be warranted, if a sufficient time period has lapse (e.g., 5–10 years), or if the field can be proven to have grown so large (e.g., more than 100%) that a new review is needed to take stock and reevaluate its state of progress [52].

Next, the findings of this review appear to be limited to two stakeholders: consumers and producers. Interestingly, the concept of prosumer, wherein an individual can be both a consumer and a producer, remains underexplored, and thus, could be given attention in future research. The same goes with other concepts that may be less prominent at this juncture in the sharing economy, for example, customer engagement [38] and personalization [11]. In addition, the scarce insights available on other potential stakeholders also signal the potential of exploring understudied stakeholders, for example, the platform operators that facilitate the sharing practices in the sharing economy. In this regard, future research that examines alternative stakeholders to consumers and producers are highly encouraged. The value of doing so may also reveal alternative perspectives that may not be apparent from the consumer and producer perspectives. For example, an exploration into the platform perspective could reveal noteworthy insights on the mechanisms that facilitate transactions in the sharing economy, including the key peculiarities (e.g., design, privacy, security) and technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence, big data analytics, blockchain, cloud computing, Internet of things, machine learning), which clearly did not emerged from the present review through consumer and producer perspectives, and understandably so given that the responsibilities of these peculiarities and technologies do not reside with consumers and producers but rather with the platform operators in the sharing economy.

Finally, the findings of this review highlight the relationships between different categories and constructs of antecedents, decisions, and outcomes. While this foundational understanding is useful and could be extended by exploring for new factors in areas lacking construct variety (e.g., environmental, legal, and technology factors) and taking alternative lenses, for example, the mediator and moderator perspectives, it is also equally important to pursue investigations that demonstrate how enablers and positive relationships can be developed, managed, and harnessed, and how barriers and negative relationships can be identified, managed, and mitigated. Such investigations will need to be supported by causal quantitative research designs, particularly those that adopt a conditional or an experimental approach, as such designs typically enable the establishment of causes and effects [33, 35]. Further reviews in this direction, wherein causal solutions are consolidated into a one-stop overview should be of great value too, especially among industry practitioners and policy makers in the sharing economy.

Taken collectively, it is hoped that this paper will be useful to gain both retrospective and prospective insights into the foundations of consumption and production in the sharing economy.

References

Acquier, A., Carbone, V., & Massé, D. (2019). How to create value(s) in the sharing economy: Business models, scalability, and sustainability. Technology Innovation Management Review, 9(2), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1215

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

Akande, A., Cabral, P., & Casteleyn, S. (2020). Understanding the sharing economy and its implication on sustainability in smart cities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 277, 124077.

Alemi, F., Circella, G., Handy, S., & Mokhtarian, P. (2018). What influences travelers to use Uber? Exploring the factors affecting the adoption of on-demand ride services in California. Travel Behaviour and Society, 13, 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.06.002

Balachandran, I., & Hamzah, I. (2017). The influence of customer satisfaction on ride-sharing services in Malaysia. International Journal of Accounting and Business Management, 5(2), 184–196.

Barbu, C. M., Florea, D. L., Ogarca, R. F., & Barbu, M. C. R. (2018). From ownership to access: How the sharing economy is changing the consumer behavior. Amfiteatru Economic, 20(48), 373–387. https://doi.org/10.24818/ea/2018/48/373

Barile, S., Ciasullo, M. V., Iandolo, F., & Landi, G. C. (2021). The city role in the sharing economy: Toward an integrated framework of practices and governance models. Cities, 119, 103409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103409

Belk, R. (2014). Sharing versus pseudo-sharing in Web 2.0. The Anthropologist, 18(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2014.11891518

Benoit, S., Baker, T. L., Bolton, R. N., Gruber, T., & Kandampully, J. (2017). A triadic framework for collaborative consumption (CC): Motives, activities, and resources & capabilities of actors. Journal of Business Research, 79(1), 219–227.

Böcker, L., & Meelen, T. (2017). Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.004

Chandra, S., Verma, S., Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Donthu, N. (2022). Personalization in personalized marketing: Trends and ways forward. Psychology & Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21670

Chen, J. M., de Groote, J., Petrick, J. F., Lu, T., & Nijkamp, P. (2020). Travellers’ willingness to pay and perceived value of time in ride-sharing: An experiment on China. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(23), 2972–2985.

Chen, Y., & Wang, L. (2019). Marketing and the sharing economy: Digital economy and emerging market challenges. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 28–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919868470

Cheng, M. (2016). Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57(1), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.003

Ciasullo, M. V., Carli, M., Lim, W. M., & Palumbo, R. (2022). An open innovation approach to co-produce scientific knowledge: An examination of citizen science in the healthcare ecosystem. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(6), 365–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-02-2021-0109

Cockayne, D. G. (2016). Sharing and neoliberal discourse: The economic function of sharing in the digital on-demand economy. Geoforum, 77(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.10.005

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388226

Ert, E., Fleischer, A., & Magen, N. (2016). Trust and reputation in the sharing economy: The role of personal photos in Airbnb. Tourism Management, 55(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.01.013

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Forno, F., & Garibaldi, R. (2015). Sharing economy in travel and tourism: The case of home-swapping in Italy. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 16(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008x.2015.1013409

Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2015). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047–2059. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23552

Hawlitschek, F., Teubner, T., & Gimpel, H. (2018). Consumer motives for peer-to-peer sharing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 204, 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.326

Homans, G. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1086/222355

Hossain, M. (2020). Sharing economy: A comprehensive literature review. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87(1), 102470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102470

Hwang, J. (2019). Managing the innovation legitimacy of the sharing economy. International Journal of Quality Innovation, 5(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40887-018-0026-0

Kraus, S., Li, H., Kang, Q., Westhead, P., & Tiberius, V. (2020). The sharing economy: A bibliometric analysis of the state-of-the-art. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(8), 1769–1786.

