Abstract

This study aims to explore profiles of preschool teachers’ intentions when they divide the children into subgroups. Interactionist perspectives, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, and a pedagogical perspective on preschool quality provide the foundation for the study’s theoretical framework. By applying a person-centered analytical procedure, the study analyzes preschool teachers’ considerations of a set of intentional indicators involved in grouping practices related to conditions for supportive classroom environment, opportunities for children’s play and interactions, and preschool teachers’ direct involvement in children’s learning. The sample consists of 698 preschool teachers from preschools in 46 municipalities in Sweden. Two intentional profiles were identified: a relational profile and an organizational profile. The patterns of play and learning opportunities, increasing communication and interaction, and opportunities for children to share their experiences and interests were the most distinctive patterns across the two profiles. Preschool teachers’ consideration of grouping practices as appropriate for working with a specific learning goal was equally emphasized in both profiles. These findings provide insight into preschool teachers’ pedagogical approaches and yield implications for the design of continuing professional development models for preschool teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study aims to investigate profiles of the intentions involved in Swedish preschool teachers’ practice to divide the children into small groups. In Swedish research, organizing the whole group into subgroups has been examined in relation to group size in preschool and its impact on organizational conditions for children’s well-being, learning, and development (Sheridan et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2018). By emphasizing the crucial role of teachers’ professional competence to intentionally organize the preschool classroom context and create conditions for high-quality classroom experiences, these studies have indicated the grouping practice as an important aspect of preschool quality. International studies have also shown that incorporating small-group activities into the daily working schedule is associated with high-quality pedagogical practices, providing opportunities for responsive and supportive classroom interactions (De Schipper et al. 2006; Slot et al. 2016), promoting and expanding children’s learning in specific subject areas (Cabell et al. 2013; Chien et al. 2010; Early et al. 2010; Leggett and Ford 2013), enhancing children’s well-being, and supporting their socioemotional development (Koivula and Hännikäinen 2017; Skalická et al. 2015).

Although the research supports the benefits of working in subgroups in preschool, it is surprising that thus far there has been no detailed investigation of preschool teachers’ intentions with grouping practice, either nationally or internationally. Moreover, a few limited studies in the field have shown that subgroups are frequently randomly organized without purposeful planning, intended mainly to handle preschool classroom management issues (Wasik 2008), and usually take place for a limited time (De Haan et al. 2014; Sheridan et al. 2014). To fill the gap in the existing literature, this study addresses the issue of preschool teachers’ intentions when they organize the whole group into subgroups and endeavors to contribute to the knowledge of this practice.

The study is guided by interactionist perspectives (Bergman et al. 2003), ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner 1979, 1986), and a pedagogical perspective of preschool quality (Sheridan 2007, 2009). On the basis of these theoretical standpoints, preschool teachers’ intentions involved in grouping practice are understood as embedded in various layers of the preschool system. This implies that broader policy and societal contexts as well as local decisions influence preschool teachers’ pedagogical and didactical approaches to children’s well-being, learning, and development, their professional background characteristics and the preschool’s organizational environment. Based on this rationale, the underlying hypothesis for this study is that there is diversity in preschool teachers’ intentions when they divide the children in small groups.

To capture this hypothesized diversity, this article employs latent profile analysis (LPA) as a person-centered analytical approach. This approach enables the identification of existing but unobserved subgroups of individuals that differ across similar dimensions (Collins and Lanza 2010). Identifying differences in preschool teachers’ pedagogical intentions provides insight into preschool teachers’ organizational approaches and contributes to the knowledge of their pedagogical and didactical premises. Preschool teachers’ intentions for grouping practices are explored by their considerations of a set of indicators related to conditions for supportive classroom environments, opportunities for children’s play, interaction, and learning, and preschool teachers’ direct involvement in children’s learning. The research question is:

What latent intentional profiles can be identified based on preschool teachers’ considerations related to grouping practices?

Research in the Field

Despite the scarcity of prior research on grouping practices in preschools, a growing body of research in the United States has examined how children’s time in preschool is allocated in various activity settings: whole-group, small-group, and free-choice settings (Ansari and Purtell 2016; Chien et al. 2010; Early et al. 2010; Fuligni et al. 2012; Goble and Pianta 2017). These studies have found that the small group activity setting is an effective strategy for academic instruction to support children’s engagement in academic activities and to scaffold teacher–child interactions. For example, in a study using observational data and applying latent class analysis (LCA) to examine profiles of children’s engagement in various activity settings, Chien et al. (2010) identified four profiles: (1) a free-play profile, where children spent the highest amount of time in free choice activities, (2) an individual instruction profile, (3) a group instruction profile, where children spent more time in whole-group and small-group activities, and (4) a scaffolding profile, where children spent more time in scaffolding interactions with teachers. The results suggested that children in the free-play profile demonstrated less gains in language/literacy and mathematics compared to the other three profiles.

