Abstract

This is the first genetic analysis comparing cultured endobacteria discovered in the tentacles of cnidarian species (Tubularia indivisa, Tubularia larynx, Corymorpha nutans, Sagartia elegans) with those found in the cerata tips of selected nudibranch species (Berghia caerulescens, Coryphella lineata, Coryphella gracilis, Janolus cristatus, Polycera faeroensis, Polycera quadrilineata, Doto coronata, Dendronotus frondosus). Shared pathogenic activities were found among other microorganisms in the Pseudoalteromonas tetraodonis group (TTX), and the Vibrio splendidus group (haemolytic, septicaemic, necrotic activity). Specific autochthonous endobacteria of extremely low similarity to their next neighbours were detected in nudibranch cerata. These organisms are regarded as new and unknown endobacteria; among them were Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea (95%), Orientia tsutsugamushi (84%), Gracilimonas tropica (96%), Balneola alkaliphia (95%), Loktanella rosea (97%). SEM micrographs provide insight into endobacterial aggregates in cnidarian tentacles and nudibranch cerata. Since certain nudibranch predators prey on cnidarian species, it is assumed that cnidarian tentacle bacteria are directly transferred to nudibranch cerata. The pathogenic endobacteria may contribute to the chemical defence of both the nudibranch and cnidarian species investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mostly colourful and gracile nudibranch species are genuine survivalists in a variety of marine habitats. Overviews of their phylogeny, diet, sophisticated defence strategies and the chemical structures of their feeding deterrents were provided by Faulkner and Ghiselin (1983), Mebs (1985), Cimino and Ghiselin (1999) and Wägele and Klussmann-Kolb (2004). McDonald and Nybakken (1996) compiled the available information on the diet of nudibranch species from all over the world. However, often the accurate feeding preferences are still unknown. Intriguing abilities of nudibranchs are disclosed when feeding on cnidarian tentacles rich in nematocycts, a usually deadly diet. Surprisingly, the cnidocysts do not harm the predators. Greenwood et al. (2004) observed that the mucus of Aeolidia papillosa inhibits the discharge of nematocysts from different species of sea anemones. A unique feature is the ability of nudibranchs to annex intact cnidarian nematocysts, transferring these unfired kleptocnides as chemical weapons into their dorsal cerata. Greenwood and Mariscal (1984) found ca. 300.000 nematocysts in the cerata of Spurilla neapolitana. Another striking feature is the incorporation of cnidarian photosynthetic zooxanthellae into the appendages of sea slugs (Marin and Ros 1991). Furthermore, chemical defence compounds from tropical sponge diets (Axinyssa aculeate) can be accumulated by the nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa. The sesquiterpenes proved to be toxic to certain shrimps (Yasman et al. 2003). Becerro et al. (2006) reported that the tropical nudibranch species Sagaminopteron nigropunctatum and S. psychedelicum feeding on the sponge Dysidea granulosa sequester polybrominated diphenyl ethers (BDEs) in their mantle material and parapodia. BDEs seem to be feeding deterrents to the pufferfish Canthigaster solandris. However, often the producers of these chemical compounds remain unclear.

Concerning a potential function of epi- or endobiotic microorganisms associated with nudibranchs, only little information is available so far. Kurahashi et al. (2008) detected a novel α-proteobacterium (Sneathiella glossodoripedis sp), collected from the foot epidermis of the nudibranch Glossodoris cincta. Conklin and Mariscal (1977) suspect the symbiotic bacteria may support the hosts’ energy retrieval. Mearns-Spragg et al. (1998) isolated bacterial epibionts from the surface of Archidoris pseudoargus which showed antimicrobial activity to terrestrial pathogens. Klussmann-Kolb and Brodie (1999) described endobiotic bacteria of unknown identity and function in the vestibular gland and in the egg masses of Dendrodoris nigra.

This paper presents the first analysis of the genetic relationships between endobacteria detected in the cerata of selected nudibranch species and those present in the tentacles of cnidarian species.

