Abstract

Work and family are important life domains. This study investigates the relationship between employees’ perceptions of workplace ostracism and their provision of family social support. Integrating social impact theory and self-verification theory, the study provides a novel theoretical framework for examining the influence of workplace ostracism on employees’ provision of family social support. Using a moderated mediation model, it reveals the mediating role of personal reputation and the moderating roles of job social support and perceived organizational support. The results of two three-wave surveys of married employees and their spouses in China demonstrate that the negative relationship between exposure to workplace ostracism and an employee’s provision of family social support is mediated by the employee’s personal reputation. In addition, job social support and perceived organizational support weaken the relationship between personal reputation and family social support and the mediating effect of personal reputation on the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support. The theoretical and managerial implications of this study for human resource management are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ostracism, a universal social phenomenon (Ferris et al., 2015), is the act of isolating an individual or otherwise disconnecting him or her from social interactions. It can include social exclusion, rejection, or abandonment (Ferris et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2013). The perception of workplace ostracism refers to the extent to which an employee perceives that he or she is overlooked, excluded, or ignored by other employees or groups at work (Ferris et al., 2008). Examples of workplace ostracism include: (1) Other employees leave the area when the focal employee enters; (2) Other employees do not invite the focal employee when they go out for a coffee break. Workplace ostracism and its negative impacts on people’s work-related behavior, attitudes, and performance have received increasing attention in recent research (e.g., Ferris et al., 2015; Mao et al., 2018; Peng & Zeng, 2017; Takhsha et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2020). Studies have indicated that the negative effects of workplace ostracism are long-term (Lau et al., 2009; Williams, 2007) and extend beyond the confines of the workplace (Liu et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2020). The work–family nexus is an important component of every society, and the literature has recognized the importance of integrating work and family in studies of the outcomes of workplace ostracism (Choi, 2021; Ferguson et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2020). However, the lack of theoretical frameworks linking these two areas makes it difficult to understand how workplace ostracism affects families (Liu et al., 2013). Few studies have examined the spillover effects of workplace ostracism on employee behavior in the family domain.

Responding to the call by Ferris et al. (2008) to use integrative theoretical frameworks to examine the process underpinning the influence of workplace ostracism, we integrate social impact theory and self-verification theory to identify the complex effects of workplace ostracism on family social support. Social impact theory provides a theoretical lens through which to understand the psychological and pragmatic consequences of workplace ostracism (Latané, 1981). Workplace ostracism separates ostracized employees from others in the social context of the workplace (Wu et al., 2016). Psychologically, workplace ostracism may make the targeted individual doubt his or her value to the organization and may undermine his or her sense of self-worth (Thompson et al., 2020), threatening his or her identity and resulting in negative behaviors such as inaction and disengagement (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Thau et al., 2007). Pragmatically, workplace ostracism can deprive the targeted employees of networks (Brass, 1984), social influence (Pfeffer, 1981), and access to information (Kotter, 1985) within organizations (for a review, see Kwan et al., 2018). These social impacts (i.e., psychological and pragmatic impacts) may undermine the target’s perceptions of his or her own status, importance, and even performance in the workplace (i.e., personal reputation) and negatively influence his or her behavior in the family domain, such as providing family social support.

According to self-verification theory, human actions are naturally directed toward self-verification (Swann, 2012). Individuals consciously strive to preserve and confirm their views and values by engaging in behaviors consistent with those views and values. Empirical evidence has suggested that employees with negative self-perceptions due to ostracism may reduce their work engagement in multiple domains to verify these negative self-perceptions (Ferris et al., 2015; Swann, 2012). Self-verification theory provides a fundamental basis for understanding the role of self-perceptions in the relationship between workplace ostracism and the behavior of ostracized employees.

Social support, or an individual’s perception of his or her access to “helping relationships of varying quality or strength” (Kossek et al., 2011: 291; cf. Viswesvaran et al., 1999), is essential for people to survive and thrive (Bavik et al., 2020). Social support often involves the exchange of resources between at least two persons, such as information, emotional empathy, or tangible assistance (Van Daalen et al., 2006), which are primarily derived from the work and family domains (Bavik et al., 2020). Specifically, social support includes “instrumental aid, emotional concern, informational, and appraisal functions of others in the work (family) domain that are intended to enhance the well-being of the recipient” (Michel et al., 2010: 92). As individuals typically take on different roles in the work and family domains, they can simultaneously provide and receive social support across these two domains (Graven & Grant, 2014; Michel et al., 2010). Although studies have paid much attention to the different roles played by social support (e.g., as an independent predictor, mediator, or moderator) in individual relationships in one’s life domain (see, e.g., Kossek et al., 2011), they have neglected the spillover effects of social support. For example, receiving social support from coworkers and supervisors may influence an employee’s provision of social support to family members, and vice versa.

Family social support has been shown to be positively related to the maintenance of family relationships (Bradbury & Karney, 2004), employee engagement at work (Lapierre et al., 2018), and marital satisfaction (Cramer, 2004), and has been shown to mitigate the contribution of emotional exhaustion to work–family conflict (Booth-LeDoux et al., 2020; Plutt et al., 2018). Family social support requires resources and energy, and research has suggested that workplace ostracism depletes the ostracized individual’s personal resources (Zhu et al., 2017), which could otherwise be used in the family domain to provide social support to family members. According to social impact theory, ostracized individuals (vs. their non-ostracized peers) are more likely to disengage from family social support behaviors due to the psychological and pragmatic effects of workplace ostracism; however, the importance of the negative effect of workplace ostracism on employee behavior in the family domain has not been fully explored (Liu et al., 2013). Given the aforementioned limitations of previous research and the importance of this issue, this study uses an employee’s provision of family social support as the focal outcome variable to examine the spillover effect of workplace ostracism on behavior in the family domain, conditional on the social support received at work. The findings shed light on the predictors of family social support and the relationship between workplace ostracism and the provision of family social support.

We incorporate self-verification theory into our theoretical model to examine the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support by focusing on the mediating role of personal reputation. Reputation has been defined as “a perceptual identity reflective of the complex combination of salient personal characteristics and accomplishments, demonstrated behavior, and intended images presented over some period of time” (Ferris et al., 2003: 213). Based on this definition, Klenke (2007) considered a person’s reputation as the bridge between his or her personal identity and collective identity, because it combines the unique and individual self with the group-oriented aspects of the collective self. At the individual level, a person’s reputation reflects his or her perception of himself or herself as a respected and valued individual; at the collective level, reputation is determined by external groups and reflects a perception shared and agreed upon by others (Klenke, 2007; Zinko et al., 2007). Compared with the individual-level definition, the collective-level definition of reputation has received more research attention. Researchers have explored how attitudes and performance are influenced by reputation at the collective level (Ferris et al., 2003; Hall et al., 2009; Hochwarter et al., 2007; Zinko et al., 2007; Zinko et al., 2012), but we know little about the predictors and outcomes of perceived personal reputation at the individual level (Zinko et al., 2012). Considering the importance of self-perception and self-awareness in guiding behavior (Carlson et al., 2011; Carver, 2011), we propose that personal reputation, as an individual-level identity formed by oneself, is an important bridge between workplace ostracism and family social support. In the workplace, an individual’s perceived personal reputation reflects the extent to which that person thinks or believes that he or she has a good reputation at work (Klenke, 2007; Zinko et al., 2012). In an organization, individuals can understand their reputation by selecting and coding certain aspects of the information obtained from their environment (Emler & Hopkins, 1990) and by adopting behaviors consistent with their perceived reputation to verify and maintain their self-perceptions (Ferris et al., 2015).