In a large-scale study using person-centered modeling, Ansari and Purtell (2016) identified that 70% of a preschool day was spent in structured, teacher-directed activities and 30% in child-selected activities. Regarding how teachers structured their classrooms, they found diverse strategies, with teacher-directed, whole-group activities representing the highest proportion. While the effect sizes for the associations between classroom typologies and children’s early learning were relatively small, they found that the largest gains in academic achievement were in teacher-directed whole- or small-group activities. Didactic, teacher-managed small- and whole-group settings were also identified by Goble and Pianta (2017). This study specifically showed that the time spent in these activity settings was related to classroom gains in language and literacy skills. The authors claimed, however, that teachers’ pedagogical perspectives and effective engagement with children create opportunities to learn, regardless of classroom setting typologies.

A recent multi-case study was conducted in seven European countries to investigate associations between structural and process quality. The study showed that working in small groups was associated with a high level of process quality with respect to the quality of preschool teachers’ feedback provided during problem-solving activities and their responsiveness to children’s needs, views, and interests (Slot et al. 2016). The findings also indicated that incorporating small-group activities into the daily routines was an effective way to create rich learning environments in which a child-centered approach and children’s active participation could be combined with preschool teachers’ intentional involvement to stimulate children’s learning of specific concepts. When the structural aspects of preschool—such as the whole-group size and staff-to-child ratio—were not optimal, preschool teachers in the study provided most activities in small groups. This can be considered a group management dimension of working in subgroups reflecting the complex interplay between structural characteristics of preschool and the possibilities or constraints in everyday practice.

The organizational aspect of preschool teachers’ strategies to divide children into subgroups throughout the day was also emphasized by Alvestad et al. (2014), who explored preschool staff’s experiences in working with toddlers in large groups and with various group arrangements in Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. It was found that organizing children into smaller groups was associated with a harmonious atmosphere with respect to lower stress levels for both children and preschool staff, lower sound levels in the room, increased children’s concentration in learning activities, and high-quality interactions between children and preschool teachers. The quality of interactions was also emphasized by Salminen et al. (2014) in a study investigating how teachers arrange the composition of the groups to create and enhance the social life in Finnish preschool classrooms. The study found that working in pairs or small subgroups of less than four children was a significant way to concretely practice interactions by directly modeling social rules, encouraging cooperation with peers, and enhancing group coherence.

In Sweden, studies from a recent research project investigating the impact of group size on children’s well-being, learning, and development in preschool (Sheridan et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2016, 2018) found that organizing children into subgroups is a complex issue comprised of multiple aspects of preschool teachers’ everyday practices. Based on interviews with 24 preschool teachers, Sheridan et al. (2014) investigated their perspectives of how they organize child groups during the day. The study found that small-group organization was an optimal way for preschool teachers to deal with a large number of children and conduct their work according to the curriculum goals. The study identified, however, that the organized gatherings were short and infrequent in most preschools. Depending on what grounds preschool teachers based their dividing practices of the groups, the authors suggest that teachers’ criteria for making groups was related to both intentional and unintentional learning approaches, which become linked to pedagogical quality in preschool. In an intentional learning approach, the organization of groups is based on children’s participation and interests, and thus different types of groupings are a shared issue communicated between teachers and children. Preschool teachers in such organizational environments have a guiding role to create supportive conditions for children’s play and learning. In an unintentional learning approach, the organization of children into groups is based on aspects such as teachers’ working conditions, including staff–child ratio and child group composition, or the preschool’s environmental aspects, such as physical space or materials. The unintentional learning approach thereby creates limitations for children’s participation and influence, and it has often been associated with low preschool quality (Sheridan et al. 2014).

Theoretical Standpoints

This study draws on a holistic-interactionist perspective (Bergman et al. 2003), Bronfenbrenner’s (1979, 1986) ecological systems theory, and a pedagogical perspective of preschool quality (Sheridan 2007, 2009). These theoretical standpoints encompass aspects that are both interrelated and interwoven, implying an understanding of the complexity of multiple factors that may influence preschool teachers’ everyday practices and thereby their intentions with group organizing.