Materials and methods

Samples and preparation

Individuals of the nudibranchs Coryphella lineata, Coryphella gracilis, Berghia caerulescens, Janolus cristatus, Polycera faeroensis, Polycera quadrilineata, Doto coronata, Dendronotus frondosus, and of selected cnidarian species (Tubularia indivisa, Tubularia larynx, Corymorpha nutans and Sagartia elegans) were collected by divers during research cruises (June/July 2006–2008) from waters around the Orkney Islands. Tips of fresh cerata (nudibranchs) and tentacles (cnidaria), respectively, were clipped off and subjected to washing procedures and CTAB treatment (Schuett et al. 2007) in order to remove potentially contaminating epibiotic bacteria. Light microscopic inspection showed no bacteria attached to the surface of fresh tentacle material.

Bacterial cultures

After removing seawater, cerata and accordingly tentacle tips were placed in liquid Medium # 621 (DSMZ, German Type Culture Collection). The first set of test tubes containing one tip each was incubated under aerobic conditions for two months at 18°C. A second set containing the same sample material and medium was incubated at microaerophillic conditions (90% N2 and 10% CO2). Additionally, a third set of test tubes containing 10% modified ZoBell medium (Oppenheimer and ZobBell 1952) was prepared in the same way and incubated under aerobic conditions.

Cultures were also tested for haemolytic activity according to Smibert and Krieg (1984) by using 5% (v/v) sheep blood.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification of 16S rDNA fragments

Aliquots of 1 ml aerobic and microaerophillic mixed cultures were used for nucleic acid extraction according to Anderson and Mc Kay (1983). Primers 341fc (5′-cgc ccg ccg cgc ccc gcg ccc ggc ccg ccg ccc ccg ccc ccc tac ggg agg cag cag-3′, clamp region underlined) and 907rwob (5′-ccg tca att cct ttr agt tt-3′; Muyzer et al. 1995) were applied to PCR; parameters have been described by Schuett and Doepke (2009). Negative controls were carried out omitting template DNA; Escherichia coli J53 served as positive control. DNA quantity was checked on agarose gels.

DGGE was performed using the DCode electrophoresis system (Biorad). Preparation of polyacrylamide gels (25–55% denaturant gradient) and electrophoresis parameters (100 V, 15 h) were performed according to Muyzer et al. (1995). Bands were stained with SYBR-Gold (Molecular Probes) and excised. DNA was extracted from gel material and dissolved in 10 μl distilled water (Sambrook et al. 1989).

Re-amplification of DNA fragments from DGGE bands

The extracted DNA was re-amplified for sequencing by using the Taq DNA polymerase, but this time applying the forward primer without clamp (341f) and omitting the enhancer. PCR products were purified by using the Qiaquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) following the instructions of the manufacturer’s protocol, and eluted with 60 μl distilled water.

DNA sequencing of PCR products and comparative sequence analysis

Sequencing was carried out by Qiagen Sequencing Services/Hilden, Germany. Sequences were aligned by using the Align IR program and the advanced BLAST search program of the National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast) to find closely related sequences.

Microscopic preparation

Light microscopy

For inspection cerata/tentacles were transferred to microscopic slides. After reducing salinity (presence of distilled water enhanced the release of the bacterial aggregates), cerata/tentacles were carefully squeezed between coverslip and slide until the bacterial aggregates became sufficiently translucent for microscopic investigation.

Scanning electron microscopy

The preparation comprised the following steps: (i) Fixation of cerata/tentacle material in 4.0% glutaraldehyde, Na-K-phosphate buffer PBS (0,1 M, pH 7.0) for 2 h. (ii) Replacing seawater by ethanol in steps of 30, 50, 70, 80, 90 and 96%. (iii) Ethanol exchange by amyl acetate in steps of 25, 50, 75 and 100%. (iv) Critical point drying (Bal-Tec) in liquid CO2 at a pressure of 72.9 bar and 31.1°C. (v) Mounting of cerata/tentacle samples. (vi) Au-coating at 60 mA for 90 s (sputtering system SCD 030, Balzers). In order to allow insight to the inner location of the bacterial aggregates, cerata/tentacle tips were clipped off and the resulting cutting areas were gold coated. (vii) Samples were investigated with a SEM field emission scanning microscope (S-800, Hitachi).

