Abstract

Purpose

The molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) is critical to identify the key drivers of cancer metastasis and devising therapeutic approaches, particularly for inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) which is usually diagnosed at advance stages and progresses rapidly.

Methods

Genomic alterations in tumor tissue samples were studied using Foundation One™. Single CTCs were isolated using CellSearch followed by single-cell isolation by DEPArray™. Samples with 20 or more CTCs were chosen to isolate single CTCs using the DEPArray™.

Results

Genomic alterations were studied in primary tumor or metastatic sites from 32 IBC patients. Genes with high-frequency mutations were as follows: TP53 (69%), RB1 (16%), PIK3CA (13%), and also ErbB2 (3%). At least once during treatment, CTCs were detected in 26 patients with metastatic IBC, in two patients with locally advanced IBC, and four patients had no detectable CTCs. Per 7.5 mL of blood, fifteen patients (47%) had ≥20 CTCs and six of them were chosen at random to isolate single CTCs. These cells were tested for the presence of TP53, RB1, PIK3CA, and/or ErbB2 mutations previously found in matching tissue biopsies. The isolated CTCs showed the same mutations as primary or metastatic tumor samples. Intra-patient CTC heterogeneity was found by the presence of different CTC subclones, with some CTCs harboring different combinations of mutated and wild-type genes.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that CTCs could represent a non-invasive source of cancer cells from which to determine genetic markers as the disease progresses and identify potential therapeutic targets in IBC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a very aggressive type of advanced breast cancer with a poor prognosis. The clinical symptoms of IBC involve the rapid onset of changes in the skin overlaying the breast, including edema, redness, and swelling, exhibiting a wrinkled, orange peel-like appearance of the skin known as peau d’orange [1]. This peculiar presentation is associated with the invasion of aggregates of tumor cells, defined as tumor emboli, into the dermal lymphatics, where they obstruct the lymph channels [2, 3]. IBC currently accounts for only 2–6% of all breast cancer cases in the United States and up to 20% of all breast cancer cases globally [4–7]. Due to its propensity to rapidly metastasize, it is responsible for a disproportionate number (15%) of breast cancer-related deaths [7–9]. IBC is either stage III or IV; at the time of diagnosis, virtually all patients have lymph node metastases and one third of the patients have metastases in distant organs such as the brain, the bones, and/or the visceral organs [6].

Metastatic disease is the most common cause of cancer-related death in patients with solid tumors and it is often associated with the presence of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the peripheral blood of cancer patients [10]. CTCs have been detected in a majority of epithelial cancers, including prostate [11], colorectal [12], and breast cancers [13]. CTCs are tumor cells shed from either the primary tumor or its metastases and can thus be regarded as “liquid biopsies” of metastasizing cells. Although their exact composition is unknown, a fraction of these cells is thought to be viable metastatic precursors capable of initiating a clonal metastatic lesion [14, 15]. Little is known about the timing of CTC release from primary tumors, their functional properties, or their heterogeneity. Intra-tumor heterogeneity denotes the coexistence of subpopulations of cancer cells that differ in their genetic, phenotypic, or behavioral characteristics within a given primary tumor and between a given primary tumor and its metastasis. Thus, intra-tumor heterogeneity poses a tremendous challenge for the characterization of biomarkers and treatments selection. In this work, we isolated single CTCs from the blood of IBC patients in order to analyze the presence of different mutations found in the primary tumor or metastatic sites and determine the heterogeneity of these cells.

Materials and methods

Patients

Thirty-two patients with inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) undergoing systemic treatment for their disease were included in this study. At the time of the first CTC enumeration, 29 patients had metastatic IBC (Stage IV) and three patients had locally advance IBC (Stage III). Clinical details and treatment timelines for the 32 patients are given in Supplementary Information. Targeted treatment outcomes have also been reported elsewhere on patients D84455 [16] and I77438 [17].

Genomic studies in tumor samples

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor tissues (breast, chest wall, lymph node, bone marrow, liver biopsy, abdominal skin punch, brain biopsy, and/or pleural fluids) were used for genomic studies. Ten unstained sections were cut (5–10 µm) and placed on charged slides and submitted to Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA) for genetic analysis. Briefly, DNA was isolated from the fixed tumor cells and genomic analysis was performed using next-generation sequencing (NGS) (Foundation One™).

CTCs enumeration from the blood using CellSearch

One tube of 7.5 mL blood from the IBC patients was drawn and the CellSearch™ System was used for CTC enrichment and enumeration. After running the blood in the CellSearch™ system for CTC enumeration, the cells were recovered from the cassettes in order to be used for single CTC selection using the DEPArray™ System (Silicon Biosystems, San Diego, CA). The standard protocol used for CTC enrichment is described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. Samples containing a minimum of 20 CTCs were selected and prepared for single-cell selection using the DEPArray™.

