Abstract

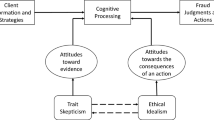

The objective of this study is to evaluate auditors’ perceived responsibility for fraud detection. Auditors play a critical role in managing fraud risk within organizations. Although professional standards and guidance prescribe responsibility in the area, little is known about auditors’ sense of responsibility for fraud detection, the factors affecting perceived responsibility, and how responsibility affects auditor performance. We use the triangle model of responsibility as a theoretical basis for examining responsibility and the effects of accountability, fraud type, and auditor type on auditors’ perceived fraud detection responsibility. We also test how perceived responsibility affects auditor brainstorming performance given the importance of brainstorming in audits. A sample of 878 auditors (241 external auditors and 637 internal auditors) participated in an experiment with accountability pressure and fraud type manipulated randomly between subjects. As predicted, accountable auditors report higher detection responsibility than anonymous auditors. We also find a significant fraud type × auditor type interaction with external auditors perceiving the most detection responsibility for financial statement fraud, while internal auditors report similar detection responsibility for all fraud types. Analysis of the triangle model’s formative links reveals that professional obligation and personal control are significantly related to responsibility, while task clarity is not. Finally, the results indicate that perceived responsibility positively affects the number of detection procedures brainstormed and partially mediates the significant accountability–brainstorming relation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The governance literature (e.g., Adamec et al. 2005; Lapides et al. 2007; Rossiter 2011) describes management, the board of directors, external auditors, and internal auditors as four “pillars” of governance and suggests that the occurrence of fraud provides evidence of failures among these primary governance mechanisms (CAQ 2010; IIA et al. 2008; Kochan 2002).

Balkaran (2008) distinguishes external auditing and internal auditing by noting that external auditors are not part of the organizations they audit, but are instead engaged by them, while internal auditors are “integral” parts of their organization serving management and the board of directors as clients.

The professional (e.g., ACFE 2014; AICPA 2009), research (Alleyne and Elson 2013; Hunt 2014), and education (e.g., Albrecht et al. 2016; Girgenti and Hedley 2011; Wells 2014) literature typically describe financial statement fraud, asset misappropriation, and corruption as the three primary types of fraud. The ACFE (2014) reports that misappropriation of assets is involved in 87 % of cases, corruption in 33 % of cases, and financial statement fraud 8 % of cases. However, the ACFE also finds that the median loss in financial statement fraud cases is $1 million, compared to $250,000 for corruption cases and $120,000 for asset misappropriation cases.

The literature provides a variety of definitions of accountability in a variety of contexts (e.g., Bovens 2007; Brandsma and Schillemans 2012; DeZoort et al. 2006; Tetlock 1985, 1992). The Schlenker definition of accountability as an antecedent social pressure construct is consistent with alternative definitions of accountability in individual judgment and decision-making studies.

For example, the extant literature provides evidence that auditor brainstorming quality is affected by the quality of brainstorming guidance used (Trotman et al. 2009), the use of face-to-face sessions (Carpenter 2007), and documentation specificity (Hammersley et al. 2010). Brazel et al. (2010) find that brainstorming quality is linked to a number of process variables, including use of an audit partner or forensic specialist to lead the brainstorming session, attendance by an information technology specialist, and early timing of brainstorming in the audit process.

The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) (2009) defines professional skepticism as “an attitude that includes a questioning mind and a critical assessment of audit evidence” (p. 13).

The study and all research materials also were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the researchers’ universities. The materials were developed in consultation with groups of accounting and psychology researchers to ensure case realism, understandability, and content validity for the framework’s measurement items. We also pretested the materials with 114 undergraduate and graduate accounting students. The development and pretest procedures led to minor modifications to the instrument.

Nelson et al. (2003) reviewed 515 earnings management efforts reported by auditors and found that 31 % of attempts reported were income-decreasing.

Beasley and Jenkins (2003) describe open brainstorming as a very unstructured approach where individuals can identify ideas freely with very few rules and procedures to impede the process.

The study’s primary results are not affected by including participants who missed at least one manipulation check question.

References

Adamec, B., Leinkicke, L., Ostrosky, J., & Rexroad, W. (2005). Getting a leg up. Internal Auditor, 62(3), 40–45.

Adamson, E., Hybnerova, K., Esmark, C., and Noble, S. (2014). A tangled web: Views of deception from the customer’s perspective. Business Ethics: A European Review, doi: 10.1111/beer.12068.

AICPA. (2009). The guide to investigating business fraud. New York, NY: AICPA.

