Abstract

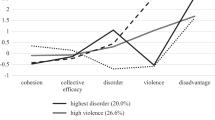

This study examines the direct effects of neighborhood supportive mechanisms (e.g., collective efficacy, social cohesion, social networks) on depressive symptoms among females as well as their moderating effects on the impact of IPV on subsequent depressive symptoms. A multilevel, multivariate Rasch model was used with data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods to assess the existence of IPV and later susceptibility of depressive symptoms among 2959 adult females in 80 neighborhoods. Results indicate that neighborhood collective efficacy, social cohesion, social interactions, and the number of friends and family in the neighborhood reduce the likelihood that females experience depressive symptoms. However, living in areas with high proportions of friends and relatives exacerbates the impact of IPV on females’ subsequent depressive symptoms. The findings indicate that neighborhood supportive mechanisms impact interpersonal outcomes in both direct and moderating ways, although direct effects were more pronounced for depression than moderating effects. Future research should continue to examine the positive and potentially mitigating influences of neighborhoods in order to better understand for whom and under which circumstances violent relationships and mental health are influenced by contextual factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Staff at the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research calculated NC-linked U.S. Census measures in order to ensure the confidentiality of the subjects of the PHDCN.

Although the Community Survey collected information from all 343 NCs about neighborhood conditions via interviews with these residents, this study focuses only on those 80 NCs in which the participants of the LCS were nested.

To arrive at the 2959, a total of 292 cases were deleted due to missing data. The only significant difference between our analysis sample and the eligible sample of female caregivers in a relationship was that our analysis sample had slightly fewer Hispanic women (p < .05). There were no significant differences on the main independent variable of interest or any other control variables.

We control for neighborhood disadvantage in multilevel analyses because, relative to other structural conditions such as residential mobility or ethnic heterogeneity, disadvantage has been found to be the most consistent influence on both IPV and depression (Kim 2008; Mair et al. 2008; Pinchevsky and Wright 2012).

Item response modeling techniques avoid the loss of data from missing responses to a set of questions or indicators (Osgood et al. 2002), take item difficulty into account (i.e., that some indicators of neighborhood constructs may be more difficult and less prevalent than others), and allow simultaneous estimation of the impact of individual-level influences (e.g., age, gender) on perceptions of these constructs (Sampson et al. 2005). The item response models used in this study ultimately provide the neighborhood-level of collective efficacy (or, social cohesion, or social interaction) after these issues have been accounted for.

The same five items that measure social cohesion are also included in the collective efficacy measure. We believe this overlap is conceptually tolerable for the purposes of our inquiry. First, we were interested in the effect of collective efficacy on both depression and the IPV—depression relationship, and thus, needed to include the measure of collective efficacy as it has been examined in prior research (e.g., Sampson et al. 1997). Additionally, there has been some recent attention to the importance of social cohesion with regard to depression (Mair et al. 2010) as well as by itself as a facilitator of positive neighborhood behavior (e.g., informal social control, see Warner 2014). We were interested in its unique effects—apart from collective efficacy—and therefore chose to include a separate measure of social cohesion in our analyses. Collinearity did not present a problem, as we modeled collective efficacy and social cohesion separately.

References

Agoff, C., Herrera, C., & Castro, R. (2007). The weakness of family ties and their perpetuating effects on gender violence: A qualitative study in Mexico. Violence Against Women, 13(11), 1206–1220.

Ahern, J., & Galea, S. (2011). Collective efficacy and major depression in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Epidemiology, 173(12), 1453–1462.

Aneshensel, C. S., & Sucoff, C. A. (1996). The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37(4), 293–310.

Bellair, P. E. (1997). Social interaction and community crime: Examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology, 35(4), 677–704.

Benson, M. L., Fox, G. L., DeMaris, A., & Van Wyk, J. (2003). Neighborhood disadvantage, individual economic distress and violence against women in intimate relationships. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 19(3), 207–235.

Bonomi, A. E., Thompson, R. S., Anderson, M., Reid, R. J., Carrell, D., Dimer, J. A., & Rivara, F. P. (2006). Intimate partner violence and women’s physical, mental, and social functioning. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(6), 458–466.

Browning, C. R. (2002). The span of collective efficacy: Extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 833–850.

Browning, C. R., Feinberg, S. L., & Dietz, R. D. (2004). The paradox of social organization: Networks, collective efficacy, and violent crime in urban neighborhoods. Social Forces, 83(2), 503–534.

Burke, J., O’Campo, P., & Peak, G. L. (2006). Neighborhood influences and intimate partner violence: Does geographic setting matter? Journal of Urban Health, 83(2), 182–194.

