Abstract

Background

Many programs and interventions are available to support families of young children, yet engagement and participation in these programs is often inconsistent. One explanation for poor engagement is that program parameters may not align with participant preferences. Further, preferred program components may vary across demographic groups.

Objective

In the present experiment, a best–worst scaling approach was utilized to ascertain parental preferences for early intervention programming.

Methods

Four hundred twenty-six parents of young children answered a set of 27 best–worst scaling questions regarding preferred components of early intervention programs.

Results

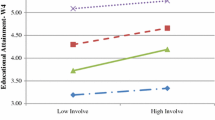

Overall results indicated that the most preferred aspect of program descriptions were those that emphasized parent and child outcomes (e.g., increased academic readiness, increased educational attainment). Parameters such as the provision of free childcare and teaching through experiential activities were also highly preferred. Programs held during a weekend, lasting 120 min, attended alone, led by a parent, attended without parent–child interactions, lasting 16 weeks, requiring paid or no childcare, and providing no food were least preferred. Although in general preferences were consistent across parents, there were significant differences in preferences across subgroups of parents.

Conclusions

Improvements in child outcomes were the most preferred attribute of early intervention programming. Few differences between subgroups of parents were observed. In cases where there were differences, mothers and single parents preferred some program activities to be separate from the child’s other parent. Parents from minority groups preferred programs that also included components directed at their own development as well (e.g., job training).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Avellar, S. M., Dion, R., Clarkwest, A., Zaveri, H., Asheer, S., Borradaile, K., et al. (2011). Catalog of research: Programs for low-income fathers. OPRE Report #2011-20. Washington, D.C.: OPRE, ACF, US DHHS.

Bagner, D. M. (2013). Father’s role in parent training for children with developmental delay. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 650–657.

Baker, C. N., Arnold, D. H., & Meagher, S. (2011). Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science, 12, 126–138.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological), 57, 289–300.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20, 351–368.

Brandon, D. M., Long, J. H., Loraas, T. M., Mueller-Phillips, J., & Vansant, B. (2014). Online instrument delivery and participant recruitment services: Emerging opportunities for behavioral accounting research. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 26, 1–23.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Is early intervention effective? Day Care and Early Education, 2, 14–18.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5.

Calzada, E. L. (2010). Bringing culture into parent training with Latinos. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17, 167–175.

Calzada, E. J., Basil, S., & Fernandez, Y. (2012). What Latina mothers think of evidence-based parenting practices: A qualitative study of treatment acceptability. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20, 362–374.

Chacko, A., Wymbs, B. T., Wymbs, F. A., Pelham, W. E., Swanger-Gagne, M. S., Girio, E., & O’Connor, B. (2009). Enhancing traditional behavioral parent training for single mothers of children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38, 206–218.

Chase-Lansdale, P. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2014). Two generation programs in the twenty-first century. The Future of Children, 24, 13–39.

Chrzan, K. & Patterson, M. (2006). Testing for the optimal number of attributes in MaxDiff questions. In 2006 sawtooth software proceedings, Sequim, Washington.

Comer, J. S., Chow, C., Chan, P. T., Cooper-Vince, C., & Wilson, L. A. S. (2013). Psychosocial treatment efficacy for disruptive behavior problems in very young children: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 26–36.

Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., & Wong, J. J. (2009). Promoting fathers’ engagement with children: Preventive interventions for low-income families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71, 663–679.

Craig, B. M., Hays, R. D., Pickard, A. S., Cella, D., Revicki, D. A., & Reeve, B. B. (2013). Comparison of US panel vendors for online surveys. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15, e260.

Cunningham, C. E., Deal, K., Rimas, H., Buchanan, D. H., Gold, M., Sdao-Jarvie, K., & Boyle, M. (2008). Modeling the information preferences of parents of children with mental health problems: A discrete choice conjoint experiment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 1123–1138.

Cunningham, C. E., Deal, K., Rimas, H., Chen, Y., Buchanan, D. H., & Sdao-Jarvie, K. (2009a). Providing information to parents of children with mental health problems: A discrete choice conjoint analysis of professional preferences. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 1089–1102.

Cunningham, C. E., Vaillancourt, T., Rimas, H., Deal, K., Cunningham, L., Short, K., & Chen, Y. (2009b). Modeling the bullying prevention program preferences of educators: A discrete choice conjoint experiment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 929–943.

Cunningham, C. E., Chen, Y., Deal, K., Rimas, H., McGrath, P., Reid, G., & Corkum, P. (2013). The interim service preferences of parents waiting for children’s mental health treatment: A discrete choice conjoint experiment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 865–877.

Downer, J. T. (2007). Father involvement during early childhood. In R. Pianta, M. J. Cox, & K. L. Snow (Eds.), School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability (pp. 329–354). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, Publishing.

Fabiano, G. A. (2007). Father participation in behavioral parent training for ADHD: Review and recommendations for increasing inclusion and engagement. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 683–693.

Fabiano, G. A., Vujnovic, R. K., Waschbusch, D. A., Yu, J., Mashtare, T., Pariseau, M. E., & Smalls, K. J. (2013). A comparison of experiential versus lecture training for improving behavior support skills in early educators. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 450–460.

Fantuzzo, J., Childs, S., Stevenson, H., Coolahan, K. C., Ginsburg, M., Gay, K., & Watson, C. (1996). The head start teaching center: An evaluation of an experiential, collaborative training model for Head Start teachers and parent volunteers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 11, 79–99.

Feinberg, E., Silverstein, M., Donahue, S., & Bliss, R. (2011). The impact of race on participation in Part C of early intervention services. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32, 284–291.

