Abstract

Mesophotic assemblages are the next frontier of marine exploration in the Mediterranean Sea. Located below recreational scuba diving depths, they are difficult to access but host a diverse array of habitats structured by large invertebrate species. The Eastern Mediterranean has been much less explored than the western part of the basin and its mesophotic habitats are virtually unknown. We here describe two mesophotic (77–92 m depth) molluscan assemblages at a rocky reef and on a soft substrate off northern Israel. We record 172 species, of which 43 (25%) are first records for Israel and increase its overall marine molluscan diversity by 7%. Only five of these species have been reported in recent surveys of the nearby Lebanon, suggesting that our results are robust at a broader scale than our study area and that the reported west-to-east declining diversity gradient in the Mediterranean needs a reappraisal based on proper sampling of the eastern basin. We found only four (2%) non-indigenous species, represented by seven (0.5%) specimens. These results suggest that pristine native assemblages still thrive at this depth in Israel, in contrast to the shallow subtidal heavily affected by global warming and biological invasions, calling for strong conservation actions for these valuable but vulnerable habitats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mesophotic ecosystems are located between ~ 40 m and ~ 150 m depth where low light is a dominant abiotic feature (Lesser et al. 2009; Cerrano et al. 2010). Initially defined in tropical areas, this depth zone is increasingly being explored in the Mediterranean Sea uncovering a diverse array of communities dominated by algae (Ballesteros 2006; Bo et al. 2011; Joher et al. 2012), anthozoans (Bo et al. 2009, 2011; Cerrano et al. 2010; Costantini and Abbiati 2016; Grinyó et al. 2016; Corriero et al. 2019; Chimienti et al. 2020), bivalves (Cardone et al. 2020) and sponges (Bo et al. 2011; Idan et al. 2018). Notwithstanding the depth, these communities are under anthropogenic pressure due to stressors such as climate warming (Cerrano et al. 2000; Garrabou et al. 2001, 2009), fishing and trawling (Rossi 2013; Bo et al. 2014). Little is still known about their biodiversity: due to the difficulties of access, most of the surveys focused on the large dominant species. Additionally, with very few exceptions (e.g. Idan et al. 2018) research has been conducted mainly in the western Mediterranean Sea: eastern Mediterranean mesophotic habitats are virtually unknown.

Molluscs are a taxonomically and functionally diverse phylum and some species can be important ecosystem engineers (Gutiérrez et al. 2003). They show a high level of correlation with overall species richness and community patterns on both hard and soft substrates (Ellingsen 2002; Smith 2005). They thrive in all marine habitats, but most species prefer micro-habitats such as crevices, the underneath of stones, plant/algal assemblages or to live infaunally to escape predation (Beesley and Ross 1998; Albano and Sabelli 2012). Molluscs do not represent an exception to the general limited knowledge of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Although some work on native assemblages is available, research has been polarized on the burgeoning number of non-indigenous species, here mostly of Red Sea origin (e.g. Mienis 2010; Albayrak 2011; Crocetta et al. 2017; Steger et al. 2018). Importantly, no work has been conducted on mesophotic molluscs.

We describe the results of recent surveys on two mesophotic (77–92 m depth) assemblages off northern Israel: a rocky reef and a soft substrate. We recorded 172 species, of which 43 (25%) are first records from Israel. Only four species were non-indigenous and suggest that pristine native assemblages still thrive at this depth, in contrast to the shallow subtidal, calling for strong conservation actions for these valuable but vulnerable habitats.