Albrecht, S., Albrecht, C., Albrecht, C., & Zimbelman, M. (2016). Fraud examination (5e). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Albrecht, C., Holland, D., Malagueno, R., Dolan, S., & Tzafrir, S. (2014). The role of power in financial statement fraud schemes. Journal of Business Ethics,. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-2019-1.

Alleyne, B., & Elson, R. (2013). The impact of federal regulations on identifying, preventing, and eliminating corporate fraud. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 16, 91–106.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (1988). Illegal acts by clients., Statement on Auditing Standards No. 54 New York, NY: AICPA.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (1997). Responsibilities and Functions of the Independent Auditor., Statement on Auditing Standards No. 1 New York, NY: AICPA.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2002). Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit., Statement on Auditing Standards No. 99 New York, NY: AICPA.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2005). The AICPA Audit Committee Toolkit. New York, NY: AICPA.

Anand, V., Dacin, M., & Murphy, P. (2014). The continued need for diversity in fraud research. Journal of Business Ethics,. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2494-z.

Aranya, N., & Ferris, K. (1984). A reexamination of accountants’ organizational-professional conflict. The Accounting Review, 60, 1–15.

Asare, S., & Wright, A. (2004). The effectiveness of alternative risk assessment and program planning tools in a fraud setting. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21, 325–352.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, (ACFE). (2010). ACFE report to the nations on occupational fraud and abuse. Austin, TX: ACFE.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, (ACFE). (2014). ACFE report to the nations on occupational fraud and abuse. Austin, TX: ACFE.

Balkaran, L. (2008). Two sides of auditing: Despite their obvious similarities, internal auditing and external auditing have an array of differences that make them distinctly valuable. Internal Auditor, 65(5), 21–23.

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beasley, M., & Hermanson, D. (2004). Going beyond Sarbanes-Oxley compliance: Five keys to creating value. The CPA Journal, 74(6), 11–13.

Beasley, M., & Jenkins, G. (2003). A primer for brainstorming fraud risks. Journal of Accountancy, 196(6), 32–38.

Bobek, D., Hageman, A., & Radtke, R. (2010). The ethical environment of tax professionals: Partner, and non-partner perceptions and experiences. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 637–654.

Bobek, D., Hageman, A., & Radtke, R. (2013). The influence of roles and organizational fit on accounting professionals’ perceptions of their firms’ ethical environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(1), 1–17.

Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468.

Boyle, D., DeZoort, T., & Hermanson, D. (2015). The effect of alternative fraud model use on auditors’ fraud risk judgments. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34, 578–596.

Brandsma, G and Schillemans, T. (2012). The accountability cube: Measuring accountability. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 1–23.

Braun, R. (2000). The effect of time pressure on auditor attention to qualitative aspects of misstatements indicative of potential fraudulent financial reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25, 243–259.

Brazel, J. F., Carpenter, T. D., & Jenkins, J. G. (2010). Auditors’ use of brainstorming in the consideration of fraud: Reports from the field. The Accounting Review, 85, 1273–1302.

Buchman, T., Tetlock, P., & Reed, R. (1996). Accountability and auditors’ judgment about contingent events. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 23, 379–398.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81–105.

Carpenter, T. D. (2007). Audit team brainstorming, fraud risk identification, and fraud risk assessment: Implications of SAS No. 99. The Accounting Review, 82, 1119–1140.

Carpenter, T., Reimers, J., & Fretwell, P. (2011). Internal auditors’ fraud judgments: The benefits of brainstorming in groups. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(3), 211–224.

Carver, C. (1979). A cybernetic model of self-attention processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1251–1281.

Case, D. (2006). Looking for information: A survey of research on Information seeking, needs, and behavior. Amsterdam: Academic Press.

Center for Audit Quality. (2010). Deterring and detecting financial reporting fraud: A platform for action. Washington, DC: Center for Audit Quality.

Center for Audit Quality, Financial Executives International, The Institute of Internal Auditors, and National Association of Corporate Directors. (2013). Closing the expectations gap in deterring and detecting financial statement fraud: A roundtable summary. Washington, DC: Center for Audit Quality.

Chang, C., Ho, J., & Liao, W. (1997). The effects of justification, task complexity and experience/training on problem-solving performance. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 9(Supplement), 98–116.

Christopher, A., & Schlenker, B. (2005). The protestant work ethic and attributions of responsibility: Applications of the triangle model. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(7), 1502–1518.

Cloyd, C. (1997). Performance in tax research tasks: The joint effects of knowledge and accountability. The Accounting Review, 72, 111–132.