Kumar, S., Lim, W. M., Pandey, N., & Westland, J. C. (2021). 20 years of electronic commerce research. Electronic Commerce Research, 21(1), 1–40.

Lamberton, C. (2016). Collaborative consumption: A goal-based framework. Current Opinion in Psychology, 10(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.12.004

Li, C.X., & Lutz, J. (2019). Object history value in the sharing economy. Handbook of the Sharing Economy (pp. 75–90). Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lim, W. M. (2021). The sharing economy: A marketing perspective. Australasian Marketing Journal, 28(3), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.06.007

Lim, W. M. (2021). Conditional recipes for predicting impacts and prescribing solutions for externalities: The case of COVID-19 and tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 314–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1881708

Lim, W. M., & Rasul, T. (2022). Customer engagement and social media: Revisiting the past to inform the future. Journal of Business Research, 148, 325–342.

Lim, W. M., Ahmed, P. K., & Ali, M. Y. (2019). Data and resource maximization in business-to-business marketing experiments: Methodological insights from data partitioning. Industrial Marketing Management, 76, 136–143.

Lim, W. M., Gupta, G., Biswas, B., & Gupta, R. (2021). Collaborative consumption continuance: A mixed-methods analysis of the service quality-loyalty relationship in ride-sharing services. Electronic Markets. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-021-00486-z

Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Ali, F. (2022). Advancing knowledge through literature reviews: ‘What’, ‘why’, and ‘how to contribute.’ The Service Industries Journal, 42(7–8), 481–513.

Lim, W. M., Rasul, T., Kumar, S., & Ala, M. (2022). Past, present, and future of customer engagement. Journal of Business Research, 140, 439–458.

Lim, W. M., Yap, S.-F., & Makkar, M. (2021). Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? Journal of Business Research, 122, 534–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.051

Liu, Y., & Yang, Y. (2018). Empirical examination of users’ adoption of the sharing economy in China using an expanded technology acceptance model. Sustainability, 10(4), 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041262

Martin, C. J. (2016). The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecological Economics, 121(1), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.027

May, S., Königsson, M., & Holmstrom, J. (2017). Unlocking the sharing economy: Investigating the barriers for the sharing economy in a city context. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i2.7110

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group*. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535.

Mont, O., Palgan, Y. V., Bradley, K., & Zvolska, L. (2020). A decade of the sharing economy: Concepts, users, business and governance perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 269(1), 122215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122215

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800302

Mukherjee, D., Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., & Donthu, N. (2022). Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. Journal of Business Research, 148, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.042

Narasimhan, C., Papatla, P., Jiang, B., Kopalle, P. K., Messinger, P. R., Moorthy, S., Proserpio, D., Subramanian, U., Wu, C., & Zhu, T. (2018). Sharing economy: Review of current research and future directions. Customer Needs and Solutions, 5(1–2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40547-017-0079-6

Oliver, R. L. (1977). Effect of expectation and disconfirmation on Postexposure product evaluations: An alternative interpretation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(4), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.62.4.480

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0563-4

Paul, J., & Benito, G. R. G. (2018). A review of research on outward foreign direct investment from emerging countries, including China: What do we know, how do we know and where should we be heading? Asia Pacific Business Review, 24(1), 90–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2017.1357316

Paul, J., Parthasarathy, S., & Gupta, P. (2017). Exporting challenges of SMEs: A review and future research agenda. Journal of World Business, 52(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.01.003

Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR‐4‐SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), O1–O16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12695

Pu, R., & Pathranarakul, P. (2019). Sharing economy as innovative paradigm towards sustainable development: A conceptual review. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 8(1), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-7092.2019.08.33

Puschmann, T., & Rainer, A. (2016). Sharing economy. Journal of Business & Information Systems Engineering, 58(1), 93–99.

Richardson, L. (2015). Performing the sharing economy. Geoforum, 67(1), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.11.004

Sainaghi, R. (2020). The current state of academic research into peer-to-peer accommodation platforms. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89(1), 102555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102555

Schor, J. B., & Attwood-Charles, W. (2016). The “sharing” economy: Labor, inequality, and social connection on for-profit platforms. Sociology Compass, 11(8), e12493. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12493

Sutherland, W., & Jarrahi, M. H. (2018). The sharing economy and digital platforms: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management, 43, 328–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.07.004

Ter Huurne, M., Ronteltap, A., Corten, R., & Buskens, V. (2017). Antecedents of trust in the sharing economy: A systematic review. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(6), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1667

Westbrook, R. A., & Reilly, M. D. (1983). Value-percept disparity: An alternative to the disconfirmation of expectations theory of consumer satisfaction. Advances of Consumer Research, 10, 256–261. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/6120/volumes/

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged the Government of Malaysia for awarding a Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2019/SS01/SWIN/02/1) to support this research on the sharing economy.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tham, W.K., Lim, W.M. & Vieceli, J. Foundations of consumption and production in the sharing economy. Electron Commer Res 23, 2979–3002 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09593-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09593-1