Abstract

Purpose

The primary objectives in this review were to (1) assess the association between socioeconomic deprivation and survival in endometrial cancer patients (2) investigate if there is an association between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity in endometrial cancer patients.

Methods

We performed a systematic review using Medline (1946–2018), Embase (1980–2018), Cinahl (1981–2018) and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials to identify studies that reported on the association between socioeconomic deprivation and survival or peri-operative outcomes in endometrial cancer patients. Included were adult women (age ≥ 18 years) diagnosed with primary endometrial cancer. Two reviewers independently selected studies and assessed bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa assessment scale. Data extraction was completed using pre-determined forms, and summary tables of evidences from the included studies were created.

Results

Nine studies were included in this review with a total number of 369,900 patients. Eight studies investigated survival and socioeconomic deprivation, and the majority showed that socioeconomic deprivation is associated with poorer survival in endometrial cancer patients. One study assessed the association between deprivation and peri-operative morbidity and found no difference in 30-day postoperative mortality.

Conclusions

Socioeconomic deprivation seems to be associated with worse survival in endometrial cancer patients, even after adjusting for stage at diagnosis. However, the impacts of important confounders such as BMI, smoking and comorbidities are unclear and should be assessed. The relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity is unclear, and further research is needed to evaluate this aspect. A standardised measure for socioeconomic deprivation is needed in order to establish adequate comparison between studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the sixth most commonly occurring cancer in women, with over 380,000 estimated new cases worldwide and nearly 90,000 estimated deaths in 2018 [1]. Both incidence and mortality rates have increased over the last decades, with obesity being one of the main risk factors [2]. The increase in obesity has multiple underlying factors including socioeconomical factors, with a strong association between obesity and lower socioeconomic status (SES) in endometrial cancer patients and in the general population [3, 4].

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a measure of an individual’s economic and sociological standing and is based on income, education and occupation [5]. SES is considered to be an important predictor of health due to health inequalities [6]; however, the relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and cancer is complex and multifaceted. The incidence of various cancers including endometrial cancer is higher in deprived groups [7]. Furthermore, death rates are examined extensively and are shown to be higher among the most deprived for most types of cancer [8]. However, the relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and survival in endometrial cancer patients is not fully established.

Whilst Body Mass Index (BMI) is related to SES and obesity is associated with an increased risk of surgical morbidity in endometrial cancer patients [9], the relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity is unclear.

In this systematic review, our aim is to establish the relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and survival in endometrial cancer patients. In addition, we aim to investigate the correlation between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity.

Objectives

-

To evaluate the association between socioeconomic deprivation and survival in endometrial cancer patients.

-

To assess the correlation between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity in endometrial cancer patients.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to address the subject of socioeconomic deprivation and survival in endometrial cancer patients.

Eligibility criteria

We have used the following definition by Peter Townsend, sociologist, of socioeconomic deprivation: a lack of social and economic benefits which are considered to be basic necessities in a society [10]. We have included studies with individual, area-based or both types of measures of socioeconomic deprivation in this review.

The following criteria were used to exclude articles from further consideration: not in English, contained no original data, meeting abstract only (no full article for review) or article did not apply to any of the review questions. We furthermore excluded articles that used indirect measures of socioeconomic deprivation such as marriage or insurance status only.

Types of studies

We included all study designs evaluating the association between socioeconomic status and survival or peri-operative outcomes in endometrial cancer patients as a primary outcome.

Types of participants

-

Adult women (age ≥ 18 years) diagnosed with primary endometrial cancer.

Search strategy and selection criteria

This review was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and in accordance with the principles outlined in the Cochrane Handbook [11]. We performed systematic searches in Medline (1946 until May 2018), Embase (1980 until May 2018) and Cinahl (1981 until May 2018) and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials. Search strategies were adapted accordingly to each database. The used search strategies are presented in Appendix 1. In addition, we searched grey literature including abstracts of scientific meetings as well as manually checking the reference lists of eligible studies to identify any additional studies to include in this review.

Types of outcome measures

-

Primary outcomes Survival including overall survival (OS), cause-specific survival (CSS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS).

