Abstract

The aim of this paper is to investigate which factors influence the pattern of enforcement (violation) of basic rights among women trafficked for sexual exploitation. A conceptual framework is adopted where the degree of agency and the possibility to influence the terms of sex-based transactions are seen as conditional on the enforcement of some basic rights. Using data collected by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) on women assisted by the organization after having been trafficked for sexual exploitation, we investigate the enforcement (violation) of five uncompromisable rights, namely the right to physical integrity, to move freely, to have access to medical care, to use condoms, and to exercise choice over sexual services. By combining classification tree analysis and ordered probit estimation we find that working location and country of work are the main determinants of rights enforcement, while individual and family characteristics play a marginal role. Specifically, we find that (1) in lower market segments working on the street is comparatively less ‘at risk’ of rights violation; (2) there is no consistently ‘good’ or ‘bad’ country of work, but public awareness on trafficking within the country is important; (3) the strength of organised crime in the country of work matters only in conjunction with other local factors, and (4) being trafficked within one’s country, as opposed to being trafficked internationally, is associated with higher risk of rights violation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

ILO estimates that 43% of human trafficking in its entirety is solely for the purpose of sexual exploitation, and an additional 25% is for economic and sexual exploitation (ILO 2005, Fig. 1.4, p. 14). Both IOM data and the UNODC (2006) report give a higher figure (87%) for the share of trafficking for sexual exploitation, although UNODC counts sources of information rather than the persons that have been trafficked. See also Sect. 3 for more detailed descriptions of the UNODC and the IOM data sources.

For a philosophical reflection on this debate taking the view that such distinctions are salient see Dickenson (2006).

In a different area, Rozee’s analysis of rape (Rozee 1993) also develops the idea of a continuum based on social norms of distinct circumstances.

Levi-Strauss (1949) maintains that the whole relation of exchange that constitutes marriage is not defined between a man and a woman with each partner owing something and receiving something from the other. The relationship is defined between two groups of men and the woman features in it as an object of exchange, not as one of the partners in the exchange.

One of the few attempts to model prostitution in economics (Della Giusta et al. 2009) emphasizes the importance of alternative earnings opportunities that the last reported statement by Covre underlines.

Our translations and our additions in square brackets.

See the above quotations from Covre and Corso.

The IOM first interviews candidates for assistance using the ‘Screening Questionnaire’ and subsequently decides whether or not to grant assistance. A second questionnaire is administered to those selected for assistance (the ‘Assistance Questionnaire’). The latter includes practically all the questions in the Screening Questionnaire plus many more. Since the vast majority of screened applicants are granted assistance (80.4%), and practically no information is lost by using only the Assistance Questionnaire, our records are drawn exclusively from the latter.

Countries like Belarus and Ukraine appear in the IOM dataset not only as main countries of origin, but also of destination. At the same time, according to the UNODC (2006, p. 104), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries rarely feature as final destinations.

The trafficking flows for the three largest countries of origin are the following. From Moldova 25% of persons trafficked to FYROM, 19.2% to Serbia and Montenegro, 18.7% to Bosnia, 10.3% to Albania, and 17.2% trafficked internally. From Romania 22.4% of persons trafficked to FYROM, 20.9% to Bosnia, 13.1% to Serbia and Montenegro, 11.7% to Italy, 11.5% to Albania, and 9.5% trafficked internally. From Ukraine 11.3% trafficked to Serbia and Montenegro, 9.6% to FYROM, 9.1% to Bosnia, and 47% trafficked internally.

Mali is one of the largest countries of destination but was excluded from the covariates because of the extremely high incidence of missing answers for the dependent variables among victims in Mali.

Note that, following the suggestion from the UNODC (2006) and the literature on the connections between organised crime and trafficking (Becucci 2006, p. 25), the Organised Crime Index (OCI) of the World Economic Forum (Porter et al. 2005) was added to the original IOM dataset. The OCI is based on assessment of the degree to which business suffers costs from organised crime, and is measured on a 1–7 scale where 1 stands for ‘significant costs imposed’ and 7 for ‘no significant costs’ (see Transparency International 2004).

For further details on DTREG see Appendix 2.

Ideally, the five equations should be estimated allowing for possible correlation between the respective error terms, i.e. using seemingly unrelated regression techniques. However, this would involve maximum likelihood type estimation across a five level integral, a disproportionately costly computation especially given the quality of the data available.