Cohen, J., Ding, Y., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2010). Corporate fraud and managers’ behavior: Evidence from the press. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(Supplement), 271–315.

Cuccia, A., Hackenbrack, D., & Nelson, M. (1995). The ability of professional standards to mitigate aggressive reporting. The Accounting Review, 70, 227–248.

Davis, B., Read, D., & Powell, S. (2014). Exploring employee misconduct in the workplace: Individual, organizational, and opportunity factors. Journal of Academic and Business Ethics, 8, 1–12.

Deloitte. (2012). The changing role of internal audit. New York, NY: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu.

DeZoort, F. T., Harrison, P. D., & Schnee, E. J. (2012). Tax professionals’ responsibility for fraud detection: The effects of engagement type and audit status. Accounting Horizons, 26, 289–306.

DeZoort, T., & Lord, A. (1994). An investigation of obedience pressure effects on auditors’ judgments. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 6, 1–30.

DeZoort, F. T., Harrison, P., & Taylor, M. H. (2006). Accountability and auditors materiality judgments: The effects of differential pressure strength on conservatism, variability, and effort. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31, 373–390.

Eagly, A., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Eining, M., Jones, D., & Loebbecke, J. (1997). Reliance on decision aids: An examination of auditors’ assessment of management fraud. Auditing: A Journal of Practice Theory, 16, 1–19.

Enyon, G., Hills, N., & Stevens, K. (1997). Factors that influence the moral reasoning abilities of accountants: Implications for universities and the profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(12/13), 1297–1309.

Firth, M., Mo, P., & Wong, R. (2005). Financial statement fraud and auditor sanctions: An analysis of enforcement actions in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 62, 367–381.

Girgenti, R., & Hedley, T. (2011). Managing the risk of fraud and misconduct. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Co.

Glover, S., Prawitt, D., & Zimbelman, M. (2003). A test of changes in auditors’ fraud-related planning judgments since the issuance of SAS No. 82. Auditing: A Journal of Practice Theory, 22, 237–251.

Greer, L., & Tonge, A. (2006). Ethical foundations: A new framework for reliable financial reporting. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(3), 259–270.

Hackenbrack, K., & Nelson, M. (1996). Auditors’ incentives and their applications of financial accounting standards. The Accounting Review, 71, 43–59.

Hagenbaugh, R. (2005). Fraud risk assessments’ place in ERM. CSA Sentinel, 9(3), 3–6.

Hammersley, J. S., Bamber, E. M., & Carpenter, T. D. (2010). The influence of documentation specificity and priming on auditors’ fraud risk assessments and evidence evaluation decisions. The Accounting Review, 85(2), 547–571.

Haynes, C., Jenkins, G., & Nutt, S. (1998). The relationship between client advocacy and audit experience: An exploratory analysis. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 17, 88–104.

Hedley, T., Porco, B., & Littley, J. (2011). Detection: Auditing and monitoring. In R. Girgenti & T. Hedley (Eds.), Managing the risk of fraud and misconduct (pp. 211–224). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hoffman, V., & Patton, J. (1997). Accountability, the dilution effect, and conservatism in auditors’ fraud judgments. Journal of Accounting Research, 35, 227–238.

Hoffman, V. B., & Zimbelman, M. F. (2009). Do strategic reasoning and brainstorming help auditors change their standard audit procedures in response to fraud risk? The Accounting Review., 84, 811–838.

Hunt, G. (2014). A descriptive comparison of two sources of occupational fraud data. Journal of Business & Economic Research, 12, 171–176.

IIA, Aicpa, & ACFE. (2008). Managing the business risk of fraud: A practical guide. Altamonte Springs, FL: The IIA.

Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). (2009). Internal auditing and fraud. IPPF practice guide. Altamonte Springs, FL: The IIA.

Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). (2011). The international standards for the professional practice of internal auditing. Altamonte Springs, FL: The IIA.

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (2009a): The Auditor’s Responsibilities Relating to Fraud in an Audit of Financial Statements. International Standards on Auditing No. 240. New York: NY: IFAC.

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (2009b). Consideration of Laws and Regulations in an Audit of Financial Statements. International Standards on Auditing No. 250. New York: NY: IFAC.

Jamnik, A. (2011). Ethical code in the public accounting profession. Journal of International Business Ethics, 4, 17–29.

Joe, J. (2003). Why press coverage of a client influences the audit opinion. Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 109–133.

Joe, J., & Vandervelde, S. (2007). Do auditor-provided nonaudit services improve audit effectiveness? Contemporary Accounting Research, 24, 467–487.