Results

Genetic analysis of mixed cultures and haemolysis cultures from cnidarian and nudibranch species

Endobacteria detected in tentacle material of the cnidarians Tubularia indivisa, T. larynx, Sagartia elegans and Corymorpha nutans were also identified in cerata material of their nudibranch predators Berghia caerulescens, Coryphella lineata, C. gracilis, Dendronotus frondosus and Doto coronata. Similar bacteria were detected in cerata of the sea slugs Janolus cristatus, Polycera faeroensis and P. quadrilineata which may feed on other species of prey.

In comparison to their cnidarian preys (consult Schuett and Doepke 2009) the bacterial spectra detected in the nudibranch species investigated are relatively narrow. Up to three different bacterial species of those found in cnidaria could also be located in nudibranchs (Table. 1). Samples displayed a relationship to their next neighbours between 98 and 100% (exception Thalassobacter stenotrophicus 97%).

Shared pathogenic activities

Notably all of the nudibranch predators tested shared pathogenic endobacterial species with their cnidarian preys. Members of the group Pseudoalteromonas tetraodonis/P. elyacovii/P. haloplanktis, which may produce tetrodotoxin (TTX, Do et al. 1990) were detected in the tentacles of at least three cnidarian preys as well as in the cerata of five nudibranch predators. This also applies to the group Vibrio splendidus/V. lentus/V. tasmaniensis/V. kanaloae which is known for their haemolytic, septicaemic and necrotic activities. These two predominant pathogenic bacterial groups were discovered and described earlier by Schuett and Doepke (2009). In this context PCR-fragments used in 16SrDNA analysis were inappropriate to discriminate between the species forming these groups. Positive haemolytic activity for either bacterial group was demonstrated in selected nudibranch samples. Other endobacterial species such as Endozoicimonas elysicola (Tubularia indivisa) and Photobacterium profundum (T. indivisa, Sagartia elegans) could be spotted only in one of the nudibranch predators.

Endobacteria detected exclusively in nudibranch cerata

Besides endobacteria found in both the predators and preys, some autochthonous species could be solely located in nudibranch species: Among them were the non-pathogenic Sphingomonas baekryungensis and Bacillus arsenicus detected in Coryphella lineata, Oceanrickettia ariakensis which is suspected to be an oyster pathogenic γ–proteobacterium in Coryphella gracilis, and finally the non-pathogenic Sphingopyxis flavimaris found in Polycera quadrilineata. Sulfitobacter pontiacus, previously detected in the jellyfish Cyanea capillata, was found sheltered by Coryphella lineata and Janolus cristatus. Sulfitobacter dubius inhabited Janolus cristatus and Polycera quadrilineata. Additionally, some endobacterial species of extremely low similarity to their next neighbours could be located in the nudibranch species Coryphella lineata, C. gracilis and Janolus cristatus. Among the strange microorganisms, which are part of the autochthonous community, were Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea (95%), Orientia tsutsugamushi (84%), Gracilimonas tropica (96%), Balneola alkaliphia (95%) and Loktanella rosea (97%). These latter sequence data processed were of high quality. Due to low genetic similarity a reliable allocation of these endobacteria to known microorganisms is not feasible. Following endobacterial species found are regarded as novel organisms: Sphingopyxis baekryungensis (Yoon et al. 2005), Sphingopyxis flavimaris (Yoon and Oh 2005 , Oceanrickettia ariakensis (Sun and Wu 2004), and Loktanella rosea (Ivanova et al. 2005). Their pathogenic physiological traits are unknown.

Endobacterial aggregates in cnidarian and nudibranch species

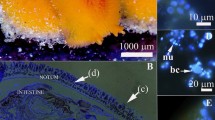

This section presents light- and scanning-micrographs of endobacterial aggregates characterized by their different sizes and derived from tentacles of the cnidarians Tubularia indivisa and Sagartia elegans as well as from cerata of the nudibranch Berghia caerulescens. Some micrographs display dividing stages of the endobacteria. Most bacterial aggregates detected in Tubularia indivisa and Sagartia elegans are covered by extremely thin and fragile envelopes. Another type of cell conglomerates does not exhibit a velum. Figure 1 shows a light microscopic image with bacterial aggregates of different sizes in the tentacle tip of Tubularia indivisa. The morphology of the aggregates and bacteria (Fig. 2) is similar to that in Sagartia elegans (Fig. 3). However, an estimation of the spherical aggregate diameters is difficult, since the sample material was strongly squeezed between slide and coverslip. During the microscopic inspection the fragile cover leads to aggregate deformation, here shown in the case of Sagartia elegans (Fig. 4).