Burke, J., O’Campo, P., Salmon, C., & Walker, R. (2009). Pathways connecting neighborhood influences and mental well-being: Socioeconomic position and gender differences. Social Science and Medicine, 68, 1294–1304.

Caetano, R., & Cunradi, C. (2003). Intimate partner violence and depression among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Annals of Epidemiology, 13, 661–665.

Caldwell, J. E., Swan, S. C., & Woodbrown, V. D. (2012). Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychology of Violence, 2(1), 42–57.

Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet, 359(9341), 1331–1336.

Campbell, J. C., Kub, J. E., & Rose, L. (1996). Depression in battered women. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 51(3), 106–110.

Cerda, M., Sanchez, B. N., Galea, S., Tracy, M., & Buka, S. L. (2008). Estimating co-occuring behavioral trajectories within a neighborhood context: A case study of multivariate transition models for clustered data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 168(10), 1190–1203.

Coker, A. L., Davis, K. E., Arias, I., Desai, R. A., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H. M., & Smith, P. H. (2002a). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23(4), 260–268.

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., Thompson, M. P., McKeown, R. E., Bethea, L., & Davis, K. E. (2002b). Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 11(5), 465–476.

Cunradi, C. (2010). Neighborhoods, alcohol outlets and intimate partner violence: Addressing research gaps in explanatory mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7, 799–813.

DeMaris, A., & Kaukinen, C. (2005). Violent victimization and women’s mental and physical health: Evidence from a national sample. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 42(4), 384–411.

Earls, F. J., Brooks-Gunn, J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Sampson, R. J. (2002). Project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods (PHDCN). Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Corsortium for Political and Social Research.

Echeverria, S., Diez Roux, A. V., Shea, S., Borrell, L. N., & Jackson, S. (2008). Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Health & Place, 14(4), 853–865.

Edwards, K. M., Mattingly, M. J., Dixon, K. J., & Banyard, V. L. (2014). Community matters: Intimate partner violence among rural young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 198–207.

Emery, C. R., Jolley, J. M., & Wu, S. (2011). Desistance from intimate partner violence: The role of legal cynicism, collective efficacy, and social disorganization in Chicago neighborhoods. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48, 373–383.

Fletcher, J. (2010). The effects of intimate partner violence on health in young adulthood in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 130–135.

Geis, K. J., & Ross, C. E. (1998). A new look at urban alienation: The effect of neighborhood disorder on perceived powerlessness. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61(3), 232–246.

Golding, J. M. (1999). Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 14(2), 99–132.

Goodman, L. A., Smyth, K. F., Borges, A. M., & Singer, R. (2009). When crises collide: How intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping? Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(4), 306–329.

Hadeed, L. F., & El-Bassel, N. (2006). Social support among Afro-Trinidadian women experiencing intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 12(8), 740–760.

Hill, T. D., Ross, C. E., & Angel, R. J. (2005). Neighborhood disorder, psychophysiological distress, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(2), 170–186.

Johnson, W. L., Giordano, P. C., Longmore, M. A., & Manning, W. D. (2014). Intimate partner violence and depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 39–55.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Mroczerk, D., Ustun, B., & Wittchen, H.-U. (1998). The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short-form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7(4), 171–185.

Kim, D. (2008). Blues from the neighborhood? Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30, 101–117.

Kim, J. (2010). Neighborhood disadvantage and mental health: The role of neighborhood disorder and social relationships. Social Science Research, 39(2), 260–271.

Kim, J., & Ross, C. E. (2009). Neighborhood-specific and general social support: Which buffers the effect of neighborhood disorder on depression? Journal of Community Psychology, 37(6), 725–736.

Kirk, D. S., & Matsuda, M. (2011). Legal cynicism, collective efficacy, and the ecology of arrest. Criminology, 49(2), 443–472.

Kirst, M., Lazgare, L. P., Zhang, Y. J., & O’Campo, P. (2015). The effects of social capital and neighborhood characteristics on intimate partner violence: A consideration of social resources and risks. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 314–325.

Kornhauser, R. R. (1978). Social sources of delinquency: An appraisal of analytic models. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Latkin, C. A., & Curry, A. D. (2003). Stressful neighborhoods and depression: A prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(1), 34–44.

Mair, C., Diez Roux, A. V., & Galea, S. (2008). Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(11), 940–946.

Mair, C., Diez Roux, A. V., & Morenoff, J. D. (2010). Neighborhood stressors and social support as predictors of depressive symptoms in the Chicago Community Adult Health Study. Health & Place, 16(5), 811–819.

Miles-Doan, R. (1998). Violence between spouses and intimates: Does neighborhood context matter? Social Forces, 77(2), 623–645.

Moe, A. M. (2007). Silenced voices and structured survival: Battered women’s help seeking. Violence Against Women, 13(7), 676–699.

