Abstract

Soil N availability for plants and microorganisms depends on the breakdown of soil polymers such as proteins into smaller, assimilable units by microbial extracellular enzymes. Changing climatic conditions are expected to alter protein depolymerization rates over the next decades, and thereby affect the potential for plant productivity. We here tested the effect of increased CO2 concentration, temperature, and drought frequency on gross rates of protein depolymerization, N mineralization, microbial amino acid and ammonium uptake using 15N pool dilution assays. Soils were sampled in fall 2013 from the multifactorial climate change experiment CLIMAITE that simulates increased CO2 concentration, temperature, and drought frequency in a fully factorial design in a temperate heathland. Eight years after treatment initiation, we found no significant effect of any climate manipulation treatment, alone or in combination, on protein depolymerization rates. Nitrogen mineralization, amino acid and ammonium uptake showed no significant individual treatment effects, but significant interactive effects of warming and drought. Combined effects of all three treatments were not significant for any of the measured parameters. Our findings therefore do not suggest an accelerated release of amino acids from soil proteins in a future climate at this site that could sustain higher plant productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Plant productivity in temperate, boreal and arctic ecosystems is often constrained by low soil N availability (Vitousek and Howarth 1991). Soil N occurs primarily in polymers that are too large for direct uptake by plants and microorganisms, and soil N availability consequently depends on the breakdown of these polymers into smaller units by microbial extracellular enzymes (Schimel and Bennett 2004). Soil N made available by depolymerization can be taken up by both plants and microorganisms and invested into growth and enzyme synthesis, and N taken up by microorganisms that exceeds the microbial demand is released as ammonium into the soil solution (“N mineralization”; Schimel and Bennett 2004).

The depolymerization of soil proteins into oligopeptides and amino acids is thought to be of particular importance for soil N availability and plant productivity (Schimel and Bennett 2004; Jan et al. 2009), considering that proteins represent the largest fraction of soil N, with smaller contributions from heterocyclic compounds and chitin (Knicker 2011). Amino acids derived from protein depolymerization have been found to dominate the diffusive soil N flux (Inselsbacher and Näsholm 2012), and can be effectively taken up by plants and microorganisms in intact form (Näsholm et al. 2009; Kuzyakov and Xu 2013).

Soil N availability will likely be affected by changing climatic conditions over the next decades. Rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations and temperatures, as well as shifts in precipitation regimes are expected to alter both plant and microbial N demand, and the release of available N from soil polymers. Elevated CO2 has been found to stimulate plant productivity and plant N uptake, as well as activities of extracellular enzymes that target N-bearing soil polymers (Drake et al. 2011; Phillips et al. 2011; Zak et al. 2011). Soil microbial decomposers might thus compensate for the higher plant N uptake under elevated CO2 by investing more resources into extracellular enzymes that break down N-bearing polymers and thereby increase soil N availability (“N mining”; Craine et al. 2007). Microbial N mining under elevated CO2 might be facilitated by higher plant C allocation into roots and root exudates that can stimulate decomposition in general (”priming effect”), and of N-bearing compounds in particular (Drake et al. 2011; Phillips et al. 2011, 2012). Recent modeling studies have emphasized the importance of such a compensating mechanism, and suggested that an increase in plant productivity with rising CO2 concentrations will depend on an increased release of available N from soil organic matter (Grant 2013; Wieder et al. 2015). Supporting such a mechanism, previous meta-analyses have found not only negative (Dieleman et al. 2012), but also neutral (de Graaff et al. 2006) effects of elevated CO2 on indices of soil N availability (inorganic N concentrations, gross and net N mineralization rates), and individual studies have reported even positive effects (Holmes et al. 2006; Hungate et al. 1997).

Warming has also been shown to stimulate plant productivity (Rustad et al. 2001; Wu et al. 2011) and plant N uptake (e.g., An et al. 2005; Boczulak et al. 2014; Jonasson et al. 1999), as well as concentrations of inorganic N, gross and net N mineralization rates (Rustad et al. 2001; Shaw and Harte 2001; Biasi et al. 2008; Dieleman et al. 2012; Bai et al. 2013). These findings suggest that an increase in plant N uptake not only with elevated CO2, but also with warming can be compensated by an increase in the release of available N from soil polymers. An accelerated breakdown of N-bearing polymers might be linked to higher microbial decomposer activity at higher temperature in general, or more specifically to enhanced N mining. Some studies even suggest that observed increases in plant productivity with warming might be mostly indirect effects mediated by increased soil N availability (e.g., Melillo et al. 2011).

In addition to increases in CO2 concentration and temperature, many areas are predicted to experience changes in precipitation patterns such as more frequent drought events (Dai 2011). Drought reduces plant photosynthesis (Chaves et al. 2003) and microbial activity (Borken and Matzner 2009), as well as the diffusion of potential substrates and extracellular enzymes in the soil solution (Borken and Matzner 2009). Drought further promotes the accumulation of often N-bearing osmolytic compounds in microbial cells (Schimel et al. 2007), and can reduce plant N concentrations (He and Dijkstra 2014). Although it has been shown that drought can affect a range of ecosystem properties (Frank et al. 2015), and that these changes can persist long after soil moisture has reached normal levels (Fuchslueger et al. 2016), only minor effects on soil inorganic N concentrations, gross and net N mineralization rates have been reported so far (Emmett et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2011; Auyeung et al. 2013; Fuchslueger et al. 2014).