Materials and methods

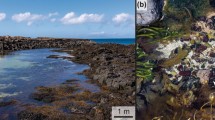

Sampling was conducted at two localities off northern Israel with different substrates: a rocky reef near the western tip of the Rosh Carmel plateau and a soft substrate off Atlit (Fig. 1; Table 1). The rocky reef lies at 92 m depth and had a sponge cover of ~ 40% (Fig. 2). It was sampled at 12 stations with a rock dredge: a steel tube of 20 cm of diameter, provided with a net of mesh size 0.5 cm. The soft substrate was a muddy bottom at 77–83 m depth and was sampled with a Van Veen grab (36.5 × 31.8 cm) collecting three replicates. Samples from both substrates were sieved with a 0.5 mm mesh and fixed in ethanol. Live collected individuals and empty shells were picked in the lab, and stored in ethanol or air dried, respectively. A checklist of the native species of Israel was compiled from the literature: since the first record of a species by Weinkauff (1867), 624 species have been recorded. A screening of the literature shows that 572 species occur in the mesophotic zone (40–150 m). The systematic arrangement follows Bouchet et al. (2017) for the gastropods, Bouchet et al. (2010) for the bivalves and Steiner and Kabat (2001) for the scaphopods. Species authorship is provided in the ESM Table S1.

Sample coverage (completeness) and asymptotic diversity at perfect coverage (= 1) were computed with the iNEXT package after pooling living and dead occurrences per type of substrate (Chao and Jost 2012; Hsieh et al. 2016). The map was drawn with the oceanmap R package.

Shell photographs were taken using a Zeiss SteREO Discovery.V20 stereomicroscope and stacked with Helicon Focus 6, and with a Fei Inspect S50 scanning electron microscope without coating.

Results

We found 135 and 6 living individuals, and 865 and 477 empty shells, on hard and soft substrates, respectively, belonging to 131 and 87 species, for a total of 172 species (ESM Table S1). Sample coverage was very high: 94.5% and 92.3% on hard and soft substrates, respectively, but still, the extrapolated diversity at perfect coverage (= 1) was 193 (+ 51%) and 130 (+ 55%) species (Fig. 3).

Sample completeness (coverage) and estimated richness at perfect coverage at two mesophotic sites off northern Israel. a Sample coverage is very high reaching 94.5% and 92.3% on hard and soft substrates, respectively. b Notwithstanding the high coverage, the extrapolated diversity at perfect coverage is 193 (+ 51%) and 130 (+ 55%) species on hard and soft substrates, respectively

Fourty-three species are here recorded for the first time for Israel: Hanleya hanleyi, Emarginula adriatica, E. tenera, Petalopoma elisabettae, Epitonium tryoni (Fig. 4a–d), Cheirodonta pallescens, Marshallora adversa, Metaxia sp., Pogonodon pseudocanaricus, Similiphora similior, Cerithiopsis pulchresculpta (Fig. 4e, f, j), C. scalaris (Fig. 4g, h, k), Krachia cylindrata (Fig. 4i, l–n), Alvania mamillata, Setia amabilis, Granulina melitensis (Fig. 5a–c), Mitrella coccinea (Fig. 5e–g), Mitrella svelta (Fig. 5d, h), Fusinus buzzurroi, Haedropleura secalina, Mathilda bieleri (Fig. 5i–j), Graphis albida (Fig. 6a–e), Dondice banyulensis (Fig. 2d), Tylodina perversa (Fig. 7i–k), Notodiaphana atlantica (Fig. 5k, l), Pyrunculus hoernesi, Philine punctata (Fig. 7h, l), Odostomella bicincta (Fig. 6f–h), Odostomia sicula, O. turrita (Fig. 6i–m), Parthenina penchynati (Fig. 7a–d), Pyrgulina stefanisi (Fig. 7e–g), Tibersyrnola unifasciata, Crenella pellucida (Fig. 8a–d), Gregariella semigranata, Anadara corbuloides, Asperarca magdalenae (Fig. 7e, f), Parvicardium scabrum, cf. Draculamya porobranchiata (Fig. 8o–s), Kelliopsis jozinae (Fig. 8g–k), Montacuta goudi (Fig. 8l–n), Globivenus effossa and Pitar mediterraneus.

The bivalve we identified as “cf. Draculamya porobranchiata” (Fig. 8o–s) is particularly intriguing. This species has been described from the North-East Atlantic Ocean at bathyal depths and belongs to a peculiar ectoparasitic genus that pierces unidentified hosts and feeds on fluids (Oliver and Lützen 2011). We found it in the reef habitat only. If confirmed, this would be the first record of this species from the Mediterranean Sea.