Isolation of single CTCs using the DEPArray™ system

After the CellSearch enrichment, single CTCs were selected and isolated using the DEPArray™ (Silicon Biosystems) as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. Individual CTCs or clustered cells that were α-cytokeratin (PE)-positive, CD45 (APC)-negative, and DAPI-positive were recovered in several tubes for genomic analysis. In addition, individual white blood cells (WBC) classified as CD45 (APC)-positive, CK (PE)-negative, and DAPI-positive were selected and recovered as single cells to use as controls in the genomic studies. Selected cells were stored at −80 °C for genomic analyses.

TP53, ErbB2, PIK3CA, and RB1 mutations in CTCs

Whole genome amplification (WGA) was performed using the Ampli1™ WGA Kit (Silicon Biosystems). The Ampli1™ WGA kit uses a polymerase with proofreading activity with a lower error rate (4.8 × 10−6) than standard Taq DNA polymerases. Global amplification consisting of DNA isolation, restriction digestion, adaptor ligation, and PCR amplification was performed as described in Supplemental Materials and methods [18]. To study TP53, ErbB2, and PIK3CA mutations in CTCs, reverse and forward primers were used (Supplementary Table 1). The PCR products were cleaned using the QIAquick PCR purification kit and sequenced using the ABI 3130XL capillary genetic analyzer. As we were unsuccessful in studying RB1 K720* mutation using specific primers as described before for other genes, this mutation was studied using next-generation sequencing (NGS) as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Results

Mutation analysis of tissue samples from metastatic IBC patients

A total of 32 patients with IBC were included in the study (Tables 1 and 2). All the patients were females save one male (B87480, Table 1), and all of them were at an advanced clinical stage at time of diagnosis (stage III or IV). Their median age at diagnosis was 48 years with a range of 32–72 years old. From the 32 patients, 20 patients (62.5%) had triple-negative (ER-negative, PgR-negative, and Her2-negative) IBC (Table 1); five patients (15.6%) had ER-positive Her2-negative IBC; three patients (9.4%) had ER-negative Her2-positive IBC; and four patients (12.5%) had ER-positive Her2-positive IBC at time of diagnosis (Table 2).

The genomic alterations in the primary tumor or metastatic sites were determined using the NGS-based cancer gene test, Foundation One™ (Tables 1 and 2). IBC patients showed mutations in the following: TP53 (22/32; 69%), RB1 (5/32; 16%), PIK3CA (4/32; 13%), BRCA1 (3/32; 9%), BRCA2 (3/32; 9%), and Notch1 (3/32; 9%). Other mutated genes were ErbB2 (or Her2; 3%), ATM, Kras, ESR1, EGFR, and PAX5. Also IBC tumor samples showed amplifications in the following: MYC (8/32; 25%), CCND1 (7/32; 22%), ErbB2 (5/32; 16%), MCL1 (6/32; 19%), and FGFR1 (3/32; 9%). Interestingly, patient D66122, who was found to have a triple-negative disease by the analysis of her first biopsy, a second chest wall biopsy in month 26 showed amplification of the ErbB2 gene. Based on these results, this patient was subsequently treated with Herceptin (Table 1 and Supplementary Information).

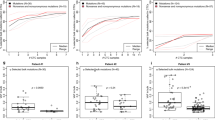

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) enumeration

The number of CTCs present in 7.5 mL of blood was determined at different points during the patients’ treatments using the CellSearch™ system. From the 32 IBC patients, CTCs were detected in 28 patients (≥5 CTCs/7.5 mL blood in 24 patients; <5 CTCs/7.5 mL blood in four patients) at least once during treatment, while four patients had no detectable CTCs at any point during treatment (Tables 1 and 2). CTCs were detected in 26 patients with metastatic IBC and two patients with locally advance IBC. From 20 patients with triple-negative IBC, 16 patients had ≥5 CTCs/7.5 mL blood, and four patients had 0–4 CTCs/7.5 mL blood. Patients with triple-negative IBC had significantly worse overall survival compared to those with ER-positive Her2-positive IBC (p = 0.011), ER-positive Her2-negative IBC (p = 0.001), and ER-negative Her2-positive IBC (p = 0.027) (Fig. 1). Patients in the ER-positive Her2-negative group had the longest median survival (ER-positive Her2-negative = 76 months (95% CI 39–101), Triple-Negative = 31.5 months (95% CI 20–38), ER-negative Her2-positive = 39 months (95% CI 23–59.), ER-positive Her2-positive = 49.5 months (95% CI 21-undet.) (Figure 1). In the ER-positive Her2-positive group at the time of diagnosis (Table 2), patient K76386 developed a ER-positive (weak) Her2-negative component in month 9; and a tumor biopsy performed from patient B62630 in month 49 showed that the tumor was ER-positive Her2-negative (Supplementary Information). CTCs were detected in 26 patients with metastatic IBC (Stage IV) and in two patients with locally advance IBC (Stage III) at least once during treatments (Tables 1 and 2). CTCs were not detected in patient B87480 with triple-negative IBC (Table 1) nor in patients S71769, I77438, and J70105 with Her2-positive IBC (Table 2).