Although a wide range of studies has described effects of changing environmental conditions on N cycling processes, our ability to predict soil N availability and plant productivity in a future climate is still limited. First, most studies target individual aspects of climate change such as changes in CO2 concentration, warming, and precipitation separately that in reality will co-occur and interact. Multifactorial experiments combining different aspects of climate change are underrepresented, but show that combined effects cannot be deduced from individual effects alone (Larsen et al. 2011; Dieleman et al. 2012). Second, the rate-limiting step for the production of available soil N—the breakdown of N-bearing soil polymers—has rarely been quantified. Instead, changes in the release of available N from soil polymers have been concluded from changes in gross or net N mineralization rates, extractable N concentrations, or extracellular enzymes activities. Previous support for an accelerated release of available N, e.g. with increasing CO2 concentration and temperature, is therefore indirect.

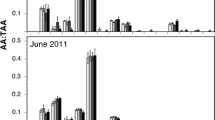

We here directly tested the effect of elevated CO2, warming, and drought, alone and in combination, on gross depolymerization rates of soil proteins into amino acids. We used the multifactorial climate change experiment CLIMAITE that was established in a temperate heathland in Denmark in 2005 and simulated increases in atmospheric CO2 concentration and temperature as well as longer summer droughts as predicted for Denmark in 2075 (Mikkelsen et al. 2008). Previous studies at this site have found that elevated CO2, warming, and drought induced significant changes in plant and soil N pools that point at changes in the release of available N from soil polymers (Fig. 1).

Overview of previously observed treatment effects at the CLIMAITE experimental site. Indicated are significant treatment effects of elevated CO2, elevated temperature, and summer drought on the two dominant plants Deschampsia flexuosa and Calluna vulgaris (AG, aboveground; BG, belowground; Arb. myc., arbuscular mycorrhiza; Eric. myc., ericoid mycorrhiza; DSE, dark septate endophytes), on soil N pools (HFN, heavy soil fraction N; fLFN, free light soil fraction N; DON, dissolved organic N), and on microbial pools and fluxes (Micr. C, microbial C; Micr. N, microbial N; Soil resp., soil respiration; N min., gross N mineralization). Main treatment effects [M] and single treatment effects [S] are indicated separately where they deviate. Main effects describe the significant effect of one treatment by comparing plots that receive this treatment with those that do not (including plots with treatment combinations). Single effects were considered significant when the main effect of a treatment as well as its combination with other treatments was significant. Letters in brackets indicate original references: a, Larsen et al. 2011 (sampling 2007); b, Selsted et al. 2012 (sampling 2005-2008); c, Arndal et al. 2014 (sampling 2008); d, Arndal et al. 2013 (sampling 2010); e, Björsne et al. 2014 (sampling 2010); f, Haugwitz et al. 2014 (sampling 2010); g, Thaysen et al. 2017 (sampling 2013)

Elevated CO2 has been found to increase plant C/N ratios (Larsen et al. 2011; Arndal et al. 2013), root growth (Arndal et al. 2013, 2014), and the belowground plant N stock (Arndal et al. 2013), suggesting enhanced plant N demand and uptake. Nitrogen stocks in the light soil density fraction were significantly reduced (Thaysen et al. 2017), whereas extractable soil N pools remained constant (Larsen et al. 2011), and gross N mineralization rates were constant or even enhanced (Larsen et al. 2011; Björsne et al. 2014). Based on these findings, we hypothesize that elevated CO2 had stimulated gross protein depolymerization rates that provided additional N for plant uptake without reducing N availability for soil microorganisms, resulting in constant or enhanced gross N mineralization rates.

Warming has been shown to increase root growth and the belowground plant N stock in Calluna vulgaris (L.), one of the two dominant plants at the CLIMAITE site (Arndal et al. 2013), as well as N losses from the light and heavy soil fraction (Thaysen et al. 2017), and microbial C and N concentrations (Haugwitz et al. 2014), at constant or enhanced gross N mineralization rates (Larsen et al. 2011; Björsne et al. 2014). We hypothesize that also warming had stimulated gross protein depolymerization rates, promoting the allocation of soil N to microbial and plant biomass at constant or enhanced gross N mineralization rates.

Drought has been found to reduce root biomass and N uptake by Deschampsia flexuosa (L.), the second dominant plant at the CLIMAITE site (Arndal et al. 2014), as well as soil respiration rates (Selsted et al. 2012), at constant or reduced gross N mineralization rates (Larsen et al. 2011; Björsne et al. 2014). These findings indicate a decrease in both plant and microbial activity under drought; we consequently hypothesize that drought had decreased a range of microbial processes including gross protein depolymerization and N mineralization rates. In combination, elevated CO2, warming, and drought led to a deceleration of soil N turnover after the first two years of the experiment, with stronger single treatment than combined treatment effects (Larsen et al. 2011). A more recent study after eight years, however, suggests significant N losses from the light soil fraction after longer exposure to the combined treatments (Thaysen et al. 2017).