We also record four (2%) non-indigenous species represented by only seven (0.5%) specimens: Melanella sp. and Parvioris sp. collected alive only and whose taxonomic status will be discussed elsewhere, and Turbonilla cangeyrani and Septifer cumingii collected dead only.

Discussion

Biodiversity novelty in the Israeli mesophotic zone

The mesophotic molluscan diversity of Israel is severely underestimated. Notwithstanding we recorded 131 and 87 species from the hard and soft substrate, respectively, and 43 (25%) species were first records for Israel, diversity estimators suggested that the real diversity may be ~ 50% larger. This is probably the consequence of research mostly focused on shallower waters, difficulties in accessing these habitats, and taxonomic challenges.

Research on coastal benthic biodiversity in Israel was mostly conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, in the context of the 5-year Hebrew University—Smithsonian Institution Joint Program (1967–1972) focused on the Lessepsian invasion (Por et al. 1972) or of other large-scale surveys of benthic assemblages (e.g. Gilat 1964; Galil and Lewinsohn 1981; Tom and Galil 1991). All these endeavours sampled mostly shallow subtidal soft substrates. Further broad-scale sampling has been conducted after the year 2000 in the framework of the National Monitoring Programme. Despite this programme enabled the detection of several non-indigenous species (e.g. Guarnieri et al. 2017), it again targeted mainly soft and hard substrates in shallow water.

Indeed, the mesophotic presents challenges for its sampling and exploration, especially on hard substrates, which can be surveyed most effectively by technical diving or ROVs. The one here described is just the second effort to survey Israeli mesophotic reefs, after the recent exploration of the sponge reefs off Herzlyia, central Israel, at 95–120 m (Idan et al. 2018).

Taxonomic challenges further contribute to diversity underestimation. A paradigmatic example is the hyper-diverse gastropod family Triphoridae (Albano et al. 2011), which until the late 1970s was considered to contain the single Mediterranean species “Triphora perversa” (Piani 1980), but subsequent taxonomic work proved that it is a complex of more than 10 species (Bouchet and Guillemot 1978; Bouchet 1985, 1996). The family was represented in our samples by seven species, five (71%) recorded here for the first time. Further similar cases are the highly diverse Cerithiopsidae and Pyramidellidae, here represented by 5 and 21 species, respectively, of which 3 (60%) and 7 (33%) are new records. A second set of taxonomic cases is related to past misidentifications. It is hard to believe that, e.g., Alvania mamillata, a common rissoid also in shallow waters, has escaped detection since the late nineteenth century. It might have been misidentified by previous authors for A. cimex, from which it has been clearly separated only in the late 1980s (Verduin 1986; Amati et al. 2017). A last case is the one of recently described species belonging to poorly known groups such as Petalopoma elisabettae, Granulina melitensis, Fusinus buzzurroi, Mathilda bieleri, Notodiaphana atlantica, Asperarca magdalenae and cf. Draculamya porobranchiata, all described in the last ~ 20 years, a time that has seen a shrinking of the molluscan taxonomists’ community in Israel as well as an increasing focus on recording Lessepsian species.

As a last remark, we detected only four non-indigenous species, just 2% of the total species richness and 0.5% of the abundance, a result in stark contrast with the dominance of non-indigenous molluscs and other organisms in the shallow subtidal (Edelist et al. 2013; Rilov et al. 2018). Additionally, several native species were represented by large-sized adults, again in contrast with the shallow subtidal, where most species were represented by juveniles which may not reach the reproductive size (Albano et al., results under review). These results suggest that, in Israel, the mesophotic zone still hosts healthy native assemblages, as also noted by Idan et al. (2018). These assemblages lie at much lower temperatures, below 20 °C year around, than the shallow subtidal, where summer temperatures exceed 30 °C (analysis of the GLOBAL_ANALYSIS_FORECAST_PHY_001_024 dataset at https://marine.copernicus.eu/) and may work as climatic refugia because they are less exposed to thermal anomalies and related mass-mortality events (Cerrano et al. 2019). Therefore, they deserve strong conservation measures to protect their diversity, especially in areas like the easternmost Mediterranean Sea where climate warming and biological invasions are profoundly transforming the shallow shelf (Rilov et al. 2020).

