Abstract

Cluster headache (CH) is a well-defined primary headache syndrome, but cases of symptomatic headache with clinical features of CH have been previously reported. Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (IIH) is a secondary headache disorder characterized by headache and visual symptoms, without clinical, radiological or laboratory evidence of intracranial pathology. Both papilloedema and IIH-related headache are typically bilateral, however asymmetrical or even unilateral localizations are described in literature. We report the case of a previously headache-free woman who presented cluster-like headache and asymmetrical papilloedema related to IIH. In our opinion the asymmetrical presentation supports, in this case, the hypothesis of cavernous sinus involvement in the IIH-related cluster-like headache pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although cluster headache is assumed to be a primary condition, cases of symptomatic cluster-like headache have been reported, caused by various intracranial, face or cervical cord lesions or related to traumatic or surgical events [1–4, 11]. In these reported cases, symptoms were characteristic of idiopathic CH. However, the history, lacking the stereotypical periodicity of attacks, or neurological examination showing some abnormal findings, was worrisome for a secondary aetiology.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a secondary headache disorder characterized by headache and visual symptoms. Typically, IIH-related headache is persistent and bilateral; however, hemicranial or retrorbitary localizations, mimicking primary headaches are described [5]. The most common clinical finding is bilateral papilloedema, but the presentation can be asymmetric or lacking in one eye [6].

We present a case of cluster-like headache and asymmetrical papilloedema related to IIH. The possible physiopathological mechanisms are discussed.

Case report

We report a 28-year-old woman with a 4 months history of severe headache attacks, lasting 20–45 min, with a frequency between two and four attacks per day, 4–5 days a week. The pain, having pressing/tightening quality, was strictly unilateral (left side, orbital and periorbital region), radiated into the ipsilateral forehead and temple and associated with restlessness. Headache episodes were accompanied by nasal obstruction, conjunctival injection, tearing and eyelid oedema ipsilateral to the pain (Fig. 1). As at the beginning, the attacks were associated with transitory visual blurring in the left eye. The patient first consulted an ophthalmologist, who described an ipsilateral papilloedema and made a diagnosis of papillitis. A 6-week therapy with corticosteroids was prescribed, obtaining remission of visual disturbance and left papilloedema improvement, while headache episodes persisted with a mildly reduced frequency (one to two attacks/day, 4 days/week).

A month after the headache onset, the patient was hospitalized in a general neurology ward. Electroencephalogram, facial CT and standard brain MRI did not show any abnormalities. Neurological and ophthalmologic examinations were normal, except for bilateral blurring of the disc border, predominantly in the left side. Various analgesic therapies for headache episodes had been attempted unsuccessfully, while oxygen inhalation and oral zolmitriptan (5 mg) produced relief within 20 min. Thus, a diagnosis of CH was performed. As headache attacks continued and patient started having a persisting visual impairment in her left eye, she was admitted to our department. Physical examination was normal, apart from severe obesity (BMI 42.34 Kg/m2). Past medical history was unremarkable except for significant overweight since adolescence; family history was negative for headache.

Neurological and ophthalmologic examinations revealed a bilateral papilloedema, more marked in the left eye, with initial ipsilateral reduction of visual acuity (8/10). No other abnormalities were found. Visual field study showed bilateral enlargement of the blind spot and concentric constriction on the left.

Both brain and spinal cord MRI, including angio-MRI and magnetic resonance venography, were normal. Lumbar puncture, done in the left lateral decubitus, revealed an opening pressure of 480 mm H2O. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examinations, including cell count, glucose, total proteins, protein electrophoresis and Ig index were normal; viral serology and cultures were negative. Blood tests, including antinuclear antibodies, procoagulant profile, sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, cortisole, prolactin, thyroid and sexual hormones, haematic markers for Borrelia, herpes viruses and syphilis were normal.

On the hypothesis of IIH, we prescribed acetazolamide 750 mg/day and a low salt, weight reduction diet. The headache gradually decreased in frequency and intensity, and completely ceased in 4 weeks of therapy. Papilloedema disappeared and visual field normalized 3 months after acetazolamide initiation. Patient lost 15 kg in 6 months. At the follow-up (11 months) no further headache episodes occurred.