Survival curves according to ER (estrogen receptor) and Her2 (ErbB2) status. Overall survival in the triple-negative group was lower than the other groups (TN vs ER− Her2+, p = 0.011; TN vs ER+ Her2+, p = 0.001; TN vs ER+ Her2−, p = 0.027). Patients from the ER+ Her2− group had the longest median survival (76 months, 95% CI 39–101). In the ER+ Her2+ group, one patient was still alive and shown as censored (+) at the end of the curve

In order to successfully isolate single CTC using the DEPArray, samples from the CellSearch that contain at least 20 CTCs were used. Per 7.5 mL of blood from the 32 IBC patients, fifteen (47%) patients had ≥20 CTCs, two (6%) patients had 10–20 CTCs, five patients (16%) had between 5 and 10 CTC, and six patients (19%) had 1–5 CTCs. Of the 20 patients with triple-negative IBC, CTCs were detected in 19 of them at some point during the course of their disease, and 11 of these patients (55%) had more than 20 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood (Table 1). CTCs were detected in all five patients with ER-positive Her2-negative IBC at least once during their treatment and two of these patients had more than 20 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood (Table 2). Of the seven patients with Her2- positive IBC, three patients did not show any CTCs (although CTCs were enumerated only once in them), and two patients had more than 20 CTCs (Table 2). The two ER-positive Her2-positive IBC patients with a high number of CTCs were initially responsive to Herceptin therapy but during disease progression they failed to respond to the treatment (K76386 and B62630; Table 2).

Mutations in single circulating tumor cell (CTC)

From the fifteen patients that had ≥20 CTCs, six were chosen at random in order to isolate single CTCs using the DEPArray™ (Table 3). Among these patients, all but patient B62630 had triple-negative IBC at diagnosis but, developed a Her2-negative component during disease progression as it was previously mentioned (Supplementary Information). For molecular characterization of single CTCs, cells were recovered from the CellSearch cassettes after enumeration as it was described in Supplementary Materials and Methods, washed and loaded in the DEPArray cassettes for single-cell isolation. The DEPArray™ system (Silicon Biosystems, San Diego, CA) is an automated platform that uses dielectrophoresis and a high-quality image-based cell selection system that allows for the identification and recovery of individual cells from heterogeneous samples [18]. CTCs that were discrete single cells were seen in the blood of three patients (J73299, R85453 and T77549), whereas the remaining three patients (B62630, L67504, and D84455) had both individual single CTCs and clusters of associated CTCs (Table 3). Usually, CTCs clusters were composed by five to 14 associated cells (Fig. 2). Samples containing single CTCs, pooled single CTCs, and/or CTCs clusters were selected and recovered using DEPArray™, and the samples were tested for the presence of mutations previously revealed in tumor samples from the same patient. WGA was performed on the isolated CTCs and regions of TP53, ErbB2, and PIK3CA shown to be mutated in matching tumor tissue were amplified and sequenced using Sanger’s method. In five of the six IBC patients where TP53 was mutated in the tumor tissues, the isolated CTCs showed the same TP53 mutations (Table 3). However, a TP53 S215G mutation was present in a chest wall biopsy in patient B62630, which was not observed in either the isolated CTCs or in tumor cells collected from pleural effusion (Table 2, pleural effusion from month 50). The TP53 S215G mutation is a missense mutation in exon 6 (Table 3). The other patients, J73299, R85453, L67504, and D84455, had TP53 mutations that produced a premature stop codon in the protein (Table 3). The liver biopsy of patient J73299 showed a mutation in TP53 exon 6, TP53 P190_H193 > *E; this mutation was also found in CTCs isolated from the patient’s blood (Table 3). Two patients (R85453 and L67504) had a TP53 mutation in exon 4, TP53 R110 fs*13 (Table 3). In patient L67504, a C deletion (nucleotide 328, delC) was detected in the chest wall biopsy and the same mutation was found in the CTCs (Table 3). Patient R85453 showed a G deletion (nucleotide 329, delG) in p53 exon 4 in a breast biopsy sample (Table 1); while this mutation was also found in one CTC isolated from the patient, a second CTC revealed a C deletion (nucleotide 328, delC) that was not previously detected in the tissue biopsy (Table 3). The chest wall biopsy of patient D84455 showed a TP53 C229 fs*10 mutation that was also found in three of five single CTCs analyzed and in one CTC cluster isolated from the patient’s blood; one single CTC showed the TP53 wild-type allele and one CTC provided no data as we were unable to successfully amplify the region of interest (Table 3). In Table 4, the deleterious mutations in TP53 are shown.