The integrated theoretical perspectives of social impact theory and self-verification theory indicate that workplace ostracism can psychologically undermine a targeted individual’s self-esteem and self-confidence while pragmatically preventing him or her from accessing valuable resources in the workplace. Workplace ostracism can negatively affect work performance and therefore the target’s perceived reputation at work. As personal reputation not only reflects how an individual is evaluated and treated by others but also guides that individual’s behavior (Zinko et al., 2007), ostracized individuals, who may have negative self-perceptions due to their weakened personal reputation, may reduce their behavioral inputs in the family domain (e.g., family social support) to verify their negative self-perceptions. By investigating the mechanism that links workplace ostracism to family social support, this study expands our understanding of personal reputation by exploring it as a mediator of the effect of workplace ostracism on an individual’s provision of social support to family members at home.

The contingency perspective on personal reputation posits that reputation is a social construct that cannot be fully understood in isolation from the context in which it occurs. As discussed earlier, from the contingency perspective, workplace social support is a key element of the work environment (Bavik et al., 2020; Turner, 1981). Research has suggested that workplace social support can enhance problem solving (Nielsen et al., 2014), promote organizational commitment and identification (Wiesenfeld et al., 2001), and alleviate employees’ work pressure (e.g., Selvarajan et al., 2013). Abendroth et al. (2012) suggested that different types of social support from different life domains can complement or reinforce each other; thus, receiving social support in the workplace may enhance the recipient’s confidence, and this positive effect is likely to spill over into the recipient’s family domain (Van Yperen & Hagedoorn, 2003; Yang et al., 2018), which may counteract the negative effect of workplace ostracism. Because workplace social support can be an immediately available resource and may alleviate the negative effect of workplace ostracism across different domains, this study adopts the contingency perspective to examine workplace social support as a moderator to better understand the spillover effect of workplace ostracism on the family domain. This approach can shed light on the contingent effect of workplace social support and an individual’s experience as both a recipient and provider of social support. As workplace social support can come from various sources across multiple levels of the organizational hierarchy, from the institutional level (such as organizational policies and practices; Muse & Pichler, 2011) to the individual level (such as supervisors, subordinates, and peers; Bavik et al., 2020; Huffman et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010; Young & Perrewe, 2000), we further distinguish workplace social support by its sources and specifically propose that job social support from supervisors/coworkers and perceived organizational support moderate the association between personal reputation and family social support and the indirect effect of workplace ostracism on family social support via personal reputation. By examining the moderating roles of job social support and perceived organizational support, we respond to the call for research to incorporate different sources of workplace social support to get a more accurate assessment of how social support from distinct sources shapes people’s reactions and outcomes (Bavik et al., 2020).

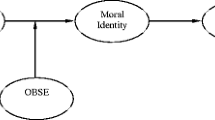

This research makes four contributions to the literature. First, work and family play central and salient roles in an individual’s life (Tang et al., 2014). In view of the significant changes in recent decades, such as the growing number of dual-earner couples (Tang et al., 2014) and the proven positive outcomes of social support in the work and family domains, scholars and practitioners have paid more attention to social support in the field of human resource management. This study contributes to this field by expanding our understanding of the antecedents of family social support behavior and the moderating role of workplace social support, namely job social support and perceived organizational support. Second, we propose a coherent and integrative theoretical framework that includes the selective mechanism of workplace ostracism and its effect on an individual’s behavioral response in the family domain. We also identify the contingent condition in the workplace for this negative effect. Our framework enables us to better understand the nature and behavioral consequences of workplace ostracism beyond the workplace by extending it to the family domain. Third, this research contributes to the literature on workplace ostracism by providing additional understanding of its behavioral outcomes for families. This exploration is meaningful because family social support, as a behavioral outcome, widens the scope of the psychological outcomes of workplace ostracism. This shifts our focus from an individual’s feelings and perceptions to his or her behavioral responses at home. Fourth, this research combines social impact theory and self-verification theory to unpack the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support, and identifies personal reputation as the mechanism that links them. By adopting the integrative theoretical lens of social impact and self-verification, we extend the workplace ostracism–family social support model by highlighting the moderating roles of job social support and perceived organizational support. We then develop and test a moderated mediation model to explain family social support as a behavioral outcome of workplace ostracism. We thus extend the scope of the boundary conditions of workplace ostracism to the effect of personal reputation. We also expand our understanding of the complex nature of workplace ostracism and the behavioral mechanism of workplace ostracism and its behavioral consequences across the work and family domains. These findings can serve as a road map for those interested in investigating workplace ostracism and work–family interfaces and can provide useful guidance for business practitioners and human resource managers. Figure 1 presents our theoretical model examined in Studies 1 and 2.

Theories and hypotheses

Social impact theory and self-verification theory

Social impact theory specifies the effects of others, in particular their behavior, on an individual (Latané, 1981). Latané (1981) defined social impact as “the great variety of changes in physiological states and subjective feelings, motives and emotions, cognitions and beliefs, values and behavior, that occur in an individual” because of the “real, implied, or imagined presence or actions of other individuals” (p. 343). Abundant research has examined the adverse effect of ostracism on fundamental human needs (Thompson et al., 2020; Williams, 1997, 2001), such as the need to belong (Williams et al., 2000), the need for self-esteem (Williams, 2001), the need for control (Zadro et al., 2004), and the need for a meaningful existence (Pyszczynski et al., 2004). People are naturally inclined to build affective bonds for survival, which usually depend on group acceptance and recognition (O’Reilly et al., 2015). People are sensitive and can identify cues or episodic ostracism from others in a social circle, and they can easily feel threatened by these experiences (Spoor & Williams, 2007).

According to social impact theory, the simultaneous threats posed by ostracism to basic human needs have a social impact on all aspects of an individual’s perceptions (e.g., perceived personal reputation) and behaviors (e.g., the provision of social support to family members), either separately or in combination (Thompson et al., 2020; Van Beest & Williams, 2006; Zhang et al., 2017). Williams (1997, 2001) argued that ostracized individuals normally experience simultaneous threats to four fundamental needs—belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence—and are therefore motivated to perform indirect or relational acts to ensure that these needs are met. In addition, given the threats that ostracism poses to basic human needs, ostracized individuals may have a weakened sense of belonging and self-esteem, which may lead to interpersonal deviance and reduced helping behavior toward others (Peng & Zeng, 2017; Thau et al., 2007). The more intense an individual’s experience of workplace ostracism, the greater the threat to that individual’s fundamental needs, the worse his or her perceived personal reputation in the workplace, and the more negative the effect on certain cognitive and behavioral responses. In this study, we adopt social impact theory to develop our theoretical model and explain the intensity of the effect of workplace ostracism on personal reputation and family social support.