Light microscopy provides an excellent overview of sample material, while SEM images allow the observation in detail. Tubularia indivisa harbours endobacteria in the tentacle epidermis of at least two different rod and coccoid shapes. Figure 5 displays closely packed bean-like rods (ca. 1.2 × 0.9 μm) with smooth surface which are interconnected by delicate filaments. Coccoid shaped bacterial aggregates (ca. 1.2 μm diameter) with rough surface are shown in Fig. 6. The closely packed cells are interconnected by small processes. Sagartia elegans exhibits aggregates without envelope, consisting of tightly packed rods of ca. 3 × 1 μm (Fig. 7). Other aggregates which are covered by opened envelopes (Fig. 8) harbour spherical endobacteria (ca. 1.2 μm).

Furthermore nudibranchs which prey on cnidaria, also house bacterial aggregates inside their cerata. A typical example represents Berghia caerulescens (Fig. 9). In this case as well the envelope’s appearance and the spherical shape and size of the endobacteria (ca. 1.2 μm) are similar to those detected inside the tentacles of Sagartia elegans.

Discussion

This paper provides first information on endobacteria detected inside the cerata of selected nudibranch species compared to those found in cnidarian tentacles; moreover it presents first evidence of an endomicrobial interrelationship between predators and preys.

The diet of the different nudibranch species comprises a wide spectrum of prey organisms; among them are sponges, bryozoa and cnidaria. Unfortunately, due to the dense cover and the enormous diversity of sessile invertebrates at sampling sites our divers could not definitely relate specific prey organism to individual sea slugs. According to literature data the nudibranch species we collected mostly seem to feed on cnidaria, only Janolus cristatus and both Polycera species may mainly feed on bryozoan species (McDonald and Nybakken 1996). Berghia caerulescens feeds on different cnidaria including Sagartia elegans (Ottaway 1977). Coryphella lineata (Thompson 1976), Dendronotus frondosus and Doto coronata (McDonald and Nybakken 1996) are often found to prey on Tubularia indivisa and T. larynx. Polycera faeroensis, Polycera quadrilineata and Janolus cristatus often have been detected to feed on bryozoan species (Thompson and Brown 1984; Picton and Morrow 1994), whereas Coryphella gracilis has been found to feed on Eudendrium sp. (Kinsey 2005).

Although nudibranchs show food preferences shifts are common. Cimino and Ghiselin (1999) reported diet switch in species of nudibranch orders Dendronotaceae, Arminaceae, and Aeolidiaceae from sponges to cnidaria. Indeed, diet shifts may be regarded as a smart survival strategy of sea slugs. Their flexibility in taking up a wide spectrum of diet allows for migration and colonization of new habitats. Mollo et al. (2008) recorded a Lessepsian migration of sea slugs from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean basin, an exchange that contributes significantly to Mediterranean biodiversity.

Due to the loss of shell during their evolution, sea slugs need sophisticated chemical defence mechanisms for survival; the toxins they possess are a wide choice (Gunthorpe and Cameron 1987; Greenwood et al. 2004). They could be produced de novo or taken up via prey diet. A fascinating phenomenon in nudibranchs is the ingestion of unfired nematocysts (kleptocnides) derived from cnidarian food, and their incorporation into the cerata (Greenwood 2009). Up to now in most cases it is not clear whether the toxins are produced by cnidaria or the sea slugs themselves. The results of the present paper suggest an alternative explanation: bacteria may also account for toxic activity and may be used in both sea slugs and cnidaria for chemical defence. It seems highly probable that endobacteria inhabiting cnidarian tentacles will—comparable to kleptocnides and zooxanthellae—find their way undigested through the widely branched digestive gland of nudibranchs towards the cerata.

