Abstract

Background

XRCC2 participates in homologous recombination and in DNA repair. XRCC2 has been reported to be a breast cancer susceptibility gene and is now included in several breast cancer susceptibility gene panels.

Methods

We sequenced XRCC2 in 617 Polish women with familial breast cancer and found a founder mutation. We then genotyped 12,617 women with breast cancer and 4599 controls for the XRCC2 founder mutation.

Results

We identified a recurrent truncating mutation of XRCC2 (c.96delT, p.Phe32fs) in 3 of 617 patients with familial breast cancer who were sequenced. The c.96delT mutation was then detected in 29 of 12,617 unselected breast cancer cases (0.23%) compared to 11 of 4599 cancer-free women (0.24%) (OR = 0.96; 95% CI 0.48–1.93). The mutation frequency in 1988 women with familial breast cancer was 0.2% (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.27–2.65). Breast cancers in XRCC2 mutation carriers and non-carriers were similar with respect to age of diagnosis and clinical characteristics. Loss of the wild-type XRCC2 allele was observed only in one of the eight breast cancers from patients who carried the XRCC2 mutation. No cancer type was more common in first- or second-degree relatives of XRCC2 mutation carriers than in relatives of the non-carriers.

Conclusion

XRCC2 c.96delT is a protein-truncating founder variant in Poland. There is no evidence that this mutation predisposes to breast cancer (and other cancers). It is premature to consider XRCC2 as a breast cancer-predisposing gene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the discovery of BRCA1 and BRCA2, more than 20 additional genes have been associated with a susceptibility to breast or ovarian cancer [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The XRCC2 gene is a member of the RAD51 gene family, which encodes proteins involved in homologous recombination repair of damaged DNA [9]. The XRCC2 gene acts in the Fanconi anemia—BRCA pathway of DNA repair [10,11,12]. In 2012, Park et al. identified six pathogenic coding variants in 1308 women with early-onset breast cancer from Europe, North America, and Australia and no variant in 1120 controls [13]. They also described ten breast-cancer families with protein-truncating or probably deleterious rare missense variants in XRCC2 among 689 multiple-case families [11]. Based on this, the XRCC2 gene has been included in several clinical cancer genetic test panels [3, 14, 15].

To verify whether a XRCC2 mutation confers elevated breast cancer risk and should be included in breast cancer test panels, we studied a large series of approximately 13,000 women with breast cancer and 5000 controls from Poland. In addition, we analyzed clinical characteristics of breast cancers in carriers of a XRCC2 mutation, and performed loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis at the XRCC2 locus in tumors from XRCC2 mutation-positive women.

Materials and methods

Hereditary breast cancer cases (case series 1)

We selected 617 unrelated probands from 617 Polish families with familial breast cancer and did exome sequencing on their germline DNA [16]. We included women with a strong family history for breast cancer. Among the 617 probands with breast cancer, there were 160 women from families with at least four women affected with breast cancer, 378 women from families with three affected, and 79 women from families with two affected (at least one had bilateral breast cancer or breast cancer below age 50). The mean number of breast cancers per family was 3.4. The mean age of breast cancer diagnosis among the 617 women was 46 years (range 28–76 years). These patients were selected from a registry of 3519 familial breast cancer cases housed at the Hereditary Cancer Center in Szczecin based on the number and age of onset of breast cancer cases among their relatives, and based on that they tested negative for a panel of 17 founder Polish mutations of BRCA1/2, CHEK2, PALB2, NBN, and RECQL [16,17,18,19,20].

Unselected cases of breast cancer (case series 2)

Unselected cases consisted of 12,679 prospectively ascertained cases of invasive breast cancer, diagnosed from 1996 to 2012, at 18 different hospitals in Poland (mean age 54, range 18–93) [19]. Patients were unselected for age, family history, and treatment. The patient participation rate was 76.1%. Information was recorded on clinical characteristics of breast cancers through review of medical records. Family history included the number of first- and second-degree relatives with cancer. 1988 patients reported at one first- or second-degree relative with breast cancer. Survival data were obtained (status: alive or dead, the date of death) from Polish Ministry of the Interior and Administration in July 2014. The Ethics Committee of Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin approved the study.