The fundamental tenet of a holistic-interactionist perspective is that “the individual as a whole is an active and intentional part of a complex and integrated person-environment system” (Magnusson and Stattin 2006, p. 401). From this perspective, individuals adapt, function, and develop through a process of dynamic interactions between their personal characteristics and the surrounding environment. This theoretical perspective supports a person-centered research method, where the research focus is on the individual level and individuals can be classified into subgroups on the basis of pattern similarity (Bergman et al. 2003).

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979, 1986) ecological systems theory is in line with the holistic- interactionist perspective. By emphasizing the central role of an individual’s agency, the ecological systems theory approaches the individual’s way of thinking, acting, and developing in an interdependency with multiple interrelated systemic contexts: macro-, exo-, meso-, micro-, and chrono-systems. This theoretical framework contributes to the examination of preschool teachers’ intentions with group organizing as constituted through reciprocal interactions between relationships among all actors in the micro-system (children, families, and preschool staff), local decisions on municipalities’ resource allocation affecting the organizational preschool environment, and societal and educational policy goals influencing preschool teachers’ pedagogical and didactical approaches. In this study, the ways these interactions affect preschool teachers’ grouping practices are discussed from a pedagogical perspective of preschool quality (Sheridan 2007, 2009).

A pedagogical perspective of quality is defined by four interrelated dimensions: the society, the preschool teacher, the child, and the context (Sheridan 2007, 2009). The dimension of society, on a macro level, embraces knowledge about policy-changing intentions, theoretical approaches to children’s learning and development, and preschools’ tasks and overall goals. The dimension of the preschool teacher includes his or her professional competence in terms of knowledge, practices, and values, creating conditions for children’s well-being, learning, and development. The dimension of the child embraces dominant theoretical perspectives on children’s participation and influence, such as how they experience and construct their learning through interactions with preschool staff, peers, and the physical environment and to what extent they influence and form their learning environment. The dimension of context includes the availability of human and material resources and how they are used and experienced by all actors, both locally and nationally, involved in a preschool. These interrelated dimensions influence preschool teachers’ pedagogical intentions and thereby their working methods and strategies to organize their everyday practices in preschools.

Materials and Methods

Sample

This study draws on data from a large Swedish survey investigating preschool teachers’ considerations of children’s learning and development in relation to group size in preschool (Williams et al. 2018). The survey data were collected between 2012 and 2013 through a web-based questionnaire. The questionnaire included information on preschool teachers’ backgrounds, group sizes in their preschools, their reasons for dividing children into subgroups, and considerations on children’s well-being, learning, and development in relation to group size. For the purpose of the current study, the information on preschool teachers’ intentions when organizing children into subgroups was analyzed. A total of 698 preschool teachers from 46 municipalities in Sweden answered the questionnaire. The municipalities differed with respect to their geographical and sociodemographic characteristics and the number of preschools and children in each municipality. The majority of respondents were female (97.75%), worked in municipal preschools (92.4%), and had an average age of 44 years [for detailed descriptive information on the sample, see Nasiopoulou et al. (2017)]. The study follows the Swedish Research Council’s (2017) ethical regulations for humanities and social sciences.

Measures

Preschool teachers’ intentional profiles with grouping practice were measured by 11 ordinal variables. These variables capture different intentions for preschool teachers’ grouping practices, among which teachers give their rank order for each intention. Thus, each variable ranges between 1 and 11, with 1 being high importance and 11 being low importance. The variables were related to four themes: conditions for a supportive and sustainable classroom environment, opportunities for children’s play, children’s interactions, and preschool teachers’ direct involvement in children’s learning. The theme of a supportive and sustainable classroom environment was measured by the indicators good sound level and calm working environment. Children’s play was measured by the indicators children’s opportunities to play and find their playmates. Three indicators were used to measure children’s interactions: opportunities to share their interests and experiences, opportunities for interaction, and opportunities to increase communication. The indicators teacher-initiated activities and work with specific learning objects were used to measure preschool teachers’ direct involvement in children’s learning. One variable named other was included in the analysis to provide respondents the opportunity to consider other aspects of importance that were not included in the question. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the indicators included in the analysis.