Discussion

The patient fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for cluster headache according to the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (IHCD-2) [7]. The duration of the whole headache period did not allow a distinction between episodic and chronic CH; however, the persistency of headache attacks for 4 months, exceeding the usual duration of a cluster period (ranging between 2 weeks and 3 months) [7], resembled a chronic presentation, which is common in symptomatic cases [2].

Our diagnosis of IIH was based on clinical features (papilloedema, visual impairment, visual field defects and documented increased CSF pressure) and on the absence of abnormal neuroradiological or laboratory findings, according to the IHCD-2 and Friedman criteria [7, 8].

The patient was initially misdiagnosed as papillitis, which doesn’t explain the subsequent clinical course; the following diagnosis of CH did not account for the presence of papilloedema. Although an accidental comorbidity cannot be excluded, in our opinion, the co-occurrence of asymmetrical papilloedema with ipsilateral headache, in a previously headache-free patient, and the headache improvement with acetazolamide, which is the first-line therapy for IIH [7], suggested that in this case cluster headache was caused or triggered by IIH.

The headache responsiveness to oxygen and zolmitriptan did not exclude a secondary form, since cases of symptomatic CH responsive to oxygen or triptans have been described [3, 4]. Besides, the improvement with corticosteroids was not helpful in differential diagnosis, as such a responsiveness is well known both in cluster and IIH.

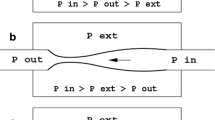

A case of cluster-like headache with bilateral papilloedema related to IIH was described by Volcy and Tepper [9]. They hypothesized that a trigeminovascular and parasympathetic pathways activation, secondary to hypothalamic dysfunction related to hypothalamic–pituitary axis alteration, or a vascular nociceptive receptor activation, secondary to cavernous sinus and tributary venous outflow obstruction, could explain the cluster-like presentation of IIH.

The hypothesis of cranial venous outflow obstruction was demonstrated in IIH by Jonston et al. [10], and attributed to compression by the elevated intracranial pressure, chronically producing focal stretching in the dural walls. Besides, it is important to note that cavernous sinus is a likely site of involvement in CH pathogenesis, since it is the crossway of the trigeminal, parasympathetic and sympathetic fibres. Thus, it is possible to speculate that in our patient, the asymmetrical onset of headache, periorbital and eyelid oedema and papilloedema correlated to a non-thrombotic left cavernous sinus hypertension.

To our knowledge, this is the second reported case of cluster-like headache related to IIH. Notably, further insights into the pathophysiology may come from CT venous angiography and CSF opening pressure after treatment. However, the present report provides further support to the hypothesis of a possible cavernous sinus involvement in the IIH-related cluster-like headache.

References

Carter DM (2004) Cluster headache mimics. Curr Pain Headache Rep 8:133–139

Geweke LO (2002) Misdiagnosis of cluster headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 6:76–82

Maggioni F, Dainese F, Mainardi F, Lisotto C, Zanchin G (2005) Cluster-like headache after surgical crystalline removal and intraocular lens implant: a case report. J Headache Pain 6:88–90

Cremer PD, Halmagyi GM, Goadsby PJ (1995) Secondary cluster headache responsive to sumatriptan. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 59:633–634

Volcy-Gómez M, Uribe CS (2004) Headaches in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A review of ten years in a Columbian hospital. Rev Neurol 39:419–423

Skau M, Brennun J, Gjerris F, Jensen R (2006) What is new about idiopathic intracranial hypertension? An updated review of mechanism and treatment Cephalalgia 26:384–389

Headache Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004) The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 24 (Suppl. 1):1–150

Friedman DI, Jacobson DM (2002) Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology 59:1492–1495

Volcy M, Tepper SJ (2006) Cluster-like headache secondary to idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Cephalalgia 26:883–886

Jonston L, Kollar C, Dunkley S, Assaad N, Parker G (2002) Cranial venous otflow obstruction in the pseudotumour syndrome: incidence, nature and relevance. J Clin neurosci 9:273–278

Giraud P, Jouanneau E, Borson-Chazot F,Lanteri-Minet M, Chazot G (2002) Cluster-like headache:literature review. J Headache Pain 3:71–78

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Testa, L., Mittino, D., Terazzi, E. et al. Cluster-like headache and idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a case report. J Headache Pain 9, 181–183 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-008-0033-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-008-0033-y