To test our hypotheses, we measured gross rates of protein depolymerization into amino acids, as well as N mineralization, microbial amino acid and ammonium uptake using 15N pool dilution assays, and calculated microbial N use efficiency (NUE) based on the measured gross N transformation rates. The fully factorial setup of the experiment permitted us to also test for enhancing or dampening interactive effects of elevated CO2, warming, and drought.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup and soil sampling

The CLIMAITE field experiment was established in 2005 in a temperate heathland in Denmark, ca. 50 km from Copenhagen. The site is characterized by a mean annual temperature of 8 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 613 mm. Dominant plant species are the grass Deschampsia flexuosa (L.) and the evergreen dwarf shrub Calluna vulgaris (L.). The soil is a coarse textured sandy Entisol (Soil Survey Staff 2014) with a ca. 12 cm thick A horizon. pH values (0.01 M CaCl2) are 3.4 and 3.7, respectively, at 0–5 cm and 5–10 cm depth.

Treatments of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration, warming and prolonged summer drought were initiated at this site in a fully factorial design in October 2005, aiming to closely match the climate scenario predicted for Denmark in the year 2075. The experiment consisted of twelve octagons grouped into six experimental blocks, with one octagon per block exposed to elevated CO2, and the other to ambient CO2. Each octagon was split into four plots that were exposed to ambient or increased temperature, and ambient or prolonged summer drought, with all four combinations present in each octagon. In total, the experiment comprised eight different treatment combinations of elevated CO2, warming, and summer drought in a fully factorial design, in six replicates for each treatment. Elevated CO2 was achieved using free air CO2 enrichment (FACE), by injecting CO2 ca. 40 cm above the ground along the perimeter of the octagons. Elevated CO2 concentrations amounted to 510 ppm, and ambient CO2 concentrations to 390 ppm. Temperature was increased with passive night time warming, using curtains 50 cm above the ground that covered the plots at night and thus reflected infrared radiation. Curtains were removed during precipitation events. The warming treatment resulted in an annual soil temperature increase of 0.4 °C at 5 cm depth, ranging from 0.1 °C in winter to 0.7 °C in spring and summer. Summer drought was realized using rain exclusion curtains that were automatically unfolded during summer precipitation events, typically in May or June, and removed 8–11% of the annual precipitation. On average, this resulted in a reduction of soil water content of 3.2 ± 0.5% during the drought period, and of 1.9 ± 0.3% in total (comparison of ambient and drought plots 2006–2013; see Thaysen et al. 2017 for details). In 2013, summer drought was applied from April 29th to May 27th. All treatments were regulated automatically. Site and experimental setup are described in detail in Mikkelsen et al. (2008).

We sampled all 48 experimental plots in November 2013, eight years after the treatments were initiated, and five months after the end of the last artificial summer drought cycle. Sampling was scheduled for November in order to maximize the cumulative effect of as many growing and drought seasons as possible, and to minimize disturbance to the field site by organizing sampling in few, joint campaigns of the groups involved in the CLIMAITE experiment. This restriction also largely excluded the possibility of detailed seasonal studies that require soil sampling. Daily mean soil temperature in November 2013 was 7.6 °C at 5 cm depth in treatments without warming, and 7.8 °C in treatments with warming. Soils were sampled by coring to a depth of 10 cm, and sieved to 2 mm. Water content was determined gravimetrically by drying aliquots at 60 °C, and amounted to an average of 14.1 ± 0.5% of soil dry weight (mean ± standard error across all samples). Drought plots showed lower soil water content (13.4 ± 1.0%) than ambient plots (15.8 ± 1.2%; Table 1); however, the overall drought effect was not statistically significant at the time of sampling five months after the last drought cycle.

Total, extractable, and microbial carbon and nitrogen pools

Total soil organic C and total soil N content were analyzed in dried (60 °C) and ground samples using Elemental Analysis-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (EA-IRMS; CE Instrument EA 1110 elemental analyzer with Finnigan MAT ConFlo II Interface and Finnigan MAT DeltaPlus IRMS). Concentrations of dissolved organic C and total dissolved N, as well as of total free amino acids, ammonium, and nitrate were determined in 0.5 M K2SO4 extracts of fresh soils. For dissolved organic C and total dissolved N, we used a DOC/TN analyzer (Shimadzu TOC-VCPH/CPN/TNM-1), for total free amino acids, we used the fluorometric assay described by Jones et al. (2002), and for ammonium and nitrate, we used the photometric assays described by Kandeler and Gerber (1988) and Miranda et al. (2001), respectively. Dissolved organic N was calculated as the difference between total dissolved N and the sum of ammonium and nitrate. Microbial C and N were estimated using chloroform-fumigation-extraction (Brookes et al. 1985), by fumigating aliquots of fresh soil with chloroform, extracting with 0.5 M K2SO4, and measuring concentrations of dissolved organic C and total dissolved N as described above. Microbial C and N were calculated as differences between fumigated and non-fumigated samples. We note that chloroform fumigation releases mostly cytoplasmic microbial C and N, and that we did not apply a correction factor given the variability of correction factors reported in the literature (Brookes et al. 1985 and the references therein), and that this study focuses on relative treatment effects that would not be affected by a correction factor.

