Abstract

Phytoplankton microscopic enumerations and HPLC analyses of their pigments were performed weekly for a complete year at a coastal station in the English Channel. The taxonomic composition of the phytoplankton community was assessed using the HPLC results combined with the mathematical tool CHEMTAX in two different ways. Firstly, without using the species level taxonomic information obtained at the microscopic level (blind analyses), and secondly by including the information from the microscopic taxonomic analysis (directed analyses). The results indicate that, due to the particular pigment composition of some species (for example, the dinoflagellate, Karenia mikimotoi and the haptophyte, Phaeocystis pouchetii), a blind analysis would result in very significant errors in the taxonomic determination of the bloom events at this station. Major blooms of Karenia mikimotoi and P. pouchetii were mistaken for blooms of diatoms on the basis of a blind HPLC-CHEMTAX analysis. Only with the information from the microscopic observations was it possible to obtain an accurate representation of the phytoplankton community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the early development of the HPLC technique, marker pigments have been employed to estimate or characterise the taxonomic composition of phytoplankton assemblages. However, recently the development of a mathematical program (CHEMTAX) has allowed a relatively accurate determination of the contribution to the total chlorophyll a (Chl a; or biomass) of each phytoplankton taxon (Mackey et al. 1996; Descy et al. 2000). The combination of HPLC and CHEMTAX has been proposed as a powerful tool for studying phytoplankton communities (Riegman and Kraay 2001).

Nevertheless, as with HPLC analysis alone, the use of the HPLC-CHEMTAX combination still requires some previous knowledge of the group-specific marker pigments and the marker pigment to Chl a ratio for each phytoplankton group. Some pigments are generally associated with the major phytoplankton groups, for example peridinin with dinoflagellates, and fucoxanthin with diatoms, and such relationships are collated in the initial marker pigment-Chl a matrix used by CHEMTAX. Particular attention has been paid to the issue of variations in the marker pigment-Chl a ratio due to factors such as nutrient status and light (Mackey et al. 1996; Descy et al. 2000; Higgins and Mackey 2000; Schlueter et al. 2000). However, it has also been pointed out that specific differences in the marker pigment composition within the same phytoplankton group affect the accuracy of the analysis (Landry et al. 2000).

In this work, we show how a completely blind analysis using such an approach, without any knowledge of the phytoplankton population at the species level, can result in serious errors in the pigment-derived taxonomic composition of the phytoplankton.

Methods

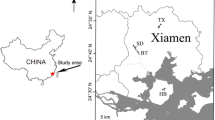

Subsurface samples (10 m) were collected weekly between July 1997 and June 1998 from coastal station L4 (50°15′N, 4°13′W) located about 10 km off Plymouth in the English Channel (http://www.pml.ac.uk/L4). Samples were collected for microscopic enumeration of phytoplankton and for the analysis of phytoplankton pigments using HPLC. Resulting HPLC data were used to run CHEMTAX in two modes: (1) with a general initial matrix, using marker pigment-Chl a ratios obtained from the literature (blind analyses), and (2) using the information from the microscopic analyses to determine the characteristics of the initial marker pigment-Chl a matrix for each period (directed analyses).

For microplankton species identification and carbon estimation, samples were preserved with 1% final concentration Lugol’s iodine solution, and a separate sample was fixed with neutral formalin for determination of coccolithophorids (Holligan and Harbour 1977). Subsamples of 100 ml volume were settled (Utermöhl) and counted using an inverted microscope. Phytoplankton carbon biomass was estimated from cell volume according to Strathmann (1967).

For HPLC analyses,1 l was filtered through Whatman GF/F filters and frozen at −80°C prior to HPLC analysis. Marker pigments were analysed by HPLC following Barlow et al. (1997) and Gibb et al. (2000). The marker pigments were identified through comparison with the retention and spectral properties of standards (UKI Denmark, Sigma). The following pigments were employed to determine taxon-specific contributions to Chl a: Chl c 3 , Chl c 1 +c 2 , peridinin, 19′-butanoyloxyfucoxanthin, fucoxanthin, 19′-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, diadinoxanthin, alloxanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein, Chl b and Chl a.