Additionally, preschool teachers’ professional background characteristics, including their graduation year from bachelor’s degree programs, continuing professional development (CPD), and years of working experience in preschool, were used as auxiliary variables in the analysis. These auxiliary variables were not used as indicators in the estimation of the latent intentional profiles but to describe possible relationships between preschool teachers’ professional background characteristics and the identified profiles of teachers’ intentions with grouping practices. These three variables were dummy coded in two categories with the values 0 and 1. For the variable graduation year, the year 1998 was the intersection point for categorization into the two categories (0 = graduated after 1998, 1 = graduated before 1998). The rationale behind this categorization was that in 1998, preschool was incorporated into the educational system, and the first curriculum came into force clarifying its pedagogical role, which might have affected preschool teachers’ pedagogical intentions for grouping practices. The variable years of working experience in preschool was coded as 0, corresponding to 9 years or less, and 1, corresponding to 10 years or more. Finally, preschool teachers who attended CPD activities were included in category 0 (yes), while those who did not were included in category 1 (no). Table 2 shows the descriptive information of these variables.

Analytical Method

Drawing on a holistic-interactionist perspective (Bergman et al. 2003) of individuals’ functioning in a specific environment, the current analysis assumes that there is diversity among preschool teachers’ intentions with grouping practices. To tackle this diversity, latent profile analysis (LPA) was applied (Hagenaars and McCutcheon 2002). LPA is a person-centered approach that describes differences among individuals and identifies subgroups who “function in a similar way at the organism level and in a different way relative to other individuals at the same level” (Magnusson 2003, p. 16). In other words, LPA identifies and describes existing but unobserved subgroups of individuals within a population who are characterized by heterogeneity with respect to the phenomenon under consideration (Bergman et al. 2003). The identification of these subgroups, referred to as latent classes/profiles, is inferred from individuals’ response patterns on a set of observed indicators for a given phenomenon (preschool teachers’ intentions with grouping practice in the current analysis). The profiles are discrete and mutually exclusive (Collins and Lanza 2010); that is, the response patterns are similar within profiles but different between profiles.

Analytical Process

The present analysis was performed using a three-step procedure with auxiliary variables treated as predictors for latent class membership (Asparouhov and Muthén 2014). According to this procedure, the latent class model is estimated first using only the latent class intentional indicators. Then, the most likely latent class model is created on the basis of posterior distribution obtained during the latent class model estimation in the first step. In the third step, the auxiliary variables are included in the analysis. In this final step, the most likely latent class model is regressed on the auxiliary variables, and the desired latent class model is estimated while considering the misclassifications identified in the second step (Asparouhov and Muthén 2014). The analysis was performed using the Mplus version 7.4 statistical package (Muthén and Muthén 2017).

To evaluate the precision of classification of individuals’ latent class membership and the optimal number of latent classes, multiple information criteria were considered as recommended by previous research (Nylund-Gibson and Masyn 2016). (1) Model fit indices using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), and the adjusted BIC (ABIC) were considered. Lower BIC, AIC, and ABIC values indicate the best-fitting model. For statistical testing of the optimal number of latent classes, the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin log likelihood ratio test and Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT) were considered. Non-significant test results support the latent class model with one less class (Nylund-Gibson and Masyn 2016). (2) Next, classification quality was examined regarding the entropy values [as suggested by Collins and Lanza (2010)]. An entropy value close to 1 indicates a perfect classification. (3) The parsimony and interpretability of the latent classes in practice were determined by the number of individuals assigned to each latent class (Collins and Lanza 2010). The models were estimated using a large number of random starting values in Mplus to avoid the local maximum likelihood problem (Goodman 1974).

Results

Identification of Classes

The LPA model was fitted to identify meaningful and discrete classes of preschool teachers’ intentions for grouping practices. Several models were estimated with different numbers of latent classes before determining the best model solution. The two-class solution was better than the three- and four-class solutions both statistically and substantively. Table 3 presents the model fit information criteria, the statistical tests, and the entropy values associated with each LPA model. Although the decreasing numbers of the AIC, BIC, and ABIC between the two- and three-class models indicated that the three-class model might be the best solution, the LMR-LRT tests provided non-significant p-values between the two- and three-class models. When examining the three-class model, it did not make substantive sense, as there was one small class with very few individuals (0.02% of the sample). Thus, based on the parsimony principle and the interpretability of the latent models (Collins and Lanza 2010; Nylund et al. 2007), the two-class model was judged to be a better solution. This was also supported by a high entropy value for the two-class solution, indicating high quality in the classification of individual preschool teachers. The latent class separation was also strong. The average probability of preschool teachers belonging in latent class one was 1. The estimated mean probability of these preschool teachers being in latent class two was 0. Preschool teachers in latent class two have an average probability of belonging in latent class two of 0.997 and a very low average probability of belonging in latent class one, 0.003. When examining the auxiliary variables as predictors for preschool teachers’ latent class membership, the results from the multinomial logistic regression showed that there were no significant differences across classes.