Single and clusters of CTCs from a patient with triple-negative metastatic IBC visualized in the DEPArray™. Tumor cells were defined as presence of a clear DAPI-stained nucleus, CK-PE-positive cytoplasm, and CD-45-APC negativity. Separate images for PE (green), DAPI (magenta), APC (blue) fluorescence, bright field channels, and merged CK-PE/DAPI and CD45-APC/DAPI images are shown. Single CTCs and a cluster of CTCs from a metastatic triple-negative IBC patient (D84455) are shown; also, four white blood cells (WBC) collected to use as controls for the molecular studies are shown

The RB1 gene was mutated at high frequency in IBC patients; CTCs isolated from patients T77549 and L67504 were chosen to further study RB1 mutations in single CTCs (Table 3). RB1 splice mutation 607 + 1 G > C was detected in the chest wall biopsy from T77549 and this mutation was detected in one single CTC and in one pool of 6 CTCs isolated from the blood of that patient (Table 3). A second pooled cell sample containing 4 CTCs harbored RB1 wild type. The RB1 607 + 1 G > C denotes the G to C substitution at nucleotide +1 of the intron (between exons 6 and 7) in the coding DNA positioned between nucleotide 607 and 608, resulting in low expression or partial inactivation of the RB1 protein. Patient L67504 showed a RB1 K720* mutation in her chest wall (Table 1); the RB1 K720* mutation was also found in two of five single CTCs and a cluster containing three CTCs that were isolated from the blood (Table 3). The RB1 K720* mutation is a nonsense variant, a substitution that produces an immediate stop codon. This patient also showed a BRCA2 p.A1326 fs*4 mutation in her chest wall biopsy (Table 1); the BRCA2 p.A1326 fs*4 mutation was detected in one of three white blood cells (WBC) used as controls, suggesting that the BRCA2 mutation is a germline mutation. This mutation was not investigated in the isolated CTCs. In both patients that had RB1 mutations, some CTCs showed the RB1 mutations and others showed the wild-type RB1 allele (Table 3).

The chest wall biopsy from patient D84455 had two mutations in ErbB2: S310F in exon 12, and V777L in exon 24; this patient also had a mutation in PIK3CA K111E, in addition to the TP53 C229 fs*10 mutation previously described (Table 3). These mutations were studied in five single CTCs and one CTC cluster. Two single CTCs and the cluster showed all the mutations detected in the chest wall biopsy; another single CTC only showed the ErbB2 mutations (ErbB2 S310F and ErbB2 V777L) and wild-type alleles of TP53 and PIK3CA. Another single CTC showed the ErbB2 mutation on exon 12 (ErbB2 S310F), the wild-type allele on exon 24, but the amplified DNA was not enough to study TP53 and PIK3CA in this cell (Table 3). The remaining single CTC showed the mutated TP53 (TP53 C229 fs*10) and ErbB2 exon 24 wild type. Results indicated that patients D84455 and L67504, in which mutations in more than one gene were studied, had a heterogeneous population of CTCs (Table 3).

Discussion

Genomic alterations were studied in primary and/or metastatic tumor samples from 32 patients with IBC. Most of the patients had triple-negative IBC and had mutations in TP53, RB1, and/or PIK3CA. CTCs were detected in 28 of the 32 IBC patients included in this study. Single CTCs isolated from the blood of six of these patients showed the same mutations as primary or metastatic tumor samples indicating that CTCs can potentially be used to monitor disease progression. Our results show that mutations in driver genes found in the primary tumor and/or the metastasis in IBC patients could be identified in the CTCs. Furthermore, the mutational analysis of the TP53, RB1, PIK3CA, and ErbB2 genes revealed heterogeneity of CTCs.