To better understand people’s psychological response to intense ostracism, we draw on self-verification theory to explain their behavioral response (i.e., reduced family social support) to workplace ostracism through the mechanism of personal reputation, a perceptual identity that people form about themselves (Klenke, 2007). People are highly motivated to verify their views by engaging in behaviors that are consistent with these views (Kwang & Swann, 2010). According to self-verification theory (Swann, 2012), individuals act in accordance with their self-perceptions, which give them a sense of coherence in everyday life and a sense of predictability in interactions with others. In the social sciences, self-verification theory has been adopted to explain people’s motives for interpersonal and societal outcomes (Swann, 2012). We advance this line of argument and propose that the family can be viewed as a major setting for individual self-verification. Ostracized individuals act in a self-verifying manner and reduce their family social support because of their perceived poor personal reputation. Based on this framework, in conjunction with social impact theory, we develop our hypotheses in the next section.

Workplace ostracism, personal reputation, and family social support

Broadly, workplace ostracism occurs when an individual or group intentionally (e.g., punitively) fails to engage an employee in a work-related situation in which “it is socially appropriate to do so” (Robinson et al., 2013: 206). Workplace ostracism is a form of social disengagement, usually involving inaction rather than action. This characteristic distinguishes it from other harmful social behaviors that require actions or interactions with others (Robinson et al., 2013). Research has shown that the perception of being ignored is strongly related to many undesirable consequences in the workplace, such as distress (Williams, 2007), emotional exhaustion, stress (Howard et al., 2020), disengagement (Craighead et al., 1979), belongingness (Li et al., 2021), and deviant behavior (Balliet & Ferris, 2013; Howard et al., 2020). Although these studies have enriched our understanding of workplace ostracism, research has largely ignored its potential spillover effects on the family domain (Thompson et al., 2020). Recent studies have started to shift the conversation about workplace ostracism toward the work–family interface. Examples are Liu et al. (2013), Choi (2021), and Thompson et al. (2020). However, research on the ripple effect of workplace ostracism on a third party (e.g., focal employees’ spouses) in the family domain is still in its infancy; studies have not yet fully described its mechanism and influence (Ferris et al., 2017; Mao et al., 2018; Sharma & Dhar, 2021; Thompson et al., 2020). We thus focus on focal employees’ provision of social support to their spouses as an outcome of the spillover effect of workplace ostracism on the family domain. By integrating social impact theory and self-verification theory, we argue that people’s perceived reputation in their work environment may be undermined by workplace ostracism and then affect their provision of family social support.

According to Ferris et al. (2003: 213), reputation is “a perceptual identity” formed from the collective perceptions of others, reflecting a complex combination of job competence and the help offered to colleagues (Zinko et al., 2012). Klenke (2007) pointed out that personal reputation has both an individual and a collective component. This study focuses on the individual side of reputation, namely how people perceive themselves as reputable (Klenke, 2007). This focus is consistent with Festinger’s (1954) hypothesis that individuals have an inherent desire to accurately evaluate their own opinions and abilities. Personal reputation is perceptual (Zinko et al., 2007), so individuals can understand their own reputation through the attitudes and behavior reflected back to them by others (Emler & Hopkins, 1990).

In general, workplace ostracism involves the violation of norms regarding acknowledgment, responsiveness, and inclusion (Robinson et al., 2013). According to social impact theory, an employee who is not acknowledged, responded to, or included by other members or groups according to organizational norms may lose opportunities to develop work relationships (Brass, 1984), gain influence (Pfeffer, 1981), or obtain access to information (Kotter, 1985). One of the social impacts of workplace ostracism is to deplete the targeted individual’s work-related resources over time, such as social capital and information (Kwan et al., 2018). Thus, ostracized individuals’ sense of control over their work environment is also reduced as a pragmatic consequence of workplace ostracism (Gerber & Wheeler, 2009). This may lead to inadequate or antisocial responses at work and may prevent the targeted individual from consistently performing at a high level. As personal reputation is a social cognitive construct, lacking the skills necessary for social control over their environment may prevent ostracized individuals from establishing and maintaining a good personal reputation (Zinko, 2010). Moreover, workplace ostracism may convey an implicit message to targeted individuals that they have done something inappropriate or unacceptable (Ferris et al., 2008). When individuals feel ostracized, they perceive negative signals and cues about how others view them and tend to assume that their reputation at work is poor. As discussed above, over the long term, the pragmatic and psychological consequences of workplace ostracism degrade the target’s self-evaluation of his or her own skills and ability to control the work environment or produce high-quality results. As a result, the perceived personal reputation of an ostracized employee may be significantly damaged.

In addition, workplace ostracism is strongly associated with a psychologically distressing and difficult organizational experience (Zadro et al., 2004). Through the self-verification mechanism, ostracized individuals tend to avoid engagement at work, reduce their contributions to the organization, or even withdraw from work to escape the source of their psychological pain (Robinson et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2012). Their reduced levels of contribution to and engagement with the group or organization may undermine their job competency, worsen their already negative self-image, and further trap them in a downward spiral in terms of their perceived personal reputation at work (Zinko et al., 2012). According to the social norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), the psychological impact of workplace ostracism may also lead the targeted employee to display retaliatory behavior. This may exacerbate the situation, as such deviation from normative behavioral patterns at work can damage employees’ perceptions of their personal reputation (Gouldner, 1960; Zinko et al., 2007). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Perceived workplace ostracism is negatively related to personal reputation.

People have an inherent desire to accurately evaluate their own opinions and abilities (Festinger, 1954). This evaluation process involves both individuals’ self-esteem and how others view them (Zinko et al., 2007). Using information received from environmental cues, individuals can form an assessment of their own reputation, which serves the epistemic functions of reducing ambiguity about their personal self-views and of making predictions about the world, as well as the pragmatic function of guiding their behavior (Bozeman & Kacmar, 1997; Swann, 2012).

According to self-verification theory, human behavior has a self-verification purpose (Ferris et al., 2015; Swann, 2012). Once individuals have formed and affirmed their reputation, they seek to engage in behaviors consistent with this reputation to reinforce it and confirm their self-conception (Baumeister & Jones, 1978; Swann et al., 2004; Tsui, 1984). By engaging in such behaviors, they can project specific impressions or images of themselves and achieve a sense of coherence in their lives (Bozeman & Kacmar, 1997; Swann, 2012). Whereas self-enhancement theory suggests that people want to be seen as positively as possible, self-verification theory argues that due to both epistemic and pragmatic considerations, people want to be seen as accurately as possible (Swann, 2012; Yu & Cable, 2011). In addition, self-verification theory argues that ostracized individuals are motivated to verify their pre-existing self-concepts even if being ostracized has caused them to view themselves negatively (Ferris et al., 2015). The motivation to act in a self-verifying manner exists even if a person’s self-concept is negative (Swann, 2012). For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Kwang and Swann (2010) showed that among married people, self-verification striving was stronger than self-enhancement striving. Scholars have argued that a desire for self-verification compels people with negative self-perceptions to solicit negative feedback (Swann et al., 1992) and engage in withdrawal behavior (Ferris et al., 2015) to convince themselves and others of the veracity of their self-concepts, even if this means encouraging others to recognize their shortcomings (Swann, 2012).