Finn, A., & Louviere, J. J. (1992). Determining the appropriate response to evidence of public concern: The case of food safety. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 11, 12–25.

Heckman, J. J. (2000). Policies to foster human capital. Research in Economics, 54, 3–56.

Heckman, J. J. (2011). The economics of inequality: The value of early childhood education. American Educator, 35, 31–47.

Heen, M. S. J., Lieberman, J. D., & Miethe, T. D. (2014). A comparison of different online sampling approaches for generating national samples. University of Nevada Las Vegas, NV: UNLV Center for Crime and Justice Policy.

Hseuh, J. D., Principe Alderson, E., Lundquist, C., Michalopoulos, D., Gubits, D., & Knox, V. (2012). The supporting healthy marriage evaluation: Early impacts on low-income families. New York, NY: MDRC.

Ingoldsby, E. M. (2010). Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 629–645.

Kazdin, A. E., Holland, L., & Crowley, M. (1997). Family experience of barriers to treatment and premature termination from therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 453–463.

Lee, C. M., & Hunsley, J. (2006). Addressing coparenting in the delivery of psychological services to children. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 13, 53–61.

Ludwig, J., & Phillips, D. A. (2008). Long-term effects of Head Start on low-income children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136, 257–268.

McCurdy, K., & Daro, D. (2001). Parent involvement in family support programs: An integrated theory. Family Relations, 50, 113–121.

McWayne, C., Downer, J. T., Campos, R., & Harris, R. D. (2013). Father involvement during early childhood and its association with children’s early learning: A meta-analysis. Early Education and Development, 24, 898–922.

Miller, G. E., & Prinz, R. J. (2003). Engagement of families in treatment for childhood conduct problems. Behavior Therapy, 34, 517–534.

Obama, B. (2013). Fact sheet President Obama’s plan for early education for all Americans. Washington, DC: White House Office of the Press Secretary.

Orme, B. (2009). MaxDiff analysis: Simple counting, individual-level logit, and HB. Sequim, WA: Sawtooth Software Inc.

Pleck, J. H. (1997). Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Prinz, R. J., & Miller, G. E. (1994). Family-based treatment for childhood antisocial behavior: Experimental influences on dropout and engagement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 645–650.

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12.

Reyno, S. M., & McGrath, P. J. (2006). Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems—A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 99–111.

Ross, M., Bridges, J. F. P., Ng, X., Wagner, L. D., Frosch, E., & dosReis, S. (2015). A best–worst scaling experiment to prioritize caregiver concerns about ADHD medication for children. Psychiatric Services, 66, 208–211.

Sanders, M. R., & Kirby, J. N. (2012). Consumer engagement and the development, evaluation, and dissemination of evidence-based parenting programs. Behavior Therapy, 43, 236–250.

Sawtooth Software, Inc. (2013). Sawtooth software technical paper series: The MaxDiff system technical paper, version 8. North Orem, Utah: Sawtooth Software, Inc.

Schatz, N. K., Fabiano, G. A., Cunningham, C. E., dosReis, S., Waschbusch, D. A. et al. (2015). Systematic review of patients’ and parents’ preferences for ADHD treatment options and processes of care. The Patient: Patient Centered Outcomes Research, 8, 483–497.

Snell-Johns, J., Mendez, J. L., & Smith, B. H. (2004). Evidence-based solutions for overcoming access barriers, decreasing attrition, and promoting change with underserved families. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 19–35.

Spoth, R., & Redmond, C. (1993). Identifying program preferences through conjoint analysis: Illustrative results from a parent sample. American Journal of Health Promotion, 8, 124–133.

Tiano, J. D., & McNeil, C. B. (2005). The inclusion of fathers in behavioral parent training: A critical evaluation. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 27, 1–28.

Trends, C. (2002). Charting parenthood: A statistical portrait of fathers and mothers in America. Washington, DC: Child Trends.

U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). A call to commitment: Fathers’ involvement in children’s learning. Washington, D.C.: Author.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start. (2011). The Head Start parent, family, and community engagement framework: Promoting family engagement and school readiness from prenatal to age 8. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. DHHS, ACF, Head Start Bureau. (2004). Building blocks for father involvement: Building block 1—Appreciating how fathers give children a head start. Washington, D.C.: U.S. DHHS, ACF.

Wadsworth, M. E., Santiago, C. D., Einhorn, E., Etter, E. M., Rienks, S., & Markman, H. (2010). Preliminary efficacy of an intervention to reduce psychosocial stress and improve coping in low-income families. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48, 257–271.

Waschbusch, D. A., Cunningham, C. E., Pelham, W. E., Rimas, H. L., Greiner, A. R., Gnagy, E. M., & Hoffman, M. T. (2011). A discrete choice conjoint experiment to evaluate parent preferences for treatment of young, medication naïve children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 546–561.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammon, M. (2004). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 105–124.

Weigold, A., Weigold, I. K., & Russell, E. J. (2013). Examination of the equivalence of self-report survey-based paper-and-pencil internet data collection methods. Psychological Methods, 187, 53–70.

Wood, R., McConnell, S., Moore, Q., Clarkwest, A., & Hsueh, J. (2010). The building strong families project: Strengthening unmarried parents’ relationships, the early impacts of building strong families. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Family Self-Sufficiency Research Consortium, Grant 90PD0278, funded by the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation in the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. We would like to acknowledge and thank Keith Chrzan from Sawtooth Software Inc. who programmed the best–worst scaling experiment and provided statistical analyses of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fabiano, G.A., Schatz, N.K. & Jerome, S. Parental Preferences for Early Intervention Programming Examined Using Best–Worst Scaling Methodology. Child Youth Care Forum 45, 655–673 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9348-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9348-z