The contribution of each major phytoplankton taxon to Chl a was calculated using the CHEMTAX program developed by Mackey et al. (1996).

CHEMTAX requires the use of input matrices with approximate marker pigment-Chl a ratios to calculate the final marker pigment-Chl a ratio and the group-specific Chl a concentration. For the blind analyses, the initial matrix is presented in Table 1.

In the directed analyses, we used different input matrices for the periods when species with particular pigments dominated their taxonomic group (Schlueter et al. 2000, see Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 for details).

Results and discussion

The weaknesses of Chl a as a biomass predictor have often been emphasised (see review of C:Chl a ratios by Peterson and Festa 1984). The first interesting result from our study is that it supports this view that Chl a is a poor indicator of biomass. The spring and summer blooms have approximately the same magnitude in terms of Chl a, whereas the carbon biomass of the summer dinoflagellate bloom is about six times that of the spring haptophytes and diatoms (Fig. 1A, B). This could be due to the fact that, during the strongly stratified summer period, the dinoflagellates are exposed to a much higher light intensity than diatoms and haptophytes are during the mixed conditions of the spring: therefore the amount of Chl a required to maintain the same biomass is lower (Moal et al. 1987; Brown et al. 1993). It is also known that dinoflagellates generally have a higher density than diatoms (Moal et al. 1987).

Seasonal variation in phytoplankton biomass from microscopic analysis. B Seasonal variation in Chl a concentration measured by HPLC. C Seasonal variation in the concentration of marker pigments. 19-hexa 19′-Hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin; 19-but 19′-butanoyloxyfucoxanthin. D CHEMTAX results from the blind analysis: Group-specific contribution to the total Chl a. E CHEMTAX results from the directed analysis: Group specific contribution to the total Chl a

The second important result from our analyses is that the HPLC-CHEMTAX blind analyses produced a distorted picture of the seasonal phytoplankton succession pattern. Both the summer bloom of dinoflagellates and the spring bloom of haptophytes are interpreted as being composed of diatoms due to the high concentration of fucoxanthin (Fig. 1C, D). In both cases, the presence of Chl c 3 suggests the presence of a different population in the water, but using the common ratios used for each group (Table 1) it was not possible to resolve the problem. It was necessary to go to the species level in the microscopic analysis to understand the composition of the phytoplankton population and produce an adequate input matrix for CHEMTAX (Fig. 1E).

Both the dinoflagellate Karenia mikimotoi (formerly Gyrodinium aureolum) and the haptophyte Phaeocystis pouchetii have an unusual marker pigment composition for their groups, as they both contain fucoxanthin. However, both are common bloom-forming species in the North Sea and North Atlantic shelf regions, with important roles in the dimethylsulphide (DMS) cycle (P. pouchetii; Turner et al. 1996) or are involved in fish mortality and inhibition of zooplankton fecundity (K. mikimotoi; Gill and Harris 1987; Partensky et al. 1989). Landry et al. (2000) reported similar difficulties in estimating the contribution of dinoflagellates when using CHEMTAX in the equatorial Pacific, and pointed out the absence of peridinin in some genera as a possible cause.

With the directed analysis, the phytoplankton bloom composition was correctly represented. However, important differences between microscopic counting and HPLC estimates during the winter period remain (Fig. 2A, B). This could be due to differences in the volume sampled (100 ml for microscope and 1 l for HPLC), with large but scarce cells such as diatoms being perhaps underestimated by the 100 ml samples. However, this result could also be a consequence of our lack of information about the pigment composition of usually unidentified small flagellates.

For community description purposes, algal categories have been defined by their pigment content (Wright and Van den Enden 2000). However, because of the functional differences between taxa, this approach cannot be taken when considering their role in the ecosystem or in biogeochemical cycles (e.g. toxicity and DMS production).