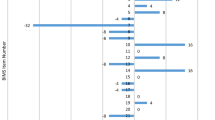

Profiles of Preschool Teachers’ Intentions

The two-class model revealed two latent profiles of preschool teachers’ intentions with grouping practices. Profile 1 contained the most preschool teachers in the sample (573; 82.1%), and Profile 2 contained 125 preschool teachers (17.9%). Table 4 shows the estimated means of each intentional indicator, given preschool teachers’ latent class membership. Low estimated means of each indicator (close to 1) correspond to a high emphasis on the respective indicator, as they are rank-ordered variables, with 1 representing high importance and 11 representing low importance. Profile 1 consists of the majority of preschool teachers, indicating a more prevalent profile. Preschool teachers in this profile are likely to put more emphasis on the following indicators: play and learning opportunities, increased communication and interaction, and opportunities for children to share their experiences and interests. Profile 2 comprises preschool teachers who have low estimated means in sound level, teacher-initiated activities, calm working environment, opportunities for children to find playmates, and other. The indicator working with a specific learning object was equally emphasized by preschool teachers in both profiles.

As the indicators related to children’s interactions were more distinct in Profile 1, this profile was labeled relational. Profile 2 was labeled organizational because the intentional indicators of calm working environment and sound level were more emphasized in this profile. The two intentional profiles are depicted in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to explore profiles of teachers’ intentions for grouping practices in Swedish preschools. By applying a person-centered methodological approach (LPA), the study intended to capture the hypothesized diversity embedded in preschool teachers’ intentions with grouping practices and identify latent profiles based on a set of indicators related to this practice. Exploring this potential diversity in preschool teachers’ intentions improves our understanding of group organizing practices and provides the research community with potential thresholds at which the benefits of working in small groups can be further investigated. The analysis revealed two profiles of preschool teachers’ intentions: a relational profile and an organizational profile. Play and learning opportunities, increased communication and interaction, and opportunities for children to share their experiences and interests were the most distinctive patterns differentiating the two profiles.

The relational profile was by far the largest, accounting for 82.1% of respondents, indicating that children’s interactions, play, and learning opportunities are fundamental for preschool teachers in this profile when organizing children into subgroups. In the organizational profile, the indicators of good sound level and calm working environment were more emphasized, suggesting that preschools’ physical ecology is very likely to be an influential aspect that directs teachers’ actual practices and affects their intentions with grouping practices.

Consistent with previous research (Booren et al. 2012; Slot et al. 2016), preschool teachers in the relational profile appeared to be more intentional in utilizing the grouping practice to consider children’s alternative viewpoints, provide children with opportunities to be more expressive with their peers, and support their active exploration and play. Given the emphasis on indicators related to children’s interactions, children’s interests and active engagement in joint play and learning activities can be seen as a starting point in preschool teachers’ intentions for grouping practices in this profile. Thus, despite the fact that preschool teachers in both profiles are the driving force in organizing children into subgroups, this practice can be considered child-centered and jointly constructed between children and preschool teachers and among children (Sylva et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2018). Furthermore, as the indicator of learning opportunities was the highest emphasized indicator within this profile, it is more likely that the relational profile reflects a social pedagogic approach (Bennett 2007) that has a long tradition in Swedish preschool practice. In this approach, social values are emphasized and children’s learning is grounded in their reciprocal interactions, shared experiences, and participation in joint play. From this perspective, this profile is related to the intentionally learning-oriented organized environment described by Sheridan et al. (2014) in which groupings, activities, and objects for learning are based on children’s participation and interest in learning.

The preschool teachers included in the organizational profile are more likely to organize children into smaller constellations to create a calm and sustainable preschool environment for children’s well-being, learning, and development. Previous research (Alvestad et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2018) has found that the physical environment (in terms of space, design, and sound level) is a key aspect in planning and arranging small-group activities. According to these studies, it can create both restrictions and options in preschool teachers’ everyday practice, depending on how it is designed. An unsuitable design combined with other preschool structural characteristics, such as large group size, diverse group composition, and a high child–staff ratio, have been associated with stressful working conditions, which in turn have a negative impact on preschool teachers’ and children’s emotional well-being. Although these structural aspects were not considered in the current analysis, one might speculate that they are very likely to be included in the indicator other, which is the highest emphasized indicator in this profile. The emphasis on the indicators of sound level and calm working environment support this consideration, indicating that preschool teachers in this profile considered the grouping practice as a way to manage possible physical and structural restrictions for optimal classroom functioning.