Controls

The control group included 4730 cancer-free Polish women aged 18 to 94 years (mean age, 53.0 years) from Poland [20].

Sequencing of the XRCC2 gene

We analyzed the entire coding sequence of XRCC2 from the exome sequencing data of 617 women with hereditary breast cancer (cases series 1) using the methodology described previously [16]. In brief, the Agilent SureSelect human exome kit (V6) was used for capturing target regions. The regions were sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500. The mean depth of coverage was approximately × 100; 97.4% of the CCDS exons were covered at × 20 depth of coverage and higher which used for variant calling.

Genotyping for XRCC2 c.96delT truncating mutation

We assessed DNA samples for a recurrent truncating mutation of XRCC2 (c.96delT) in a LightCycler Real-Time PCR 480 System (Roche Life Science, Mannheim, Germany) using a TaqMan assay (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA)—12,617 of 12,679 breast cancer cases, and 4599 of 4730 controls were successfully genotyped. All mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Sanger sequencing was performed using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and ABI prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Loss of heterozygosity analysis

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis at the XRCC2 locus was performed in micro-dissected tumors from eight women with XRCC2 c.96delT mutation using methodology described previously [21] with a minor modifications: (1) DNA was isolated with QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (QIAGEN); (2) LOH was analyzed by direct Sanger sequencing of the 104 bp DNA fragment containing the XRCC2 mutation (forward primer 5′ tctctcttcttttataagctccttg; reverse primer 5′ ttaccatgcacaggtgaatct).

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of the deleterious XRCC2 allele was estimated in 12,617 breast cancer cases and 4599 cancer-free women. Odds ratios were generated from two-by-two tables. Women with breast cancer, with and without the XRCC2 mutation, were compared for age at diagnosis, clinical features of the breast cancers, and survival. Statistical significance was assessed using Fisher exact test or Chi-squared test where appropriate. Means were compared using t test. To estimate the survival, we followed up women from the date of diagnosis until the date of death or July, 2014, if still alive. We compared the survival between mutation carriers and non-carriers by log-rank test.

Results

We identified a single XRCC2 protein-truncating mutation (c.96delT, p.Phe32fs) in 3 of 617 women with hereditary breast cancer. We did not see any other truncating XRCC2 mutation in the 617 subjects. The c.96delT mutation was present in 29 (0.23%) of 12,617 patients and in 11 (0.24%) of 4599 controls. The OR for risk of breast cancer in women with this XRCC2 mutation was 0.96 (95% CI 0.48–1.93). The mutation frequency in 1988 women with familial breast cancer was 0.2% (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.27–2.65, p = 0.99). The OR for breast cancer risk given the XRCC2 mutation was 1.01 for women diagnosed under 51 years of age, and was 0.92 for those diagnosed above age of 50 (Table 1).

The characteristics of breast cancers in patients with and without a XRCC2 mutation are shown in Table 2. Carriers and non-carriers were similar with respect to age at diagnosis, histology, tumor size, lymph node involvement, ER, and PR status. The frequency of bilateral tumors was the same in both groups (4.2% vs. 4.6%; p = 0.9).

Data on survival were available for 12,474 women with breast cancer. After the mean follow-up time of 64 months, there were 6 deaths (20.7%) recorded in 29 XRCC2 mutation carriers compared with 2101 deaths (16.8%) in 12,445 non-carriers (HR = 1.36; 95% CI 0.54–3.47; p = 0.45, log-rank test). The 10-year survival was 76% for the carriers compared to 75% for non-carriers.

Loss of the wild-type XRCC2 allele was observed in one of the eight breast cancers from women who carried XRCC2 c.96delT truncating mutation (Fig. 1).