Gross nitrogen transformation rates

Gross rates of protein depolymerization, microbial amino acid uptake, N mineralization, and microbial ammonium uptake were determined in field moist samples using 15N pool dilution assays. The approach is based on labeling the amino acid or ammonium pool in duplicate samples with 15N, incubating for a short period and measuring concentration and isotopic composition of the respective pool in the duplicate samples at two time points. The 15N abundance of amino acids decreases over time as protein depolymerization releases amino acids of natural isotopic abundance, and microorganisms take up amino acids that have the average, 15N-enriched isotopic composition of the pool. Similarly, the 15N abundance of ammonium decreases due to the release of natural abundance ammonium by N mineralization and the uptake of labeled ammonium by microorganisms. Gross production rates of amino acids by protein depolymerization and ammonium by N mineralization, as well as gross consumption rates by microbial amino acid and ammonium uptake can then be calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2), following Kirkham and Bartholomew (1954). The abbreviations t1 and t2 are time points 1 and 2, N1 and N2 the corresponding amino acid or ammonium concentrations, and APE1 and APE2 the corresponding 15N at% excess values of amino acids or ammonium, calculated by subtracting the natural abundance 15N content from the 15N content measured in the samples at the two time points (in at% 15N).

All gross rates were determined at a temperature of 10 °C. In the case of the warming treatments, we therefore consider only long-term adjustments of microbial physiology that were the focus of this study, but not potential short-term effects such as higher enzyme efficiencies. Similarly, drought effects reflect long-term rather than short-term changes given the lack of significant differences in soil water content at the time of sampling five months after the end of the last artificial drought cycle.

For gross protein depolymerization and amino acid uptake rates, we followed the protocol by Wanek et al. (2010), with the modifications described by Wild et al. (2013). We added a solution of 15N labeled amino acids (Spectra and Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, mixture of 20 amino acids of > 98 at% 15N, total concentration 2.4 µg ml−1 dissolved in 10 mM CaSO4, 0.5 ml per sample) to duplicates of 2 g field moist soil, incubated duplicates at 10 °C for 10 or 30 min, respectively, and then extracted samples with 20 ml 10 mM CaSO4 containing 3.7% formaldehyde. Samples were centrifuged, filtered (synthetic wool and GF/C filters; Whatman), loaded on pre-cleaned cation exchange cartridges (Thermo Dionex OnGuard II H 1 cc), and eluted with 10 ml 3 M NH3 for purification of amino acids. Samples were amended with internal standards (1 µg nor-valine, nor-leucine and para-chlorophenylalanine each, Sigma-Aldrich) and dried under N2 before derivatization with ethyl-chloroformate (Wanek et al. 2010) and analysis with GC–MS (Thermo TriPlus Autosampler, Trace GC Ultra and ISQ mass spetrometer, Agilent DB-5 column). Blanks and one set of external standards (1 µg each of 20 amino acids) were processed with the samples throughout the protocol, to correct for background concentrations of amino acids and incomplete recovery from ion exchange cartridges. A second set of external standards (eight concentration levels) was derivatized and analyzed with each batch to calibrate concentrations of alanine, glycine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, threonine, valine, asparagine and aspartate, as well as glutamine and glutamate. The 15N contents of the respective amino acids were calculated from the peak areas of amino acid fragments as described by Wanek et al. (2010).

For gross N mineralization and microbial ammonium uptake rates, we added a solution of 15N labeled (NH4)2SO4 (10 at % 15N, 0.125 mM, 0.5 ml per sample) to duplicates of 2 g field moist soil, and incubated duplicates at 10 °C for 4 or 24 h, respectively. Samples were extracted with 15 ml 2 M KCl and filtered through ash-free cellulose filters (Whatman). Ammonium in the extracts was isolated using acid traps (Sørensen and Jensen 1991), and analyzed with EA-IRMS. Gross rates of protein depolymerization, microbial amino acid uptake, N mineralization and microbial ammonium uptake were calculated as the fluxes into and out of the amino acid and ammonium pool, respectively, using Eqs. (1) and (2).

We finally calculated microbial N use efficiency (NUE) as the proportion of N taken up by microorganisms that was not mineralized, but used for growth and enzyme synthesis. Previous estimates of NUE have considered only microbial amino acid uptake as this was the dominant form of N uptake in these systems (Wild et al. 2013; Mooshammer et al. 2014). We here extend their equation to consider also ammonium uptake that corresponded to 32 ± 6% of amino acid uptake across all samples in our system (mean ± standard error). Microbial NUE was therefore calculated from gross rates of microbial amino acid (AA) and ammonium uptake as well as N mineralization as:

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of treatment effects were conducted in R version 3.3.2 (R Development Core Team 2016). We used Levene’s test in the car package (Fox and Weisberg 2011) to verify homogeneity of variances, and then a linear mixed effect model (lmer in ‘lme4’ package; Bates et al. 2015) to test for treatment effects on measured parameters. The three climate factors (elevated CO2, temperature, drought) and their interactions were used as fixed effects; the experimental split-plot design was incorporated as random effects in the model (block, octagon, octagon x drought, and octagon x temperature; the CO2 treatment is accounted for in the octagon term as CO2 was manipulated at the octagon level). The statistical output from the model was extracted using ANOVA. For all analyses, we considered p-values below 0.05 as significant.

Results

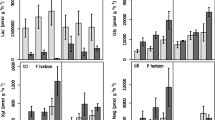

In contrast to our expectations, we found no significant differences in gross protein depolymerization rates between treatments. Average gross protein depolymerization rates across all treatments amounted to 171 ± 13 ng N g−1 dry soil h−1 (mean ± standard error; Fig. 2). Gross microbial amino acid uptake rates were in the same range with on average 167 ± 11 ng N g−1 dry soil h−1. Gross N mineralization rates amounted to 30 ± 4 ng N g−1 dry soil h−1, and corresponded to 18% of gross protein depolymerization rates. Gross microbial ammonium uptake rates were in the same range as gross N mineralization rates, with on average 37 ± 6 ng N g−1 dry soil h−1.