Our results indicate that a blind analysis of the HPLC data, without taxonomic information from microscopic counting, would have resulted in a misinterpretation of the composition of two of the three main annual blooms, ignoring two species with important consequences in terms of biogeochemical fluxes and impact on the planktonic community.

Those problems are not exclusive to the CHEMTAX-HPLC combination, but are general to any approach using HPLC pigment data to extrapolate phytoplankton composition without adequate previous knowledge of the population.

The CHEMTAX manual already states that “The CHEMTAX program assumes that all members of a given algal class have the same “typical” set of pigment ratios. Care should therefore be taken to ensure that the pigment ratios used are from dominant species of the given algal class or that the species chosen is indeed representative of the remainder of the algal class for the particular group of samples under study. In other words, an a priori knowledge of the community under study is extremely useful in determining the range of algal classes likely to be found...”.

Our results indicate that a priori knowledge is not only extremely useful, but essential, avoid significant mistakes and misinterpretation with potentially important consequences. This knowledge may even need to be at the species level (Schlueter et al. 2000).

It is a logical step to discard a laborious procedure in favour of new, easier techniques, and there is a natural trend to use HPLC results, either alone (e.g. Casotti et al. 2000; Belviso et al. 2001; Smith and Asper 2001) or in combination with CHEMTAX (e.g. Wright and Van den Enden 2000; Gibb et al. 2001; Riegman and Kraay 2001) without supporting microscopic cell identification. However, our results indicate that, even with this level of knowledge about pigment specificity, this can be a risky approach leading to significant errors: additional microscopic identification is still necessary.

CHEMTAX remains a very useful tool that addresses the shortcomings of the multiple regression approach when estimating the contribution of different groups to the total biomass. Furthermore, with a good knowledge of the specific pigment composition of certain species, CHEMTAX can be used to determine the concentration of individual species (Oernolfsdottir et al. 2003). Nevertheless, CHEMTAX should not be taken as a shortcut, and the a priori knowledge indicated in the manual is necessary.

References

Barlow RG, Cummings DG, Gibb S (1997) Improved resolution of mono and divinyl chlorophylls a and b and zeaxanthin and lutein in phytoplankton extracts using reverse phase C-8 HPLC. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 161:303–307

Belviso S, Claustre H, Marty JC (2001) Evaluation of the utility of chemotaxonomic pigments as a surrogate for particulate DMSP. Limnol Oceanogr 46:989–995

Brown MR, Dunstan GA, Jeffrey SW, Volkman JK, Barrett SM, LeRoi JM (1993) The influence of irradiance on the biochemical composition of the prymensiophyte Isochrysis sp. (clone T-iso). J Phycol 29:601–612

Casotti R, Brunet C, Aronne B, D’Alcala R (2000) Mesoscale features of phytoplankton and planktonic bacteria in a coastal area as induced by external water masses. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 195:15–27

Descy JP, Higgins HW, Mackey DJ, Hurley JP, Frost TM (2000) Pigment ratios and phytoplankton assessment in northern Wisconsin lakes. J Phycol 36:274–286

Gibb SW, Barlow RG, Cummings DG, Rees NW, Trees CC, Holligan P, Suggett D (2000) Surface phytoplankton pigment distributions in the Atlantic Ocean: an assessment of basin scale variability between 50°N and 50°S. Prog Oceanogr 45:339–368

Gill CW, Harris RP (1987) Behavioural responses of the copepods Calanus helgolandicus and Temora longicornis to dinoflagellates diets. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 67:785–801

Higgins HW, Mackey DJ (2000) Algal class abundances, estimated from chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments, in the western equatorial Pacific under El Nino and non-El Nino conditions. Deep-Sea Res I 8:1461–1483

Holligan PM, Harbour DS (1977) The vertical distribution and succession of phytoplankton in the western English Channel in 1975 and 1976. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 57:1075–1093