It is well known that the marginal effect of a given covariate in ordered probit estimation is a function of the value and the sign of the estimated coefficient as well as of the value and sign of the estimated cut off points. There is therefore more than one possible set of marginal effects, depending on the scale of the dependent variable. For reasons of substance, as well as of space and conciseness, we have chosen here to report and comment on only the marginal effects for the severest violations of rights, i.e. the increase or decrease in the probability of suffering the worst restrictions. However, the coefficients reported in the appendix give a more complete account of the results, and it can be easily verified that the sign and significance of coefficients generally coincide with those of the marginal effects we have selected for comment.

Caution is necessary because the coefficient is negative and significant only in Model 2.

Since about two-thirds of all internal trafficking is accounted for by Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova, this particular finding could be partly driven by some factors common to these countries such as poor public awareness that favours this type of complicity.

About one tenth of the conventionally significant coefficients in Model 1 fell below the 5% threshold, but almost the same proportion exceeded it. The results are available from the authors upon request.

The standard name of the technique is Classification and Regression Tree Analysis, which reduces to Regression Tree in the case of the continuous dependent variable and to Classification Tree if the dependent variable is categorical by nature. The latter is exactly our case; hence in the paper we use the name ‘Classification Tree (CT) procedure’.

References

Anderson, B., & O’Connell Davidson, J. (2003). Is Trafficking in Human Being Demand Driven? A Multi-Country Pilot Study, IOM Migration Research Series, No. 15. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration.

Becucci, S. (2006). Criminalità Multietnica. I mercati illegali in Italia. Bari: Laterza.

Della Giusta, M., Di Tommaso, M. L., & Strom, S. (2009). Who’s watching? The market for prostitution services. Journal of Population Economics (forthcoming). doi:10.1007/s00148-007-0136-9.

Dickenson, D. (2006). Philosophical assumptions and presumptions about trafficking for prostitution. In C. L. van den Anker & J. Doomernik (Eds.), Trafficking and women’s rights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Di Tommaso, M. L., Shima, I., Strøm, S., & Bettio, F. (2009). As bad as it gets: Well being deprivation of sexually exploited trafficked women. European Journal of Political Economics, 25(2), 143–162.

European Commission. (2004). Report of the experts group on trafficking in human beings. Brussels: Directorate-General Justice, freedom and Security.

Garofalo, G. (2006). Towards a political economy of trafficking. In C. L. van den Anker & J. Doomernik (Eds.), Trafficking and women’s rights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Garofalo, G. (2007). ‘Un altro spazio per una critica femminista al ‘traffico’ in Europa’, Trickster, no. 3. Available at: http://www.trickster.lettere.unipd.it/archivio/3_prostituzione/numero/indice.html.

ILO. (2005). A global alliance against forced labour. Global Report under the Follow-up to the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

IOM. (2005). Second annual report on victims of trafficking in South-Easter Europe. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration.

IOM. (2006). Human trafficking survey: Belarus, Bulgaria, Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine. Prepared by the GfK Ukraine for the International Organization for Migration, Mission in Ukraine.

Kaye, M. (2003). The migration-trafficking nexus: Combating trafficking through the protection of migrants’ human rights. London: Anti-Slavery International.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1949). Les structures elementaires de la parente. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

Orfano, I. (Ed.). (2002). Article 18: Protection of victims of trafficking and fight against crime (Italy and the European Scenarios). Research report. Project ‘Osservatorio sull’applicazione dell’art. 18 del D. Lgs. n. 286 del 25/7/1998’—STOP Programme, European Commission—Promoting Organisation: Regione Emilia-Romagna—Co-ordinating Organisation: Associazione On the Road.

Patel, R., Balakrishnan, R., & Narayan, U. (2007). Explorations on human rights. Feminist Economics, 13(1), 87–116. doi:10.1080/13545700601086838.

Porter, M., Schwab, K., & Lopez-Claros, A. (2005). Global Competitiveness Report 2005–2006—Policies Underpinning Rising Prosperity, World Economic Forum, Palgrave: Macmillan.

Rozee, D. (1993). Forbidden or forgiven? Rape in cross-cultural perspective. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 17, 499–514. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1993.tb00658.x.

Tabet, P. (2004). La grande beffa Sessualità delle donne e scambio sessuo-economico, Rubettino Editore.