In addition to this managing perspective, a teacher-led perspective embracing a guiding and supporting intention could also be identified by the other two indicators with high emphasis in the organizational profile: teacher-initiated activities and providing children with opportunities to find playmates. This further suggests that organizing children into subgroups is a means for preschool teachers in this profile to set the stage for activities, for example, by introducing a specific topic about which they want the children to develop knowledge. This organizing principle reflects an activity-organized environment described by Sheridan et al. (2014) in which preschool teachers primarily decide the various groupings, spatial arrangements, and the kind of pedagogical activities provided to children. Additionally, preschool teachers in this profile considered grouping practices advantageous for facilitating children’s development of play relationships. This implies an intention to encourage children’s sense of belonging in the preschool community by scaffolding peer relationships and suggesting ways for children to work together (Salminen et al. 2014). Overall, the results suggest that preschool teachers in the organizational profile utilize grouping practices to establish an organized, calm, and supportive environment for children’s well-being, learning, and development.

It is noteworthy that the indicator of working with specific learning objects is equally emphasized in both profiles, indicating that grouping practices are a pedagogical strategy adopted by preschool teachers to expand children’s learning in specific content areas. This aligns with findings from studies on the association between activity settings and children’s academic learning (Ansari and Purtell 2016; Cabell et al. 2013; Goble and Pianta 2017) showing that teacher-managed activities, particularly in small-group settings, provide the opportunity for didactic teacher–child interactions linked to children’s learning gains. The finding is also in agreement with the study by Slot et al. (2016) on pedagogical practices, which found that conducting small-group activities within the whole group can create a supportive setting for children’s engagement in learning by incorporating their ideas into the teaching context and expanding their learning. This finding is of particular importance, as the revised preschool curriculum in Sweden (Swedish National Agency for Education 2019) highlights both a clarification of various subject areas such as language, mathematics, science, and technology, and an increased emphasis on preschool teachers’ teaching responsibility. Although this intentional indicator was equally emphasized in both profiles, it was not ranked by preschool teachers as of the highest importance. One interpretation of this result could be that preschool teachers in both profiles are very likely to consider children’s learning as dynamic and emergent through social interactions in a variety of learning opportunities throughout the day rather than in adult-arranged and directed instructional activities (Broström 2017).

Finally, an examination of the relationship between preschool teachers’ professional background characteristics and the identified latent profiles showed that these characteristics were not statistically significant to predict preschool teachers’ latent profile membership. This is partially consistent with La Paro et al. (2009), who found that teachers’ education level and experience were inconsistently related to groupings and activities offered to children. However, this was to some extent unexpected, given the research support of the positive effects of CPD on preschool teachers’ practices (Sheridan et al. 2009). One explanation could be that this indicator is a dummy-coded variable with two categories (yes/no) that does not indicate the type of CPD preschool teachers attended. Another explanation could be that the data were collected during a period when CPD efforts, both at the national and local level, were not systematic (Nasiopoulou et al. 2017). Further studies are needed to investigate these aspects.

Limitations

While this study provides insights into the plurality of preschool teachers’ intentions for grouping practices, there are several limitations to be considered. Because of the lack of studies examining grouping practices, particularly involving person-centered modeling, this study was primarily exploratory without a priori defined intentional indicators, which could have been used to more accurately describe the profiles. Lanza et al. (2010) emphasized that when a study is exploratory without prior research guiding the selection of indicators, the results can be dependent on sample characteristics. Moreover, a specific concern is related to the type of variables used as intentional indicators. These are ranked variables, and preschool teachers’ ranking of one variable is related to the rank of the other variables. This implies that the profiles can be considered to be reflective of each other. However, the differences in estimated means between the two profiles are adequately large to identify some trends in preschool teachers’ intentions with grouping practices, providing useful information for future research to further investigate this practice. Another concern is related to the indicator of other, which was not followed by a comment field to gather additional intentional indicators, and thus, only speculations can be made. These considerations call for caution in interpreting and generalizing the results, and replication of the current study is necessary.