Deleterious TP53 mutations found in tissue samples or pleural effusions of IBC patients were also present in CTCs isolated from their blood. In the majority of the IBC patients with TP53 mutations, these mutations resulted in a non-functional protein. A non-functional TP53 has been shown to offer survival advantages to the cancer cells by facilitating growth, anoikis resistance, and the emergence of a potentially more aggressive malignancy [19]. TP53 mutations are exceptionally frequent in cancer and are among the key driving factors in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [20]. Furthermore, TP53 mutations are more frequent in inflammatory breast cancer (50%) than in non-inflammatory breast cancer (20–30%) [21, 22]. TP53 mutations have been shown to predict a poor response to anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy [23–25]; others suggested that TP53 mutations confer sensitivity to taxane [26, 27]. A recent study suggested that patients with TP53 mutations are more likely to respond to anthracycline/cyclophosphamide-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy [28]. Several clinical trials are ongoing to study TP53-mutated breast cancer sensitivity to different chemotherapeutic agents. Other clinical trials are targeted towards either expression of the wild-type TP53, suppressing expression of mutated TP53, or strategies that involve targeting of the cell cycle regulator Wee-1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (clinicaltrials.gov).

RB1 mutations were found in only the triple-negative IBC patients from this study, and all of these mutations render a premature stop codon and a non-functional RB1 protein. RB1 mutations were also detected in the CTCs. RB1 mediates cell cycle control and is frequently inactivated in human TNBC [29–31]. There are targeted inhibitors that are currently in advanced clinical testing for tumors harboring RB1 and PIK3CA mutations [32, 33].

One triple-negative IBC patient (D84455) with a deleterious TP53 mutation also showed two ErbB2 mutations (V777L and S310F). Both mutations activate ErbB2 by either affecting its auto-phosphorylation or phosphorylation of downstream substrates in breast cancer cells [34–36]. Initially, this patient had ER+ Her2+ invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) in the left breast that was treated with standard local therapies over 2 years and this patient subsequently developed triple-negative IBC in the same breast [16] (Supplementary Information). This suggests that the ErbB2 pathway could be the driver of this patient’s disease even in the absence of ErbB2 amplification. Furthermore, this patient had a PIK3CA K111E mutation which is also an activating mutation [37, 38]. All the mutations detected in the chest wall biopsy of patient D84455 were detected in the CTCs isolated from their blood. A heterogeneous population of CTCs were found in this patient with some CTCs showing the mutated genes and others showing different combinations of the mutated and wild-type genes.

It has been successfully demonstrated by single-cell sequencing that many breast cancers are composed of multiple distinct subclones [39]. Intra-patient cellular heterogeneity is widely reported in epithelial malignancies and it is expected that CTCs will also be heterogeneous [40–42]. Our results are consistent with previous findings which showed a heterogeneous pattern of genomic mutations on single CTCs obtained from breast, esophageal, and colorectal cancer patients [42–44].

Our results demonstrate that we were able to select uncontaminated CTCs by combining the CellSearch and DEPArray™ systems. However, one disadvantage of the DEPArray™ is that there is approximately 40% cell-loss, although the DEPArray cartridge is manually loaded with 14 μL of sample, only 9.26 μL of sample is injected into the micro-chamber of the cartridge. We found that in order to successfully isolate single CTC, samples with 20 CTCs or more should be used to load in the DEPArray cassette. In order to perform molecular analysis of CTCs in samples with less than 20 CTCs per 7.5 mL blood, multiple samples from the same patient could potentially be combined after the CellSearch and loaded in the DEPArray cassette.

However, despite the promise of CTCs as multifunctional biomarkers, there are still numerous challenges that hinder their incorporation into standard clinical practice. Some patients showed little to no CTCs even though their disease was progressing. This is the case for most of the patients with Her2-positive IBC, with the exception of patients K76386 and B62630 who developed a Her2-negative component during their disease progression; both had high number of CTCs. Patients with Her2-positive IBC were treated with Herceptin for a long period of time, so this could explain why CTCs were not present in their blood due to the high specificity of these antibodies. In addition, the CellSearch™, relies on the detection of the surface epithelial cell adhesion molecule EpCAM, and the existence of an EpCAM-negative subpopulation of CTCs had been described in patients with Her2-positive metastatic breast cancer [45]; therefore, it will be interesting to combine different pre-enrichment strategies with the DEPArray in order to study these cells, especially in Her2-positive IBC.

It has been shown that elevated CTC at baseline or at any time through the course of metastatic breast cancer is associated with worse prognosis; patients with ≥5 CTCs/7.5 mL blood had a shorter overall survival compared with the patients with <5CTCs/7.5 mL blood, and elevated CTCs while on treatment ultimately are predictive of an ineffective therapy [13, 46]. Our data showed that the distribution of CTCs in the patients with serial blood draws during the treatments varied; many patients were initially CTCs negative but converted to positive and vice versa. Based on our results, single time-point measurements of CTCs seem to be inadequate, and could result in incorrect microscopic disease staging. Collecting sequential blood samples for real-time monitoring of the efficacy of systemic therapies would offer new possibilities in evaluating targeted therapies based on genomic profiling of CTCs and improving the clinical management of patients with IBC. In order to implement these studies in future clinical practice, we are developing protocols in order to study mutations in single, pools, and clusters of CTCs using NGS and a panel of 15 genes frequently mutated in IBC.