Kennedy, J. (1993). Debiasing audit judgments with accountability: A framework and experimental results. Journal of Accounting Research, 31, 231–245.

Kerler, W., & Killough, L. (2009). The effects of satisfaction with a client’s management during a prior audit engagement, trust, and moral reasoning on auditors’ perceived risk of management fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 109–136.

Knapp, C., & Knapp, M. (2001). The effects of experience and explicit fraud risk assessment in detecting fraud with analytical procedures. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26, 25–37.

Kochan, T. A. (2002). Addressing the crisis in confidence in corporations: Root causes, victims, and strategies for reform. Academy of Management Executive, 16(3), 139–141.

Kohns, J. W., & Ponton, M. K. (2006). Understanding responsibility: A self-directed learning application of the triangle model of responsibility. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 20(4), 16–27.

KPMG. (2003). KPMG fraud survey 2003. Montvale, NJ: KPMG.

Lapides, P., Beasley, M., Carcello, J., DeZoort, T., Hermanson, D., Neal, T., and Tompkins, J. (2007). 21 st Century Governance and Audit Committee Principles. Corporate Governance Center, Kennesaw State University.

Lee, G., & Fargher, G. (2013). Companies’ use of whistle-blowing to detect fraud: An examination of corporate whistle-blowing policies. Journal of Business Ethics, 114, 283–295.

Lynch, A. (2006). Think like the fraudster: Brainstorming how fraudulent activities may occur can open the auditor’s mind to a host of new possibilities. Internal Auditor, 63(1), 66–71.

Marks, N. (2013). Should internal audit be responsible for detecting fraud. Internal Auditor, July 20, www.theiia.org.

Nelson, M., Elliott, J., & Tarpley, R. (2003). How are earnings managed? Examples from auditors. Accounting Horizons, 17(Supplement), 17–35.

Norman, C., Rose, A., & Rose, J. (2010). Internal audit reporting lines, fraud risk decomposition, and assessments of fraud risk. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35, 546–557.

Palmrose, Z.V. (2007). Statement by SEC Staff: SEC’s Proposed Interpretive Guidance to Management for Section 404 of Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Deputy Chief Accountant U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. SEC Open Meeting Washington, D.C. May 23, 2007.

Plous, S. (1993). The psychology of judgment and decision making. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ponemon, L. (1990). Ethical judgments in accounting: A cognitive-developmental perspective. Critical Perspectives in Accounting, 1, 191–215.

Porter, L., Steers, R., Mowday, R., & Boulian, P. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 603–609.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). (2004). The emerging role of internal audit in mitigating fraud and reputation risks. New York, NY: PwC, LLP.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). (2010). A future rich in opportunity: Internal audit must seize opportunities to enhance its relevancy. New York, NY: PwC, LLP.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). (2014). Global economic crime survey 2014. New York, NY: PwC, LLP.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). (2012). Maintaining and Applying Professional Skepticism in Audits. Staff Audit Practice Alert No. 10. Washington, D.C.: PCAOB.

Ramos, M. (2004). Fraud detection in a GAAS audit. New York, NY: AICPA.

Robinson, S., Robertson, J., & Curtis, M. (2012). The effects of contextual and wrongdoing attributes on organizational employees' whistleblowing intentions following fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 106, 213–227.

Rossiter, C. (2011). How internal audit adds value to the governance process, KnowledgeLeader. Menlo Park, CA: Protiviti Inc.

Schlenker, B. (1997). Personal responsibility: Applications of the triangle model. Research in Organizational Behavior, 19, 241–301.

Schlenker, B., Britt, T., Pennington, J., Murphy, R., & Doherty, K. (1994). The triangle model of responsibility. Psychological Review, 101, 632–652.

Schlenker, B., & Leary, M. (1982). Social anxiety and self-presentation: a conceptualization and model. Psychological Bulletin, 92, 641–669.

Shaub, M. (1994). An analysis of factors affecting the cognitive moral development of accountants and auditing students. Journal of Accounting Education, 12(1), 1–26.

Shelton, S., Whittington, R., & Landsittel, D. (2001). Auditing firms’ fraud risk assessment practices. Accounting Horizons, 15, 19–33.

Soltani, B. (2014). The anatomy of corporate fraud: A comparative analysis of high profile American and European corporate scandals. Journal of Business Ethics, 120, 251–274.

Spector, P. (1988). Development of work locus of control scale. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61, 335–340.

Tabuena, J. (2013). Auditor regulators: Embrace your inner skepticism. Compliance Week, 36–37.