Gross rates of a protein depolymerization, b microbial amino acid uptake, c N mineralization, and d microbial ammonium uptake, as well as e microbial N use efficiency (NUE) after eight years of elevated CO2, elevated temperature (T), and summer drought (D), alone or in combination, in a temperate heathland, as well as in untreated control plots with ambient conditions (A). Bars represent means with standard errors. We tested for significant treatment effects using linear mixed effect models, and indicated effects that were significant at p < 0.05. For NUE, the dashed line represents the maximum NUE of 1

Gross rates of microbial amino acid uptake, N mineralization, and microbial ammonium uptake showed no significant individual effects of elevated CO2, warming, or drought, but significant interactive effects of warming and drought (amino acid uptake: p = 0.023; N mineralization: p = 0.021; ammonium uptake: p = 0.017). This interactive effect implies that amino acid uptake was (non-significantly) lower under warming and drought compared to ambient conditions, but not when both treatments occurred in combination. In contrast, N mineralization and ammonium uptake were (non-significantly) higher under warming, but not when warming occurred in combination with drought (Fig. 2). Amino acid uptake, N mineralization, and ammonium uptake were not significantly affected by eight years of increased atmospheric CO2 concentration, warming, and summer drought combined.

Microbial NUE corresponded to on average 0.85 ± 0.02, indicating that microorganisms allocated 85% of the N taken up as amino acids or ammonium to growth and enzyme production, and released 15% as ammonium by N mineralization. We again found a significant interactive effect of warming and drought (p = 0.047), with (non-significantly) lower NUE under warming and drought, but not when both occurred in combination.

Total organic C and N, microbial C and N, as well as extractable N pools were not significantly affected by any of the treatments (Table 1). Total organic C and N accounted for on average 21.2 ± 0.7 mg C g−1 dry soil and 1.4 ± 0.0 mg N g−1 dry soil, resulting in a C/N ratio of 15.5 ± 0.2. Microbial C and N averaged 221.8 ± 8.8 µg C g−1 dry soil and 22.8 ± 1.0 µg N g−1 dry soil. The extractable soil N pool was dominated by organic N forms, with on average 83 ± 1% in the form of dissolved organic N (13.5 ± 0.4 µg N g−1 dry soil), 13 ± 1% in the form of ammonium (2.2 ± 0.2 µg N g−1 dry soil), and 5 ± 1% in the form of nitrate (0.8 ± 0.1 µg N g−1 dry soil). Dissolved organic C accounted for on average 137.8 ± 3.8 µg C g−1 dry soil and was significantly reduced by the drought treatment (p = 0.049; Table 1).

Discussion

Eight years of elevated CO2, warming, and summer drought, alone or in combination, had not significantly affected gross depolymerization rates of soil proteins into amino acids at our temperate heathland site, sampled at one time point in late fall (Fig. 2). These findings contrast previous studies that indirectly support increased N availability for plants under elevated CO2 and warming at this (Fig. 1) and other experimental sites.

The CLIMAITE experiment was designed to simulate a scenario realistic for the study site in 2075 (Mikkelsen et al. 2008), resulting in moderate climate change treatments compared to other experiments. Elevated and ambient CO2 concentrations differed by ca. 120 ppm at the CLIMAITE site, but typically by ca. 200–400 ppm in other experiments (Dieleman et al. 2012), for instance by 200 ppm in the Duke experimental forest where pronounced differences in N cycling have been observed (Drake et al. 2011; Phillips et al. 2011, 2012). Warming resulted in an average soil temperature increase of 0.4 °C at the CLIMAITE site, compared to ca. 1–5 °C at most other sites (Rustad et al. 2001; Dieleman et al. 2012). Similarly, the drought treatment led to a reduction of annual precipitation by only 8–11% and of soil water content by 1.9%. Intensity and duration of drought, as well as drying-rewetting cycles can affect drought responses of plants and microorganisms (Borken and Matzner 2009; He and Dijkstra 2014). Overall, treatment effects might thus be less pronounced at the CLIMAITE site, but also more realistic. We further point out that our data are based on a one-time sampling campaign in late fall, and that differences between treatments might be more pronounced in other seasons. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown active microbial decomposition (Selsted et al. 2012) and a peak in plant photosynthesis (Albert et al. 2011), as well as treatment effects on gross N mineralization rates (Björsne et al. 2014) and plant N uptake (Arndal et al. 2014) in late fall at the CLIMAITE site.

The direction and magnitude of changes in ecosystem N cycling might further depend on specific ecosystem properties, in particular on the association of plants with mycorrhizal fungi. Ectomycorrhizal fungi have been linked to protein depolymerization (Talbot et al. 2013) and enhanced N mining under elevated CO2 (Terrer et al. 2016), and elevated CO2 has been found to stimulate plant N uptake by promoting fine root biomass, turnover, and exudation in previous studies in ectomycorrhizal forests (Drake et al. 2011; Phillips et al. 2011). The dominant plant species at our site, however, are associated with ericoid and arbuscular mycorrhiza (Arndal et al. 2013). Ericoid mycorrhiza have a proteolytic capacity similar to or even higher than that of ectomycorrhiza (Read and Perez-Moreno 2003), but were not significantly affected by elevated CO2, warming, or summer drought at our study site (Arndal et al. 2013). Arbuscular mycorrhiza, in contrast, were enhanced under elevated CO2 (Arndal et al. 2013), but have a low proteolytic potential (Read and Perez-Moreno 2003). Indirect effects of altered environmental conditions on soil N cycling through changes in mycorrhizal activity are thus unlikely at this heathland site.