This work demonstrates that the isolation and pooling of CTCs from IBC patients can be used for genomic analysis, both to initially identify targetable mutations where solid tumor samples are unavailable and to be used as a biomarker to reveal which cell populations are affected by the current or previous therapy. Our results suggest that CTCs represent the entire spectrum of the primary tumor and distal metastases for patients with IBC. Furthermore, our studies showed the presence of different CTCs subclones in the peripheral blood of IBC patients.

Abbreviations

- CK:

-

Cytokeratin

- CTC:

-

Circulating tumor cell

- EpCAM:

-

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- ErbB2 or Her2:

-

v-erb-b2 avian erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2

- FFPE:

-

Formalin- fixed paraffin embedded

- Fs:

-

Frameshift

- IBC:

-

Inflammatory breast cancer

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PE:

-

Phycoerythrin

- PgR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- RB1:

-

Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor

- TN:

-

Triple-negative

- TNBC:

-

Triple-negative breast cancer

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

- WGA:

-

Whole genome amplification

References

Cristofanilli M, Valero V, Buzdar AU, Kau SW, Broglio KR, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Sneige N, Islam R, Ueno NT, Buchholz TA, Singletary SE, Hortobagyi GN (2007) Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) and patterns of recurrence: understanding the biology of a unique disease. Cancer 110(7):1436–1444

Alpaugh ML, Tomlinson JS, Kasraeian S, Barsky SH (2002) Cooperative role of E-cadherin and sialyl-Lewis X/A-deficient MUC1 in the passive dissemination of tumor emboli in inflammatory breast carcinoma. Oncogene 21(22):3631–3643

Molckovsky A, Fitzgerald B, Freedman O, Heisey R, Clemons M (2009) Approach to inflammatory breast cancer. Can Fam Physician 55(1):25–31

Cristofanilli M, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN (2003) Update on the management of inflammatory breast cancer. Oncologist 8(2):141–148

Dawood S, Cristofanilli M (2011) Inflammatory breast cancer: what progress have we made? Oncology (Williston Park) 25(3):264–273

Robertson FM, Bondy M, Yang W, Yamauchi H, Wiggins S, Kamrudin S, Krishnamurthy S, Le-Petross H, Bidaut L, Player AN, Barsky SH, Woodward WA, Buchholz T, Lucci A, Ueno NT, Cristofanilli M (2010) Inflammatory breast cancer: the disease, the biology, the treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 60(6):351–375

Hance KW, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Young HA, Levine PH (2005) Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program at the National Cancer Institute. J Natl Cancer Inst 97(13):966–975

Anderson WF, Schairer C, Chen BE, Hance KW, Levine PH (2005) Epidemiology of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). Breast Dis 22:9–23

Levine PH, Veneroso C (2008) The epidemiology of inflammatory breast cancer. Semin Oncol 35(1):11–16

Alunni-Fabbroni M, Sandri MT (2010) Circulating tumour cells in clinical practice: methods of detection and possible characterization. Methods 50(4):289–297

Danila DC, Heller G, Gignac GA, Gonzalez-Espinoza R, Anand A, Tanaka E, Lilja H, Schwartz L, Larson S, Fleisher M, Scher HI (2007) Circulating tumor cell number and prognosis in progressive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13(23):7053–7058

Cohen SJ, Alpaugh RK, Gross S, O’Hara SM, Smirnov DA, Terstappen LW, Allard WJ, Bilbee M, Cheng JD, Hoffman JP, Lewis NL, Pellegrino A, Rogatko A, Sigurdson E, Wang H, Watson JC, Weiner LM, Meropol NJ (2006) Isolation and characterization of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 6(2):125–132

Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ, Terstappen LW, Hayes DF (2004) Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 351(8):781–791

Yu M, Ting DT, Stott SL, Wittner BS, Ozsolak F, Paul S, Ciciliano JC, Smas ME, Winokur D, Gilman AJ, Ulman MJ, Xega K, Contino G, Alagesan B, Brannigan BW, Milos PM, Ryan DP, Sequist LV, Bardeesy N, Ramaswamy S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA (2012) RNA sequencing of pancreatic circulating tumour cells implicates WNT signalling in metastasis. Nature 487(7408):510–513

Lee JS, Magbanua MJ, Park JW (2016) Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer: applications in personalized medicine. Breast Cancer Res Treat 160(3):411–424