Endobacteria detected in the tentacles of cnidarian species (Schuett et al. 2007, Schuett and Doepke 2009) show a wide scope of potentially pathogenic capability (haemolytic, necrotic, cytotoxic, septicaemic, extracellular toxic products). The present data suggest that similar pathogenic microorganisms (Pseudoalteromonas tetraodonis and Vibrio splendidus group) are also present among the endobacteria detected in the cerata of the sea slugs investigated. Positive haemolytic tests (Table 1) support this hypothesis. In this context it is unclear whether the toxins in total or fractions of these bacterial compounds may have defence functions.

The constricted bacterial spectrum detected in nudibranch cerata compared to that found in cnidarian tentacles might be caused by an extensive filter effect of the complex nudibranch gut system which ensures that only a selection of bacterial species arrive in the distant cerata.

Another remarkable aspect originates from the high numbers of virulence gene homologues detected in marine non-pathogenic bacteria (Persson et al. 2009). Those microorganisms may become pathogenic (Pallen and Wren 2007) and possibly function as additional chemical defence factor in nudibranchs and in cnidaria.

Cimino and Ghiselin (1999) stated that chemical defence is understood to be the driving force behind the evolution of nudibranchs. According this perception, the organ-like endobacterial aggregates could also be regarded as integral elements in the evolutionary development of cnidaria and their nudibranch predators.

References

Anderson DG, Mc Kay LL (1983) Simple and rapid method for isolation of large plasmid DNA from lactic streptococci. Appl Environ Microbiol 46:549–552

Becerro MA, Starmer JA, Paul VJ (2006) Chemical defenses of cryptic and aposematic gastropteris molluscs feeding on their host sponge Dysidea granulosa. J Chem Ecol 32:1491–1500

Cimino G, Ghiselin MT (1999) Chemical defense and evolutionary trends in biosynthetic capacity among dorid nudibranchs (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Opisthobranchia). Chemoecology 9:187–207

Conklin EJ, Mariscal RN (1977) Feeding behaviour, ceras structure, and nematocyst storage in the aeolid nudibranch Spurilla neapolitana. Bull Mar Sci 27:658–667

Do HK, Kogure K, Simidu U (1990) Identification of deep sea sediment bacteria which produce tetrodotoxin. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:1162–1163

Faulkner DJ, Ghiselin MT (1983) Chemical defense and evolutionary ecology of dorid nudibranchs and some other Opisthbranch gastropods. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 13:295–301

Greenwood PG (2009) Acquisition of nematocysts by cnidarian predators. Toxicon 54:1065–1070

Greenwood PG, Mariscal RN (1984) Immature nematocyst incorporation by the aeolid nudibranch Spurilla neapolitana. Mar Biol 80:35–38

Greenwood PG, Garry K, Hunter A, Jennings M (2004) Adaptable defense: nudibranch mucus inhibits nematocyst discharge and with prey type. Biol Bull 206:113–120

Gunthorpe L, Cameron AM (1987) Bioactive properties of extracts from Australian dorid nudibranchs. Mar Biol 94:39–43

Ivanova EP, Zhukova NV, Gorshkova NM, Sergeev AF, Mikhailov VV, Bowman JP (2005) Loktanella agita sp. nov. and Loktanella rosea sp. nov., from the north-west Pacific Ocean. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55:2203–2207

Kinsey EF (2005) Nematocyst complements of nudibranchs in the genus Flabellina in the Gulf of Maine and the effect of diet manipulations on the cnidom of Flabellina verrucosa. Mar Biol 147:1313–1321

Klussmann-Kolb A, Brodie GD (1999) Internal storage and production of symbiotic bacteria in the reproductive system of a tropical marine gastropod. Mar Biol 133:443–447

Kurahashi M, Fukunaga Y, Harayama S, Yokota A (2008) Sneathiella glossodoripedis sp. nov., a marine alpha-proteabacterium isolated from the nudibranch Glossodoris cincta and proposal of Sneathiellales ord. nov. and Sneathiellaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58:548–552

