Abstract

Women experience a higher incidence of oral diseases including periodontal diseases and temporomandibular joint disease (TMD) implicating the role of estrogen signaling in disease pathology. Fluctuating levels of estrogen during childbearing age potentiates facial pain, high estrogen levels during pregnancy promote gingivitis, and low levels of estrogen during menopause predisposes the TMJ to degeneration and increases alveolar bone loss. In this review, an overview of estrogen signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo that regulate pregnancy-related gingivitis, TMJ homeostasis, and alveolar bone remodeling is provided. Deciphering the specific estrogen signaling pathways for individual oral diseases is crucial for potential new drug therapies to promote and maintain healthy tissue.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jin LJ, et al. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016;22(7):609–19.

Kessler JL. A literature review on women’s oral health across the life span. Nurs Womens Health. 2017;21(2):108–21.

Bueno CH, et al. Gender differences in temporomandibular disorders in adult populational studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45(9):720–9.

Cauley JA. Estrogen and bone health in men and women. Steroids. 2015;99(Pt A):11–5.

Chidi-Ogbolu N, Baar K. Effect of estrogen on musculoskeletal performance and injury risk. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1834.

Ohrbach R, et al. Clinical findings and pain symptoms as potential risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain. 2011;12(11 Suppl):27–45.

Manfredini D, et al. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112(4):453–62.

LeResche L. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8(3):291–305.

LeResche L, et al. Use of exogenous hormones and risk of temporomandibular disorder pain. Pain. 1997;69(1–2):153–60.

Warren MP, Fried JL. Temporomandibular disorders and hormones in women. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169(3):187–92.

Slade GD, et al. Signs and symptoms of first-onset TMD and sociodemographic predictors of its development: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain. 2013;14(12 Suppl):T20.e1-3–32.e1-3.

Slade GD, et al. Painful temporomandibular disorder: decade of discovery from OPPERA studies. J Dent Res. 2016;95(10):1084–92.

Macfarlane TV, et al. Oro-facial pain in the community: prevalence and associated impact. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30(1):52–60.

Lovgren A, et al. Temporomandibular pain and jaw dysfunction at different ages covering the lifespan—a population based study. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(4):532–40.

Maixner W, et al. Overlapping chronic pain conditions: implications for diagnosis and classification. J Pain. 2016;17(9 Suppl):T93–107.

Schiffman E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the international RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28(1):6–27.

Guarda-Nardini L, et al. Age-related differences in temporomandibular disorder diagnoses. Cranio. 2012;30(2):103–9.

Back K, et al. Relation between osteoporosis and radiographic and clinical signs of osteoarthritis/arthrosis in the temporomandibular joint: a population-based, cross-sectional study in an older Swedish population. Gerodontology. 2017;34(2):187–94.

Jagur O, et al. Relationship between radiographic changes in the temporomandibular joint and bone mineral density: a population based study. Stomatologija. 2011;13(2):42–8.

Dervis E. Oral implications of osteoporosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100(3):349–56.

Brett KM, Madans JH. Use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: estimates from a nationally representative cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(6):536–45.

Martin MD, et al. Intubation risk factors for temporomandibular joint/facial pain. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(3):109–14.

Lora VR, et al. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in postmenopausal women and relationship with pain and HRT. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30(1):e100.

Nekora-Azak A, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy among postmenopausal women and its effects on signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. Cranio. 2008;26(3):211–5.

Hatch JP, et al. Is use of exogenous estrogen associated with temporomandibular signs and symptoms? J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(3):319–26.

Mayoral VA, Espinosa IA, Montiel AJ. Association between signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and pregnancy (case control study). Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2013;26(1):3–7.

Ivković N, et al. Relationship between symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and estrogen levels in women with different menstrual status. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2018;32(2):151–8.

LeResche L, et al. Musculoskeletal orofacial pain and other signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders during pregnancy: a prospective study. J Orofac Pain. 2005;19(3):193–201.

Turner JA, et al. Targeting temporomandibular disorder pain treatment to hormonal fluctuations: a randomized clinical trial. Pain. 2011;152(9):2074–84.

Almarza AJ, et al. Preclinical animal models for temporomandibular joint tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2018;24(3):171–8.

Juran CM, Dolwick MF, McFetridge PS. Engineered microporosity: enhancing the early regenerative potential of decellularized temporomandibular joint discs. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21(3–4):829–39.