-

Secondary outcomes Peri-operative morbidity in terms of peri-operative complications (intra-operative complications including nerve injury, bowel injury, bladder injury, ureter injury and vascular injury and postoperative complications including wound problems, fascia dehiscence, ileus, urinary tract infection, haemorrhage, pneumonia, pelvic abscess, haematoma, venous thromboembolism, sepsis, renal complications, cardiac complication and organ failure) and 30-day mortality.

Study selection

Two reviewers (HD and KG) independently assessed titles and abstracts of all identified studies. Those studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full text and were further reviewed for eligibility by both reviewers.

Data extraction

Data extraction was completed by two of the authors (HD and KG) using pre-determined forms which included study author names, publication dates, study designs, sample sizes, measures of socioeconomic deprivation, results of univariate analyses testing for zero-order association between socioeconomic deprivation and survival or peri-operative outcomes and the results of the multivariate analyses testing for association between socioeconomic deprivation and survival or peri-operative outcomes adjusting for control variables. Differences were resolved by consensus.

Assessment of risk bias

The risk of bias included in studies was assessed by two authors (HD and KG) independently using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Form for Cohort Studies which includes selection, comparability and outcome [12]. Differences were resolved by consensus.

Data synthesis

We were unable to conduct a meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity in the included studies. However, we created summary tables of evidence from the included studies and then examined the relationship between various measures of socioeconomic deprivation and outcomes across studies.

Results

Study selection

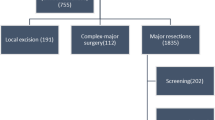

The search strategy identified 127 references in Medline, 183 in Embase and 35 in Cinahl. Search results were merged, and duplicates were removed, resulting in 247 unique studies. After screening title and abstract, 16 articles were retrieved in full text and were further assessed for eligibility. Subsequently seven studies were considered eligible for this review, and a further search of the grey literature identified two articles, resulting in the inclusion of nine articles in this review (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the nine studies included in this review are illustrated in Table 1. All studies combined resulted in a total of 369,900 endometrial cancer patients, and all studies were of retrospective design. Eight studies included all stages of endometrial cancer, whereas one study only included stages I to II endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Different measures of socioeconomic deprivation were used: income, level of education, unemployment, social class, housing tenure and insurance status. Furthermore, two studies used the Income Domain of the English Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), which are published by the UK Department for Communities and Local Government and measure a spectrum of deprivation [13].

Risk of bias of included studies

We have assessed the risk of bias with the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Two studies were of poor quality, and seven studies were of good quality (see Fig. 2).

Synthesis of results

Socioeconomic deprivation and survival

Eight studies with 331,568 endometrial cancer patients assessed survival and socioeconomic deprivation, see Table 1. A study done by The National Cancer Intelligence Network (NCIN) used the income domain of IMD and showed a relationship between deprivation and mortality in England, with a higher mortality rate in the more income-deprived groups [14]. However, they did not adjust for any confounders.

Furthermore, three studies [15,16,17] used the median household income as a measure of SES of which two studies (Madison et al. and Robbins et al.) found an association between mortality and deprivation, with a higher income being associated with a decreased risk of death [15, 16]. However, in a multivariate analysis, Robbins et al. did not identify SES as a significant predictor of patient outcome, while in the study done by Madison et al., the significance remains after adjusting for stage. The third study done by Fader et al. [17] found no difference either in overall survival or recurrence-free survival within the different income groups or educational levels, even after adjusting for stage.

The study done by Cheung et al. [18] looked at county-level family income and found a decreased survival in patients living in low-income neighbourhood, which did not remain significant in multivariate analysis, while a study done by Ueda et al. [19] used municipality-based SES and found poorer 5-year survival in the low unemployment and education municipalities, even after adjusting for stage. The study done by Jensen et al. [20] used six different socioeconomic indicators and found no strong association between socioeconomic variables and survival, but survival tended to be better for women with higher education and more disposable income; however, they did not correct for confounders. Lastly, a study done by Seidelin et al. [21] showed education to be associated with higher hazard ratio (HR) for death, even after adjusting for confounders such as stage at diagnosis, BMI and comorbidities.

Socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity

A study done by Gildea et al. [22] used the income domain of the English IMD to assess the relationship between postoperative mortality and deprivation, and found no association between income deprivation and 30-day postoperative mortality. No other articles were found, which investigated the association between deprivation and peri-operative morbidity in endometrial cancer patients.