This self-verification process can stimulate individuals to actively and intentionally engage in consistent behaviors in all aspects of their lives, including the family domain. According to Swann et al. (2004), people are especially likely to pursue self-verification when they expect to interact with group members for an extended period. Thus, given the importance of the work–family nexus and the long-term nature of personal activities in the family domain, we expect people to be motivated to verify their reputation beyond the workplace by providing social support for family members (Ferguson et al., 2016). Consistent with previous studies (i.e., Ferguson et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2020), we focus on the social support provided by employees to their spouses as a way to verify their self-concepts, namely their personal reputation at work. Family social support is fundamental to the development and well-being of the family (Bavik et al., 2020) and has typically been classified as emotional support (e.g., listening, feedback) and instrumental support (e.g., help with household chores, childcare) (Griggs et al., 2013). Personal reputation at work is related to the focal individual’s qualities, attributes, performance, and success in the work domain (Zinko et al., 2012). When people perceive themselves as having a good reputation at work, they tend to regard themselves as highly competent and skilled—qualities that can be transferred to the family domain to help family members. Such people are motivated to put more effort into providing family social support in an attempt to demonstrate their competence and control. Providing family social support can also be an important impression management tactic, enabling them to influence and enhance their relationships with family members (Huang et al., 2013). The benefits of providing family social support can minimize conflict between focal individuals’ perceived reputation and how they think their family members perceive them, which can further strengthen their perceived personal reputation (Swann, 2012; Zinko et al., 2007). Research supporting self-verification theory has shown that married people with positive self-views feel more committed to their spouses when their spouses evaluate them positively and are more supportive (Swann, 2012). Conversely, individuals with a perceived poor personal reputation are driven by the desire for self-verification, striving to verify their negative self-perceptions by engaging in behaviors consistent with this self-view, such as providing less family social support. People with a perceived poor reputation tend to prefer environments in which they feel ineffectual and rejected, as such environments have become familiar and predictable to them (Shantz & Booth, 2014). To realize a sense of coherence, they are likely to disengage from activities aimed at building and maintaining their personal reputation, such as cooperative and helpful behaviors (Zinko et al., 2012). To confirm to themselves and signal to others their inefficiency and incompetence, they tend to perform poorly in their family roles, such as by failing to provide and rejecting family social support. The resulting negative feedback can further reinforce their negative self-concepts and confirm that family members perceive them as they see themselves. This claim is supported by the literature. For example, Swann et al. (1992) found two interesting results. First, respondents with negative self-concepts tended to seek spouses who evaluated the respondents negatively. Second, respondents were more committed to their spouses when their spouses assessed them negatively than when they evaluated them positively.

According to social impact theory, the social competence and efficacy associated with people’s perceived good personal reputation at work help to improve their social standing (Zinko et al., 2012). Perceiving oneself as valued and respected at work is related to one’s behavioral history in the workplace, such as job competency and helping others (Zinko et al., 2012). Thus, a person’s perceived good personal reputation reflects his or her positive self-evaluations in terms of achievement, status, and value to others. Such a positive perception can trigger positive emotions and enhance perceived legitimacy and trustworthiness (Gioia & Sims, 1983; Ostrom, 2003). These psychological benefits suggest that having a perceived good personal reputation increases one’s access to several resources identified by Hobfoll et al. (1992), including feeling successful, feeling valuable to others, and feeling energetic. Indeed, a perceived good personal reputation at work is itself a valuable but rare resource acquired in the workplace, which can enhance employees’ ability to cope with family issues. The resource value of reputation has been discussed in the literature. For instance, Ferris et al. (2003) adopted the perspective of “capital as metaphor” to argue that reputation can provide individuals with real or potential resources. Individuals who perceive themselves as valued and admired at work are likely to obtain social resources in the work domain (such as skills, qualities, behaviors, and positive psychological states) that may be transferable to the family domain. Work–family enrichment theory also suggests that a sense of accomplishment and personal fulfillment can help an employee to perform better in the family domain (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Therefore, individuals with a perceived good personal reputation at work are likely to transfer the associated social resources from the work domain to the family domain (Zinko et al., 2007) and have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to provide social support to family members. In contrast, individuals with a perceived poor personal reputation have little power and control over important matters (Ferris et al., 2007), lack the competitiveness needed to obtain promotions, lack a sense of identification with others, and have few social connections (Zinko et al., 2007). They are likely to be besieged by negative workplace gossip (Ferris et al., 2007). As a result, these people are likely to have a poor psychological state (e.g., to be defensive and/or diffident) and face the threat of resource depletion.

In summary, individuals with a perceived good (poor) reputation are likely to verify their positive (negative) self-concepts in the family domain by engaging in (disengaging from) family social support. Moreover, compared with a perceived poor personal reputation, a perceived good reputation better equips individuals to maintain a positive psychological state and to obtain the resources necessary to offer family social support. Thus, we argue that a perceived good personal reputation is positively related to the provision of social support to family members in the family domain. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Personal reputation is positively related to family social support.

Our discussion above posits that workplace ostracism damages employees’ perceived personal reputation and that a perceived poor personal reputation reduces an individual’s provision of family social support. Integrating these arguments, we speculate that personal reputation plays a mediating role in the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support. In other words, workplace ostracism negatively affects the personal reputation of an ostracized individual in the workplace, which in turn reduces his or her provision of social support in the family domain.

The literature on work–family interfaces has long suggested that negative experiences at work have destructive effects on employee behavior at home (e.g., Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Recent studies on ostracism have also shown that exposure to ostracism in one domain discourages positive behavior in another domain. In particular, research has indicated that employees’ perceptions of family ostracism reduce their levels of proactive behavior (Ye et al., 2021) and creative behavior at work (Babalola et al., 2021). It is likely that workplace ostracism has negative spillover effects on victims’ behavior at home. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Personal reputation mediates the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support.

Moderating role of job social support

Workplace social support can be physical, verbal, or behavioral. Receiving social support in the workplace not only creates a positive work environment, in which individuals’ fundamental needs can be met, but also enriches their resources at work (Allen, 2001; Behson, 2002), such as information, tangible assistance, and emotional empathy (Kossek et al., 2011; Viswesvaran et al., 1999). As an important contextual factor in the workplace, workplace social support has been widely viewed as a key moderator in the fields of ostracism (Choi, 2021; Kwan et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2014; Williams, 2007) and work–family interfaces (Kossek et al., 2011; Van Daalen et al., 2006). As access to workplace social support can span different levels of the organizational hierarchy and involve both individuals and institutional entities (Bavik et al., 2020; Kossek et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010; Young & Perrewe, 2000), we incorporate workplace social support into our model and respectively examine job social support in Study 1 and perceived organizational support in Study 2 as moderators to better understand the spillover effect of personal reputation.