Rees L. The structure and function of the mandibular joint. Br Dent J. 1954;96(6):125–33.

Nakano T, Scott PG. Changes in the chemical composition of the bovine temporomandibular joint disc with age. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41(8–9):845–53.

Almarza AJ, et al. Biochemical analysis of the porcine temporomandibular joint disc. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44(2):124–8.

Shengyi T, Xu Y. Biomechanical properties and collagen fiber orientation of TMJ discs in dogs: part 1. Gross anatomy and collagen fiber orientation of the discs. J Craniomandib Disord Facial Oral Pain. 1991;5(1):28–34.

Minarelli AM, Del Santo JM, Liberti EA. The structure of the human temporomandibular joint disc: a scanning electron microscopy study. J Orofac Pain. 1997;11(2):95–100.

Nakano T, Scott PG. A quantitative chemical study of glycosaminoglycans in the articular disc of the bovine temporomandibular joint. Arch Oral Biol. 1989;34(9):749–57.

Detamore MS, et al. Quantitative analysis and comparative regional investigation of the extracellular matrix of the porcine temporomandibular joint disc. Matrix Biol. 2005;24(1):45–57.

Axelsson S, Holmlund A, Hjerpe A. Glycosaminoglycans in normal and osteoarthrotic human temporomandibular joint disks. Acta Odontol Scand. 1992;50(2):113–9.

Allen KD, Athanasiou KA. Tissue engineering of the TMJ disc: a review. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(5):1183–96.

Detamore MS, et al. Cell type and distribution in the porcine temporomandibular joint disc. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(2):243–8.

Wright GJ, et al. Tensile biomechanical properties of human temporomandibular joint disc: effects of direction, region and sex. J Biomech. 2016;49(16):3762–9.

Wright GJ, et al. Electrical conductivity method to determine sexual dimorphisms in human temporomandibular disc fixed charge density. Ann Biomed Eng. 2018;46(2):310–7.

Wadhwa S, Kapila S. TMJ disorders: future innovations in diagnostics and therapeutics. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(8):930–47.

Jing Y, et al. Chondrocytes directly transform into bone cells in mandibular condyle growth. J Dent Res. 2015;94(12):1668–75.

Luder HU. Age changes in the articular tissue of human mandibular condyles from adolescence to old age: a semiquantitative light microscopic study. Anat Rec. 1998;251(4):439–47.

Gepstein A, et al. Association of metalloproteinases, tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases, and proteoglycans with development, aging, and osteoarthritis processes in mouse temporomandibular joint. Histochem Cell Biol. 2003;120(1):23–32.

Silbermann M, Livne E. Age-related degenerative changes in the mouse mandibular joint. J Anat. 1979;129(Pt 3):507–20.

McDaniel JS, et al. Transcriptional regulation of proteoglycan 4 by 17beta-estradiol in immortalized baboon temporomandibular joint disc cells. Eur J Oral Sci. 2014;122(2):100–8.

Kapila S, Xie Y. Targeted induction of collagenase and stromelysin by relaxin in unprimed and beta-estradiol-primed diarthrodial joint fibrocartilaginous cells but not in synoviocytes. Lab Invest. 1998;78(8):925–38.

Naqvi T, et al. Relaxin’s induction of metalloproteinases is associated with the loss of collagen and glycosaminoglycans in synovial joint fibrocartilaginous explants. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(1):R1–11.

Hashem G, et al. Relaxin and beta-estradiol modulate targeted matrix degradation in specific synovial joint fibrocartilages: progesterone prevents matrix loss. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R98.

Talwar RM, et al. Effects of estrogen on chondrocyte proliferation and collagen synthesis in skeletally mature articular cartilage. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(4):600–9.

Cheng P, et al. Effects of estradiol on proliferation and metabolism of rabbit mandibular condylar cartilage cells in vitro. Chin Med J (Engl). 2003;116(9):1413–7.

Yasuoka T, et al. Effect of estrogen replacement on temporomandibular joint remodeling in ovariectomized rats. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58(2):189–96.

Chen J, et al. Estrogen via estrogen receptor beta partially inhibits mandibular condylar cartilage growth. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(11):1861–8.

Robinson JL, et al. Estrogen promotes mandibular condylar fibrocartilage chondrogenesis and inhibits degeneration via estrogen receptor alpha in female mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8527.