Ali SM, Alpaugh RK, Downing SR, Stephens PJ, Yu JQ, Wu H, Buell JK, Miller VA, Lipson D, Palmer GA, Ross JS, Cristofanilli M (2014) Response of an ERBB2-mutated inflammatory breast carcinoma to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeted therapy. J Clin Oncol 32(25):e88–91

Ali SM, Alpaugh RK, Buell JK, Stephens PJ, Yu JQ, Wu H, Hiemstra CN, Miller VA, Lipson D, Palmer GA, Ross JS, Cristofanilli M (2014) Antitumor response of an ERBB2 amplified inflammatory breast carcinoma with EGFR mutation to the EGFR-TKI erlotinib. Clin Breast Cancer 14(1):e14–16

Fernandez SV, Bingham C, Fittipaldi P, Austin L, Palazzo J, Palmer G, Alpaugh K, Cristofanilli M (2014) TP53 mutations detected in circulating tumor cells present in the blood of metastatic triple negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 16(5):445

Zhang Y, Lu H, Dazin P, Kapila Y (2004) Squamous cell carcinoma cell aggregates escape suspension-induced, p53-mediated anoikis: fibronectin and integrin alphav mediate survival signals through focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem 279(46):48342–48349

Walerych D, Napoli M, Collavin L, Del Sal G (2012) The rebel angel: mutant p53 as the driving oncogene in breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 33(11):2007–2017

Sawaki M, Ito Y, Akiyama F, Tokudome N, Horii R, Mizunuma N, Takahashi S, Horikoshi N, Imai T, Nakao A, Kasumi F, Sakamoto G, Hatake K (2006) High prevalence of HER-2/neu and p53 overexpression in inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer 13(2):172–178

Turpin E, Bieche I, Bertheau P, Plassa LF, Lerebours F, de Roquancourt A, Olivi M, Espie M, Marty M, Lidereau R, Vidaud M, de The H (2002) Increased incidence of ERBB2 overexpression and TP53 mutation in inflammatory breast cancer. Oncogene 21(49):7593–7597

Aas T, Borresen AL, Geisler S, Smith-Sorensen B, Johnsen H, Varhaug JE, Akslen LA, Lonning PE (1996) Specific P53 mutations are associated with de novo resistance to doxorubicin in breast cancer patients. Nat Med 2(7):811–814

Berns EM, Foekens JA, Vossen R, Look MP, Devilee P, Henzen-Logmans SC, van Staveren IL, van Putten WL, Inganas M, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Cornelisse C, Claassen CJ, Portengen H, Bakker B, Klijn JG (2000) Complete sequencing of TP53 predicts poor response to systemic therapy of advanced breast cancer. Cancer Res 60(8):2155–2162

Kandioler-Eckersberger D, Ludwig C, Rudas M, Kappel S, Janschek E, Wenzel C, Schlagbauer-Wadl H, Mittlbock M, Gnant M, Steger G, Jakesz R (2000) TP53 mutation and p53 overexpression for prediction of response to neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 6(1):50–56

Gluck S, Ross JS, Royce M, McKenna EF Jr, Perou CM, Avisar E, Wu L (2012) TP53 genomics predict higher clinical and pathologic tumor response in operable early-stage breast cancer treated with docetaxel-capecitabine ± trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res Treat 132(3):781–791

Wahl AF, Donaldson KL, Fairchild C, Lee FY, Foster SA, Demers GW, Galloway DA (1996) Loss of normal p53 function confers sensitization to Taxol by increasing G2/M arrest and apoptosis. Nat Med 2(1):72–79

Wang Y, Xu Y, Chen J, Ouyang T, Li J, Wang T, Fan Z, Fan T, Lin B, Xie Y (2016) TP53 mutations are associated with higher rates of pathologic complete response to anthracycline/cyclophosphamide-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable primary breast cancer. Int J Cancer 138(2):489–496

Sellers WR, Novitch BG, Miyake S, Heith A, Otterson GA, Kaye FJ, Lassar AB, Kaelin WG Jr (1998) Stable binding to E2F is not required for the retinoblastoma protein to activate transcription, promote differentiation, and suppress tumor cell growth. Genes Dev 12(1):95–106

Whitaker LL, Su H, Baskaran R, Knudsen ES, Wang JY (1998) Growth suppression by an E2F-binding-defective retinoblastoma protein (RB): contribution from the RB C pocket. Mol Cell Biol 18(7):4032–4042

Jiang Z, Jones R, Liu JC, Deng T, Robinson T, Chung PE, Wang S, Herschkowitz JI, Egan SE, Perou CM, Zacksenhaus E (2011) RB1 and p53 at the crossroad of EMT and triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Cycle 10(10):1563–1570