Job social support refers to the overall levels of informational, instrumental, emotional, and appraisal support received from co-workers and supervisors (Karasek & Theorell, 1990; Michel et al., 2010). As an important job resource, job social support can be provided through positive social interaction and resource exchange between focal individuals and their supervisors or co-workers (Kossek et al., 2011). Although workplace ostracism isolates or disconnects targeted individuals from social interactions (Ferris et al., 2015), they may still perceive a high level of job social support if they receive sufficient work-specific resources from their supervisors or co-workers. For example, being left out or excluded by supervisors may prevent employees from participating in meetings or other daily interactions (Kwan et al., 2018), but they may still receive resources from supervisors or co-workers, such as equipment (e.g., computers) to improve their working conditions and useful information (e.g., a list of customers) to promote their work effectiveness.

When individuals perceive that they have access to job-related resources, they are likely to accumulate work roles (Voydanoff, 2001), buffer stress at work (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000), and transfer positive experiences and resources from the work domain to the family domain (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). In this way, job social support may provide individuals with capital similar to that offered by personal reputation, which they can use to provide social support to their family members (Carlson & Perrewé, 1999). Similarly, job social support can help individuals to meet their role demands at the work–family interface by integrating the two domains, which in turn leads to a positive experience in both domains (Kossek et al., 2011).

In addition, as discussed, family social support may arise from an individual’s strong sense of self-worth and meaningfulness as a result of his or her good personal reputation at work. This contributes to a positive psychological state that could be transferred to the family domain as capital to provide family social support. Job social support can also enhance people’s positive feelings at work (Tang et al., 2014) and sense of belonging, letting them know that their existence has meaning and that they are important to others. Thus, ostracized individuals who have a perceived poor personal reputation but receive job social support at work can still access instrumental, informational, and psychological resources (Van Daalen et al., 2006). Work–family enrichment theory suggests that positive work resources are transferred to the family domain and directly and effectively help recipients of job social support to cope with family issues by providing social support to family members (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Drawing on the substitution perspective (Huang & Zhang, 2013), which suggests that more than one resource can be used to achieve the same goal in a given situation, research has shown that multiple resources can substitute for each other to achieve common employee outcomes (Eby et al., 2015; Kwan et al., 2018). Therefore, as an important resource, job social support substitutes for personal reputation and thus weakens the effect of personal reputation on family social support. Based on these arguments, job social support is likely to lessen the effect of personal reputation on family social support. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Job social support moderates the relationship between personal reputation and family social support, such that the relationship is weaker (stronger) when the level of job social support is high (low).

The above discussion presents an integrated framework in which personal reputation mediates the negative relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support and job social support moderates the relationship between personal reputation and family social support. Based on the moderating role of job social support in the relationship between personal reputation and family social support, and considering that personal reputation is positively associated with workplace ostracism, it is reasonable to suggest that job social support also moderates the strength of the mediating role of personal reputation in the association between workplace ostracism and family social support (a moderated mediation model) (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). As discussed above, we expect a weaker relationship between personal reputation and family social support in an environment with greater job social support. The indirect effect of workplace ostracism on family social support via personal reputation is expected to be weaker in such an environment.

As they are overlooked, excluded, or ignored by others, ostracized individuals may attempt to meet certain psychological needs, such as the need for control or support or the need for self-worth, self-esteem, and relatedness, which have been lost because of workplace ostracism (Gerber & Wheeler, 2009; Williams, 2007). In contrast, job social support can provide employees with important cues signaling their membership of the organization. This can effectively create a self-enhancing environment (Wiesenfeld et al., 2001) in which individuals feel socially included, such that the psychological needs created by workplace ostracism are met to some extent. Consequently, the psychological mechanism of the behavioral response to workplace ostracism (i.e., personal reputation) is weakened in a supportive work environment. The above reasoning suggests that personal reputation mediates the effect of workplace ostracism, such that family social support will be impaired when a high level of job social support is available in the workplace. Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5

Job social support moderates the mediating effect of personal reputation on the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support, such that the mediating effect is weaker (stronger) when the level of job social support is high (low).

Overview of studies

We conducted two field studies to test the hypotheses derived from our research model. In Study 1, we tested Hypotheses 1–5 with three-wave survey data collected from a large commercial bank in China. In particular, we examined the mediating role of personal reputation in the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support and the moderating role of job social support in the relationship between personal reputation and family social support, and in the indirect effect of workplace ostracism on family social support via personal reputation. In Study 2, we sought to accomplish two objectives with data collected from a branch of the People’s Insurance Company of China, a large commercial insurance company in China. First, we aimed to replicate our empirical findings regarding the mediating effect of personal reputation in Study 1 by varying the context and the participants. Using multiple studies and different samples was expected to increase the validity and generalizability of our findings. Second, we examined the moderating role of perceived organizational support in the relationship between personal reputation and family social support and in the indirect effect of workplace ostracism on family social support via personal reputation by replacing job social support with perceived organizational support (Hypotheses 6 and 7 developed later). This helped us explore whether social support at different levels (dyadic vs. organizational) had similar moderating effects.

Study 1: Method

Sample and procedures

The data were collected in a three-wave survey of two sources at a bank in southwest China: employees and their spouses. Two hundred and eighty-eight married employees and their spouses were invited to participate in Study 1. Data collection was conducted in compliance with the Ethics Code of the American Psychological Association (APA). This data collection procedure was also consistent with that used in previous studies on workplace ostracism (e.g., Kwan et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2017). The questionnaires used were paper-based and personally distributed to the participants by one of the researchers. When receiving the questionnaire, the participants also received an information sheet presenting the research objectives and the data collection procedure, and discussing their involvement in the study. Consistent with previous research on ostracism conducted in China (i.e., Liu et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2021), all of the participants were informed that the survey was purely for scientific research purposes and focused on the universal laws of organizational management. We also stressed that participation in the study was voluntary, that no personal details would be collected, and that their identity would not be recorded. The anonymity of the questionnaires ensured the confidentiality and authenticity of the data. As an additional incentive to participate, we provided the participants with feedback on the results of Study 1 after completing data collection and analysis.

We conducted the survey in three waves at two-week intervals to alleviate concerns about common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012). In the first wave (T1), the employees answered questions related to perceived workplace ostracism, their demographic information, and the control variables, including depressed mood. In the second wave (T2), the employees were asked to rate their perceived personal reputation and perceptions of job social support. In the third wave (T3), the employees’ spouses answered questions related to their demographic information and their partner’s family social support. At T1, we distributed 250 questionnaires to the employees and received 222 fully completed questionnaires (a response rate of 88.80%). Two weeks later (T2), we distributed questionnaires to the 222 employees who had completed the survey at T1. All 222 questionnaires were completed and returned in this wave (a response rate of 100%). Finally, two weeks after T2 (T3), we distributed questionnaires to the employees’ spouses via the employees who had completed the T1 and T2 questionnaires. The participating spouses returned their completed questionnaires in sealed envelopes to the researchers by mail. At T3, 222 questionnaires were distributed and 200 were returned (a response rate of 90.09%). The final sample included 200 employee–spouse dyads, for an overall response rate of 80.00%.