In spite of the moderate nature of climate change treatments and specific ecosystem properties, elevated CO2, warming and drought had altered ecosystem N cycling also at the CLIMAITE site, with significant changes in plant, soil and microbial N stocks, plant N uptake and gross N mineralization rates observed in previous studies (Fig. 1), and interactive effects of warming and drought on gross N mineralization, microbial amino acid and ammonium uptake as well as NUE observed in this study (Fig. 2). In contrast to our hypotheses, these changes were not connected to an altered release of amino acids from soil proteins. We here propose two mechanisms that individually or in combination could explain this discrepancy. (1) Elevated CO2, warming and drought might have affected other processes linked to the production of available N forms from soil polymers. For instance, elevated CO2, warming and drought might have altered the incomplete depolymerization of proteins to oligopeptides that can serve as N sources for both plants and microorganisms (e.g., Hill et al. 2011; Farrell et al. 2013), or the depolymerization of other N-bearing soil polymers, such as chitin or heterocyclic compounds. Elevated CO2 has been found to stimulate activities of the chitinolytic enzyme N-acetylglucosaminidase in rhizosphere soils (Phillips et al. 2011), and warming has been suggested to promote the breakdown of heterocyclic N compounds that requires high activation energies (Billings and Ballantyne 2013). (2) Increased plant N uptake under elevated CO2 and temperature might further be facilitated by changes in microbial N demand. The partitioning of N taken up by microorganisms to growth and enzyme synthesis as opposed to N mineralization is described as microbial NUE, and high NUE has been observed in systems of high C, and low N availability, and vice versa (Mooshammer et al. 2014). Warming in particular might have induced a shift from microbial N to C limitation by increasing microbial maintenance respiration (Manzoni et al. 2012), or promoting the breakdown of compounds of high activation energy such as heterocyclic compounds that tend to have low C/N ratios (Billings and Ballantyne 2013). In this case, our estimates of microbial NUE would be disproportionally underestimated in the warming treatment as they consider only amino acids and ammonium as microbial N sources. In any case, since N transformations were measured at 10 °C for all treatments, the observed changes do not reflect short-term fluctuations, e.g., due to higher enzyme efficiencies at higher temperatures (German et al. 2012), but long-term adjustments, mediated by adaptations of the soil microbial community to eight years of warming (Haugwitz et al. 2014).

In summary, we found a surprising resistance of gross protein depolymerization rates to eight years of elevated CO2, warming, and summer drought at a temperate heathland site. While these findings do not rule out changes in protein depolymerization in the initial phase of the experiment, they suggest an adaptation of the microbial community to the altered climatic conditions within less than eight years. Our findings do not suggest that an increase in plant productivity with climate change will be supported by a faster release of amino acids from soil proteins in the long term, at least at this temperate heathland site.

References

Albert KR, Ro-Poulsen H, Mikkelsen TN, Michelsen A, van der Linden L, Beier C (2011) Effects of elevated CO2, warming and drought episodes on plant carbon uptake in a temperate heath ecosystem are controlled by soil water status. Plant Cell Environ 34:1207–1222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02320.x

An Y, Wan S, Zhou X et al (2005) Plant nitrogen concentration, use efficiency, and contents in a tallgrass prairie ecosystem under experimental warming. Glob Chang Biol 11:1733–1744. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01030.x

Arndal MF, Merrild MP, Michelsen A et al (2013) Net root growth and nutrient acquisition in response to predicted climate change in two contrasting heathland species. Plant Soil 369:615–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1601-8

Arndal MF, Schmidt IK, Kongstad J et al (2014) Root growth and N dynamics in response to multi-year experimental warming, summer drought and elevated CO2 in a mixed heathland-grass ecosystem. Funct Plant Biol 41:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP13117

Auyeung DSN, Suseela V, Dukes JS (2013) Warming and drought reduce temperature sensitivity of nitrogen transformations. Glob Change Biol 19:662–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12063

Bai E, Li S, Xu W et al (2013) A meta-analysis of experimental warming effects on terrestrial nitrogen pools and dynamics. New Phytol 199:431–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12252

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Biasi C, Meyer H, Rusalimova O et al (2008) Initial effects of experimental warming on carbon exchange rates, plant growth and microbial dynamics of a lichen-rich dwarf shrub tundra in Siberia. Plant Soil 307:191–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9596-2

Billings SA, Ballantyne F (2013) How interactions between microbial resource demands, soil organic matter stoichiometry, and substrate reactivity determine the direction and magnitude of soil respiratory responses to warming. Glob Change Biol 19:90–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12029

Björsne AK, Rütting T, Ambus P (2014) Combined climate factors alleviate changes in gross soil nitrogen dynamics in heathlands. Biogeochemistry 120:191–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-014-9990-1

Boczulak SA, Hawkins BJ, Roy R (2014) Temperature effects on nitrogen form uptake by seedling roots of three contrasting conifers. Tree Physiol 34:513–523. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpu028

Borken W, Matzner E (2009) Reappraisal of drying and wetting effects on C and N mineralization and fluxes in soils. Glob Change Biol 15:808–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01681.x