To see if there might be an excess of cancer at other sites than the breast in a first- or second-degree relatives of carriers of a XRCC2 mutation, we reviewed the pedigrees of women who have breast cancer and carry the c.96delT mutation and compared these with the pedigrees of breast cancer cases without the c.96delT mutation. No cancer type was more common in first- or second-degree relatives of XRCC2 mutation carriers than in relatives of the non-carriers—there were in total 20 cancers in 26 families with the XRCC2 mutation (77%) versus 8380 cancers in 11,672 XRCC2 mutation-negative families (72%) (Table 3).

Discussion

In 2012, Park et al. suggested that XRCC2 is associated with elevated breast cancer risk based on finding six pathogenic coding variants in 1308 women with early-onset breast cancer from Europe, North America, and Australia and no variant in 1120 controls (p < 0.02) [13]. We were unable to verify this association in a much larger study from a homogeneous population.

Importantly we identified a recurrent truncating mutation of the XRCC2 gene (c.96delT, p.Phe32fs). This mutation is localized in the 5′ end of the gene at codon 32 and it is predicted to disrupt about 90% of XRCC2 protein sequence (that includes 280 aa) including the entire Rad51 domain, and therefore it is predicted to be deleterious. However, this specific mutation appears not to be associated with an elevated risk of familial breast cancer (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.27–2.65) or non-familial breast cancer (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.49–1.96). Further, breast cancers in XRCC2-mutation carriers and non-carriers were similar with respect to age of onset, clinical characteristics, and survival. Loss of the wild-type XRCC2 allele was observed only in one of the eight breast cancers from the Polish women who carried the c.96delT deletion.

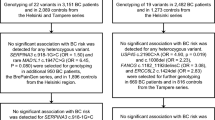

Our results are similar to those of Decker et al. [22] who reported no association of XRCC2 truncating mutations with breast cancer risk. They identified truncating XRCC2 mutations (11 different variants, five of these predicted to affect RAD51 domain) with the same frequency (0.07%) in 9 of 13,087 breast cancer cases and in 4 of 5488 controls from the UK (OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.26–4.19), but a twofold-increased risk could not be excluded. Hilbers et al. [23] analyzed XRCC2 for mutations in 3548 non-BRCA1/2 familial breast cancer cases and 1435 controls from the Netherlands, but found a protein-truncating variant in only one control. When we combine the three studies (from Poland, UK, and the Netherlands), truncating mutations of XRCC2 were detected in 38 of 29,252 (0.13%) breast cancer cases versus 16 of 11,522 (0.14%) controls and were not associated with breast cancer risk (meta-analysis OR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.50–1.57, Mantel–Haenszel method).

It is also important to establish if missense mutations of XRCC2 confer increased breast cancer risk. In 2016, Hilbers et al. [24] functionally characterized 27 variants in XRCC2 by testing their ability to restore XRCC2-DNA repair-deficient phenotypes. Only the protein-truncating mutations (4 variants), but not missense variants (23 variants) were unable to restore XRCC2 deficiency. Rare non-protein-truncating variants were detected with the same frequency (0.6%) in 3548 non-BRCA1/2 familial breast cancer cases and 1,435 controls from the Netherlands [23]. We did not detect any missense variants of XRCC2 which are predicted to be pathogenic using in silico tools in 617 Polish families with hereditary breast cancer who were fully sequenced. These data suggest that missense variants of XRCC2 are unlikely to be pathogenic for breast cancer.

Our study is large and population based. Poland is homogeneous from a genetic perspective and the range of mutant alleles is limited, that is reflected by the presence of a large number of founder mutations [16]. Our analysis suggests that mutations of XRCC2 do not confer elevated breast cancer risk. Normally, a genetic counselor or physician who is given a result that a truncating mutation is present (i.e., a mutation that leads to loss of protein function) will assume that it is deleterious. In the case of the c.96delT (p.Phe32fs) mutation, our epidemiology analysis excludes this variant as pathogenic for breast cancer. It is possible that other variants (truncating or non-truncating) are pathogenic, but this will be exceedingly difficult for a counselor to prove on a single-case basis. The consequences of assigning a high-risk status to a woman based on an XRCC2 mutation are non-trivial and may lead to increased psychological distress and possibly to unwarranted preventive surgery. In our opinion, XRCC2 should not be included on the genetic testing panels.