Among the 200 employees in our final sample, 59.50% were men. The average age of the participants was 30.31 years (SD = 4.17) and their average number of weekly working hours was 42.27 (SD = 5.13). In terms of education, 8.50% had a postgraduate degree, 53.00% had a Bachelor’s degree, 34.00% had a college diploma, and the remaining 4.50% had completed high school. Among the 200 spouses, the average age of the participants was 29.86 years (SD = 4.37) and 5.50% had a postgraduate degree, 61.00% had a Bachelor’s degree, 31.50% had a diploma from a college, and 2% received high school education.

Measures

Because the participants were Chinese, the survey was administered in Chinese. All of the scales were originally developed in English. Chinese versions of most of the key measures were available in the literature, except for the measure of family social support. To ensure translation equivalence (Brislin, 1980), we used the back-translation method to translate the family social support items from English into Chinese. All of the Likert-type scales were rated from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”).

Workplace ostracism was measured using the 10-item scale originally developed by Ferris et al. (2008) and later applied by Wu et al. (2012) to the Chinese context. A sample item is “Others avoid you at work.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.97. We used the 12-item scale originally developed by Hochwarter et al. (2007) to measure personal reputation, which was later applied by Wu et al. (2013) to the Chinese context. A sample item is “I have a good reputation.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.96. Job social support was measured using the 4-item scale developed by Van Yperen and Hagedoorn (2003) and later applied by Yang et al. (2018) and Zhang et al. (2012) to the Chinese context. Sample items are “If necessary, you can ask your immediate supervisor for help” and “You can rely upon your co-workers when things get tough at work.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.88. Finally, family social support was measured using a 10-item scale (Carlson & Perrewé, 1999). A sample item is “My spouse provides emotional support.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.94.

As negative emotions or moods may affect family role performance (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000), we controlled for depressed mood in our study. We used the 10-item scale originally developed by Quinn and Shepard (1974) and later applied by Wu et al. (2012) to the Chinese context to measure depressed mood. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.95. Due to concerns about the effects of demographic variables on family support (e.g., Liu et al., 2013), we also controlled for employees’ gender, age, education, work hours per week, and number of children, with personal reputation or family social support as the dependent variable. Furthermore, to alleviate concerns about rating and crossover influences, the age and education of the spouses were controlled for when family social support was the dependent variable.

Study 1: Results

To avoid potential attrition effects, we applied the method of Goodman and Blum (1996) to determine whether there were systematic differences in responses. The results of the three multiple logistic regressions indicated that none of the logistic regression coefficients were significant. This provided evidence that the participants who did not complete the three waves of the survey had dropped out randomly.

Confirmatory factor analyses

We performed confirmatory factor analyses using structural equation modeling with Mplus 7.0 to test the convergent and discriminant validity of our key variables. The differences between the five variables (workplace ostracism, personal reputation, job social support, family social support, and depressed mood) were examined by comparing the hypothesized five-factor model with four alternative four-factor models and one one-factor model. As Table 1 shows, the hypothesized five-factor model fit the data well with χ2 (242) = 478.50, p < 0.01, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.96, and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.95. In addition, the four four-factor models and the one-factor model fit the data poorly. These results indicated the discriminant validity of our key variables.

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the key variables. Workplace ostracism was negatively related to personal reputation (r = −0.24, p < 0.01) and family social support (r = −0.22, p < 0.01). Personal reputation was positively related to family social support (r = 0.38, p < 0.01).

Hypothesis testing

We conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses to test our hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 posits that workplace ostracism is negatively associated with personal reputation. Table 3 shows that workplace ostracism was negatively associated with personal reputation (β = −0.22, p < 0.01, Model 2 for personal reputation), supporting Hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2 postulates that personal reputation is positively associated with family social support. Table 3 shows that personal reputation was positively associated with family social support (β = 0.35, p < 0.001, Model 5 for family social support), supporting Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 posits that personal reputation mediates the association between workplace ostracism and family social support. Table 3 shows that the association between workplace ostracism and family social support was significantly negative (β = −0.15, p < 0.05, Model 4 for family social support). After adding personal reputation to the model, the association became non-significant (β = −0.08, n.s., Model 6 for family social support), and personal reputation was positively associated with family social support (β = 0.34, p < 0.001, Model 6 for family social support). We used the PRODCLIN program to test the mediating role of personal reputation in the association between workplace ostracism and family social support (MacKinnon et al., 2007). The results indicated that the confidence interval excluded zero, [−0.140, −0.018], supporting Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4 proposes that job social support moderates the effect of personal reputation on family social support. Table 3 shows that the interaction between personal reputation and job social support was negatively associated with family social support (β = −0.23, p < 0.001, Model 7 for family social support). To understand the moderating role of job social support, we plotted the association between personal reputation and family social support based on two levels of job social support: 1 SD above and below the mean (Aiken & West, 1991). Fig. 2 shows that personal reputation was more positively related to family social support when the level of job social support was low (β = 0.41, p < 0.01) than when it was high (β = 0.06, n.s.), supporting Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 5 proposes that job social support moderates the mediating role of personal reputation in the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support, such that the mediating role is stronger when the level of job social support is low than when it is high. To test Hypothesis 5, we used the bootstrap method with 10,000 samples (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). As shown in Table 4, we found a second-stage moderating role of job social support (∆β = −0.32, p < 0.05), indicating that personal reputation interacted with job social support and that this interaction affected family social support. Hence, Hypothesis 4 was further supported. The results also indicated an indirect moderating effect (∆β = 0.09, p < 0.05), revealing that job social support moderated the mediating effect of personal reputation on the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Study 2: Moderating role of perceived organizational support

Perceived organizational support is defined as the general perception that employees develop concerning “the extent to which the organization values their contribution and cares about their well-being” (Eisenberger et al., 1986: 501). This type of social support reflects the degree to which employees view their organization as both caring and able to offer instrumental and socio-emotional resources when needed (Kossek et al., 2011). Employees who perceive high levels of organizational support are likely to receive important resources, including instrumental, informational, and emotional support (Scott et al., 2014), leading to positive psychological states (Wang & Xu, 2019). Research has conceptually differentiated workplace ostracism from organizational support (for a review, see Ferris et al., 2008). It is possible that an employee receives a low degree of organizational support but at the same time not be ostracized.