Brookes P, Landman A, Pruden G, Jenkinson D (1985) Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: a rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 17:837–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(85)90144-0

Chaves MM, Maroco JP, Pereira JS (2003) Understanding plant responses to drought—from genes to the whole plant. Funct Plant Biol 30:239–264. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP02076

Chen YT, Bogner C, Borken W et al (2011) Minor response of gross N turnover and N leaching to drying, rewetting and irrigation in the topsoil of a Norway spruce forest. Eur J Soil Sci 62:709–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2011.01388.x

Craine JM, Morrow C, Fierer N (2007) Microbial nitrogen limitation increases decomposition. Ecology 88:2105–2113. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1847.1

Dai A (2011) Drought under global warming: a review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 2:45–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.81

de Graaff M-A, van Groenigen K-J, Six J et al (2006) Interactions between plant growth and soil nutrient cycling under elevated CO2: a meta-analysis. Glob Change Biol 12:2077–2091. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01240.x

Dieleman WIJ, Vicca S, Dijkstra FA et al (2012) Simple additive effects are rare: a quantitative review of plant biomass and soil process responses to combined manipulations of CO2 and temperature. Glob Change Biol 18:2681–2693. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02745.x

Drake JE, Gallet-Budynek A, Hofmockel KS et al (2011) Increases in the flux of carbon belowground stimulate nitrogen uptake and sustain the long-term enhancement of forest productivity under elevated CO2. Ecol Lett 14:349–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01593.x

Emmett BA, Beier C, Estiarte M et al (2004) The response of soil processes to climate change: results from manipulation studies of shrublands across an environmental gradient. Ecosystems 7:625–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-004-0220-x

Farrell M, Hill PW, Farrar J et al (2013) Oligopeptides represent a preferred source of organic N uptake: a global phenomenon? Ecosystems 16:133–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9601-8

Fox J, Weisberg S (2011) An R companion to applied regression, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Frank D, Reichstein M, Bahn M et al (2015) Effects of climate extremes on the terrestrial carbon cycle: concepts, processes and potential future impacts. Glob Change Biol 21:2861–2880. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12916

Fuchslueger L, Kastl EM, Bauer F et al (2014) Effects of drought on nitrogen turnover and abundances of ammonia-oxidizers in mountain grassland. Biogeosciences 11:6003–6015. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-6003-2014

Fuchslueger L, Bahn M, Hasibeder R et al (2016) Drought history affects grassland plant and microbial carbon turnover during and after a subsequent drought event. J Ecol 104:1453–1465. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12593

German DP, Marcelo KRB, Stone MM, Allison SD (2012) The Michaelis–Menten kinetics of soil extracellular enzymes in response to temperature: a cross-latitudinal study. Glob Change Biol 18:1468–1479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02615.x

Grant RF (2013) Modelling changes in nitrogen cycling to sustain increases in forest productivity under elevated atmospheric CO2 and contrasting site conditions. Biogeosciences 10:7703–7721. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-7703-2013

Haugwitz MS, Bergmark L, Priemé A et al (2014) Soil microorganisms respond to five years of climate change manipulations and elevated atmospheric CO2 in a temperate heath ecosystem. Plant Soil 374:211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1855-1

He M, Dijkstra FA (2014) Drought effect on plant nitrogen and phosphorus: a meta-analysis. New Phytol 204:924–931. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12952

Hill P, Farrar J, Roberts P et al (2011) Vascular plant success in a warming Antarctic may be due to efficient nitrogen acquisition. Nat Clim Change 1:50–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE1060

Holmes WE, Zak DR, Pregitzer KS, King JS (2006) Elevated CO2 and O3 alter soil nitrogen transformations beneath trembling aspen, paper birch, and sugar maple. Ecosystems 9:1354–1363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-006-0163-5

Hungate BA, Chapin FS, Zhong H et al (1997) Stimulation of grassland nitrogen cycling under darbon dioxide enrichment. Oecologia 109:149–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050069

Inselsbacher E, Näsholm T (2012) The below-ground perspective of forest plants: soil provides mainly organic nitrogen for plants and mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 195:239–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04169.x

Jan MT, Roberts P, Tonheim SK, Jones DL (2009) Protein breakdown represents a major bottleneck in nitrogen cycling in grassland soils. Soil Biol Biochem 41:2272–2282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.08.013

Jonasson S, Michelsen A, Schmidt IK, Nielsen EV (1999) Responses in microbes and plants to changed temperature, nutrient, and light regimes in the Arctic. Ecology 80:1828–1843. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080%5b1828:RIMAPT%5d2.0.CO;2

Jones DL, Owen AG, Farrar JF (2002) Simple method to enable the high resolution determination of total free amino acids in soil solutions and soil extracts. Soil Biol Biochem 34:1893–1902. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00203-1

Kandeler E, Gerber H (1988) Short-term assay of soil urease activity using colorimetric determination of ammonium. Biol Fertil Soils 6:68–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00257924

Kirkham D, Bartholomew WV (1954) Equations for following nutrient transformations in soil, utilizing tracer data. Soil Sci Soc Am J 18:33–34. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1955.03615995001900020020x

Knicker H (2011) Soil organic N—an under-rated player for C sequestration in soils? Soil Biol Biochem 43:1118–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.02.020

Kuzyakov Y, Xu X (2013) Competition between roots and microorganisms for nitrogen: mechanisms and ecological relevance. New Phytol 198:656–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12235