Transparency International. (2004). Transparency international corruption index 2004. Berlin: Transparency International Secretariat. Available at: http://www.transparency.org/pressreleases_archive/2004/2004.10.20.cpi.en.html.

UNODC. (2006). Trafficking in persons: Global patterns. Available at: http://www.unodc.org/pdf/traffickinginpersons_report_2006ver2.pdf.

Van den Anker, C. L., & Doomernik, J. (Eds.). (2006). Trafficking and women’s rights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

White, L. (1990). The comforts of home. Prostitution in colonial Nairobi. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Ministero Italiano per l’Università e la Ricerca (PRIN 2004). Our gratitude also goes to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva, for its kind permission to use the data, to Theodora Suter and Krieng Triumphavong for greatly facilitating transfer of the data, and to Sarah Craggs for her comments. We benefited enormously from the discussion among participants in the workshops organised in Siena and in Torino between 2005 and 2006 within the project ‘Analysis of migration flows at risk: prostitution and trafficking’. Theodora Suter from IOM and Kristiina Kangaspunta and Fabrizio Sarrica from the UNODC took part in these workshops and their contributions to the discussion were particularly valuable. The comments and suggestions of participants in subsequent seminars held in Reading, Salerno and Siena were also very important for the present version of this paper. Encouragement from Marina della Giusta helped throughout. A special thanks goes to Alina Veraschagina for her generous and valuable assistance at different stages of the paper. While this article draws upon data of the IOM, the opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

2.1 Selection of explanatory variables

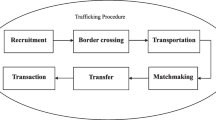

The Classification TreeFootnote 20 (CT) technique can be used to identify and rank the potential predictors in the order of their importance to explain the respect/violation of rights. In what follows, we provide an example of how this is done using variables taken from the IOM data set. For the sake of simplicity, however, we keep the number of variables at a minimum.

The CT analysis represents a binary recursive partitioning, as presented in Fig. 2. Assume the dependent variable ‘Freedom of movement’ is binary and takes value ‘0’ if no restriction is imposed and ‘1’ otherwise. Suppose that we need to rank the importance of seven variables in the data set as predictors of ‘Freedom of movement’: education, age, private apartment (location of work), Former Soviet Union (FSU, country of origin), international trafficking (as opposed to internal), single (marital status), unemployed (labour market status prior to departure). The variables that appear to be most important, as shown in Fig. 2 above, are placed on the top of the decision tree. These are, in descending order of importance, age, education, type of trafficking followed by country of origin, location of work, marital and previous labour market status.

Suppose that the value of 25 for the variable age splits the observations into two subgroups, that of individuals aged 25 years or less to the left of the original node, and that of individuals older than 25 years to the right. According to Fig. 2, being younger than 25 and being trafficked internationally predicts that the person will experience restrictions on the freedom of movement with the probability of 70%. It is also evident from the figure that what matters for the older group is education, not the type of trafficking. Being older than 25, having a higher level of education, and working in a private apartment leads to restriction on freedom of movement in 60% cases. Other patterns can be similarly identified down the tree.

It should be noted that the above example is hypothetical. It is a simplification of the analysis of the paper in several important respects. First, the dependent variable is assumed binary in the example, whereas the paper deals with dependent variables which are ordered, allowing for three categories. Second, the number of variables is kept at a minimum for the purpose of graphical exposition, whilst the analysis in the main part of the paper uses all variables from the IOM data set that report less than 50% missing values. Third, the example uses a single Classification Tree due to the fact that the dependent variable is binary. Our actual analysis resorts to the “Tree boost” method, which generates a large number of tree simultaneously in order to determine the predictive power of covariates.

One of the advantages of DTREG is its procedure for replacing missing values. The programme uses a technique involving surrogate splitters to estimate the values of predictor variables with missing values. Surrogate splitters are predictor variables that are less good at splitting a group than the primary splitter but yield similar splitting results by mimicking the splits produced by the primary splitter. When a row of observations is encountered that has a missing value on the primary splitter, DTREG searches the list of surrogate splitters and uses the one with the highest association with the primary splitter that has a non-missing value for the row. This feature of the program makes it possible to analyze the problematic dataset at hand, where the percentage of missing for certain variables is extremely high.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bettio, F., Nandi, T.K. Evidence on women trafficked for sexual exploitation: A rights based analysis. Eur J Law Econ 29, 15–42 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-009-9106-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-009-9106-x