Molnar, B. E., Cerda, M., Roberts, A. L., & Buka, S. L. (2008). Effects of neighborhood resources on aggressive and delinquent behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 1086–1093.

Molnar, B. E., Miller, M. J., Azrael, D., & Buka, S. L. (2004). Neighborhood predictors of concealed firearm carrying among children and adolescents: Results from the project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 158(7), 657–664.

Morenoff, J. D., Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2001). Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology, 39(3), 517–559.

O’Campo, P., Burke, J., Peak, G. L., McDonnell, K. A., & Gielen, A. C. (2005). Uncovering neighbourhood influence on intimate partner violence using concept mapping. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(7), 603–608.

Osgood, D. W., McMorris, B. J., & Potenza, M. T. (2002). Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance I: Item response theory scaling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18, 267–296.

Pinchevsky, G. M., & Wright, E. M. (2012). The impact of neighborhoods on intimate partner violence and victimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(2), 112–132.

Raudenbush, S. W., Johnson, C., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). A multivariate, multilevel Rasch model with application to self-reported criminal behavior. Sociological Methodology, 33(1), 169–211.

Rios, R., Aiken, L. S., & Zautra, A. J. (2012). Neighborhood contexts and the mediating role of neighborhood social cohesion on health and psychological distress among Hispanic and non-Hispanic residents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 43(1), 50–61. doi:10.1007/s12160-011-9306-9.

Ross, C. E. (2000). Neighborhood disadvantage and adult depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(2), 177–187.

Ross, C. E., & Jang, S. J. (2000). Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: The buffering role of social ties with neighbors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(4), 401–420.

Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (2009). Neighborhood disorder, subjective alienation, and distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 49–64. doi:10.1177/002214650905000104.

Ross, C. E., Mirowsky, J., & Pribesh, S. (2001). Powerless and the amplification of threat: Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. American Sociological Review, 66(4), 568–591.

Ross, C. E., Reynolds, J. R., & Geis, K. J. (2000). The contingent meaning of neighborhood stability for residents’ psychological well-being. American Sociological Review, 65(4), 581–597.

Sampson, R. J. (2003). The neighborhood context of well being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3), S53–S73.

Sampson, R. J. (2013). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2005). Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparaties in violence. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 224–232.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. J. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas: A study of rates of delinquents in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Stafford, M., McMunn, A., & De Vogli, R. (2011). Neighbourhood social environment and depressive symptoms in mid-life and beyond. Ageing & Society, 31(6), 893–910.

Stith, S. M., Smith, D. B., Penn, C. E., Ward, D. B., & Tritt, D. (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(1), 65–98.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and Family, 41(1), 75–88.

Straus, M. A., Gelles, R. J., & Steinmetz, S. K. (2006). Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Taylor, S. E., & Repetti, R. L. (1997). Health psychology: What is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 411–447.

Van Wyk, J. A., Benson, M. L., Fox, G. L., & DeMaris, A. (2003). Detangling individual-, partner-, and community-level correlates of partner violence. Crime & Delinquency, 49(3), 412–438.

Vega, W. A., Ang, A., Rodriguez, M. A., & Finch, B. K. (2011). Neighborhood protective effects on depression in Latinos. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1–2), 114–126.

Warner, B. D. (2014). Neighborhood factors related to the likelihood of successful informal social control efforts. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42, 421–430.

Wellman, B., & Wortley, S. (1990). Different strokes from different folks: Community ties and social support. American Journal of Sociology, 96(3), 558–588.

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). The police and neighborhood safety: Broken windows. Atlantic Monthly, 127, 29–38.

Wright, E. M. (2012). The relationship between social support and intimate partner violence in neighborhood context. Crime & Delinquency. doi:10.1177/0011128712466890.

Wright, E. M., & Benson, M. L. (2010). Immigration and intimate partner violence: Exploring the immigrant paradox. Social Problems, 57(3), 480–503.

Wright, E. M., & Benson, M. L. (2011). Clarifying the effects of neighborhood disadvantage and collective efficacy on violence “behind closed doors”. Justice Quarterly, 28(5), 775–798.

Xue, Y., Leventhal, T., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Earls, F. J. (2005). Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year olds. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(5), 554–563.

Zimmerman, G. M., & Messner, S. F. (2010). Neighborhood context and the gender gap in adolescent violent crime. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 958–980.

Zimmerman, G. M., & Messner, S. F. (2011). Neighborhood context and nonlinear peer effects on adolescent violent crime. Criminology, 49(3), 873–903.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, E.M., Pinchevsky, G.M., Benson, M.L. et al. Intimate Partner Violence and Subsequent Depression: Examining the Roles of Neighborhood Supportive Mechanisms. Am J Community Psychol 56, 342–356 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9753-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9753-8