References

Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, Cochran C, Bennett LM, Ding W (1994) A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 266:66–71. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7545954

Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, Collins N, Gregory S, Gumbs C, Micklem G (1995) Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature 378:789–792. https://doi.org/10.1038/378789a0

Easton DF, Pharoah PD, Antoniou AC, Tischkowitz M, Tavtigian SV, Nathanson KL, Devilee P, Meindl A, Couch FJ, Southey M et al (2015) Gene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer risk. N Engl J Med 372:2243–2257. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1501341

Kurian AW, Hare EE, Mills MA, Kingham KE, McPherson L, Whittemore AS, McGuire V, Ladabaum U, Kobayashi Y, Lincoln SE et al (2014) Clinical evaluation of a multiple-gene sequencing panel for hereditary cancer risk assessment. J Clin Oncol 32:2001–2009. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6607

LaDuca H, Stuenkel AJ, Dolinsky JS, Keiles S, Tandy S, Pesaran T, Chen E, Gau CL, Palmaer E, Shoaepour K et al (2014) Utilization of multigene panels in hereditary cancer predisposition testing: analysis of more than 2,000 patients. Genet Med 16:830–837. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.40

Lu HM, Li S, Black MH, Lee S, Hoiness R, Wu S, Mu W, Huether R, Chen J, Sridhar S et al (2018) Association of breast and ovarian cancers with predisposition genes identified by large-scale sequencing. JAMA Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2956

Hauke J, Horvath J, Groß E, Gehrig A, Honisch E, Hackmann K, Schmidt G, Arnold N, Faust U, Sutter C et al (2018) Gene panel testing of 5589 BRCA1/2-negative index patients with breast cancer in a routine diagnostic setting: results of the German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Med 7:1349–1358. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1376

Girard E, Eon-Marchais S, Olaso R, Renault AL, Damiola F, Dondon MG, Barjhoux L, Goidin D, Meyer V, Le Gal D et al (2019) Familial breast cancer and DNA repair genes: insights into known and novel susceptibility genes from the GENESIS study, and implications for multigene panel testing. Int J Cancer 144:1962–1974. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31921

Tambini CE, George AM, Rommens JM, Tsui LC, Scherer SW, Thacker J (1997) The XRCC2 DNA repair gene: identification of a positional candidate. Genomics 41:84–92. https://doi.org/10.1006/geno.1997.4636

Park JY, Virts EL, Jankowska A, Wiek C, Othman M, Chakraborty SC, Vance GH, Alkuraya FS, Hanenberg H, Andreassen PR (2016) Complementation of hypersensitivity to DNA interstrand crosslinking agents demonstrates that XRCC2 is a Fanconi anaemia gene. J Med Genet 53:672–680. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103847

Meindl A, Hellebrand H, Wiek C, Erven V, Wappenschmidt B, Niederacher D, Freund M, Lichtner P, Hartmann L, Schaal H et al (2010) Germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees establish RAD51C as a human cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet 42:410–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.569

Berwick M, Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Carlson A, Mah K, Henry R, Diotti R, Milton K, Pujara K, Landers T et al (2007) Genetic heterogeneity among Fanconi anemia heterozygotes and risk of cancer. Cancer Res 67:9591–9596. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1501

Park DJ, Lesueur F, Nguyen-Dumont T, Pertesi M, Odefrey F, Hammet F, Neuhausen SL, John EM, Andrulis IL, Terry MB et al (2012) Rare mutations in XRCC2 increase the risk of breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet 90(4):734–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.027

Bonache S, Esteban I, Moles-Fernández A, Tenés A, Duran-Lozano L, Montalban G, Bach V, Carrasco E, Gadea N, López-Fernández A et al (2018) Multigene panel testing beyond BRCA1/2 in breast/ovarian cancer Spanish families and clinical actionability of findings. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 144:2495–2513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2763-9