Discussion

This review summarises the current literature about the association between socioeconomic deprivation and survival in endometrial cancer patients. The results of this systematic review suggest a worse survival for more socioeconomically deprived patients, with six studies showing low SES being associated with worse survival in univariate analysis, and three studies confirming poor outcome in multivariate analysis. However, two studies did not show an association.

Previous research has looked at possible explanations for the differences in cancer survival within different groups of deprivation, with stage at diagnosis being one of the most important factors [23]. In cervical, breast and colorectal cancer these survival differences are related to the differences in participation rate in cancer screening programmes, in which women with lower SES and women living in urban areas are less likely to participate [24]. For endometrial cancer, there is no routine screening; however, since patients present early with bleeding problems, it is usually diagnosed at an early stage, which leads to high survival rates [14]. This suggests that SES impacts survival in endometrial cancer through other factors which may include BMI, age, smoking and comorbidities.

For endometrial cancer, factors that are associated with advanced stage at diagnosis include high-grade lesions, serous histologic subtype, older age and low SES [21, 25, 26]. Patients with higher socioeconomic position might be more aware of symptoms and present quicker to a general practitioner or medical specialist, while low-SES patients tend to ignore early symptoms of disease such as postmenopausal bleeding [21]. This could partially explain the differences in survival; however, most studies included in this review with the exception of two (Jensen et al. and NCIN) corrected for stage at diagnosis in their analyses. Therefore, it seems that regardless of stage at diagnosis, socioeconomic deprivation affects survival in endometrial cancer patients.

Other important factors in cancer survival in general and in endometrial cancer patients include BMI, with normal-weight women having better survival than obese patients [23, 27]. One of the mechanisms that has been suggested to explain the differences in survival is the fact that obesity is associated with an increased risk of surgical morbidity [9]; however, some studies have shown that it is not an independent predictor but likely related to other comorbid conditions [28]. Since there is a strong relationship between obesity and socioeconomic deprivation in endometrial cancer patients [4], this could potentially be an important factor affecting survival in deprived patients; however, the articles included in this review, with the exception of Seidelin et al., did not include or correct for BMI.

A third factor in cancer survival is comorbidity, previous research has shown a decreased survival for endometrial cancer patients with multiple comorbidities [29]. Different reasons are reported such as delayed diagnosis, higher rate of postoperative complications, a reduction of the possibility of surgery and a lower tolerance of oncological treatment [30]. Since the prevalence of comorbidity tend to be higher among endometrial cancer patients with higher levels of deprivation [31], this could also affect survival. Of the articles included in this review, only Seidelin et al. corrected for comorbidity and found no difference in the odds ratio for death.

Furthermore age at diagnosis is an important factor in endometrial cancer survival [32]. Elderly patients often have more aggressive histology and are less likely to receive surgical treatment or adjuvant therapy leading to under treatment [33]. Furthermore an article by Poupon et al. [33] showed 3-year OS rates to be lower than cancer specific survival rate, indicating that death in elderly is often a combination of death due to cancer as well as to causes other than cancer. All studies included in this review have adjusted for age at diagnosis with the exemption of Cheung et al. [18].

Another element in survival in endometrial cancer is treatment received by patients [34]. This is often influenced by patient characteristics such as age, comorbidities and patient preference. Furthermore, the type of treatment centre (cancer centre or smaller hospital) also influences the type of treatment offered to patients and influences survival in endometrial cancer patients [35, 36]. Patients with low SES are less likely to afford travel costs to cancer centres, especially if they reside in rural counties. Only half of the studies included in this review have taken treatment into account.

Lastly, smoking status is an important aspect in survival in endometrial cancer, in which smokers show worse survival compared to non-smokers [37], although some of the overall survival differences may be more attributable to associated comorbid conditions in smokers. None of the studies in this review have corrected for smoking status in their analysis.

BMI, comorbidities and smoking not only affect survival, but are also risk factors for peri-operative morbidity in endometrial cancer patients [9, 38, 39]. Because of the correlation of SES with BMI, comorbidities and smoking status, we have tried to investigate if there is a relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity; however, the current literature is scarce, and only one study was identified which did not show any association between income deprivation and 30-day postoperative mortality [22]. Further research is needed to establish any relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity including 30-day mortality in endometrial cancer patients.