Taylor, S., & Fiske, S. (1978). Salience, attention, and attribution: Top of the head phenomena. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 11). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Tetlock, P. (1985). Accountability: the neglected social context of judgment and choice. In B. Staw & L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Tetlock, P. (1992). The impact of accountability on judgment and choice: Toward a social contingency model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 331–376.

Thorne, L., Massey, D., & Magnan, M. (2003). Institutional context and auditors’ moral reasoning: A Canada-USA comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(4), 305–321.

Tie, R. (2011). The GRC toolbox: The use of integrated methods to fight fraud. Fraud Magazine, 38–43.

Trompeter, G., Carpenter, T., Desai, N., Jones, K., & Riley, R, Jr. (2013). A synthesis of fraud-related research. Auditing: A Journal of Practice Theory, 32(Supplement), 287–321.

Trotman, K., Simnett, R., & Khalfia, A. (2009). Impact of the type of audit team discussions on auditors’ generation of material frauds. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(4), 1115–1142.

Wells, J. (2014). Principles of fraud examination. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wohl, M., Pritchard, E., & Kelly, B. (2002). How responsible are people for their employment situation? An application of the triangle model of responsibility. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 34(3), 201–209.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the generous help we received from The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) Research Foundation and from professionals at the participating public accounting firms, IIA chapters, and IIA affiliates. We also appreciate research assistance and helpful comments from Bruce Barrett, Steve Farmer, Francesca Gino, Dana Hermanson, Travis Holt, Denise Leggett, Mark Nelson, Kurt Reding, Barry Schlenker, Jonathan Stanley, Jeffrey Swerdlow, Mark Taylor, Erin Weber, and workshop and seminar participants at the American Accounting Association Auditing Midyear Conference, Kennesaw State University, and The University of Alabama.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The internal auditor results are summarized in a report provided to The IIA Research Foundation.

Appendix A: Experimental Materials

Appendix A: Experimental Materials

Panel A: Background Information

(Internal auditors only) HQT is a tool manufacturer that sells to distributors and select retailers. HQT is a publicly-held firm that has to file annual reports with governmental regulators. The company has had stable financial health and growth. Prior year results and current year planning indicate that HQT has effective internal controls and competent management and directors. The internal audit department, of which you are a member, has a very good reputation.

(External auditors only) HQT is a tool manufacturer that sells to distributors and select retailers. HQT is an SEC client and has been your firm’s audit client for 2 years. The company has had stable financial health and growth. Prior year results and current year planning indicate that HQT is an average risk client with effective internal controls and competent management, directors, and (in-house) internal auditors. Your firm has given unqualified audit opinions for each of the past 2 years. Your firm does not provide any non-audit services to HQT.

Summary (Unaudited) Annual Financial Information

Revenues | $13 million |

Pretax Income | $1.4 million |

Net Income | $1.0 million |

EPS | $1.05/share (forecast $1.04/share) |

A/R (net) | $1.0 million |

Inventory | $2.8 million |

Current Assets | $4.7 million |

PP&E (net) | $3.9 million |

Total assets | $10.5 million |

Current liabilities | $2.0 million |

Total liabilities | $5.6 million |

Total equity | $4.9 million |

Panel B: Fraud Treatments

(Financial statement fraud) During the fiscal year that you are about to audit, a new fraud has developed at HQT in an area where you will conduct audit work. Specifically, a member of HQT management prematurely recorded expenses by purchasing $100,000 of unneeded supplies prior to year-end and immediately expensed them as “Supplies Expense” even though none of the supplies were used. The manager was substantially under budget for the year and bought the supplies to use up the current year’s budget and prematurely start recognizing next year’s expenses.

(Misappropriation of assets) During the fiscal year that you are about to audit, a new fraud has developed at HQT in an area where you will conduct audit work. Specifically, a member of HQT management has stolen $100,000 cash from the company prior to year-end using a billing scheme. The manager created a fictitious (shell) company, sent false invoices to HQT for services that were not provided, and then converted the cash paid to the shell company.

(Corruption) During the fiscal year that you are about to audit, a new fraud has developed at HQT in an area where you will conduct audit work. Specifically, a member of HQT management has paid $100,000 in bribes this year to major distributors to ensure preferential treatment for HQT products. The fraudulent disbursements were expensed using an account called “Consulting Fees.”

Panel C: Triangle Model of Responsibility Link Questions (adapted from Schlenker et al. 1994)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeZoort, F.T., Harrison, P.D. Understanding Auditors’ Sense of Responsibility for Detecting Fraud Within Organizations. J Bus Ethics 149, 857–874 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3064-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3064-3