Conclusions

Overall, the results from this profiling study suggest that two perspectives are embraced in preschool teachers’ intentions with grouping practice: a child-centered perspective and an adult-led perspective. Both perspectives appear to be constructed in interactions with ecological resources, societal values, and educational policy goals affecting preschool teachers’ intentions for grouping practices (Bronfenbrenner 1979, 1986; Sheridan 2007, 2009). Although the intention to support children’s sense of belonging to a group and provide opportunities for children’s play and learning emerged in both profiles, managing physical and structural preschool conditions was given considerably more weight by preschool teachers in the organizational profile. This indicates the complexity of preschool teachers’ everyday practices encompassed by decisions in the exo-system (Bronfenbrenner 1979, 1986) that may conflict with preschool teachers’ pedagogical beliefs or intentions when planning and structuring the children’s learning environment. Although associations between the two profiles and preschool quality were beyond the scope of this study, this raises the question of what aspects are prioritized by preschool teachers for optimizing children’s learning and development when they plan and implement grouping practices. Preschool teachers’ understanding and interpretation of the curriculum goals, employment of ecological resources, and theoretical perspectives on children’s participation and influence are the core aspects of preschool pedagogical quality (Sheridan 2007, 2009). Different perspectives create different quality conditions for children’s well-being, learning, and development. From this perspective, these results can contribute to the design of CPD initiatives to prioritize the types of specialized knowledge needed for certain preschool teachers and across distinctive work settings and conditions.

References

Alvestad, T., Bergem, H., Eide, B., Johansson, J.-E., Os, E., Pálmadóttir, H., et al. (2014). Challenges and dilemmas expressed by teachers working in toddler groups in the Nordic countries. Early Child Development and Care,184(5), 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.807607.

Ansari, A., & Purtell, K. M. (2016). Activity settings in full-day kindergarten classrooms and children’s early learning. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,38, 23–32.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling,21(3), 329–341.

Bennett, J. (2007). Curriculum issues in national policy-making. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal,13(2), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930585209641.

Bergman, L. R., Magnusson, D., & El Khouri, B. M. (2003). Studying individual development in an interindividual context. New York: Psychology Press.

Booren, L. M., Downer, J. T., & Vitiello, V. E. (2012). Observations of children’s interactions with teachers, peers, and tasks across preschool classroom activity settings. Early Education and Development,23(4), 517–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2010.548767.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology,22, 723–742.

Broström, S. (2017). A dynamic learning concept in early years’ education: A possible way to prevent schoolification. International Journal of Early Years Education,25(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2016.1270196.

Cabell, S. Q., DeCoster, J., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2013). Variation in the effectiveness of instructional interactions across preschool classroom settings and learning activities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,28, 820–830.

Chien, N. C., Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Pianta, R. C., Ritchie, S., Bryant, D. M., et al. (2010). Children’s classroom engagement and school readiness gains in prekindergarten. Child Development,81, 1534–1549.

Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. New York: Wiley.

De Haan, A. K. E., Elbers, E., & Leseman, P. P. M. (2014). Teacher- and child-managed academic activities in preschool and kindergarten and their influence on children’s gains in emergent academic skills. Journal of Research in Childhood Education,28(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2013.851750.

De Schipper, E., Riksen-Walraven, M., & Geurts, S. (2006). Effects of child-caregiver ratio on the interactions between caregivers and children in child-care centers: An experimental study. Child Development,77(4), 861–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00907.

Early, D. M., Iruka, I. U., Ritchie, S., Barbarin, O. A., Winn, D.-M. C., Crawford, G. M., et al. (2010). How do pre-kindergarteners spend their time? Gender, ethnicity, and income as predictors of experiences in prekindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,25, 177–193.

Fuligni, A. S., Howes, C., Huang, Y., Hong, S. S., & Lara-Cinisomo, S. (2012). Activity settings and daily routines in preschool classrooms: Diverse experiences in early learning settings for low-income children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,27, 198–209.

Goble, P., & Pianta, R. (2017). Teacher-child interactions in free choice and teacher-directed activity settings: Prediction to school readiness. Early Education and Development,28(8), 1035–1051.

Goodman, L. A. (1974). Exploratory latent structure analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika,61(2), 215–231.

Hagenaars, J. A., & McCutcheon, A. L. (2002). Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koivula, M., & Hännikäinen, M. (2017). Building children’s sense of community in a day care centre through small groups in play. Early Years,37(2), 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1180590.