The studies in this review have used different measures of mortality (age-standardised mortality rate, survival time, disease-specific survival, overall survival, 1- and 5-year survival, etc.), which is an important issue when comparing results. Endometrial cancer has a relatively high survival rate; however, the one-year survival will be very different to mortality rates and may reflect the individual’s underlying comorbidities which may lead to earlier demise. Therefore, it is difficult to compare all different measures of mortality.

Despite increasing recognition of the impact of socioeconomic deprivation on survival of endometrial cancer patients, questions about the strength of its impact and relationship with other prognostic factors remain. To address these questions, more studies are needed which measure socioeconomic deprivation with a standardised measure and also correct for other prognostic variables including BMI, comorbidities and smoking status. From this knowledge, interventions to improve survival in lower SES patients can then be introduced.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The majority of women were diagnosed with stage I disease, consistent with reported incidence rates [40]. Literature was scarce about the correlation between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity and we only found one study that evaluated peri-operative outcomes and SES in endometrial cancer patients.

Quality of evidence

The studies included were of a high degree of heterogeneity in study design and evaluated a variety of socioeconomic status measures, which lacked in uniformity. Different measures were used, each capturing a distinct aspect of SES, which may be correlated with other measures, but are not interchangeable [41]. Furthermore, individual SES measures such as income and occupation differ from environmental SES measures, which are area-based, and these two measures often do not correlate well [42]. These different measures can all impact results. Area-based measures may not accurately represent a patient’s socioeconomic deprivation status, since not all people living in low income are poor themselves. Furthermore, there is a large variety in definitions of socioeconomic deprivation: the definition of a deprived person living in the United States might be different from a deprived person living in Japan. In addition, in some studies, only one indicator of SES was used, while others used multiple measures. Furthermore, most studies have not adjusted for important confounders. Therefore, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the strength of the evidence.

Potential biases in review process

A comprehensive search of the literature with aid of librarian was performed by two reviewers independently, including a search of the grey literature. Reviewers assessed potentially eligible articles independently and discussed the differences found.

Comparison with the existing literature

A previous review done by Kogevinas et al. [8] about socioeconomic differences in cancer survival included six studies about endometrial cancer and showed survival was poorest in low socioeconomic groups in five studies; in three of those studies, differences were statistically significant. However, the reverse pattern was seen in one study. The association of inequality in survival is supported by several studies that have assessed the association between SES and cancer survival in general and that also included endometrial cancer patients [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53], even though several other studies did not find any association between deprivation and mortality [54,55,56,57,58].

Conclusion

Socioeconomic deprivation seems to be associated with poorer survival in endometrial cancer patients, regardless of their stage at diagnosis. However, important confounders such as BMI, comorbidities and smoking status should be taken into account. The relationship between peri-operative morbidity and socioeconomic deprivation is not clear.

Implications for clinical practice

-

Socioeconomic deprivation status should be included in the initial evaluation of new patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer.

-

Early and non-invasive diagnostic testing is needed in the community to improve access to health care in deprived groups.

-

Early referral to cancer support teams is recommended.

Implications for research

-

Further research should be directed to establish any relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and peri-operative morbidity in endometrial cancer patients.

-

Furthermore, a standardised measure for socioeconomic deprivation is needed in order to establish adequate comparison between studies.

-

Further studies should adjust for important confounders such as BMI, comorbidities and smoking to assess the true extent of socioeconomic deprivation on survival in endometrial cancer patients.