Maksimenko J, Irmejs A, Trofimovičs G, Bērziņa D, Skuja E, Purkalne G, Miklaševičs E, Gardovskis J (2018) High frequency of pathogenic non-founder germline mutations in. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 16:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-018-0094-0

Cybulski C, Kluźniak W, Huzarski T, Wokołorczyk D, Kashyap A, Rusak B, Stempa K, Gronwald J, Szymiczek A, Bagherzadeh M et al (2019) The spectrum of mutations predisposing to familial breast cancer in Poland. Int J Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32492

Szwiec M, Jakubowska A, Górski B, Huzarski T, Tomiczek-Szwiec J, Gronwald J, Dębniak T, Byrski T, Kluźniak W, Wokołorczyk D et al (2015) Recurrent mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Poland: an update. Clin Genet 87:288–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12360

Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Jakubowska A, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Masojć B, Deebniak T, Górski B, Blecharz P et al (2011) Risk of breast cancer in women with a CHEK2 mutation with and without a family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:3747–3752. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0778

Cybulski C, Kluźniak W, Huzarski T, Wokołorczyk D, Kashyap A, Jakubowska A, Szwiec M, Byrski T, Dębniak T, Górski B et al (2015) Clinical outcomes in women with breast cancer and a PALB2 mutation: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol 16:38–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70142-7

Cybulski C, Carrot-Zhang J, Kluźniak W, Rivera B, Kashyap A, Wokołorczyk D, Giroux S, Nadaf J, Hamel N, Zhang S et al (2015) Germline RECQL mutations are associated with breast cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet 47:643–646. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3284

Cybulski C, Górski B, Debniak T, Gliniewicz B, Mierzejewski M, Masojć B, Jakubowska A, Matyjasik J, Złowocka E, Sikorski A et al (2004) NBS1 is a prostate cancer susceptibility gene. Cancer Res 64:1215–1219. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2502

Decker B, Allen J, Luccarini C, Pooley KA, Shah M, Bolla MK, Wang Q, Ahmed S, Baynes C, Conroy DM et al (2017) Rare, protein-truncating variants in ATM, CHEK2 and PALB2, but not XRCC2, are associated with increased breast cancer risks. J Med Genet 54:732–741. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104588

Hilbers FS, Wijnen JT, Hoogerbrugge N, Oosterwijk JC, Collee MJ, Peterlongo P, Radice P, Manoukian S, Feroce I, Capra F et al (2012) Rare variants in XRCC2 as breast cancer susceptibility alleles. J Med Genet 49:618–620. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101191

Hilbers FS, Luijsterburg MS, Wiegant WW, Meijers CM, Völker-Albert M, Boonen RA, van Asperen CJ, Devilee P, van Attikum H (2016) Functional analysis of missense variants in the putative breast cancer susceptibility gene XRCC2. Hum Mutat 37:914–925. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23019

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Science Centre, Poland; Project Number: 2015/17/B/NZ5/02543. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin. Patient clinical data have been obtained in a manner conforming with the IRB ethical guidelines. We thank Daria Zanoza and Ewa Putresza for their help with managing databases.

The members of Polish Hereditary Breast Cancer Consortium are as follows: M. Bębenek, D. Godlewski, S. Gozdecka-Grodecka, S. Goźdź, O. Haus, H. Janiszewska, M. Jasiówka, E. Kilar, R. Kordek, B. Kozak-Klonowska, G. Książkiewicz, A. Mackiewicz, E. Marczak, J. Mituś, Z. Morawiec, S. Niepsuj, R. Sibilski, M. Siołek, J. Sir, D. Surdyka, A. Synowiec, C. Szczylik, R. Uciński, B. Waśko, R. Wiśniowski, T. Byrski, and B. Górski.

Funding

This study was funded by National Science Centre (Narodowe Centrum Nauki), Poland, Project Number: 2015/17/B/NZ5/02543.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The members of the Polish Hereditary Breast Cancer Consortium are listed in Acknowledgement section.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kluźniak, W., Wokołorczyk, D., Rusak, B. et al. Inherited variants in XRCC2 and the risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 178, 657–663 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05415-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05415-5