Cancer Genome Atlas N (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490(7418):61–70

Carey L, Winer E, Viale G, Cameron D, Gianni L (2010) Triple-negative breast cancer: disease entity or title of convenience? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 7(12):683–692

Bose R, Kavuri SM, Searleman AC, Shen W, Shen D, Koboldt DC, Monsey J, Goel N, Aronson AB, Li S, Ma CX, Ding L, Mardis ER, Ellis MJ (2013) Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov 3(2):224–237

Greulich H, Kaplan B, Mertins P, Chen TH, Tanaka KE, Yun CH, Zhang X, Lee SH, Cho J, Ambrogio L, Liao R, Imielinski M, Banerji S, Berger AH, Lawrence MS, Zhang J, Pho NH, Walker SR, Winckler W, Getz G, Frank D, Hahn WC, Eck MJ, Mani DR, Jaffe JD, Carr SA, Wong KK, Meyerson M (2012) Functional analysis of receptor tyrosine kinase mutations in lung cancer identifies oncogenic extracellular domain mutations of ERBB2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109(36):14476–14481

Herter-Sprie GS, Greulich H, Wong KK (2013) Activating mutations in ERBB2 and their impact on diagnostics and treatment. Front Oncol 3:86

Rudd ML, Price JC, Fogoros S, Godwin AK, Sgroi DC, Merino MJ, Bell DW (2011) A unique spectrum of somatic PIK3CA (p110alpha) mutations within primary endometrial carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 17(6):1331–1340

Zheng G, Tseng LH, Chen G, Haley L, Illei P, Gocke CD, Eshleman JR, Lin MT (2015) Clinical detection and categorization of uncommon and concomitant mutations involving BRAF. BMC Cancer 15:779

Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Wang R, Ning Y, Hodges L, Gursky A, Siddiqui J, Tomlins SA, Roychowdhury S, Pienta KJ, Kim SY, Roberts JS, Rae JM, Van Poznak CH, Hayes DF, Chugh R, Kunju LP, Talpaz M, Schott AF, Chinnaiyan AM (2013) Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet 45(12):1446–1451

Klein CA (2009) Parallel progression of primary tumours and metastases. Nat Rev Cancer 9(4):302–312

Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K (2012) Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat Rev Cancer 12(5):323–334

Stoecklein NH, Klein CA (2010) Genetic disparity between primary tumours, disseminated tumour cells, and manifest metastasis. Int J Cancer 126(3):589–598

Ignatiadis M, Rothe F, Chaboteaux C, Durbecq V, Rouas G, Criscitiello C, Metallo J, Kheddoumi N, Singhal SK, Michiels S, Veys I, Rossari J, Larsimont D, Carly B, Pestrin M, Bessi S, Buxant F, Liebens F, Piccart M, Sotiriou C (2011) HER2-positive circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 6(1):e15624

Riethdorf S, Muller V, Zhang L, Rau T, Loibl S, Komor M, Roller M, Huober J, Fehm T, Schrader I, Hilfrich J, Holms F, Tesch H, Eidtmann H, Untch M, von Minckwitz G, Pantel K (2010) Detection and HER2 expression of circulating tumor cells: prospective monitoring in breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant GeparQuattro trial. Clin Cancer Res 16(9):2634–2645

Giordano A, Gao H, Anfossi S, Cohen E, Mego M, Lee BN, Tin S, De Laurentiis M, Parker CA, Alvarez RH, Valero V, Ueno NT, De Placido S, Mani SA, Esteva FJ, Cristofanilli M, Reuben JM (2012) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell markers in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 11(11):2526–2534

Swaby RF, Cristofanilli M (2011) Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer: a tool whose time has come of age. BMC Med 9:43

Acknowledgements

We thank Andreas Papoutsis and Erich Klem from Cynvenio Biosystems for the RB1 K720* mutation analysis by NGS, and Francesca Fontana from Menarini Silicon Biosystems for her help with DEPArray protocols. We thank Dr. Jennifer Winn for the revision of patient clinical histories in Supplementary Information. We thank the Fox Chase Cancer Center Sequencing Facility.

Funding

This work was performed under the grant NIH RO1 CA 138239-02 (PI: Cristofanilli).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Paul W. Dempsey is an employee of Cynvenio Biosystems. All remaining authors have declared no competing interests.

Research involving human participants

Patients signed an informed consent and HIPAA certification from the Human Subject Protection Committee prior to sample collection. This study was approved by both the research review committee (RRC) and institutional research board (IRB) at Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bingham, C., Fernandez, S.V., Fittipaldi, P. et al. Mutational studies on single circulating tumor cells isolated from the blood of inflammatory breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 163, 219–230 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4176-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4176-x