References

Bray F et al (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 00:1–31

Friedenreich C et al (2007) Anthropometric factors and risk of endometrial cancer: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Causes Control 18(4):399–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0113-8

McLaren L (2007) Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxm001

Ross J, Escamilla V, Lee N, Yamada S, Lindau S (2017) Endometrial cancer survivors’ access to recommended self-care resources to target obesity in a high poverty urban community. Gynecol Oncol 145:27–28

Mueller CW, Parcel TL (1981) Measures of socioeconomic status: alternatives and recommendations. Child Dev 52:13–30

Marmot MG, Kogevinas M, Elston MA (1987) Social/economic status. Annu Rev Public Health 8:111–135

Marmot M (2006) Cancer and health inequalities : an introduction to current evidence. 40

Kogevinas M, Porta M (1997) Socioeconomic differences in cancer survival: a review of the evidence. IARC Sci Publ (138):177–206

Bouwman F et al (2015) The impact of BMI on surgical complications and outcomes in endometrial cancer surgery—an institutional study and systematic review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 139:369–376

Townsend P, Alastair B (1988) Health and deprivation: inequality and the North. Routledge, Abingdon

Higgins JP, Green S (2008) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184

Wells GA et al (2013) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hosp Res Inst. https://doi.org/10.2307/632432

Department for Communities and Local Government (2015) The English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2015. English Index Mult. Deprivation 2015 Infographic

NCIN (2013) Outline of uterine cancer in the United Kingdom: incidence, mortality and survival

Madison T, Schottenfeld D, James SA, Schwartz AG, Gruber SB (2004) Endometrial cancer: socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Am J Public Health 94:2104–2111

Robbins JR, Mahan MG, Krajenta RJ, Munkarah AR, Elshaikh MA (2013) The impact of income on clinical outcomes in FIGO stages i to II endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus. Am J Clin Oncol Cancer Clin Trials 36:625–629

Fader AN et al (2016) Disparities in treatment and survival for women with endometrial cancer: a contemporary national cancer database registry analysis. Gynecol Oncol 143:98–104

Cheung M (2013) African American Race and low income neighborhoods SEER analysis. Asian Pacific J Cancer 14:2567–2570

Ueda K, Kawachi I, Tsukuma H (2006) Cervical and corpus cancer survival disparities by socioeconomic status in a metropolitan area of Japan. Cancer Sci 97:283–291

Jensen KE et al (2008) Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancer of the female genital organs in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer 44:2003–2017

Seidelin UH et al (2016) Does stage of cancer, comorbidity or lifestyle factors explain educational differences in survival after endometrial cancer? A cohort study among Danish women diagnosed 2005–2009. Acta Oncol (Madr) 55:680–685

Gildea C, Nordin A, Hirschowitz L, Poole J (2016) Thirty-day postoperative mortality for endometrial carcinoma in England: a population-based study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 123:1853–1861

Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP (2006) Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: a review. Ann Oncol 17:5–19

Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T (2005) Reduced likelihood of cancer screening among women in urban areas and with low socio-economic status: a multilevel analysis in Japan. Public Health 119:875–884

Barrett RJ et al (1995) Endometrial cancer: stage at diagnosis and associated factors in black and white patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173:414–423

Madison T, Schottenfeld D, James SA, Schwartz AG, Gruber SB (2004) Endometrial cancer: socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Am J Public Health 94:2104–2111

Arem H, Irwin M (2013) Obesity and endometrial cancer survival: a systematic review. Int J Obes 37:634–639

Temkin SM, Pezzullo JC, Hellmann M, Lee Y (2007) Is body mass index an independent risk factor of survival among patients with endometrial cancer? Am J Clin Oncol 30:8–14

Binder PS et al (2017) Adult comorbidity evaluation 27 score as a predictor of survival in endometrial cancer patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 215:1–17

Søgaard M, Thomsen RW, Bossen KS, Sørensen HT, Nørgaard M (2013) The impact of comorbidity on cancer survival: a review. Clin Epidemiol 5:3–29

Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C (2016) The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatments. CA Cancer J Clin 00:1–13

Huang C et al (2012) Nationwide surveillance in uterine cancer: survival analysis and the importance of birth cohort: 30-year population-based registry in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 7:1–10

Poupon C et al (2017) Management and survival of elderly and very elderly patients with endometrial cancer: an age-stratified study of 1228 women from the FRANCOGYN Group. Ann Surg Oncol 24:1667–1676

Lee YC, Lheureux S, Oza AM (2017) Treatment strategies for endometrial cancer: current practice and perspective. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 29:47–58

Zahnd WE et al (2018) Rural–urban differences in surgical treatment, regional lymph node examination, and survival in endometrial cancer patients. Cancer Causes Control 29:221–232