Figueroba SR, et al. Dependence of cytokine levels on the sex of experimental animals: a pilot study on the effect of oestrogen in the temporomandibular joint synovial tissues. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(11):1368–75.

Grogan SP, et al. Relevance of meniscal cell regional phenotype to tissue engineering. Connect Tissue Res. 2017;58(3–4):259–70.

Gunja NJ, Athanasiou KA. Passage and reversal effects on gene expression of bovine meniscal fibrochondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(5):R93.

Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G. Steroid hormone receptors: many actors in search of a plot. Cell. 1995;83(6):851–7.

Marino M, Galluzzo P, Ascenzi P. Estrogen signaling multiple pathways to impact gene transcription. Curr Genomics. 2006;7(8):497–508.

Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(8):1951–9.

Manolagas SC, Kousteni S. Perspective: nonreproductive sites of action of reproductive hormones. Endocrinology. 2001;142(6):2200–4.

Milam SB, et al. Sexual dimorphism in the distribution of estrogen receptors in the temporomandibular joint complex of the baboon. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64(5):527–32.

Wang W, Hayami T, Kapila S. Female hormone receptors are differentially expressed in mouse fibrocartilages. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17(5):646–54.

Yu SB, et al. The effects of age and sex on the expression of oestrogen and its receptors in rat mandibular condylar cartilages. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54(5):479–85.

Ahmad N, et al. 17beta-estradiol induces MMP-9 and MMP-13 in TMJ fibrochondrocytes via estrogen receptor alpha. J Dent Res. 2018;97(9):1023–30.

Robinson JL, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates mandibular condylar cartilage growth in male mice. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2017;20(Suppl 1):167–71.

Vinel A, et al. Respective role of membrane and nuclear estrogen receptor (ER) α in the mandible of growing mice: implications for ERα modulation. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(8):1520–31.

Kamiya Y, et al. Increased mandibular condylar growth in mice with estrogen receptor beta deficiency. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(5):1127–34.

Robinson JL, et al. Sex differences in the estrogen-dependent regulation of temporomandibular joint remodeling in altered loading. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25(4):533–43.

Ye T, et al. Differential effects of high-physiological oestrogen on the degeneration of mandibular condylar cartilage and subchondral bone. Bone. 2018;111:9–22.

Torres-Chavez KE, et al. Sexual dimorphism on cytokines expression in the temporomandibular joint: the role of gonadal steroid hormones. Inflammation. 2011;34(5):487–98.

Wang XD, et al. Estrogen aggravates iodoacetate-induced temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. J Dent Res. 2013;92(10):918–24.

Xue XT, et al. Sexual dimorphism of estrogen-sensitized synoviocytes contributes to gender difference in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Oral Dis. 2018;24(8):1503–13.

Okuda T, et al. The effect of ovariectomy on the temporomandibular joints of growing rats. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54(10):1201–10.

Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(1):76–87.

Delaruelle Z, et al. Male and female sex hormones in primary headaches. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):117.

Kim K, Wojczynska A, Lee JY. The incidence of osteoarthritic change on computed tomography of Korean temporomandibular disorder patients diagnosed by RDC/TMD; a retrospective study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74(5):337–42.

Alexiou K, Stamatakis H, Tsiklakis K. Evaluation of the severity of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritic changes related to age using cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2009;38(3):141–7.

Agerberg G, Bergenholtz A. Craniomandibular disorders in adult populations of West Bothnia, Sweden. Acta Odontol Scand. 1989;47(3):129–40.

Lindberg MK, et al. Estrogen receptor specificity for the effects of estrogen in ovariectomized mice. J Endocrinol. 2002;174(2):167–78.

Wang S, et al. Identification of α2-macroglobulin as a master inhibitor of cartilage-degrading factors that attenuates the progression of posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66(7):1843–53.

Herber CB, et al. Estrogen signaling in arcuate Kiss1 neurons suppresses a sex-dependent female circuit promoting dense strong bones. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):163.

Coogan JS, et al. Determination of sex differences of human cadaveric mandibular condyles using statistical shape and trait modeling. Bone. 2018;106:35–41.

Kim DG, et al. Sex dependent mechanical properties of the human mandibular condyle. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017;71:184–91.

Iwasaki LR, et al. TMJ energy densities in healthy men and women. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25(6):846–9.

Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809–20.

Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol. 2000;2004(34):9–21.

Figuero E, et al. Effect of pregnancy on gingival inflammation in systemically healthy women: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(5):457–73.