Consistent with our arguments regarding the moderating role of job social support, we argue that perceived organizational support can also weaken the relationship between personal reputation and family social support. When employees perceive that they receive support from their organization, they are likely to transfer their positive experiences and resources from the work domain to the family domain (Lapierre et al., 2018). As such, perceived organizational support leads employees to obtain capital similar to that provided by personal reputation, and these employees can use this capital to demonstrate their supportive behavior to family members. In addition, employees with a high level of perceived organizational support tend to have access to instrumental, informational, and psychological resources, which in turn help them feel competent and effective at work, thereby enhancing their positive self-concepts (Scott et al., 2014). As mentioned previously, the substitution perspective posits that multiple resources can substitute for each other to achieve the same goal (Eby et al., 2015; Kwan et al., 2018). Accordingly, perceived organizational support is likely to act as a substitute for personal reputation, weakening the effect of personal reputation on family social support. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6

Perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between personal reputation and family social support, such that this relationship is weaker (stronger) when the level of perceived organizational support is high (low).

As we hypothesize that personal reputation mediates the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support and that perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between personal reputation and family social support, it is reasonable to suggest that perceive organizational support also moderates the strength of the mediating role of personal reputation in the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support. In other words, we predict that the indirect effect of workplace ostracism on family social support via personal reputation is weaker in a positive and caring environment facilitated by perceived organizational support than in a negative and less caring environment low in perceived organizational support. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7

Perceived organizational support moderates the mediating effect of personal reputation on the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support, such that the mediating effect is weaker (stronger) when the level of perceived organizational support is high (low).

Study 2: Method

Sample and procedures

The data were collected from two sources at a branch of the People’s Insurance Company of China in a city in Henan province: employees and their spouses. Four hundred and twenty married employees and their spouses were invited to participate in Study 2. Data collection was conducted in compliance with the APA Ethics Code.

We conducted a three-wave online survey at one-week intervals to alleviate concerns about common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012). In the first wave (T1), the employees answered questions related to their perceived workplace ostracism, demographics, and control variables (e.g., number of working hours per week). In the second wave (T2), the employees were asked to rate their perceived personal reputation and perceived organizational support. In the third wave (T3), the employees’ spouses were asked to evaluate their partner’s family social support. At T1, we distributed 400 questionnaires to the employees and received 390 fully completed questionnaires (a response rate of 97.50%). After checking the quality of the ratings, we retained 385 valid cases. One week later (T2), we distributed questionnaires to the 385 employees who had completed the survey at T1. Three hundred and eighty completed questionnaires were returned in this wave (a response rate of 98.70%). One week after T2 (T3), we sent questionnaires to the employees’ spouses and 375 questionnaires were returned (a response rate of 98.68%). After checking the quality of the ratings, we retained 370 valid questionnaires. The final sample included 370 employee–spouse dyads, for an overall response rate of 92.50%.

Among the 370 employees in our final sample, 78.65% were men. The average age of the participants was 25.64 years (SD = 1.28) and their average number of weekly working hours was 54.47 (SD = 5.03). In terms of education, most of the employees had a community college degree (79.73%) and 20.27% had a Bachelor’s degree.

Measures

We assessed workplace ostracism (α = 0.87), personal reputation (α = 0.83), and family social support (α = 0.70) with the same measures as in Study 1. Perceived organizational support was measured using the eight-item scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (1997) and later applied by Kwan et al. (2018) to the Chinese context. A sample item is “Help is available from management when I have a problem.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study was 0.74.

Due to concerns about the effects of demographic variables on family social support (e.g., Liu et al., 2013), we also controlled for employees’ gender, age, education, job tenure, and working hours per week, with personal reputation or family social support as the dependent variable.

Study 2: Results

To avoid potential attrition effects, we applied the method of Goodman and Blum (1996) to determine whether there were systematic differences in the responses. The results of the three multiple logistic regressions indicated that none of the logistic regression coefficients were significant. This provided evidence that the participants who did not complete the three waves of the survey had dropped out randomly.

Confirmatory factor analyses

We performed confirmatory factor analyses using structural equation modeling with Mplus 7.0 to test the convergent and discriminant validity of our key variables. The differences between the four variables (workplace ostracism, personal reputation, perceived organizational support, family social support) were examined by comparing the hypothesized four-factor model with five alternative three-factor models and one one-factor model. As Table 5 shows, the hypothesized four-factor model fitted the data well, with χ2 (146) = 342.23, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.92, and TLI = 0.90. In addition, the five three-factor models and the one-factor model fitted the data poorly. These results confirmed the discriminant validity of the key variables.

Table 6 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the key variables. Workplace ostracism was negatively related to personal reputation (r = −0.69, p < 0.01) and family social support (r = −0.24, p < 0.01). Personal reputation was positively related to family social support (r = 0.33, p < 0.01).

Hypothesis testing

We conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses to test our hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 posits that workplace ostracism is negatively associated with personal reputation. Table 7 shows that workplace ostracism was negatively associated with personal reputation (β = −0.67, p < 0.001, Model 2 for personal reputation), supporting Hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2 postulates that personal reputation is positively associated with family social support. Table 7 shows that personal reputation was positively associated with family social support (β = 0.31, p < 0.001, Model 5 for family social support), supporting Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 posits that personal reputation mediates the association between workplace ostracism and family social support. Table 7 shows that the association between workplace ostracism and family social support was significantly negative (β = −0.20, p < 0.001, Model 4 for family social support). After adding personal reputation to the model, the association became non-significant (β = −0.01, n.s., Model 6 for family social support), and personal reputation was positively associated with family social support (β = 0.32, p < 0.001, Model 6 for family social support). We used the PRODCLIN program to test the mediating role of personal reputation in the association between workplace ostracism and family social support (MacKinnon et al., 2007). The results indicated that the confidence interval excluded zero, [−0.27, −0.12], supporting Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 6 proposes that perceived organizational support moderates the effect of personal reputation on family social support. Table 7 shows that the interaction between personal reputation and perceived organizational support was negatively associated with family social support (β = −0.42, p < 0.001, Model 7 for family social support). To understand the moderating role of perceived organizational support, we plotted the association between personal reputation and family social support based on two levels of perceived organizational support: 1 SD above and below the mean (Aiken & West, 1991). Figure 3 shows that personal reputation was more positively related to family social support when perceived organizational support was low (β = 0.56, p < 0.001) than when it was high (β = 0.20, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 6.

Hypothesis 7 proposes that perceived organizational support moderates the mediating role of personal reputation in the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support, such that the mediating role is stronger when the level of perceived organizational support is low than when it is high. To test Hypothesis 7, we used the bootstrap method with 10,000 samples (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). As shown in Table 8, we found a second-stage moderating role of perceived organizational support (∆β = −0.86, p < 0.01), indicating that personal reputation interacted with perceived organizational support and that this interaction affected family social support. Hence, Hypothesis 6 was further supported. The results also indicated an indirect moderating effect (∆β = 0.56, p < 0.01), revealing that perceived organizational support moderated the mediating effect of personal reputation on the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support. Thus, Hypothesis 7 was supported.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop an integrative theoretical perspective to explain the association between workplace ostracism and the behavioral response of an ostracized individual in the family domain and to examine the related mechanism and its contingent condition. We focused on the mediating effect of personal reputation and the moderating effects of job social support and perceived organizational support. The findings confirm that due to the pragmatic and psychological impacts of workplace ostracism, workplace ostracism has a detrimental effect on family social support through the personal reputation channel. According to social impact theory, from a pragmatic perspective, when individuals become the target of workplace ostracism, they lose access to resources (including networks, power, status, and key information). From a psychological perspective, ostracized individuals are more likely to reduce their in-role and extra-role performance, contributions, and prosocial behaviors because workplace ostracism robs them of their self-esteem, self-worth, sense of belonging, and even their sense of meaningful existence (Ferris et al., 2008; Williams, 2007). Instead, they tend to engage in antisocial behaviors, are prone to disengagement and inaction, and they may experience depression, exhaustion, or emotional numbness. These psychological and behavioral adaptive responses to workplace ostracism lead ostracized individuals to perceive poor personal reputation, which in turn negatively affects their provision of social support to family members. According to self-verification theory (Swann, 2012), when employees experience workplace ostracism, they may feel unworthy of attention or less important to their organization than other employees. Such a low perception of their personal reputation in the workplace can be further self-verified by reducing their provision of social support in the family domain.