Hashibe M et al (2018) Disparities in cancer survival and incidence by metropolitan versus rural residence in Utah. Cancer Med 7:1490–1497

Modesitt SC, Huang B, Shelton BJ, Wyatt S (2006) Endometrial cancer in Kentucky: the impact of age, smoking status, and rural residence. Gynecol Oncol 103:300–306

Tozzi R, Malur S, Koehler C, Schneider A (2005) Analysis of morbidity in patients with endometrial cancer: is there a commitment to offer laparoscopy? Gynecol Oncol 97:4–9

Bakkum-Gamez JN et al (2014) Predictors and costs of surgical site infections in patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 130:100–106

Creasman WT et al (2003) Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. Int J Gynecol Obstet 83:79–118

Shavers VL (2007) Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc 99:1013–1023

Demissie K, Hanley JA, Menzies D, Joseph L, Ernst P (2000) Agreement in measuring socio-economic status: area-based versus individual measures. Chronic Dis, Can

Schrijvers CTM, Mackenbach JP, Lutz J, Quinn MJ, Coleman MP (1995) Deprivation, stage at diagnosis and cancer survival. Int J Cancer 63:324–329

Chien LH et al (2018) Patterns of age-specific socioeconomic inequalities in net survival for common cancers in Taiwan, a country with universal health coverage. Cancer Epidemiol 53:42–48

Exarchakou A, Rachet B, Belot A, Maringe C, Coleman MP (2018) Impact of national cancer policies on cancer survival trends and socioeconomic inequalities in England, 1996–2013: population based study. Bmj. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k764

Jeffreys M et al (2009) Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in New Zealand: the role of extent of disease at diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18:915–921

Stanbury JF, Baade PD, Yu Y, Yu XQ (2016) Cancer survival in New South Wales, Australia: socioeconomic disparities remain despite overall improvements. BMC Cancer 16:48

Greenwald HP, Polissar NL, Dayal HH (1996) Race, socioeconomic status and survival in three female cancers. Ethn Health 1:65–75

Coleman MP, Babb P, Sloggett A, Quinn M, De Stavola B (2001) Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in England and Wales. Cancer 91:208–216

Ito Y et al (2014) Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival: a population-based study of adult patients diagnosed in Osaka, Japan, during the period 1993–2004. Acta Oncol (Madr) 53:1423–1433

Dalton SO et al (2008) Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003: summary of findings. Eur J Cancer 44:2074–2085

Auvinen A, Karjalainen S, Pukkala E (1995) Social class and cancer patient survival in Finland. Am J Epidemiol 142:1089–1102

Faggiano F, Lemma P, Costa G, Gnavi R (1995) Cancer mortality by educational level in Italy. Cancer Causes Control 6:311–320

Eberle A, Luttman S, Foraita R, Pohlabeln H (2010) Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality—a spatial analysis in Bremen. J Public Health 18:227–235

Jansen L et al (2014) Socioeconomic deprivation and cancer survival in Germany: an ecological analysis in 200 districts in Germany. Int J Cancer 134:2951–2960

Yu XQ, O’Connell DL, Gibberd RW, Armstrong BK (2008) Assessing the impact of socio-economic status on cancer survival in New South Wales, Australia 1996–2001. Cancer Causes Control 19:1383–1390

Rosso S, Faggiano F, Zanetti R, Costa G (1997) Social class and cancer survival in Turin, Italy. J Epidemiol Community Health 51:30–34

Sloggett A, Young H, Grundy E (2007) The association of cancer survival with four socioeconomic indicators: a longitudinal study of the older population of England and Wales 1981–2000. BMC Cancer 7:1–8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HD designed the study, performed the systematic search, assessed eligibility of the articles and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. RB and LM contributed to the design of the study and edited the manuscript. KG designed the study, assessed eligibility of the articles, edited and wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

(i) We declare that the contents of this paper have not been published or considered for publication elsewhere. (ii) All authors made substantial contribution to conception and design, and/or acquisition of data and/or analysis and interpretation of data; participated in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and gave final approval of the version to be submitted and any revised version to be published. (iii) There is no financial support or relationship that may pose any conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Donkers, H., Bekkers, R., Massuger, L. et al. Systematic review on socioeconomic deprivation and survival in endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control 30, 1013–1022 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01202-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01202-1