Is biodiversity underestimation a broader pattern in the Eastern Mediterranean?

A declining west to east native diversity gradient is reported for the Mediterranean Sea (Tortonese 1951; Coll et al. 2010) as a consequence of its geologic history and the west to east variation in environmental factors (eastward increase in temperature and salinity, and decrease in nutrients in particular) (Sabelli and Taviani 2014). However, part of the reported lower diversity in the Eastern Mediterranean may be attributed to insufficient sampling: every time a taxonomic group is thoroughly studied, a remarkable number of previously unreported native species is recorded (e.g. Morri et al. 2009; Idan et al. 2018; Crocetta et al. 2020; Achilleos et al. 2020; Castelló et al. 2020). Our results are no exception: the 43 newly reported species constitute an increase of 7% in relation to the 624 native molluscs previously recorded from Israel. Importantly, only 5 of these new records have been reported in recent surveys of the nearby Lebanon (Crocetta et al. 2013, 2014, 2020), suggesting that this result is robust over spatial scales broader than our study area.

Natural native biodiversity gradients are, however, being disrupted by the disappearance of native species from the warmest sectors of the Mediterranean Sea (Rilov 2016, Albano et al., results under review). Additionally, the massive entrance of non-indigenous species via the Suez Canal is further profoundly modifying assemblages (Galil 2009; Zenetos et al. 2012; Nunes et al. 2014; Rilov 2016). Proper understanding of the taxonomic and functional changes that these modifications are entailing requires the availability of data on pre-impact conditions. Due to the speed at which such changes are occurring in the Eastern Mediterranean, a thorough basin-scale survey of native biodiversity is mandatory before it is irremediably lost (Peleg et al. 2019; Yeruham et al. 2019).

Data availability

Quantitative data have been deposited in OBIS database.

References

Achilleos K, Jimenez C, Berning B, Petrou A (2020) Bryozoan diversity of Cyprus (eastern Mediterranean Sea): first results from census surveys (2011–2018). Mediterranean Mar Sci 21:228–237. https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.21201

Albano PG, Sabelli B (2012) The molluscan assemblages inhabiting the leaves and rhizomes of a deep water Posidonia oceanica settlement in the central Tyrrhenian Sea. Sci Marina 76:721–732. https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.03396.02C

Albano PG, Sabelli B, Bouchet P (2011) The challenge of small and rare species in marine biodiversity surveys: microgastropod diversity in a complex tropical coastal environment. Biodivers Conserv 20:3223–3237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-011-0117-x

Albayrak S (2011) Alien marine bivalve species reported from Turkish seas. Cah Biol Mar 52:107–118

Amati B, Appolloni M, Smriglio C (2017) Taxonomic notes on the Alvania cimex-complex in the Mediterranean Sea. Alvania cingulata (Philippi, 1836) junior synonym of Alvania mamillata Risso, 1826 (Gastropoda, Rissoidae). Iberus 35:123–141

Ballesteros E (2006) Mediterranean coralligenous assemblages: a synthesis of present knowledge. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev 44:123–195

Beesley PL, Ross GJB (eds) (1998) Mollusca: the southern synthesis. Fauna of Australia. Volume 5. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne

Bo M, Bava S, Canese S et al (2014) Fishing impact on deep Mediterranean rocky habitats as revealed by ROV investigation. Biol Cons 171:167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.01.011

Bo M, Bavestrello G, Canese S et al (2009) Characteristics of a black coral meadow in the twilight zone of the central Mediterranean Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 397:53–61. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08185