Larsen KS, Andresen LC, Beier C et al (2011) Reduced N cycling in response to elevated CO2, warming, and drought in a Danish heathland: synthesizing results of the CLIMAITE project after two years of treatments. Glob Change Biol 17:1884–1899. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02351.x

Manzoni S, Taylor P, Richter A et al (2012) Environmental and stoichiometric controls on microbial carbon-use efficiency in soils. New Phytol 196:79–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04225.x

Melillo JM, Butler S, Johnson J et al (2011) Soil warming, carbon-nitrogen interactions, and forest carbon budgets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:9508–9512. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1018189108

Mikkelsen TN, Beier C, Jonasson S et al (2008) Experimental design of multifactor climate change experiments with elevated CO2, warming and drought: the CLIMAITE project. Funct Ecol 22:185–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01362.x

Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA (2001) A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide Biol Chem 5:62–71. https://doi.org/10.1006/niox.2000.0319

Mooshammer M, Wanek W, Hämmerle I et al (2014) Adjustment of microbial nitrogen use efficiency to carbon:nitrogen imbalances regulates soil nitrogen cycling. Nat Commun 5:3694. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4694

Näsholm T, Kielland K, Ganeteg U (2009) Uptake of organic nitrogen by plants. New Phytol 182:31–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02751.x

Phillips RP, Finzi AC, Bernhardt ES (2011) Enhanced root exudation induces microbial feedbacks to N cycling in a pine forest under long-term CO2 fumigation. Ecol Lett 14:187–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01570.x

Phillips RP, Meier IC, Bernhardt ES et al (2012) Roots and fungi accelerate carbon and nitrogen cycling in forests exposed to elevated CO2. Ecol Lett 15:1042–1049. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01827.x

R Development Core Team (2016) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Read DJ, Perez-Moreno J (2003) Mycorrhizas and nutrient cycling in ecosystems—a journey towards relevance? New Phytol 157:475–492. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00704.x

Rustad LE, Campbell JL, Marion GM et al (2001) A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia 126:543–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420000544

Schimel JP, Bennett J (2004) Nitrogen mineralization: challenges of a changing paradigm. Ecology 85:591–602. https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8002

Schimel J, Balser TC, Wallenstein M (2007) Microbial stress-response physiology and its implications for ecosystem function. Ecology 88:1386–1394. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0219

Selsted MB, van der Linden L, Ibrom A et al (2012) Soil respiration is stimulated by elevated CO2 and reduced by summer drought: three years of measurements in a multifactor ecosystem manipulation experiment in a temperate heathland (CLIMAITE). Glob Change Biol 18:1216–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02634.x

Shaw MR, Harte J (2001) Response of nitrogen cycling to simulated climate change: differential responses along a subalpine ecotone. Glob Change Biol 7:193–210. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2001.00390.x

Soil Survey Staff (2014) Keys to soil taxonomy, 12th edn. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Washington, DC

Sørensen P, Jensen ES (1991) Sequential diffusion of ammonium and nitrate from soil extracts to a polytetrafluoroethylene trap for 15N determination. Anal Chim Acta 252:201–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2670(91)87215-S

Talbot JM, Bruns TD, Smith DP et al (2013) Independent roles of ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic communities in soil organic matter decomposition. Soil Biol Biochem 57:282–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.10.004

Terrer C, Vicca S, Hungate BA et al (2016) Mycorrhizal association as a primary control of the CO2 fertilization effect. Science 353:72–74. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf4610

Thaysen EM, Reinsch S, Larsen KS, Ambus P (2017) Decrease in heathland soil labile organic carbon under future atmospheric and climatic conditions. Biogeochemistry 133:17–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0303-3

Vitousek PM, Howarth RW (1991) Nitrogen limitation on land and in the sea: how can it occur? Biogeochemistry 13:87–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00002772

Wanek W, Mooshammer M, Blöchl A et al (2010) Determination of gross rates of amino acid production and immobilization in decomposing leaf litter by a novel 15N isotope pool dilution technique. Soil Biol Biochem 42:1293–1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.04.001

Wieder WR, Cleveland CC, Smith WK, Todd-Brown K (2015) Future productivity and carbon storage limited by terrestrial nutrient availability. Nat Geosci 8:441–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2413

Wild B, Schnecker J, Bárta J et al (2013) Nitrogen dynamics in Turbic Cryosols from Siberia and Greenland. Soil Biol Biochem 67:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.08.004

Wu Z, Dijkstra P, Koch GW et al (2011) Responses of terrestrial ecosystems to temperature and precipitation change: a meta-analysis of experimental manipulation. Glob Change Biol 17:927–942. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02302.x

Zak DR, Pregitzer KS, Kubiske ME, Burton AJ (2011) Forest productivity under elevated CO2 and O3: positive feedbacks to soil N cycling sustain decade-long net primary productivity enhancement by CO2. Ecol Lett 14:1220–1226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01692.x

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of the CLIMAITE research center supported by the Villum Kann Rasmussen foundation, Air Liquide Denmark A/S and DONG Energy. Travel support was provided by the INCREASE project (EC FP7-Infrastructure-2008-1 Grant agreement 227628).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Sasha C. Reed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wild, B., Ambus, P., Reinsch, S. et al. Resistance of soil protein depolymerization rates to eight years of elevated CO2, warming, and summer drought in a temperate heathland. Biogeochemistry 140, 255–267 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-018-0487-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-018-0487-1