As self-verification theory suggests (Swann, 2012), when individuals are respected or appreciated, they may improve their opinion of themselves and verify that opinion by adopting consistent behaviors. Workplace social support may enable ostracized employees to find alternative sources for the resources depleted by workplace ostracism and alternative ways to fulfill their need to belong. The intensity of the negative emotions created by workplace ostracism may be reduced by directing their attention away from it. In addition, job social support promotes a positive work environment within organizations. With perceived organizational support, ostracized employees may perceive that their organization cares about their well-being and values their existence and contributions (Fuller et al., 2006; Stamper & Masterson, 2002). Thus, both job social support and perceived organizational support can undermine the mediating role of personal reputation in the negative relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support.

Theoretical contributions

This research makes four contributions to the literature on workplace ostracism and work–family interfaces. First, it establishes and empirically tests a theoretical model linking workplace ostracism to family social support. As our empirical findings suggest, the effects of workplace ostracism can extend beyond psychological outcomes (which have received considerable attention in the literature) to behavioral outcomes, and beyond the work domain to the family domain. This extension is important as our model expands the scope of the consequences of workplace ostracism, going beyond concerns about work behaviors and employees’ feelings and psychological states. According to Voydanoff (2009), the work–family nexus should be examined in its entirety to untangle the complexity of the work–family interface. In support of this argument, we propose a unified model of the relationship between workplace ostracism and family social support. Our investigation contributes to the literature on work–family interfaces by identifying the antecedents of family social support in the work domain.

Second, we develop a new integrative theoretical framework to study workplace ostracism and its behavioral response in the family domain by combining social impact theory and self-verification theory. Social impact theory offers a theoretical lens through which to understand the intensity and social impact of workplace ostracism on personal reputation and family social support from a pragmatic and psychological perspective. Self-verification theory provides the theoretical foundations for the mediating role of personal reputation and the moderating roles of job social support and perceived organizational support in these relationships. Taken together, the two theories enable us to holistically unpack their associations by exploring their mechanisms, boundaries, and contingent conditions. Our findings contribute to the limited literature on how workplace ostracism affects behavioral outcomes in the family domain. We also empirically contribute to the development of both theories in terms of how they explain human psychology and behavior.

Third, drawing on social impact theory and self-verification theory, our research investigates both the pragmatic and attitudinal impacts of workplace ostracism and identifies personal reputation as the mechanism by which workplace ostracism negatively affects family social support. Developing and maintaining one’s personal reputation is important (Zinko et al., 2012). Motivated by prior research on the impact of workplace ostracism on self-esteem and self-worth (Robinson et al., 2013), our study identifies the mediating role of personal reputation. This investigation enhances our understanding of the link between workplace ostracism and targeted individuals’ behavioral response in the family domain. Our empirical work unpacks this association and strengthens the theoretical perspectives of social impact and self-verification. Studies of the outcomes associated with personal reputation have largely focused on work-related constructs, such as job satisfaction, turnover intention (Zinko et al., 2012), performance evaluation (Liu et al., 2007), promotion (Blickle et al., 2011), and compensation (Ferris et al., 2003; Kierein & Gold, 2000). Our new theoretical framework provides a broader understanding of personal reputation and its influence on family-related behavioral outcomes, thus expanding the scope of the literature on personal reputation.

Fourth, our examination of the moderating effect of workplace social support (i.e., job social support and perceived organizational support) reveals a complex picture of how workplace ostracism affects the family domain. This enhances our understanding of 1) when employees’ personal reputation in the workplace has a significant impact on their provision of family social support and 2) the contingent condition under which employees reduce their provision of family social support when they are ostracized at work via the personal reputation channel. Our research establishes a theoretical framework for determining the boundary conditions of the effects of workplace ostracism and personal reputation, with an emphasis on social impact and self-verification. In addition, studies have shown that workplace social support can come from different sources, have different targets, and operate at the institutional and individual levels (Bavik et al., 2020; Stinglhamber et al., 2006). Our study advances the understanding of social support by incorporating the sources of workplace social support (i.e., supervisors, co-workers, and the organization) into our model and by simultaneously examining an individual’s experience of workplace social support (as a recipient in the work domain) and family social support (as a provider in the family domain). Our findings regarding the moderating roles of job social support and perceived organizational support strengthen our understanding of how moderated mediation effects can explain the link between workplace ostracism and its consequences. Our exploration of the moderating effect of perceived organizational support also expands our understanding of workplace ostracism and its consequences at both the individual and organizational levels and has implications for organizational practice.

Practical implications

Despite the limitations of our study, our new theoretical model and empirical findings have important practical implications for managers and organizations. Due to the increasing number of family problems in contemporary societies, it is important to pay more attention to work-related issues that may have a significant effect on an individual’s behavior at home (Hammer et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2013). Workplace ostracism is a pervasive social phenomenon (Ferris et al., 2015) and is likely to be common in most organizations (Ferris et al., 2008; Fox & Stallworth, 2005; Robinson et al., 2013). It also has detrimental effects on individuals, and this research highlights its effect on family social support. One of the key practical implications of our results, consistent with the suggestion of Liu et al. (2013), is the need for both employees and organizations to understand the potentially negative effects of workplace ostracism on employee behavior at home. People rely heavily on group membership, recognition, and acceptance for survival (O’Reilly et al., 2015). Many organizations today assume the role of resource provider for their employees (Armeli et al., 1998; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Thus, a direct approach to reducing the frequency of workplace ostracism might be to encourage employees to resolve issues through face-to-face discussions (Williams, 2007) and collaboration (Wu et al., 2015). In addition, training programs on the nature and consequences of workplace ostracism could be organized for management teams and employees (O’Reilly et al., 2015). A zero-tolerance culture to workplace ostracism (Liu et al., 2013) could also be established by developing and implementing relevant policies. Recent research has provided evidence that employees with a high level of self-monitoring (i.e., high self-monitors) are likely to use favor rendering to improve workplace ostracism over time (Wu et al., 2021). Hence, organizations should recommend high self-monitors to engage in favor rendering.