Marin A, Ros J (1991) Presence of intracellular zooxanthellae Mediterranean nudibranchs. J Mol Stud 57:87–101

McDonald G, Nybakken JW (1996) A list of the worldwide food habits of nudibranchs. Online article: http://people.ucsc.edu/~mcduck/nudifood.htm

Mearns-Spragg A, Bregu M, Boyd KG, Burgess JG (1998) Cross species induction and enhancement of antimicrobial activity produced by epibiotic bacteria from marine algae and invertebrates, after exposure to terrestrial bacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol 27(3):142–146

Mebs D (1985) Chemical defense of a dorid nudibranch glossodoris quadricolor from the Red Sea. J Chem Ecol 11:713–716

Mollo E, Gavagnin M, Carbone M, Castellucio F, Pozone F, Roussis V, Templado J, Ghiselin MT, Cimino G (2008) Factors promoting marine invasions: a chemoecological approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 25:4582–4586

Muyzer G, Hottenträger S, Teske A, Wawer C (1995) Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA. A new molecular approach to analyze the genetic diversity of mixed microbial communities. Mol Microb Ecol Manual 3(44):1–22

Oppenheimer CH, ZobBell CE (1952) The growth and viability of sixty-three species of marine bacteria as influenced by hydrostatic pressure. J Mar Res 11:10–18

Ottaway JR (1977) Predators of sea anemones. NZETC. Tuatara 22(3):213–221

Pallen MJ, Wren BW (2007) Bacterial pathogenomics. Nature 440:835–842

Persson OP, Pinhassi J, Riemann L, Marklund B-I, Nordmark S, Gonzalez JM, Hagström Å (2009) High abundance of virulence gene homologues in marine bacteria. Env Microbiol 11:1348–1357

Picton BE, Morrow CC (1994) A field Guide to the nudibranchs of the British Isles. Immel Publishing Ltd, London

Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York

Schuett C, Doepke H (2009) Endobiotic bacteria and their pathogen potential in cnidarian tentacles. Helgol Mar Res. doi:10.1007/s10152-009-0179-2

Schuett C, Doepke H, Grathoff A, Gedde M (2007) Bacterial aggregates in the tentacles of the sea anemone Metridium senile. Helgol Mar Res 61:211–216

Smibert RM, Krieg NR (1984) General characterization. In: Gerhardt P, Murray RGE, Costilow RN, Nester EW, Wood WA, Krieg NR, Phillips GB (eds) Manual of methods for general bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC

Thompson TE (1976) Biology of opistobranch molluscs. The Ray Society 1:1–206

Thompson TE, Brown GH (1984) Biology of opistobranch molluscs. The Ray Society 2:1–229

Wägele H, Klussmann-Kolb A (2004) Opisthobranchia (Mollusca, Gastropoda)–more than just slimy slugs. Shell reduction and its implications on defence and foraging. Front Zool 2:1–18

Sun JF, Wu XZ (2004) The histology ultrastructure and morphogenesis of a rickettia-like organism causes diseases in the oyster Crassostrea arikensis Gould. J Invertebr Pathol 86:77–86

Yasman Y, Edrada RA, Wray V, Proksch P (2003) New 9-thiocyanatopupukeanane sesquiterpenes from the nudibranch Phyllidia varicose and its sponge-prey Axinyssa aculeata. J Nat Prod 66:1512–1514

Yoon J-H, Oh T-K (2005) Sphingopyxis flavimaris sp. nov., isolated from sea water of the Yellow Sea in Korea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55:369–373

Yoon J-H, Lee C-H, Yeo S-H, Oh T-K (2005) Sphingopyxis baekryungensis sp. nov. an orange-pigmented bacterium isolated from sea-water of the Yellow-Sea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55:1223–1227

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the divers who provided excellent fresh cnidarian and nudibranch sample material from difficult Atlantic locations. Thanks are due to the crew of RV Heincke for their skilful engagement in difficult Scottish waters.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Communicated by H.-D. Franke.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doepke, H., Herrmann, K. & Schuett, C. Endobacteria in the tentacles of selected cnidarian species and in the cerata of their nudibranch predators. Helgol Mar Res 66, 43–50 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-011-0245-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-011-0245-4