Jeffrey SW, Wright SW (1994) Photosynthetic pigments in the Haptophyta. In: Green JC, Leadbeater BSC (eds) The haptophyte algae. Systematic Association, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 111–132

Johnsen G, Sakshaug E (1993) Bio-optical characteristics and photoadaptive responses in toxic and bloom-forming dinoflagellates Gyrodinium aureolum, Gymnodinium galatheanum, and two strains of Prorocentrum minimum. J Phycol 29:627–642

Landry MR, Ondrusek ME, Tanner SJ, Brown SL, Constantinou J, Bidigare RR, Coale KH, Fitzwater S (2000) Biological response to iron fertilization in the eastern equatorial Pacific (IronEx II). Microplankton community abundances and biomass. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 201:27–42

Mackey MD, Mackey DJ, Higgins HW, Wright SW (1996) CHEMTAX—a program for estimating class abundance from chemical markers: application to HPLC measurements of phytoplankton. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 144:265–283

Moal J, Martin-Jezequel V, Harris RP, Samain JF, Poulet SA (1987) Interspecific and intraspecific variability of the chemical composition of marine phytoplankton. Oceanol Acta 10:339–346

Oernolfsdottir EB, Pinckney JL, Tester PA (2003) Quantification of the relative abundance of the toxic dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis (Dinophyta), using unique photopigments. J Phycol 39:449–457

Partensky F, Le Botterff J, Verbist JF (1989) Does the fish-killing dinoflagellate Gymnodinium cf. nagasakiense produce cytotoxins? J Mar Biol Assoc UK 69:501–509

Peterson DH, Festa JF (1984) Numerical simulation of phytoplankton productivity in partially mixed estuaries. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 19:563–589

Riegman R, Kraay GW (2001) Phytoplankton community structure derived from HPLC analysis of pigments in the Faroe-Shetland Channel during summer 1999: the distribution of taxonomic groups in relation to physical/chemical conditions in the photic zone. J Plankton Res 23:191–205

Schlueter L, Moehlenberg F, Havskum H, Larsen S (2000) The use of phytoplankton pigments for identifying and quantifying phytoplankton groups in coastal areas: Testing the influence of light and nutrients on pigment/chlorophyll a ratios. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 192:49–63

Smith WO Jr, Asper VL (2001) The influence of phytoplankton assemblage composition on biogeochemical characteristics and cycles in the Southern Ross Sea, Antarctica. Deep Sea Res I 48:137–161

Strathmann RR (1967) Estimating the organic carbon content of phytoplankton from cell volume or plasma volume. Limnol Oceanogr 12:411–418

Turner SM, Malin G, Nightingale PD, Liss PS (1996) Seasonal variation of dimethyl sulphide in the North Sea and an assessment of fluxes to the atmosphere. Mar Chem 54:245–262

Wright SW, Jeffrey SW (1997) High-resolution HPLC system for chlorophylls and carotenoids of marine phytoplankton. In: Jeffrey SW, Mantoura RFC, Wright SW (eds) Phytoplankton pigments in oceanography. UNESCO, pp 327–360

Wright SW, Van den Enden RL (2000) Phytoplankton community structure and stocks in the East Antarctic marginal ice zone determined by Chemtax analysis of HPLC pigment signatures. Deep Sea Res II 47:2363–2400

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to S.W. Gibb for his helpful comments on previous versions of the manuscript. This research was supported by the NERC Marine Productivity thematic programme GST/02/2760. B. Meyer was supported by an EU grant (TMR, MAS3-CT96-5032). Thanks are due to the captains and crew of the RV Squilla and RV Sepia for collecting the samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H.-D. Franke

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Irigoien, X., Meyer, B., Harris, R. et al. Using HPLC pigment analysis to investigate phytoplankton taxonomy: the importance of knowing your species. Helgol Mar Res 58, 77–82 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-004-0171-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-004-0171-9