Ali I, et al. Oral health and oral contraceptive—is it a shadow behind broad day light? A systematic review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(11):ZE01–6.

Socransky SS, et al. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(2):134–44.

Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27(6):409–19.

Kumar PS. Sex and the subgingival microbiome: do female sex steroids affect periodontal bacteria? Periodontol 2000. 2013;61(1):103–24.

Wu M, Chen SW, Jiang SY. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015:623427.

Yang I, et al. Characterizing the subgingival microbiome of pregnant African american women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2019;48(2):140–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2018.12.003

Balan P, et al. Keystone species in pregnancy gingivitis: a snapshot of oral microbiome during pregnancy and postpartum period. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2360.

Mor G, Cardenas I. The immune system in pregnancy: a unique complexity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(6):425–33.

Kovats S. Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell Immunol. 2015;294(2):63–9.

Wu M, et al. Sex hormones enhance gingival inflammation without affecting IL-1β and TNF-α in periodontally healthy women during pregnancy. Mediat Inflamm. 2016;2016:4897890.

Bieri RA, et al. Gingival fluid cytokine expression and subgingival bacterial counts during pregnancy and postpartum: a case series. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(1):19–28.

LaMonte MJ, et al. Five-year changes in periodontal disease measures among postmenopausal females: the Buffalo Osteoperio study. J Periodontol. 2013;84(5):572–84.

Wang CJ, McCauley LK. Osteoporosis and periodontitis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2016;14(6):284–91.

Wang Y, et al. Association of serum 17beta-estradiol concentration, hormone therapy, and alveolar crest height in postmenopausal women. J Periodontol. 2015;86(4):595–605.

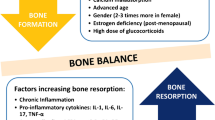

Ucer S, et al. The effects of aging and sex steroid deficiency on the murine skeleton are independent and mechanistically distinct. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(3):560–74.

Farr J, et al. Independent roles of estrogen deficiency and cellular senescence in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis: evidence in young adult mice and older humans. J Bone Miner Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3729

Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(1):30–44.

Taubman MA, Kawai T. Involvement of T-lymphocytes in periodontal disease and in direct and indirect induction of bone resorption. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12(2):125–35.

Brunetti G, et al. T cells support osteoclastogenesis in an in vitro model derived from human periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2005;76(10):1675–80.

Khosla S. Minireview: the OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology. 2001;142(12):5050–5.

Crotti T, et al. Receptor activator NF kappaB ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) protein expression in periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38(4):380–7.

Kawai T, et al. B and T lymphocytes are the primary sources of RANKL in the bone resorptive lesion of periodontal disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(3):987–98.

Hughes DE, et al. Estrogen promotes apoptosis of murine osteoclasts mediated by TGF-beta. Nat Med. 1996;2(10):1132–6.

Riggs BL. The mechanisms of estrogen regulation of bone resorption. J Clin Investig. 2000;106(10):1203–4 (Comment).

D’Amelio P, et al. Estrogen deficiency increases osteoclastogenesis up-regulating T cells activity: a key mechanism in osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;43(1):92–100.

Cenci S, et al. Estrogen deficiency induces bone loss by enhancing T-cell production of TNF-alpha. J Clin Investig. 2000;106(10):1229–37.

Ronderos M, et al. Associations of periodontal disease with femoral bone mineral density and estrogen replacement therapy: cross-sectional evaluation of US adults from NHANES III. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27(10):778–86.

Chaves JDP, et al. Sex hormone replacement therapy in periodontology—a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13059

Jönsson D, et al. Beneficial effects of hormone replacement therapy on periodontitis are vitamin D associated. J Periodontol. 2013;84(8):1048–57.

Polur I, et al. Oestrogen receptor beta mediates decreased occlusal loading induced inhibition of chondrocyte maturation in female mice. Archives of Oral Biol. 2015;60:818–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.02.007

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by startup funds from the University of Kansas and NIH NIGMS P20GM103638 (JLR), NIH Predoctoral Training Program on Pharmaceutical Aspects of Biotechnology (T32-GM008359) (PMJ), and R01DE26924 (MPI-MTY, SW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robinson, J.L., Johnson, P.M., Kister, K. et al. Estrogen signaling impacts temporomandibular joint and periodontal disease pathology. Odontology 108, 153–165 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-019-00439-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-019-00439-1