Bo M, Bertolino M, Borghini M et al (2011) Characteristics of the mesophotic megabenthic assemblages of the Vercelli Seamount (North Tyrrhenian Sea). PLoS ONE 6:e16357. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016357

Bouchet P (1985) Les Triphoridae de Mediterranee et du proche Atlantique (Mollusca, Gastropoda). Lavori della Società Italiana di Malacol 21:5–58

Bouchet P (1996) Nouvelles observations sur la sistématique des Triphoridae de Méditerranée et du proche Atlantique. Boll Malacol 31:205–220

Bouchet P, Guillemot H (1978) The Triphora perversa-complex in Western Europe. J Molluscan Stud 44:344–356

Bouchet P, Rocroi J-P, Bieler R et al (2010) Nomenclator of bivalve families with a classification of bivalve families. Malacologia 52:1–184

Bouchet P, Rocroi J-P, Hausdorf B et al (2017) Revised classification, nomenclator and typification of gastropod and monoplacophoran families. Malacologia 61:1–526. https://doi.org/10.4002/040.061.0201

Cardone F, Corriero G, Longo C et al (2020) Massive bioconstructions built by Neopycnodonte cochlear (Mollusca, Bivalvia) in a mesophotic environment in the central Mediterranean Sea. Sci Rep 10:6337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63241-y

Castelló J, Bitar G, Zibrowius H (2020) Isopoda (crustacea) from the Levantine sea with comments on the biogeography of Mediterranean isopods. Medit Mar Sci 21:308–339. https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.20329

Cerrano C, Bastari A, Calcinai B et al (2019) Temperate mesophotic ecosystems: gaps and perspectives of an emerging conservation challenge for the Mediterranean Sea. Eur Zool J 86:370–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2019.1677790

Cerrano C, Bavestrello G, Bianchi CN et al (2000) A catastrophic mass-mortality episode of gorgonians and other organisms in the Ligurian Sea (North-western Mediterranean), summer 1999. Ecol Lett 3:284–293. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00152.x

Cerrano C, Danovaro R, Gambi C et al (2010) Gold coral (Savalia savaglia) and gorgonian forests enhance benthic biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in the mesophotic zone. Biodivers Conserv 19:153–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9712-5

Chao A, Jost L (2012) Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation: standardizing samples by completeness rather than size. Ecology 93:2533–2547. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-1952.1

Chimienti G, De Padova D, Mossa M, Mastrototaro F (2020) A mesophotic black coral forest in the Adriatic Sea. Sci Rep 10:8504. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65266-9

Coll M, Piroddi C, Steenbeek J et al (2010) The Biodiversity of the Mediterranean sea: estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 5:e11842. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011842

Corriero G, Pierri C, Mercurio M et al (2019) A Mediterranean mesophotic coral reef built by non-symbiotic scleractinians. Sci Rep 9:3601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40284-4

Costantini F, Abbiati M (2016) Into the depth of population genetics: pattern of structuring in mesophotic red coral populations. Coral Reefs 35:39–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-015-1344-5

Crocetta F, Bitar G, Zibrowius H et al (2014) Biogeographical homogeneity in the eastern Mediterranean Sea: III. New records and a state of the art of Polyplacophora. Scaphopoda Cephalopoda Leban Spix 37:183–206

Crocetta F, Bitar G, Zibrowius H, Oliverio M (2013) Biogeographical homogeneity in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. II. Temporal variation in Lebanese bivalve biota. Aquat Biol 19:75–84. https://doi.org/10.3354/ab00521

Crocetta F, Bitar G, Zibrowius H, Oliverio M (2020) Increase in knowledge of the marine gastropod fauna of Lebanon since the 19th century. Bull Mar Sci 96:22. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2019.0012

Crocetta F, Gofas S, Salas C et al (2017) Local ecological knowledge versus published literature: a review of non-indigenous Mollusca in Greek marine waters. Aquat Invasions 12:415–434

Edelist D, Rilov G, Golani D et al (2013) Restructuring the sea: profound shifts in the world’s most invaded marine ecosystem. Divers Distrib 19:69–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12002

