Abstract

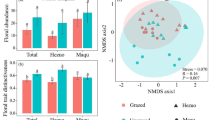

Members of several genera of mites from the family Melicharidae (Mesostigmata) use hummingbirds as transport host to move from flower to flower, where they feed on pollen and nectar. The factors that influence hummingbird flower mite abundance on host plant flowers are not currently known. Here we tested whether hummingbird flower mite abundance on an artificial nectar source is determined by number of hummingbird visits, nectar energy content or species richness of visiting hummingbirds. We conducted experiments employing hummingbird feeders with sucrose solutions of low, medium, and high energy concentrations, placed in a xeric shrubland. In the first experiment, we recorded the number of visiting hummingbirds and the number of visiting hummingbird species, as well as the abundance of hummingbird flower mites on each feeder. Feeders with the highest sucrose concentration had the most hummingbird visits and the highest flower mite abundances; however, there was no significant effect of hummingbird species richness on mite abundance. In the second experiment, we recorded flower mite abundance on feeders after we standardized the number of hummingbird visits to them. Abundance of flower mites did not differ significantly between feeders when we controlled for hummingbird visits. Our results suggest that nectar energy concentration determines hummingbird visits, which in turn determines flower mite abundance in our feeders. Our results do not support the hypothesis that mites descend from hummingbird nostrils more on richer nectar sources; however, it does not preclude the possibility that flower mites select for nectar concentration at other spatial and temporal scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ayasse M, Jarau S (2014) Chemical ecology of bumble bees. Annu Rev Entomol 59:299–319

Boggs CL, Gilbert LE (1987) Spatial and temporal distribution of lantana mites phoretic on butterflies. Biotropica 19:301–305

Colwell RK (1973) Competition and coexistence in a simple tropical community. Am Nat 107:737–760

Colwell RK (1985) Stowaways on the hummingbird express. Nat Hist 94:56–63

Colwell RK (1995) Effects of nectar consumption by the hummingbird flower mite Proctolaelaps kirmsei on nectar availability in Hamelia patens. Biotropica 27:206–217

Colwell RK, Naeem S (1979) The first known species of hummingbird flower mite north of Mexico: Rhinoseius epoecus n. Sp. (Mesostigmata: Ascidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am 72:485–491

Colwell RK, Naeem S (1994) Life history patterns of hummingbird flower mites in relation to host phenology and morphology. In: Houck MA (ed) Mites: ecological and evolutionary analyses of life history patterns. Chapman and Hall, New York, pp 23–44

Crawley MJ (1993) Glim for ecologist. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London

Cutraro JL, Ercelawn AY, LeBrun EG, Lonsdorf EW, Norton HA, McKone MJ (1998) Importance of pollen and nectar in flower choice by hummingbird flower mites, Proctolaelaps kirmsei (Mesostigmata: Ascidae). Int J Acarol 24:345–351

Díaz-Valenzuela R (2008) Análisis descriptivo del sistema colibrí-planta en tres niveles de las escalas espacial, temporal y en la jerarquía ecológica en un paisaje mexicano. Master, Centro Iberoamericano de la Biodiversidad, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo

Dobkin DS (1984) Flowering patterns of long-lived heliconia inflorescences: implications for visiting and residente nectarivores. Oecologia 64:245–254

Dobkin DS (1985) Heterogeneity of tropical floral microclimates and the response of hummingbird flower mites. Ecology 66:536–543

García-Franco GJ, Burgoa DM, Pérez TM (2001) Hummingbird flower mites and Tillandsia spp. (Bromeliaceae): polyphagy in a cloud forest of Veracruz, Mexico. Biotropica 33:538–542

Guerra TJ, Romero GQ, Costa JC, Lofego AC, Benson WW (2012) Phoretic dispersal on bumblebees by bromeliad flower mites (Mesostigmata, Melicharidae). Insecte Sociaux 59:11–16

Hainsworth RF, Wolf LL (1976) Nectar characteristics and food selection by hummingbirds. Oecologia 25:101–113

Heyneman AJ, Colwell RK, Naeem S, Dobkin DS, Hallet B (1991) Host plant discrimination: experiments with hummingbird flower mites. In: Price PW, Lewinsohn TM, Fernandes GW, Benson WW (eds) Plant–animal interactions: evolutionary ecology in tropical and temperate regions. Wiley, New York, pp 455–485

Howell SNG (2003) Hummingbirds of North America the photographic guide. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Krantz GW, Lindquist EE (1979) Evolution of phytophagous mites (Acari). Annu Rev Entomol 24:121–158

Lara C, Ornelas JF (2001) Nectar ‘theft’ by hummingbird flower mites and its consequences for seed set in Moussonia deppeana. Funct Ecol 15:78–84

Mauricio-López E (2005) Interacción colibrí-planta: variación espacial en un matorral xerófito de Hidalgo, México. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo

Naskrecki P, Colwell RK (1998) Systematics and host plant affiliations of hummingbird flower mites of the genera Tropicoseius baker & Yunker and Rhinoseius baker & Yunker (Acari: Mesostigmata: Ascidae). Entomological Society of America

Ortiz-Pulido R, Mauricio-Lopéz E, Martínez-García V, Bravo-Cadena J (eds) (2008) Sabes quien vive en el Parque Nacional El Chico? Colibríes. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Pachuca, Hidalgo, México

Proctor H, Owens I (2000) Mites and birds: diversity, parasitism and coevolution. Trends Ecol Evol 15:358–364

Pyke HG, Waser NM (1981) The production of dilute nectars by hummingbird and honeyeater flowers. Biotropica 13:260–270

Raguso RA (2008) Wake up and smell the roses: the ecology and evolution of floral scent. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 39:549–569

Tschapka M, Cunningham SA (2004) Flower mites of calyptrogyne ghiesbreghtiana (arecaceae): evidence for dispersal using pollinating bats. Biotropica 36:377–381

van Perlo B (2006) Birds of Mexico and Central America. Princeton University Press, Princeton

VSN_International (2011) Genstat for windows, vol 14. VSN International, Hemel Hempstead

Zar JH (1984) Biostatistical analysis, 2nd edn. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Acknowledgments

We thank the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo for its support, Carlos Lara for his comments during the beginning of this project, Nico Bluthgen for suggesting the second experiment, M. Isabel Herrera Juárez and Maria de los Angeles Soto Pineda for field assistance, Richard Feldman for comments on an early version of this paper, Gilberto José de Moraes, Departmento of Entomología e Acarologia, Escola Superior de Agricultura ‘Luiz de Queiroz’, University of Sao Paulo, Piracicaba, Sao Paulo, Brazil for mite identification, and Richard Feldman and Margaret Schroeder for their help improving the English. UML thanks Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología for Grant No. 266931. We are also grateful to Fondos Mixtos-Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología Hidalgo project 191908 ‘Diversidad Biológica del Estado de Hidalgo (tercera etapa)’, and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología project 161702 ‘Mejoramiento y actualización de la infraestructura experimental para proporcionar soporte a los posgrados en Biodiversidad y Conservación de la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo’ for their generous support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Márquez-Luna, U., Vázquez González, M.M., Castellanos, I. et al. Number of hummingbird visits determines flower mite abundance on hummingbird feeders. Exp Appl Acarol 69, 403–411 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-016-0047-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-016-0047-0