La Paro, K. M., Hamre, B. K., Locasale-Crouch, J., Pianta, R. C., Bryant, D., Early, D., et al. (2009). Quality in kindergarten classrooms: Observational evidence for the need to increase children’s learning opportunities in early education classrooms. Early Education and Development,20(4), 657–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280802541965.

Lanza, S. T., Rhoades, B. L., Nix, R. L., & Greenberg, M. T. (2010). Modeling the interplay of multilevel risk factors for future academic and behavior problems: A person-centered approach. Development and Psychopathology,22(2), 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000088.

Leggett, N., & Ford, M. (2013). A fine balance: Understanding the roles educators and children play as intentional teachers and intentional learners within the early years learning framework. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood,38(4), 42–50.

Magnusson, D. (2003). The person approach: Concepts, measurement models, and research strategy. In S. C. Peck & R. W. Roeser (Eds.), New directions for child and adolescent development: Person-centered approaches to studying development in context (pp. 3–23). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Magnusson, D., & Stattin, H. (2006). The person in context: A holistic-interactionistic approach. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 400–464). New York: Wiley.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus users guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nasiopoulou, P., Williams, P., Sheridan, S., & Yang Hansen, K. (2017). Exploring preschool teachers’ professional profiles in Swedish preschool: A latent class analysis. Early Child Development and Care,189(8), 1306–1324. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1375482.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling,14, 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396.

Nylund-Gibson, K., & Masyn, K. E. (2016). Covariates and mixture modeling: Results of a simulation study exploring the impact of misspecified effects on class enumeration. Structural Equation Modeling,23(6), 782–797.

Salminen, J., Hännikäinen, M., Poikonen, P. L., & Rasku-Puttonen, H. (2014). Teachers’ contribution to the social life in Finnish preschool classrooms during structured learning sessions. Early Child Development and Care,184(3), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.793182.

Sheridan, S. (2007). Dimensions of pedagogical quality in preschool. International Journal of Early Years Education,15(2), 197–217.

Sheridan, S. (2009). Discerning pedagogical quality in preschool. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research,53(3), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830902917295.

Sheridan, S. M., Edwards, C. P., Marvin, C. A., & Knoche, L. L. (2009). Professional development in early childhood programs: Process issues and research needs. Early Education and Development,20(3), 377–401.

Sheridan, S., Williams, P., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2014). Group size and organizational conditions for children’s learning in preschool: A teacher perspective. Educational Research,56(4), 379–397.

Skalická, V., Belsky, J., Stenseng, F., & Wichstrøm, L. (2015). Preschool age problem behaviour and teacher-child conflict in school: Direct and moderation effects by preschool organization. Child Development,86(3), 955–964.

Slot, P. L., Cadima, J., Salminen, J., Pastori, G., & Lerkkanen, M. K. (2016). Multiple Case Study in Seven European Countries Regarding Culture-Sensitive Classroom Quality Assessment. Report D2.3. Jyväskylä, Finland: Curriculum and Quality Analysis and Impact Review of European Early Childhood Education and Care.

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2019). Curriculum for the preschool, Lpfö-18. Retrieved April 29, 2019 from https://www.skolverket.se/sitevision/proxy/publikationer/svid12_5dfee44715d35a5cdfa2899/55935574/wtpub/ws/skolbok/wpubext/trycksak/Blob/pdf4049.pdf?k=4049.

Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good research practice. Retrieved May 14, 2019 from https://www.vr.se/english/analysis-and-assignments/we-analyse-and-evaluate/all-publications/publications/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2010). Early childhood matters: Evidence from the effective pre-school and primary education project. London: Routledge.

Wasik, B. (2008). When fewer is more: Small groups in early childhood classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal,35, 515–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-008-0245-4.

Williams, P., Sheridan, S., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2016). Barngruppens storlek i förskolan. Konsekvenser för utveckling och kvalitet [Group Size in Swedish Preschools: Consequences for Development and Quality]. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur.

Williams, P., Sheridan, S., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2018). A perspective of group size on children’s condition for wellbeing, learning and development in preschool. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research.. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1434823.

Acknowledgement

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg.

Funding

This study was supported by Swedish Research Council under Grant number 721-2011-05535.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nasiopoulou, P. Investigating Swedish Preschool Teachers’ Intentions Involved in Grouping Practices. Early Childhood Educ J 48, 325–335 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00988-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00988-8