Ellingsen KE (2002) Soft-sediment benthic biodiversity on the continental shelf in relation to environmental variability. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 232:15–27. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps232015

Galil B, Lewinsohn C (1981) Macrobenthic communities of the Eastern Mediterranean continental shelf. Mar Ecol 2:343–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0485.1981.tb00276.x

Galil BS (2009) Taking stock: inventory of alien species in the Mediterranean sea. Biol Invasions 11:359–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-008-9253-y

Garrabou J, Coma R, Bensoussan N et al (2009) Mass mortality in Northwestern Mediterranean rocky benthic communities: effects of the 2003 heat wave. Glob Change Biol 15:1090–1103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01823.x

Garrabou J, Perez T, Sartoretto S, Harmelin JG (2001) Mass mortality event in red coral Corallium rubrum populations in the Provence region (France, NW Mediterranean). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 217:263–272. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps217263

Gilat E (1964) The macrobenthonic invertebrate communities on the Medirerranean continental shelf of Israël. Bulletin de l’Institut Océanographique Monaco 62:1–46

Grinyó J, Gori A, Ambroso S et al (2016) Diversity, distribution and population size structure of deep Mediterranean gorgonian assemblages (Menorca Channel, Western Mediterranean Sea). Prog Oceanogr 145:42–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2016.05.001

Guarnieri G, Fraschetti S, Bogi C, Galil BS (2017) A hazardous place to live: spatial and temporal patterns of species introduction in a hot spot of biological invasions. Biol Invasions 19:2277–2290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1441-1

Gutiérrez JL, Jones CG, Strayer DL, Iribarne OO (2003) Mollusks as ecosystem engineers: the role of shell production in aquatic habitats. Oikos 101:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12322.x

Hsieh TC, Ma KH, Chao A (2016) iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol Evol 7:1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12613

Idan T, Shefer S, Feldstein T et al (2018) Shedding light on an East-Mediterranean mesophotic sponge ground community and the regional sponge fauna. Mediterranean Mar Sci 19:84–106. https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.13853

Joher S, Ballesteros E, Cebrian E et al (2012) Deep-water macroalgal-dominated coastal detritic assemblages on the continental shelf off Mallorca and Menorca (Balearic Islands, Western Mediterranean). Bot Mar 55:485–497. https://doi.org/10.1515/bot-2012-0113

Lesser MP, Slattery M, Leichter JJ (2009) Ecology of mesophotic coral reefs. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 375:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2009.05.009

Mienis HK (2010) Monitoring the invasion of the Eastern Mediterranean by Lessepsian and other Indo-Pacific Molluscs. Haasiana 5:66–68

Morri C, Puce S, Bianchi CN et al (2009) Hydroids (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) from the Levant Sea (mainly Lebanon), with emphasis on alien species. J Mar Biol Ass 89:49–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315408002749

Nunes AL, Katsanevakis S, Zenetos A, Cardoso AC (2014) Gateways to alien invasions in the European seas. Aquat Invasions 9:133–144. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2014.9.2.02

Oliver PG, Lützen J (2011) An anatomically bizarre, fluid-feeding, galeommatoidean bivalve: Draculamya porobranchiata gen. et sp. nov. J Conchol 40:365–392

Peleg O, Guy-Haim T, Yeruham E et al (2019) Tropicalisation may invert trophic state and carbon budget of shallow temperate rocky reefs. J Ecol 108:844–854. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13329

Piani P (1980) Catalogo dei molluschi conchiferi viventi nel Mediterraneo. Boll Malacol 16:113–224

Por FD, Steinitz H, Ferber I, Aron W (1972) The biota of the Red Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean (1967–1972) a survey of the marine life of Israel and surroundings. Isr J Zool 21:459–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/00212210.1972.10688374

Rilov G (2016) Multi-species collapses at the warm edge of a warming sea. Sci Rep 6:36897. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36897

Rilov G, Fraschetti S, Gissi E et al (2020) A fast-moving target: achieving marine conservation goals under shifting climate and policies. Ecol Appl 30:e02009. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2009

Rilov G, Peleg O, Yeruham E et al (2018) Alien turf: Overfishing, overgrazing and invader domination in south-eastern Levant reef ecosystems. Aquat Conserv 28:351–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2862

Rossi S (2013) The destruction of the ‘animal forests’ in the oceans: Towards an over-simplification of the benthic ecosystems. Ocean Coast Manag 84:77–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.07.004

Sabelli B, Taviani M (2014) The making of the Mediterranean molluscan biodiversity. In: Goffredo S, Dubinsky Z (eds) The Mediterranean Sea: Its history and present challenges. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 285–306

Smith SDA (2005) Rapid assessment of invertebrate biodiversity on rocky shores: where there’s a whelk there’s a way. Biodiv Conserv 14:3565–3576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-0828-3

Steger J, Stockinger M, Ivkić A et al (2018) New records of non-indigenous molluscs from the eastern Mediterranean Sea. BioInvasions Rec 7:245–257. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.3.05

Steiner G, Kabat AR (2001) Catalogue of supraspecific taxa of Scaphopoda (Mollusca). Zoosystema 23:433–460

Tom M, Galil B (1991) The macrobenthic associations of Haifa Bay, Mediterranean coast of Israel. Mar Ecol 12:75–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0485.1991.tb00085.x

Tortonese E (1951) I caratteri biologici del Mediterraneo orientale e i problemi relativi. Attualità Zoologiche 7:207–251

Verduin A (1986) Alvania cimex (L.) s.l. (Gastropoda, Prosobranchia) and aggregate species. Basteria 50:25–32

Weinkauff HC (1867) Die Conchylien des Mittelmeeres, ihre geographische und geologisches Verbreitung. Vol. 1., Mollusca Acephalia. T. Fischer, Cassel

Yeruham E, Shpigel M, Abelson A, Rilov G (2019) Ocean warming and tropical invaders erode the performance of a key herbivore. Ecology 101:e02925. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2925

Zenetos Α, Gofas S, Morri C et al (2012) Alien species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2012. A contribution to the application of European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part 2. Introduction trends and pathways. Mediterranean Mar Sci 13:328–352. https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.327

Acknowledgements

The sorting and identification of the material was conducted during a citizen science workshop funded by the Faculty of Earth Sciences, Geography and Astronomy of the University of Vienna. Martin Zuschin offered support throughout the workshop. Bella Galil offered useful suggestions. Jan Steger and the crew of the research vessel “Mediterranean Explorer” helped during fieldwork. We thank the members of the Rilov Lab and the crew of the IOLR’s research vessel “Bat Galim” for collecting and handling the samples in Rosh Carmel. Riccardo Giannuzzi-Savelli, Rafael La Perna, Italo Nofroni, Graham Oliver, Michael Stachowitsch and Carlo Smriglio offered useful advice.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Austrian Science Fund (FWF). Sampling on soft substrates was conducted in the framework of the project “Historical ecology of Lessepsian migration” funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) P28983-B29 (PI: P.G. Albano). Sampling of the hard substrate was conducted in the framework of the Israeli Mediterranean monitoring program conducted by IOLR and funded by the Israeli Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Ministry of Energy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PGA conceived the study. PGA and GR collected the samples. PGA, MA, BA, CB and BS sorted and identified the organisms. PGA wrote a first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpretation and manuscript finalization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

No animal testing was performed during this study.

Sampling and field studies

All necessary permits for sampling and observational field studies have been obtained by the authors from the competent authorities. The study is compliant with CBD and Nagoya protocols.

Additional information

Communicated by Angus Jackson.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article belongs to the Topical Collection: Coastal and marine biodiversity.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Albano, P.G., Azzarone, M., Amati, B. et al. Low diversity or poorly explored? Mesophotic molluscs highlight undersampling in the Eastern Mediterranean. Biodivers Conserv 29, 4059–4072 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02063-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02063-w